Ikebana

Ikebana (生け花, "arranging flowers") is the Japanese art of flower arrangement, also known as kadō (華道, the "way of flowers"). The tradition dates back to the 7th century when floral offerings were made at altars. Later they were placed in the tokonoma alcove of a home. Ikebana reached its first zenith in the 16th century under the influence of Buddhist teamasters and has grown over the centuries, with over 1000 different schools in Japan and abroad. The best known schools are Ikenobo, Ohara-ryū, and Sōgetsu-ryū.

Kadō is counted as one of the three classical Japanese arts of refinement, along with kōdō for incense appreciation and chadō for tea and the tea ceremony.

Etymology

"Ikebana" is from the Japanese ikeru (生ける, "keep alive, arrange flowers, living") and hana (花, "flower"). Possible translations include "giving life to flowers" and "arranging flowers".[1]

History

Recent historical research now indicates that the practice of tatebana ("standing flowers"),[2] derived from a combination of belief systems including Buddhist and Shinto Yorishiro, is most likely the origin of the Japanese practice of ikebana that we know today. During ancient times, offering flowers on the altar in honor of Buddha was part of worship, called mitsu-gusoku.

Ikebana evolved from the Buddhist practice of flower offerings combined with the Shinto Yorishiro belief of attracting kami by using evergreen materials. Together they form the basis for the original purely Japanese derivation of the practice of ikebana. The first systematized classical styles of ikebana, including rikka, started in the middle of the fifteenth century; the first students and teachers of ikebana were Ikenobo Buddhist priests and members of the Buddhist community. As time passed, other schools emerged, styles changed, and ikebana became a custom among the whole of Japanese society.[3]

Schools

Hundreds of schools and styles have developed throughout the centuries. Amongst the most notable are:

- Ikenobō, which goes back to the Heian period, is considered the oldest school. This school marks its beginnings from the construction of the Chōhō-ji in Kyoto, the second oldest Buddhist temple in Japan. It was built in 587 by Prince Shotoku, who had camped near a lake in what is now central Kyoto. During the night he dreamed that Nyoirin Kannon appeared to him saying, “With this amulet I have given you, I have protected many generations, but now I wish to remain in this place. You must build a six sided temple and enshrine me within this temple. Many people will come here and be healed.” So Prince Shotoku built the Chōhō-ji temple, now referred to as the Rokkakudo Temple (six sided) and enshrined Nyoirin Kannon within it. In subsequent years an official state emissary, Ono, brought the practice of placing Buddhist flowers on an altar from China, became a priest at the Chōhō-ji, and spent the rest of his days practicing flower arranging. The original priests of the temple lived by the side of a lake, for which the Japanese word is 'Ike' "池", and the word 'Bō' "坊", meaning priest, connected by the possessive particle 'no' ”の” gives the meaning, 'priest of the lake', 'Ikenobō' "池坊". The name Ikenobō granted by the Emperor became attached to the priests there who specialized in altar arrangements. This school is the only one that does not have the ending -ryū in its name, as it is considered the original school.

- Saga Go-ryū school dates back to Emperor Saga, who reigned from 809–823 CE. The main seat of this school is at the Daikaku-ji in Kyoto, which is the former residence of the emperor. The school has five principal styles, namely Seika, Heika, Moribana, Shogonka and the newer style Shinshoka.

- Senkei-ryū was founded around 1669 by Senkei Tomiharunoki.

- Yōshin Goryū developed during the Edo period.

- Mishō-ryū began in the beginning of the 19th century. It was founded by Ippo Mishōsai (1761–1824) in Osaka.

- Ohara-ryū was founded in 1895 by Ohara Unshin. Japan was opening towards the West at that time, so new styles were developed.

- Sōgetsu-ryū was founded in 1927 by Teshigahara Sofu. He continued the development of the popular flat-dish Moribana style into the freestyle Jiyuka.

- Banmi Shofu-ryū was founded in 1962 by Bessie "Yoneko Banmi" Fooks.

