Jane Eyre

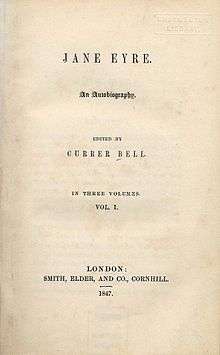

Title page of the first Jane Eyre edition | |

| Author | Charlotte Brontë |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Set in | Northern England, early 19th century[a] |

| Publisher | Smith, Elder & Co. |

Publication date | 16 October 1847 |

| Media type | |

| OCLC | 3163777 |

| 823.8 | |

| Followed by | Shirley |

| Text | Jane Eyre at Wikisource |

Jane Eyre /ˈɛər/ (originally published as Jane Eyre: An Autobiography) is a novel by English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published on 16 October 1847, by Smith, Elder & Co. of London, England, under the pen name "Currer Bell". The first American edition was published the following year by Harper & Brothers of New York.

Primarily of the Bildungsroman genre, Jane Eyre follows the emotions and experiences of its eponymous heroine, including her growth to adulthood and her love for Mr. Rochester, the Byronic[1] master of fictitious Thornfield Hall. In its internalisation of the action—the focus is on the gradual unfolding of Jane's moral and spiritual sensibility, and all the events are coloured by a heightened intensity that was previously the domain of poetry—Jane Eyre revolutionised the art of fiction. Charlotte Brontë has been called the 'first historian of the private consciousness' and the literary ancestor of writers like Proust and Joyce.[2] The novel contains elements of social criticism, with a strong sense of Christian morality at its core, but is nonetheless a novel many consider ahead of its time given the individualistic character of Jane and the novel's exploration of classism, sexuality, religion, and proto-feminism.[3][4]

Plot

Introduction

The novel is a first-person narrative from the perspective of the title character. The novel's setting is somewhere in the north of England, late in the reign of George III (1760–1820).[lower-alpha 1] It goes through five distinct stages: Jane's childhood at Gateshead Hall, where she is emotionally and physically abused by her aunt and cousins; her education at Lowood School, where she gains friends and role models but suffers privations and oppression; her time as governess at Thornfield Hall, where she falls in love with her Byronic employer, Edward Rochester; her time with the Rivers family, during which her earnest but cold clergyman cousin, St. John Rivers, proposes to her; and her reunion with, and marriage to, her beloved Rochester. During these sections, the novel provides perspectives on a number of important social issues and ideas, many of which are critical of the status quo (see the Themes section below). Literary critic Jerome Beaty opines that the close first person perspective leaves the reader "too uncritically accepting of her worldview", and often leads reading and conversation about the novel towards supporting Jane, regardless of how irregular her ideas or perspectives are.[5]

Jane Eyre is divided into 38 chapters, and most editions are at least 400 pages long. The original publication was in three volumes, comprising chapters 1 to 15, 16 to 27, and 28 to 38; this was a common publishing format during the 19th century (see three-volume novel).

Brontë dedicated the novel's second edition to William Makepeace Thackeray.

Jane's childhood

The novel begins with the titular character, Jane Eyre, aged 10, living with her maternal uncle's family, the Reeds, as a result of her uncle's dying wish. It is several years after her parents died of typhus. Mr. Reed, Jane's uncle, was the only person in the Reed family who was ever kind to Jane. Jane's aunt, Sarah Reed, dislikes her, treats her as a burden, and discourages her children from associating with Jane. Mrs. Reed and her three children are abusive to Jane, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. The nursemaid Bessie proves to be Jane's only ally in the household, even though Bessie sometimes harshly scolds Jane. Excluded from the family activities, Jane is incredibly unhappy, with only a doll and books for comfort.

