Jameson's mamba

| Jameson's mamba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Elapidae |

| Genus: | Dendroaspis |

| Species: | D. jamesoni |

| Binomial name | |

| Dendroaspis jamesoni (Traill, 1843)[1] | |

| |

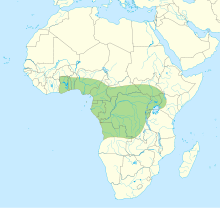

| Range of Jameson's mamba | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

Jameson's mamba (Dendroaspis jamesoni ) is a species of quick, highly arboreal and highly venomous snake of the family Elapidae. The species is endemic to Africa.

Taxonomy

Jameson's mamba was first described in 1843 by Thomas Traill, a Scottish physician, zoologist and scholar of medical jurisprudence.[3] In 1936, Arthur Loveridge described two subspecies, the nominotypical D. jamesoni jamesoni and D. jamesoni kaimosae; the latter is commonly referred to as eastern Jameson's mamba or the black-tailed Jameson's mamba.[1]

The generic name, Dendroaspis, derives from Ancient Greek dendro (δένδρο), meaning "tree",[4] and aspis (ασπίς), which is understood to mean "shield",[5] but also denotes "cobra" or simply "snake", in particular "snake with hood (shield)". Via Latin aspis, it is the source of the English word "asp". In ancient texts, aspis or asp often referred to the Egyptian cobra (Naja haje), in reference to its shield-like hood.[6] Thus, "Dendroaspis" literally means tree asp, reflecting the arboreal nature of most of the species within the genus. The genus was first described by the German ornithologist and herpetologist Hermann Schlegel in 1848.[7] Slowinski et al. (1997) pointed out that the relationships of the African genus Dendroaspis are problematical.[8] However, evidence suggests that Dendroaspis, Ophiophagus, Bungarus, and Hemibungarus form a solid non-coral snake Afro-Asiatic clade.[9]

The origins of the specific name, jamesoni, are not fully understood, but it is possible that Traill named the species in honour of Robert Jameson (1774-1854), who was a contemporary of Traill's and was the Regius Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh University where Traill studied.[10] Also, Traill was a member of the Wernerian Natural History Society, which was founded by Jameson.[11] The subspecies D. jamesoni kaimosae takes its type locality name from the Kaimosi Forest in western Kenya.[2]

Description

Jameson's mamba is a large, slender elapid snake with smooth scales and a long tapering tail which typically accounts for 20 to 25% of its total length.[12] The average length of an adult snake is approximately 1.5 meters (4.9 ft) to 2.2 meters (7.2 ft). They grow as large as 2.64 meters (8 ft 8 in).[12] Adults tend to be dull green across the back, blending to pale green towards the underbelly with scales generally edged with black.[13] The ventral side, neck and throat are typically cream or yellowish in colour.[12] Jameson's mambas have a narrow and elongated head containing a small eye and round pupil.[12] Like the western green mamba, the neck may be flattened. The subspecies D. jamesoni kaimosae, which is typically found in the eastern part of the species' range, feature a black tail while central and western examples typically have a pale green or yellow tail.[12] No significant sexual dimorphism has been observed between male and female snakes.[14]

Scalation

The head, body and tail scalation of the Jameson's mamba:[12][15]

|

|

Distribution and habitat

Jameson's mamba occurs mostly in Central Africa and West Africa, and in some parts of East Africa.[2] In Central Africa they can be found from Angola northwards to the Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, and as far north as the Imatong Mountains of South Sudan.[12] In West Africa they range from Ghana eastwards to Togo, Nigeria, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon.[2] In East Africa they can be found in Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania.[12] The subspecies D. jamesoni kaimosae is endemic to East Africa and chiefly found in western Kenya, from where it takes its type locality, as well as Uganda, Rwanda and adjacent Democratic Republic of Congo.[2] It is a relatively common and widespread snake, particularly across its western range.[14]

Found in primary and secondary rainforests, woodland, forest-savanna and deforested areas at elevations up to 2,200 metres (7,200 ft) high.[12] Jameson's mamba is an adaptable species, found in areas where there has been extensive deforestation and human development. They are often found around buildings, town parks, farmlands and plantations.[12] Jameson's mamba is a highly arboreal snake, more so than its close relatives the eastern green mamba and western green mamba, and significantly more so than the black mamba.[14]

Behaviour and ecology

Jameson's mamba is a highly agile and almost exclusively arboreal snake. Like other mambas it is capable of flattening its neck in mimicry of a cobra when it feels threatened and its body shape and length give an ability to strike at significant range. It is not typically aggressive in nature and will almost always attempt to escape.[12][14]

Diet and predators

Jameson's mamba will chase prey, similar to other mamba species. When prey is caught, Jameson's mamba will strike until the prey dies.[13] Since this species is arboreal, birds make up a large portion of their diet. Small mammals such as mice, rats, and bats and small lizards are also preyed upon.[16]

The main predators of this species are various birds of prey, including the martial eagle, bateleur, and the Congo serpent eagle. Other predators may include the honey badger, other snakes, and species of mongoose may also occasionally prey on the Jameson's mamba.[17]

Venom

Like other mambas, the venom of the Jameson's mamba is a highly neurotoxic venom. Its other components include cardiotoxins,[18] and fasciculins.[13] Its venom may also have hemotoxic and myotoxic components to it.[19] The average venom yield per bite for this species is 80 mg, but some specimens may yield as much as 120 mg in a single bite. The SC LD50 for this species according to Brown (1973) is 1.0 mg/kg, while the IV LD50 is 0.8 mg/kg.[20] Untreated envenomation may cause death within 30 to 120 minutes.[21] However, the average death time for untreated bite victims is usually two to three hours post-envenomation, but it may take up to four to six hours or longer.[16] The mortality rate of untreated bites is not exactly known, but it's said to be very high.[13]

References

- 1 2 "Dendroaspis jamesoni (Taxonomic Serial No.: 700482)". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Uetz, Peter. "Dendroaspis jamesoni (TRAILL, 1843)". The Reptile Database. www.reptile-database.org. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ↑ Traill, Thomas (1843). "Description of the Elaps Jamesoni [sic], a New Species from Demerara". Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. 34: 53–55.

- ↑ "dendro-". Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 10th Edition. HarperCollins Publishers. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "Definition of "aspis" - Collins English Dictionary". collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ "aspis, asp". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "Dendroaspis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ↑ Slowinski, JB; Knight, A; Rooney, AP (December 1997). "Inferring species trees from gene trees: A phylogenetic analysis of the Elapidae (Serpentes) based on the amino acid sequences of venom proteins". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 349–62. PMID 9417893. doi:10.1006/mpev.1997.0434.

- ↑ Castoe, TA; Smith, EN; Brown, RM; Parkinson, CL. "Higher-level phylogeny of Asian and American coralsnakes, their placement within the Elapidae (Squamata), and the systematic affinities of the enigmatic Asian coral snake Hemibungarus calligaster (Wiegmann, 1834)" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 151: 809–831. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00350.x. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M. (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Dendroaspis jamesoni, p. 133).

- ↑ Scholarly Societies Project, Wernerian Natural History Society.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Spawls, Stephen; Kim Howell; Robert Drewes; James Ashe (2002). A Field Guide to the Reptiles of East Africa. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 463–464. ISBN 978-0-7136-6817-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Clinical Toxinology Resource (Dendroaspis jamesoni)

- 1 2 3 4 Luiselli, Luca; Francesco M. Angelici; Godfrey C. Akani (2000). "Large elapids and arboreality: the ecology of Jameson’s green mamba (Dendroaspis jamesoni ) in an Afrotropical forested region". Contributions to Zoology. 69 (3). Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ Loveridge, Arthur (1 May 1936). "New tree snakes of the genera Thrasops and Dendraspis from Kenya Colony". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 49: 63–66. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- 1 2 Ernst, Carl H.; Zug, George R. (1996). Snakes in Question: The Smithsonian Answer Book. Washington, District of Columbia, USA: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. ISBN 1-56098-648-4.

- ↑ Mattison, Chris (1987-01-01). Snakes of the World. New York: Facts on File, Inc. p. 164.

- ↑ van Aswegen G, van Rooyen JM, Fourie C, Oberholzer G. (May 1996). "Putative cardiotoxicity of the venoms of three mamba species.". Journal of Wilderness and Environmental Medicine. 7 (2): 115–21. PMID 11990104. doi:10.1580/1080-6032(1996)007[0115:PCOTVO]2.3.CO;2.

- ↑ "Living Hazards Database". Armed Forces Pest Management Board. United States Department of Defense (DoD). Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ↑ Brown, John H. (1973). Toxicology and Pharmacology of Venoms from Poisonous Snakes. Springfield, Illinois, USA: Charles C. Thomas. p. 81. ISBN 0-398-02808-7.

- ↑ Davidson, Terence. "IMMEDIATE FIRST AID". University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2011-11-10.

External links

- Youtube.com - Milking venom of a black-tailed Jameson's mamba