- Kaden-ryū was founded by Kikuto Sakagawa in 1987 and is based on the Ikenobo school.

Evolution of styles

Patterns and styles evolved, and by the late 15th century arrangements were common enough to be appreciated by ordinary people and not only by the imperial family and its retainers.

Ikebana in the beginning was very simple, constructed from only a very few stems of flowers and evergreen branches. This first form of ikebana is called kuge (供華).

Styles of ikebana changed in the late 15th century and transformed into an art form with fixed instructions. Books were written about it, "Sedensho" being the oldest one, covering the years 1443 to 1536. ikebana became a major part of traditional festivals, and exhibitions were occasionally held.

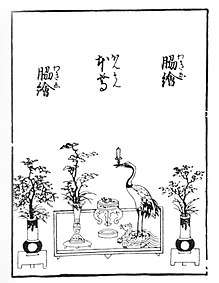

The first styles were characterized by a tall, upright central stem accompanied by two shorter stems. During the Momoyama period, 1560–1600, splendid castles were constructed. Noblemen and royal retainers made large decorative rikka floral arrangements that were considered the most appropriate decoration for castles.

The Rikka (standing flowers) style was developed as a Buddhist expression of the beauty of landscapes in nature. Key to this style are nine branches that represent elements of nature:[4]

When the tea ceremony emerged, another style was introduced for tea ceremony rooms called chabana. This style is the opposite of the Momoyama style and emphasizes rustic simplicity. The simplicity of chabana in turn helped create the nageirebana or “thrown-in” style.

Nageirebana is a non-structured design which led to the development of the seika or shoka style. It is characterized by a tight bundle of stems that form a triangular three-branched asymmetrical arrangement that was considered classic. It is also known in the shortform nageire.

Seika or Shōka style consists of only three main parts, known in some schools as ten (heaven), chi (earth), and jin (human). It is a simple style that is designed to show the beauty and uniqueness of the plant itself. Formalization of the nageire style for use in the Japanese alcove resulted in the formal shoka style.

Jiyūka is a free creative design. It is not confined to flowers; every material can be used.

20th century styles

In the 20th century, with the advent of modernism, the three schools of ikebana partially gave way to what is commonly known in Japan as Free Style.

- Moribana upright style is considered the most basic structure in ikebana. Moribana literally means “piled-up flowers” that are arranged in a shallow vase or suiban, compote vessel, or basket. Flowers are secured on kenzan or needlepoint holders, also known as metal frogs.

- Moribana slanting style is a reversed arranging style that can be used depending on the placement of the display or shapes of the branches. Branches that look beautiful when slanted are mostly chosen for this arrangement. This style gives a softer impression than the upright style.

- Nageire upright style is arranged in a narrow-mouthed, tall container without using kenzan or needlepoint holders. Nageire literally means "thrown in". This is a simple arrangement that can contain just one flower and does not use frogs to hold the flower(s).

- Nageire slanted style presents a gentle touch and flexibility. It is ideal for beginners.

- Nageire cascading style arrangements have the main stem hanging lower than the rim of the vase. A flexible material will create beautiful lines balancing with flowers.

Theory

More than simply putting flowers in a container, ikebana is a disciplined art form in which nature and humanity are brought together. Contrary to the idea of a particolored or multicolored arrangement of blossoms, ikebana often emphasizes other areas of the plant, such as its stems and leaves, and puts emphasis on shape, line, and form. Though ikebana is an expression of creativity, certain rules govern its form. The artist's intention behind each arrangement is shown through a piece's color combinations, natural shapes, graceful lines, and the implied meaning of the arrangement.

Another common but not exclusive aspect present in ikebana is its employment of minimalism. Some arrangements may consist of only a minimal number of blooms interspersed among stalks and leaves. The structure of some Japanese flower arrangements is based on a scalene triangle delineated by three main points, usually twigs, considered in some schools to symbolize heaven, earth, and man, or sun, moon, and earth. Use of these terms is limited to certain schools and is not customary in more traditional schools. A notable exception is the traditional rikka form, which follows other precepts. The container can be a key element of the composition, and various styles of pottery may be used in their construction. In some schools the container is only regarded as a vessel to hold water and should be subordinate to the arrangement.