One day, after her cousin John Reed knocks her down and she attempts to defend herself, Jane is locked in the red room where her uncle died; there, she faints from panic after she thinks she has seen his ghost. She is subsequently attended to by the kindly apothecary, Mr. Lloyd, to whom Jane reveals how unhappy she is living at Gateshead Hall. He recommends to Mrs. Reed that Jane should be sent to school, an idea Mrs. Reed happily supports. Mrs. Reed then enlists the aid of the harsh Mr. Brocklehurst, director of Lowood Institution, a charity school for girls. Mrs. Reed cautions Mr. Brocklehurst that Jane has a "tendency for deceit", which he interprets as her being a "liar". Before Jane leaves, however, she confronts Mrs. Reed and declares that she'll never call her "aunt" again, that Mrs. Reed and her daughter, Georgiana, are the ones who are deceitful, and that she shall tell everyone at Lowood how cruelly Mrs. Reed treated her.[6]

Lowood

At Lowood Institution, a school for poor and orphaned girls, Jane soon finds that life is harsh, but she attempts to fit in and befriends an older girl, Helen Burns, who is able to accept her punishment philosophically. During a school inspection by Mr. Brocklehurst, Jane accidentally breaks her slate, thereby drawing attention to herself. He then stands her on a stool, brands her a liar, and shames her before the entire assembly. Jane is later comforted by her friend, Helen. Miss Temple, the caring superintendent, facilitates Jane's self-defence and writes to Mr. Lloyd, whose reply agrees with Jane's. Jane is then publicly cleared of Mr. Brocklehurst's accusations.

The 80 pupils at Lowood are subjected to cold rooms, poor meals, and thin clothing. Many students fall ill when a typhus epidemic strikes, and Jane's friend Helen dies of consumption in her arms. When Mr. Brocklehurst's maltreatment of the students is discovered, several benefactors erect a new building and install a sympathetic management committee to moderate Mr. Brocklehurst's harsh rule. Conditions at the school then improve dramatically.

The name Lowood symbolizes the "low" point in Jane's life where she was maltreated. Helen Burns is a representation of Charlotte's elder sister Maria, who died of tuberculosis after spending time at a school where the children were mistreated.

Thornfield Hall

After six years as a student and two as a teacher at Lowood, Jane decides to leave, like her friend and confidante Miss Temple, who recently married. She advertises her services as a governess and receives one reply, from Alice Fairfax, housekeeper at Thornfield Hall. Jane takes the position, teaching Adèle Varens, a young French girl.

One night, while Jane is walking to a nearby town, a horseman passes her. The horse slips on ice and throws the rider. Despite the rider's surliness, Jane helps him to get back onto his horse. Later, back at Thornfield, she learns that this man is Edward Rochester, master of the house. Adèle is his ward, left in his care when her mother abandoned her.

At Jane's first meeting with him within Thornfield, Mr. Rochester teases her, accusing her of bewitching his horse to make him fall. He also talks strangely in other ways, but Jane is able to stand up to his initially arrogant manner. Mr. Rochester and Jane soon come to enjoy each other's company, and spend many evenings together.

Odd things start to happen at the house, such as a strange laugh, a mysterious fire in Mr. Rochester's room (from which Jane saves Rochester by rousing him and throwing water on him and the fire), and an attack on a house guest named Mr. Mason. Then Jane receives word that her aunt Mrs. Reed is calling for her, because she suffered a stroke after her son John died. Jane returns to Gateshead and remains there for a month, attending to her dying aunt. Mrs. Reed confesses to Jane that she wronged her, giving Jane a letter from Jane's paternal uncle, Mr. John Eyre, in which he asks for her to live with him and be his heir. Mrs. Reed admits to telling Mr. Eyre that Jane had died of fever at Lowood. Soon afterward, Mrs. Reed dies, and Jane helps her cousins after the funeral before returning to Thornfield.

Back at Thornfield, Jane broods over Mr. Rochester's rumoured impending marriage to the beautiful and talented, but snobbish and heartless, Blanche Ingram. However, one midsummer evening, Rochester baits Jane by saying how much he will miss her after getting married, but how she will soon forget him. The normally self-controlled Jane reveals her feelings for him. Rochester is then sure that Jane is sincerely in love with him, and he proposes marriage. Jane is at first sceptical of his sincerity, but eventually believes him and gladly agrees to marry him. She then writes to her Uncle John, telling him of her happy news.

As she prepares for her wedding, Jane's forebodings arise when a strange woman sneaks into her room one night and rips her wedding veil in two. As with the previous mysterious events, Mr. Rochester attributes the incident to Grace Poole, one of his servants. During the wedding ceremony, Mr. Mason and a lawyer declare that Mr. Rochester cannot marry because he is already married to Mr. Mason's sister, Bertha. Mr. Rochester admits this is true but explains that his father tricked him into the marriage for her money. Once they were united, he discovered that she was rapidly descending into congenital madness, and so he eventually locked her away in Thornfield, hiring Grace Poole as a nurse to look after her. When Grace gets drunk, Rochester's wife escapes and causes the strange happenings at Thornfield.

It turns out that Jane's uncle, Mr. John Eyre, is a friend of Mr. Mason's and was visited by him soon after Mr. Eyre received Jane's letter about her impending marriage. After the marriage ceremony is broken off, Mr. Rochester asks Jane to go with him to the south of France, and live with him as husband and wife, even though they cannot be married. Refusing to go against her principles, and despite her love for him, Jane leaves Thornfield in the middle of the night.[7]

Other employment

Jane travels as far from Thornfield as she can using the little money she had previously saved. She accidentally leaves her bundle of possessions on the coach and has to sleep on the moor, and unsuccessfully attempts to trade her handkerchief and gloves for food. Exhausted and hungry, she eventually makes her way to the home of Diana and Mary Rivers, but is turned away by the housekeeper. She collapses on the doorstep, preparing for her death. St. John Rivers, Diana and Mary's brother and a clergyman, saves her. After she regains her health, St. John finds Jane a teaching position at a nearby village school. Jane becomes good friends with the sisters, but St. John remains aloof.

The sisters leave for governess jobs, and St. John becomes somewhat closer to Jane. St. John learns Jane's true identity and astounds her by telling her that her uncle, John Eyre, has died and left her his entire fortune of 20,000 pounds (equivalent to over £1.3 million in 2011[8]). When Jane questions him further, St. John reveals that John Eyre is also his and his sisters' uncle. They had once hoped for a share of the inheritance but were left virtually nothing. Jane, overjoyed by finding that she has living and friendly family members, insists on sharing the money equally with her cousins, and Diana and Mary come back to live at Moor House.

Proposals

Thinking Jane will make a suitable missionary's wife, St. John asks her to marry him and to go with him to India, not out of love, but out of duty. Jane initially accepts going to India but rejects the marriage proposal, suggesting they travel as brother and sister. As soon as Jane's resolve against marriage to St. John begins to weaken, she mysteriously hears Mr. Rochester's voice calling her name. Jane then returns to Thornfield to find only blackened ruins. She learns that Mr. Rochester's wife set the house on fire and committed suicide by jumping from the roof. In his rescue attempts, Mr. Rochester lost a hand and his eyesight. Jane reunites with him, but he fears that she will be repulsed by his condition. "Am I hideous, Jane?", he asks. "Very, sir: you always were, you know", she replies. When Jane assures him of her love and tells him that she will never leave him, Mr. Rochester again proposes, and they are married. He eventually recovers enough sight to see their firstborn son.

Characters

- Jane Eyre: The novel's protagonist, second wife of Edward Rochester, and title character. Orphaned as a baby, she struggles through her nearly loveless childhood and becomes governess at Thornfield Hall. Jane is passionate and strongly principled, and values freedom and independence. She also has a strong conscience and is a determined Christian.

- Mr. Reed: Jane's maternal uncle, who adopts Jane when her parents die. According to Mrs. Reed, he pitied Jane and often cared for her more than for his own children. Before his own death, he makes his wife promise to care for Jane.

- Mrs. Reed: Jane's aunt by marriage, who adopts Jane on her husband's wishes, but abuses and neglects her. She eventually casts her off and sends her to Lowood School.

- John Reed: Jane's cousin who bullies her incessantly, sometimes in his mother's presence. John ruins himself as an adult by drinking and gambling, and is thought to have committed suicide.

- Eliza Reed: Jane's cousin. Jealous of her more attractive sister and a slave to rigid routine, she self-righteously devotes herself to religion. She leaves for a nunnery near Lisle after her mother's death, determined to estrange herself from her sister.

- Georgiana Reed: Jane's cousin. Although beautiful and indulged, she is insolent and spiteful. Her sister Eliza foils Georgiana's marriage to the wealthy Lord Edwin Vere, when the couple is about to elope. Georgiana eventually marries a, "wealthy worn-out man of fashion."

- Bessie Lee: The nursemaid at Gateshead. She often treats Jane kindly, telling her stories and singing her songs, but she has a quick temper. Later, she marries Robert Leaven.

- Robert Leaven: The coachman at Gateshead, who brings Jane the news of John Reed's death, which has brought on Mrs. Reed's stroke, and Mrs. Reed's wish to see Jane before Mrs. Reed died.

- Mr. Lloyd: A compassionate apothecary who recommends that Jane be sent to school. Later, he writes a letter to Miss Temple confirming Jane's account of her childhood and thereby clears Jane of Mrs. Reed's charge of lying.

- Mr. Brocklehurst: The clergyman, director, and treasurer of Lowood School, whose maltreatment of the students is eventually exposed. A religious traditionalist, he advocates for his charges the most harsh, plain, and disciplined possible lifestyle, but not, hypocritically, for himself and his own family. His second daughter Augusta exclaimed, "Oh, dear papa, how quiet and plain all the girls at Lowood look... they looked at my dress and mama's, as if they had never seen a silk gown before."

- Miss Maria Temple: The kind superintendent of Lowood School, who treats the students with respect and compassion. She helps clear Jane of Mr. Brocklehurst's false accusation of deceit and cares for Helen in her last days. Eventually, she marries Reverend Naysmith.

- Miss Scatcherd: A sour and strict teacher at Lowood. She constantly punishes Helen Burns for her untidiness but fails to see Helen's substantial good points.

- Helen Burns: Jane's best friend at Lowood School. She refuses to hate those who abuse her, trusts in God, and prays for peace one day in heaven. She teaches Jane to trust Christianity and dies of consumption in Jane's arms. Elizabeth Gaskell, in her biography of the Brontë sisters, wrote that Helen Burns was 'an exact transcript' of Maria Brontë, who died of consumption at age 11.[9]

- Edward Fairfax Rochester: The master of Thornfield Hall. A Byronic hero, he is tricked into making an unfortunate first marriage to Bertha Mason many years before he meets Jane, with whom he falls in love.

- Bertha Antoinetta Mason: The violent and insane first wife of Edward Rochester. Bertha moved to Thornfield, was locked in the attic, and eventually committed suicide after setting Thornfield Hall aflame.

- Adèle Varens: [a.dɛl va.ʁɛ̃] An excitable French child to whom Jane is governess at Thornfield. Adèle's mother was a dancer named Céline. She was Mr. Rochester's mistress and claimed that Adèle was Mr. Rochester's daughter, though he refuses to believe it due to Céline's unfaithfulness and Adèle's apparent lack of resemblance to him. Adèle seems to believe that her mother is dead (she tells Jane in chapter 11, "I lived long ago with mamma, but she is gone to the Holy Virgin"), but Mr Rochester later tells Jane that Céline actually abandoned Adèle and "ran away to Italy with a musician or singer" (ch. 15). Adèle and Jane develop a strong liking for one another, and although Mr. Rochester places Adèle in a strict school after Jane flees Thornfield, Jane visits Adèle after her return and finds a better, less severe school for her. When Adèle is old enough to leave school, Jane describes her as "a pleasing and obliging companion – docile, good-tempered and well-principled", and considers her kindness to Adèle well repaid.

- Mrs. Alice Fairfax: An elderly, kind widow and the housekeeper of Thornfield Hall.

- Leah: The housemaid at Thornfield Hall.

- John: An old, and normally the only, manservant at Thornfield.

- Mary: Normally referred to as 'John's wife' and sometimes 'the cook'.

- Blanche Ingram: A socialite whom Mr. Rochester temporarily courts to make Jane jealous. Ms. Ingram is described as having great beauty and talent, but displays callous behaviour and avaricious intent.

- Richard Mason: An Englishman from the West Indies, whose sister is Mr. Rochester's first wife. He took part in tricking Mr. Rochester into marrying Bertha. He still, however, cares for his sister's well-being.

- Grace Poole: Bertha Mason's caretaker. Mr. Rochester pays her a very high salary to keep Bertha hidden and quiet, and she is often used as an explanation for odd happenings. She has a weakness for drink that occasionally allows Bertha to escape.

- St. John Eyre Rivers: A clergyman who befriends Jane and turns out to be her cousin. St. John is thoroughly practical and suppresses all of his human passions and emotions in favour of good works. He is determined to go to India as a missionary, despite being in love with Rosamond Oliver.

- Diana and Mary Rivers: St. John's sisters and (as it turns out) Jane's cousins. They are poor, intelligent, and kind-hearted, and want St. John to stay in England.

- Rosamond Oliver: A beautiful, kindly, wealthy, but not deep thinking, young woman, and the patron of the village school where Jane teaches. Rosamond falls in love with St. John, only to be rejected because she would not make a good missionary's wife.

- Mr. Oliver: Rosamond Oliver's wealthy father, who owns a foundry and needle factory in the district. He is a kind and charitable man, and is fond of St. John.

- Alice Wood: Jane's maid when Jane is mistress of the girls' village school in Morton.

- John Eyre: Jane's paternal uncle, who leaves her his vast fortune and wished to adopt her when she was 15. Mrs. Reed prevented the adoption out of spite towards Jane.

Context

The early sequences, in which Jane is sent to Lowood, a harsh boarding school, are derived from the author's own experiences. Helen Burns's death from tuberculosis (referred to as consumption) recalls the deaths of Charlotte Brontë's sisters Elizabeth and Maria, who died of the disease in childhood as a result of the conditions at their school, the Clergy Daughters School at Cowan Bridge, near Tunstall, Lancashire. Mr. Brocklehurst is based on Rev. William Carus Wilson (1791–1859), the Evangelical minister who ran the school. Additionally, John Reed's decline into alcoholism and dissolution recalls the life of Charlotte's brother Branwell, who became an opium and alcohol addict in the years preceding his death. Finally, like Jane, Charlotte became a governess. These facts were revealed to the public in The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857) by Charlotte's friend and fellow novelist Elizabeth Gaskell.[12]

The Gothic manor of Thornfield Hall was probably inspired by North Lees Hall, near Hathersage in the Peak District. This was visited by Charlotte Brontë and her friend Ellen Nussey in the summer of 1845 and is described by the latter in a letter dated 22 July 1845. It was the residence of the Eyre family, and its first owner, Agnes Ashurst, was reputedly confined as a lunatic in a padded second floor room.[12]

It has been suggested that the Wycoller Hall in Lancashire, close to Haworth, provided the setting for Ferndean Manor to which Mr. Rochester retreats after the fire at Thornfield: there are similarities between the owner of Ferndean, Mr. Rochester's father, and Henry Cunliffe who inherited Wycoller in the 1770s and lived there until his death in 1818; one of Cunliffe's relatives was named Elizabeth Eyre (née Cunliffe).[13]

The sequence in which Mr. Rochester's wife sets fire to the bed curtains was prepared in an August 1830 homemade publication of Brontë's The Young Men's Magazine, Number 2.[14]

Charlotte Brontë began composing Jane Eyre in Manchester, and she likely envisioned Manchester Cathedral churchyard as the burial place for Jane's parents and the birthplace of Jane herself.[15]

Adaptations and influence

The novel has been adapted into a number of other forms, including theatre, film, television - and at least two full-length operas, by John Joubert (1987–97) and Michael Berkeley (2000). The novel has also been the subject of a number of significant rewritings and reinterpretations, notably Jean Rhys's seminal novel Wide Sargasso Sea.

Reception

Although Jane Eyre is now commonly accepted in the canon of English literature and is widely studied in secondary schools, its immediate reception was in stark contrast to its contemporary reception. In 1848, Elizabeth Rigby (later Elizabeth Eastlake), reviewing Jane Eyre in The Quarterly Review, found it "pre-eminently an anti-Christian composition,"[16] declaring: "We do not hesitate to say that the tone of mind and thought which has overthrown authority and violated every code human and divine abroad, and fostered Chartism and rebellion at home, is the same which has also written Jane Eyre."[16]

In 2003, the novel was ranked number 10 in the BBC's survey The Big Read.[17]

Notes

References

- ↑ Harold Bloom declared Eyre a "classic of Gothic and Victorian literature." Bloom, Harold (July 2007). "Charlotte Brontë's "Jane Eyre"". Midwest Book Review. Chelsea House Publishers: 245.

- ↑ Burt, Daniel S. (2008). The Literature 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Novelists, Playwrights, and Poets of All Time. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438127064.

- ↑ Gilbert, Sandra & Gubar, Susan (1979). The Madwoman in the Attic. Yale University Press.

- ↑ Martin, Robert B. (1966). Charlotte Brontë's Novels: The Accents of Persuasion. NY: Norton.

- ↑ Beaty, Jerome. "St. John's Way and the Wayward Reader" in Brontë, Charlotte (2001) [1847]. Richard J. Dunn, ed. Jane Eyre (Norton Critical Edition, Third ed.). W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 491–502. ISBN 0393975428.

- ↑ Brontë, Charlotte (16 October 1847). Jane Eyre. London, England: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 105.

- ↑ Brontë, Charlotte (2008). Jane Eyre. Radford, Virginia: Wilder Publications. ISBN 160459411X.

- ↑ calculated using the UK Retail Price Index: "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ↑ Gaskell, Elizabeth (1857). The Life of Charlotte Brontë. 1. Smith, Elder & Co. p. 73.

- ↑ "Jane Eyre: a Mancunian?". BBC. 10 October 2006. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ "Salutation pub in Hulme thrown a lifeline as historic building is bought by MMU". Manchester Evening News. 2 September 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- 1 2 Stevie Davies, Introduction and Notes to Jane Eyre. Penguin Classics ed., 2006.

- ↑ "Wycoller Sheet 3: Ferndean Manor and the Brontë Connection" (pdf). Lancashire Countryside Service Environmental Directorale. 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ↑ "Paris museum wins Brontë bidding war". BBC News. 15 December 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ↑ Alexander, Christine, and Sara L. Pearson. Celebrating Charlotte Brontë: Transforming Life into Literature in Jane Eyre. Brontë Society, 2016, p. 173.

- 1 2 Shapiro, Arnold (Autumn 1968). "In Defense of Jane Eyre". Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900. 8 (4): 683. JSTOR 449473.

- ↑ "The Big Read". BBC. April 2003. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

External links

- Works by Charlotte Brontë at DMOZ

- Jane Eyre at the British Library

- Jane Eyre at The Victorian Web

- Jane Eyre at the Internet Archive

- Jane Eyre at Project Gutenberg

Jane Eyre public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Jane Eyre public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Dating Jane Eyre