Japanese currency

Japanese currency has a history covering the period from the 8th century to the present. After the traditional usage of rice as currency medium, Japan's currency was characterized by an early adoption of currency systems and designs from China before developing a separate system of its own.

History

Commodity money

Before the advent of the 7-8th century CE, Japan used commodity money for its exchanges. It generally consisted of material that was compact, easily transportable and had a widely recognized value. Commodity money was a great improvement over simple barter, in which commodities were simply exchanged against others. Ideally, commodity money had to be widely accepted, easily portable and storable, and easily combined and divided in order to correspond to different values. The main items of commodity money in Japan were arrowheads, rice grains and gold powder, as well as hemp cloth.[1]

This contrasted somewhat with countries like China, where one of the most important item of commodity money came from the Southern seas: shells.[1] Since then however, the shell has become a symbol for money in many Chinese and Japanese ideograms.[1]

Kōchōsen currency system (8-10th century)

Embassy to the Tang court (630 CE)

Japan's first formal currency system was the Kōchōsen (Japanese: 皇朝銭, "Imperial currency"). It was exemplified by the adoption of Japan's first official coin type, the Wadōkaichin.[2] It was first minted in 708 CE on order of Empress Genmei, Japan's 43rd Imperial ruler.[2] "Wadōkaichin" is the reading of the four characters printed on the coin, and is thought to be composed of the era name Wadō (和銅, "Japanese copper"), which could alternatively mean "happiness", and "Kaichin", thought to be related to "Currency".[1] The pronunciation of "Kaichin" also sounds similar to "happiness" in Chinese "开心". This coinage was inspired by the Tang coinage (唐銭) named Kaigentsūhō (Chinese: 開元通宝, Kai Yuan Tong Bao), first minted in Chang'an in 621 CE.[1] The Wadokaichin had the same specifications as the Chinese coin, with a diameter of 2.4 cm and a weight of 3.75g.[1] The main items of commodity money in Japan were arrowheads, rice grains, and gold powder, as well as hemp cloth.[1] This contrasted somewhat with countries like China, where one of the important items of commodity money came from the Southern seas: shells.[1] Since then however, the shell has commonly become a symbol for money in many Japanese ideograms.[1]

Chinese shell money from the 16th to 8th centuries BCE. They were widely accepted, easily portable and storable, they were also easily combined and divided in order to correspond with different values.

Chinese shell money from the 16th to 8th centuries BCE. They were widely accepted, easily portable and storable, they were also easily combined and divided in order to correspond with different values. Japanese commodity money before the 8th century, including: arrowheads, rice grains, and gold powder. Now in the Japanese Currency Museum.

Japanese commodity money before the 8th century, including: arrowheads, rice grains, and gold powder. Now in the Japanese Currency Museum. The Japanese embassy to the Tang court.

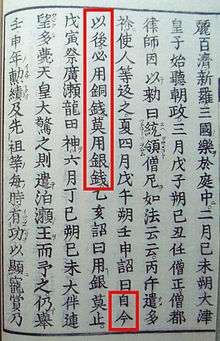

The Japanese embassy to the Tang court. The Nihon Shoki entry of 15 April 683 (Tenmu 12th year) mandates the use of copper coins.

The Nihon Shoki entry of 15 April 683 (Tenmu 12th year) mandates the use of copper coins. Known coin types of Japan from 708 to 958, chronologically arranged.

Known coin types of Japan from 708 to 958, chronologically arranged.

Japan's contacts with the Chinese mainland became intense during the Tang period, with many exchanges and cultural imports occurring.[2] The first Japanese embassy to China is recorded to have been sent in 630, following with Japan, who adopted numerous Chinese cultural practices.[1] The importance of metallic currency appeared to Japanese nobles, probably leading to some coin minting at the end of the 7th century,[2] such as the Tomimotosen coinage (富元銭), discovered in 1998 through archaeological research in the area of Nara.[1] An entry of the Nihon Shoki dated April 15, 683 mentions: "From now on, copper coins should be used, but silver coins should not be used", which is thought to order the adoption of the Tomimotosen copper coins.[1] The first official coinage was struck in 708.

Currency reform (760)

The Wadōkaichin soon became debased, as the government rapidly issued coins with progressively lesser metallic content, and local imitations thrived.[1] In 760, a reform was put in place, in which a new copper coin called Mannentsūhō (万年通寶) was worth 10 times the value of the former Wadōkaichin, with also a new silver coin named Taiheigenbō (大平元寶) with a value of 10 copper coins, as well as a new gold coin named Kaikishōhō (開基勝寶) with a value of 10 silver coins.[1]

Silver minting was soon abandoned however, but copper minting took place throughout the Nara period.[2] A variety of coin types are known, altogether 12 types, including one coin type in gold.[1]

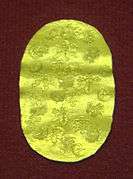

Japanese gold coin Kaikishōhō (開基勝寶) from 760.

Japanese gold coin Kaikishōhō (開基勝寶) from 760. A Silver Wadōkaichin (和同開珎) coin from 8th century Japan.

A Silver Wadōkaichin (和同開珎) coin from 8th century Japan.

Last emissions (958)

The Kōchōsen Japanese system of coinage became strongly debased, with its metallic content and value decreasing. By the middle of the 9th century, the value of a coin in rice had fallen to 1/150th of its value of the early 8th century.

By the end of the 10th century, compounded with weaknesses in the political system, this led to the abandonment of the national currency, with the return to rice as a currency medium.[1] The last official Japanese coin emission occurred in 958, with very low quality coins called Kangendaihō (乾元大寶), which soon fell into disuse.[1]

A Kangendaihō coin (乾元大寶) from 958.

A Kangendaihō coin (乾元大寶) from 958.

Chinese coinage (12–17th century)

Importation of Chinese coinage

From the 12th century, the expansion of trade and barter again highlighted the need for a currency. Chinese coinage came to be used as the standard currency of Japan, for a period lasting from the 12th to the 17th century.[1] Coins were obtained from China through trade or through "Wakō" piracy.[1] Coins were also imported from Annam (modern Vietnam) and Korea.[1]

Imitations of Chinese coinage

As the Chinese coins were not in sufficient number as trade and economy expanded, local Japanese imitations of Chinese coins were made from the 14th century, especially imitations of Ming coins, with inscribed names identical to those of contemporary Chinese coins.[1] These coins were considered as very low value compared to Chinese coins, and several of them had to be exchanged just for one Chinese coin. This situation would continue until the beginning of the Edo period, when a new system was put in place.

Northern Song Chinese coin Shèngsòng Yuánbǎo (聖宋元寶).

Northern Song Chinese coin Shèngsòng Yuánbǎo (聖宋元寶). Seisō Genbō (聖宋元宝) Japanese imitation of the Song type. 14–17th century.

Seisō Genbō (聖宋元宝) Japanese imitation of the Song type. 14–17th century. Chinese Ming coin Yǒnglè Tōngbǎo (永樂通寳) used as currency in Japan.

Chinese Ming coin Yǒnglè Tōngbǎo (永樂通寳) used as currency in Japan. Eiraku Tsūhō (永楽通宝) Japanese imitation of the Ming type. 14–17th century.

Eiraku Tsūhō (永楽通宝) Japanese imitation of the Ming type. 14–17th century. Genpu Tsūhō (元富通宝) Japanese imitation. 14–17th century.

Genpu Tsūhō (元富通宝) Japanese imitation. 14–17th century.

Local experiments (16th century)

The growth of the economy and trade meant that small copper currency became insufficient to cover the amounts that were being exchanged. During the Sengoku period, the characteristics of the future Edo Period system began to emerge. Local Lords developed trade, abolishing monopolistic guilds, which led to the need for large-denomination currencies. From the 16th century, local experiments started to be made, with the minting of local coins, sometimes in gold. Especially the Takeda clan of Kōshū minted gold coins which were later adopted by the Tokugawa shogunate.[1]

Hideyoshi unified Japan, and thus centralized most of the minting of large denomination silver and gold coins, effectively putting in place the basis of a unified currency system. Hideyoshi developed the large Ōban plate, also called the Tenshō Ōban (天正大判), in 1588, a predecessor to Tokugawa gold coinage.[3]

A common practice in that period was also to melt gold into copper molds for convenience, derived from the sycee manufacturing method. These were called Bundōkin (分銅金), of which there were two types, the small Kobundō (小分銅), and the large Ōbundō (大分銅). A Kobundō would represent about 373g in gold.[1]

Kiritomoeban (桐巴判), 16th century.

Kiritomoeban (桐巴判), 16th century. Kobundō, "Turtle scale Paulownia" Kinkōkiri mark (亀甲桐), Nunome (布目) emblem.

Kobundō, "Turtle scale Paulownia" Kinkōkiri mark (亀甲桐), Nunome (布目) emblem. Kobundō, "Fixed" Tei mark (定), Ishime (石目) emblem.

Kobundō, "Fixed" Tei mark (定), Ishime (石目) emblem. Kobundō, "happiness" Kichi mark (吉) mark, Nunome (布目) emblem.

Kobundō, "happiness" Kichi mark (吉) mark, Nunome (布目) emblem. A Kobundō (小分銅), 95–97% gold, "Paulownia" Kiri mark (桐), Kikubana (菊花) emblem, 373.11 grams, Japan.

A Kobundō (小分銅), 95–97% gold, "Paulownia" Kiri mark (桐), Kikubana (菊花) emblem, 373.11 grams, Japan. An early minting experiment by the Takeda clan of Kōshū (甲州金) in the 16th century.

An early minting experiment by the Takeda clan of Kōshū (甲州金) in the 16th century.

Tokugawa currency (17–19th century)

Tokugawa coinage was a unitary and independent metallic monetary system established by Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1601 in Japan, and which lasted throughout the Tokugawa period until its end in 1867.[4]

From 1601, Tokugawa coinage consisted in gold, silver, and bronze denominations.[4] The denominations were fixed, but the rates actually fluctuated on the exchange market.[4] Tokugawa started by minting Keicho gold and silver coins, and Chinese copper coins were later replaced by Kan’ei Tsuho coins in 1670.

The material for the coinage came from gold and silver mines across Japan. To this effect, gold mines were newly opened and exploited, such as the Sado gold mine or the Toi gold mine in Izu Peninsula. Regarding diamond coins, the Kan'ei tsūhō coin (寛永通宝) came to replace the Chinese coins that had been in circulation in Japan, as well as those that were privately minted, and became the legal tender for small denominations.[1]

Yamada Hagaki, Japan's first notes, were issued around 1600 by Shinto priests also working as merchants in the Ise-Yamada (modern Mie Prefecture), in exchange for silver.[1] This was earlier than the first goldsmith notes issued in England around 1640.[1] The first known feudal note was issued by the Fukui clan in 1661. During the 17th century, the feudal domains developed a system of feudal notes, giving currency to pledged notes issued by the lord of the domain, in exchange for convertibility in gold, silver or copper.[1] Japan thus combined gold, silver, and copper standards with the circulation of paper money.[1]

Tokugawa coinage remained in use during the "Sakoku" period of seclusion, although it progressively became debased with the attempt to resolve government deficits. The first debasement was called the Genroku Recoinage in 1695.[1]

Bakumatsu currency (1854–1868)

Tokugawa coinage fell apart following the reopening of Japan to the West in 1854, as the silver-gold rates gave huge opportunities for arbitrage to foreigners, leading to the loss of large quantities of gold to exportation.

Foreign arbitrage led to a massive outflow of gold, as gold traded for silver in Japan with a 1:5 ratio, while that ratio was 1:15 abroad. During the Bakumatsu period in 1859 Mexican dollars were even given official currency in Japan, by coining them with marks in Japanese and officializing their exchange rate of three "Bu". They were called Aratame Sanbu Sadame (改三分定, "Fixed to the value of three bu").[1]

Meanwhile, local governments issued their own currency chaotically, so that the nation’s money supply expanded by 2.5 times between 1859 and 1869, leading to crumbling money values and soaring prices. The system would be replaced by a new one, after the conclusion of the Boshin War, and with the onset of the Meiji government in 1868.[1]

A Mexican dollar used as currency in Japan, marked with "Aratame sanbu sadame" (Fixed to the value of three bu) (改三分定) from 1859.

A Mexican dollar used as currency in Japan, marked with "Aratame sanbu sadame" (Fixed to the value of three bu) (改三分定) from 1859. Allegory of inflation and soaring prices during the Bakumatsu era.

Allegory of inflation and soaring prices during the Bakumatsu era.

Imperial Japan (1871–present)

Following 1868, a new currency system based on the Japanese yen was progressively established along Western lines, which has remained Japan's currency system to this day.

Immediately after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, previous gold, silver and copper coins, as well as feudal notes were allowed continued circulation, leading to great confusion. In 1868, the government also issued coins and gold-convertible paper money, called Daijōkansatsu (太政官札), denominated in Ryō, an old unit from the Yedo period, and private banks called Kawase Kaisha were allowed to issue their own currency as well. Complexity, widespread counterfeiting of gold coins and feudal notes led to widespread confusion.[1]

Birth of the yen: New Currency Act (1871)

Through the New Currency Act of 1871, Japan adopted the gold standard along international lines, with 1 yen corresponding to 1.5g of pure gold. The Meiji government issued new notes, called Meiji Tsūhōsatsu (明治通宝札) in 1872, which were printed in Germany.[1]

Silver coins were also issued for trade with Asian countries who favoured silver as a currency, thus establishing a de facto gold-silver standard.[1]

The First Meiji one yen banknote, Meiji Tsūhōsatsu (明治通宝札) from 1871.

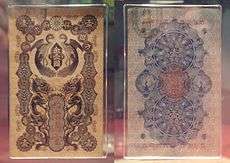

The First Meiji one yen banknote, Meiji Tsūhōsatsu (明治通宝札) from 1871. An early 1 yen banknote showing both the front and reverse. National Bank notes, 1873.

An early 1 yen banknote showing both the front and reverse. National Bank notes, 1873.

National Bank Act (1872)

The National Bank Act of 1872 led to the establishment of 4 banks between 1873 and 1874, until there were more than 153 national banks by the end of 1879. The national banks issued identically designed convertible notes, which were effective in funding the industry and progressively replaced government notes. In 1876, an amendment allowed the banks to make the banknotes virtually non convertible. These national banknotes imitated the design of American banknotes, although the name of the issuer was different for each.[1]

Severe inflation broke out with the Seinan Civil War in 1877. This was controlled by the reduction of government spending and the removal of paper currency from circulation. During the Seinan Civil War, an original type of paper money was issued by the rebel leader Saigō Takamori in order to finance his war effort.[1]

In 1881, the first Japanese note to feature a portrait, the Empress Jingū note (神功皇后札), was issued.[1]

Bank of Japan (1882)

In order to regularize the issuance of convertible banknotes, a central bank, the Bank of Japan, was established in 1882. The bank would stabilize the currency by centralizing the issuance of convertible banknotes. The first central banknotes were issued by the Bank of Japan in 1885. They were called Daikokusatsu (大黒札), and were convertible in silver.[1]

Following the devaluation of silver, and the abandon of silver as a currency standard by Western powers, Japan adopted the gold standard through the Coinage Law of 1897. The yen was fixed at 0.75g of pure gold, and banknotes were issued which were convertible into gold.[1] In 1899, the National Banks banknotes were declared invalid, leaving the Bank of Japan as the only supplier of currency.[1]

A Bank of Japan gold-convertible yen banknote from 1900.

A Bank of Japan gold-convertible yen banknote from 1900.

World Wars

During World War I, Japan prohibited the export of gold in 1917, as did many countries such as the United States. Gold convertibility was again shortly established in January 1930, only to be abandoned in 1931 when Great Britain abandoned the gold standard. Conversion of banknotes into gold was suspended.[1]

From 1941, Japan formally adopted a managed currency system, and in 1942 the Bank of Japan Law officially suppressed the obligation of conversion.[1]

Modern yen

In 1946, following the Second World War, Japan removed the old currency (旧円券) and introduced the "New Yen" (新円券).[1] Meanwhile, American occupation forces used a parallel system, called B yen, from 1945 to 1958.

Since then, together with the economic expansion of Japan, the yen has become one of the major currencies of the world.[5]

The front of a One yen bill from 1944

The front of a One yen bill from 1944 The inverse of the same One yen bill as pictured previously

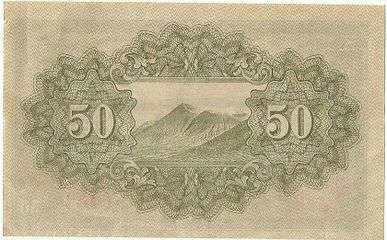

The inverse of the same One yen bill as pictured previously The front of a Japanese 50 sen bill from 1946

The front of a Japanese 50 sen bill from 1946 The Inverse of the same 50 sen bill as pictured previously

The Inverse of the same 50 sen bill as pictured previously Daijōkansatsu notes (太政官札) denominated in Ryō, 1868, Japan.

Daijōkansatsu notes (太政官札) denominated in Ryō, 1868, Japan. American banknote, and Japanese 1873 banknote closely following the U.S. design.

American banknote, and Japanese 1873 banknote closely following the U.S. design. An early one yen gold coin

An early one yen gold coin A gold standard one yen banknote from 1916

A gold standard one yen banknote from 1916 Japanese Government Asian banknotes distributed during the Second World War.

Japanese Government Asian banknotes distributed during the Second World War. Various types of "B Yen" notes used by American occupation forces in 1945–1958.

Various types of "B Yen" notes used by American occupation forces in 1945–1958._front.jpg) A Series D 2,000 yen note.

A Series D 2,000 yen note..jpg) 10 Japanese yen (1981).

10 Japanese yen (1981).

See also

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 Japan Currency Museum (日本貨幣博物館) permanent exhibit

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Cambridge history of Japan: Heian Japan John Whitney Hall, Donald H. (Donald Howard) Shively, William H. McCullough p.434

- ↑ The Cambridge History of Japan: Early modern Japan by John Whitney Hall p.61

- 1 2 3 Metzler p.15

- ↑ The internationalization of currencies: an appraisal of the Japanese yen by George S. Tavlas, Yuzuru Ozeki p.34

Further reading

- Mark Metzler (2006). Lever of empire: the international gold standard and the crisis of liberalism in prewar Japan. Volume 17 of Twentieth Century Japan: The Emergence of a World Power. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24420-6.

Early Japanese Coins. David Hartill. ISBN 978-0-7552-1365-8