Spiritual aspects

The spiritual aspect of ikebana is considered very important to its practitioners. Some practitioners feel silence is needed while making ikebana while others feel this is not necessary. It is a time to appreciate things in nature that people often overlook because of their busy lives. One becomes more patient and tolerant of differences, not only in nature, but also in general. Ikebana can inspire one to identify with beauty in all art forms. This is also the time when one feels closeness to nature, which provides relaxation for the mind, body, and soul.

Culture

Ikebana is shown on television and taught in schools. An example of a television show that involves ikebana is Seikei Bijin (Artificial Beauty). The story incorporates the importance of natural beauty. It was also mentioned in We Love Katamari for PS2.

International organizations

The oldest international organization, Ikebana International, was founded in 1956.[5]

Noted Japanese persons who practiced it as Junichi Kakizaki, Mokichi Okada, and Yuki Tsuji. Tsuji was at a March 2015 TEDx in Shimizu, Shizuoka where he elaborated on the relationship of ikebana to beauty.[6]

The Hollywood actress Marcia Gay Harden is a practitioner and started when she was living in Japan as a child.[7] She has published a book about it with her works.[8]

Gallery

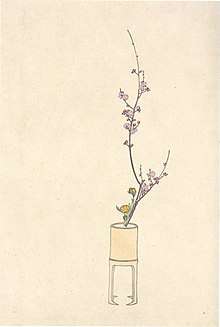

Nageire from the Banmi Shofu-ryū school

Nageire from the Banmi Shofu-ryū school Upright Moribana

Upright Moribana

See also

- Culture of Japan

- Higashiyama period

- Iemoto

- Wabi-sabi

- Hanakotoba

- Language of flowers

- Plant symbolism

- Birth flower

References

- ↑ The Modern Reader's Japanese-English Character Dictionary, Charles E. Tuttle Company, ISBN 0-8048-0408-7

- ↑ "tatebana – Japanese art style". Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ Kubo, keiko (2013). "introduction". Keiko's Ikebana: A Contemporary Approach to the Traditional Japanese Art of Flower Arranging. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462906000. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ↑ "ikebana-flowers.com". Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ "Ikebana International". Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jLwwCeBsNkE

- ↑ http://www.marthastewart.com/268653/ikebana

- ↑ Marcia Gay Harden. The Seasons of My Mother: A Memoir of Love, Family, and Flowers. Atria Books. 2018. ISBN 978-1501135705

Further reading

- Ember, M., & Ember, C. r. (2001). Countries and their Cultures. New York Pearson Education, Inc. Retrieved July 30, 2008, from NetLibrary (UMUC Database) .

- Fairchild, C. (2006). "Keiko's Ikebana: A Contemporary Approach to the Traditional Japanese Art of Flower Arranging." Library Journal, 131(1), 111–113. Retrieved July 30, 2008 from Academic Search Premiere (UMUC Database) (AN 21303368).

- Leaman, O. (2001). Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy. London: New York Taylor & Francis Routledge. Retrieved July 30, 2008 from NetLibrary (UMUC Database).

- Okakura Kakuzo, 'Flowers' in The Illustrated Book of Tea (Okakura's classic illustrated with 17th–19th century ukiyo-e woodblock prints). Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. 2012. ASIN: B009033C6M

- Evi Zamperini Pucci, Japanese Flower Arranging, Orbis Book, London, 1973 (introduction by Georgie Davidson).

- Flower Arrangement: The Ikebana Way. Dr. William C. Steere ed., Shufunotomo Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan, 1962

- The Art of Arranging Flowers. Shozo Sato, Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, undated. Library of Congress Number 65-20323

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ikebana. |

| Look up ikebana in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |