Jackson Homestead

|

Jackson Homestead | |

Jackson Homestead | |

| |

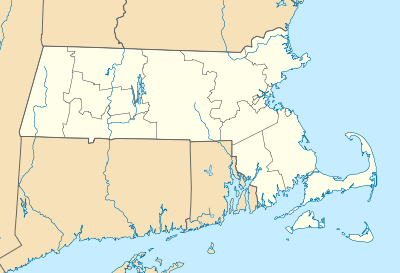

| Location | Newton, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°21′19″N 71°11′43″W / 42.35528°N 71.19528°WCoordinates: 42°21′19″N 71°11′43″W / 42.35528°N 71.19528°W |

| Built | 1809 |

| Architect | Unknown |

| Architectural style | Federal |

| NRHP Reference # | 73000306[1] |

| Added to NRHP | June 4, 1973 |

The Jackson Homestead, located at 527 Washington Street, in the village of Newton Corner, in Newton, Massachusetts, is an historic house that served as a station on the Underground Railroad before the Civil War.

It was built in 1809 in the Federal style by Timothy Jackson (1756–1814) on his family's farm. His son William Jackson (1763–1855) lived in it from 1820 until his death. William Jackson was an abolitionist and was active in politics on the local, state and national levels and served in the United States Congress from 1833 to 1837. The home was occupied by his family until 1932 when it was rented out. In 1949 it was given to the city of Newton and in 1950 the Newton History Museum was established there.[2]

History of the Homestead

Edward Jackson

Edward Jackson was born in 1602, in the East End of London. Like his father, he was a nailmaker, and amassed a small fortune so that shortly after his arrival in New England, around 1642, he was able to purchase a house with several acres of land on Newton Corner. He would eventually become the largest landowner in Newton. His wife, Frances, died shortly after his arrival; little is known but for the fact that she produced a son, Sebas, who is believed to have been born over the Atlantic Ocean because his name is a contraction of the words sea born. There are no records of Sebas's older siblings, although they did exist; they are not identified and only Sebas is mentioned in Edward's will.

Edward was admitted as a Freeman in 1645, at the age of 43, became a Cambridge Proprietor and was quickly immersed in the civil and religious life of colony and town alike. For nearly two decades Edward Jackson was Deputy to the Central Court, where he served on many committees, many of them focused on surveying and planning new settlements. It is known that Edward married a widow named Elizabeth Oliver, who was believed to have been present at every local birth for fifty years, earning herself the title of Mother of the Village. Nothing else is known about her.

In about 1654, when Edward was about 52 years old, about a dozen families living south of the Charles were tired of making the long journey to the Cambridge meeting house and back for every committee meeting and discussion. When they started holding their own services, it is likely and easily imaginable that they met in the large, new, conveniently located mansion Edward had just built near the Brighton-Newton border. The separation of Newton from Cambridge, in which Edward played a leading role, had begun.

Sebas Jackson

When Edward Jackson died in 1681 at the age of 79, his youngest son, Sebas, was about 39 years old, if it is assumed that he was born in 1642, while his parents sailed from London to a seaport in New England. During his lifetime, it is known that Edward had given or promised much of his lands and property to his children, including one gift, confirmed in his will, of a house and 150 acres (0.61 km2) of land to his son Sebas.

Unfortunately, not much is confirmed about Edward's youngest child. Although his father had left him a fine library, Sebas was unable to sign his own name. He did some town duties, serving as hogreeve, constable, and just before he died, the surveyor of highways. In 1671, when he married Sarah Baker of Roxbury, and it was most likely then that he moved into the house and took hold of the land Edward had left him.

Sarah and Sebas had five children: Edward, John, Jonathan, two daughters, and Joseph. On Sebas's death in 1690, his eldest son Edward, the only child who was of age, received 60 acres (240,000 m2) on the western side of the farm, where he built his house, while Sarah most likely stayed in the homestead, tending to the five younger children.

Joseph Jackson

Joseph was born only a few months before his father, Sebas, died. He lived with his mother, Sarah, and his siblings until they married, on the homestead until he was seventeen. However, when he, the youngest of Sebas's six children, finally came of age, his father's estate was finally divided among the six. Sarah gave up all rights to her property in exchange for financial support. Joseph took the homestead, as all other siblings were long married, wed a woman named Patience Hyde, and became a clothier. Sadly, for many years Joseph was involved in representing himself, his mother, and his two sisters in a litigation suit against his oldest brother, Edward, over the estate of their brother Jonathan, who had disappeared while on a logging expedition to the Gulf of Mexico. The bitter feud had hardly died down when Sarah died in 1726, launching a fresh round of legal battles. By the time everything was finally settled, Joseph was so experienced in law that he was able to represent Newton in a lawsuit against Cambridge over support for the Great Bridge over the Charles River. Towards the end of his life Joseph became too weak to walk and was forced to sit in a special chair while doing chores around the farm; a century later the chair was celebrated in a poem by his great-great-granddaughter, Marion Jackson-Gilbert, and is still exhibited at the museum.

Lieutenant Timothy Jackson

Joseph and Patience had at least four children: Lieutenant Timothy Jackson, another son, and two or more daughters. In 1750, when Joseph was frail and nearly 60 years old, he had given the eastern end of the house to Timothy, where he lived with his wife, formerly Sarah Smith, from their marriage in 1752. Joseph and Patience continued to live in the western half until Joseph died in 1768, from which point she lived there alone. Under the terms of Joseph's will, Timothy became responsible for all of Joseph's debts, made cash payments to his mother and unknown sisters, and in return was supposed to receive all real estate when Patience died. However, she ended up outliving him for a year, and Timothy never got his debts or papers in order. He was described as an "unfocused" man who had been weakened by consumption in the French Wars.

Major Timothy

Lieutenant Timothy and Sarah had five children: Major Timothy, born in 1756, Lucy, and three other, youngest daughters. About a year after Lieutenant Timothy had died, just after Patience's death, Sarah and the daughters were left to care for the farm as young Timothy went off to fight in the American Revolutionary War. He was gone, off and on, for five years from about 1775 to 1780, when he came home for good, at the age of just 24, having gone on a spree of dangerous and exhausting adventures, without being "...broken in constitution or in character" like his father.

When Timothy came home, his father's estate was settled for good, most likely because of the efforts of Moses Souther, who had married Lucy and worked hard to organize the farm, taking on most male responsibility, in his absence. Timothy got two- thirds of the homestead and all the real estate, and in return assumed all the debts, most financial responsibility, and supported his sisters. Timothy worked hard on the farm for the next eight years, trying patiently to get the family's affairs in order. During two of those years, he taught at a local school and it is possible that Souther also took a job there. In 1791, when he was 35, he was appointed the deputy sheriff of Middlesex County, and life began to improve. By 1802 he was able to start a soap and candle factory with the help of others most likely including Moses Souther and Lucy, and it was the success of the factory which helped improve the fortunes of the Jacksons for good.

Over the years Major Timothy worked to increase the size of the farm until spread about 20 acres (81,000 m2) north of County Road and twenty-seven acres south of it, the boundaries extending from about Smelt Brook to Hovey Street, and from Waban Park until about halfway up Mount Ida. He worked with Moses Souther to make improvements on the landscape, particularly on the hill near the homestead, where they erected "...some miles of stone wall" and replaced what had been rough, unused pasture-land with useful, visually appealing fruit orchards.

Hardworking Timothy, determined to excel in the areas in which his father had failed, soon became the most famous of all the Jacksons. He was appointed Brigade Major of the Middlesex Brigade in 1793, when he was just 37 years old. He became a Justice of the Peace shortly after, and served as Massachusetts State Representative from 1797 until just before his death. He ran for the United States Congress unsuccessfully. He was also active and respected locally, attending and participating in events not only in Newton but in Cambridge, Roxbury, and the Brighton area as well.He served on the school committee, was a Selectman of Newton for many years and also earned the title of Moderator of Town Meetings, a high honor indeed.

In 1809, Timothy Jackson decided to replace the old homestead with "a fine house for... the (modern) times." He designed and helped build a large, two-family house, hoping that his youngest son, Edmund, would possibly move into it if he married. The house was a great improvement on the original, featuring such improvements as an inside well, a laundry, storeroom and ell, magnificent fireplaces with huge mantelpieces, a great staircase and airy, small private bedchambers on the second floor, with a large, useful "garret" extending on top of the entire house. (The house is described in lavish detail on page 11 of the informative pdf file on the Jackson website.[3]) Timothy Jackson had built what is now known today as the Jackson Homestead.

He was highly respected by family, town, and politicians alike, and paid little interest to religious affairs, although his wife, Sarah (Winchester) Jackson, relied heavily upon them. With remarkable foresight and planning no doubt spurred by the court battles of previous Jackson generations, Timothy did not leave a will, but having given generously to his sons throughout his periods of financial security, he asked that his estate be divided "equally" between them and that their mother be "looked after", a fair and wise choice of words.

William Jackson

Timothy Jr. and Sarah had six children: Sons William, George, Francis, Stephen, and Edmund, and a youngest daughter, Lucretia, who was noted to be "...spoiled and pampered... a pretty little thing", most likely named after Lucy.

Born in 1783, William was educated at the local school, where Timothy had taught, and was briefly enrolled in Dr. Stearn's Academy on Galen Street. When he was fifteen, just a few years before his father's death in 1815, he was unfortunate to be stricken with a severe leg injury which would lame him for life. Confined to his bed for what some critics say was the winter of 1808-1809, it was a blow to Sarah and Lucretia. Timothy was in a slight but steady decline, and William had a high chance of dying or becoming an invalid, both of which would dash his hopes of becoming a wealthy, famous scholar or politician. However, that winter, the Newton library had opened, Timothy was unusually healthy, and William reported to have learned more than he ever had in all his years of schooling, curled up in his upstairs bedroom with a stack of useful old tomes. The next few years continued on uneventfully and happily.

When he was seventeen, William moved to Boston to work in the soap and candle factory his father had started. He soon gained respect and a reputation, and was shortly the foreman and eventually, the owner. During his years in Boston, he married a woman named Hannah Woodward. With her he had children Sarah, Timothy, and Marion, and 2 more daughters. After Hannah's death in 1812, when he was only 29 but already a respected figure, William married a woman named Mary Bennett. With her he had a daughter named Frances, unknown sons, unknown daughters, daughters Cornelia, Ellen, and Caroline, and a son named William Ward. Meanwhile, William continued to take new jobs and try new things. While he certainly amassed an astounding degree of respect and expertise, it is known that his tendency to try new hobbies was annoying at the least, frightening at most.

During his time in Boston, William made fortunes, but also lost them. He represented Boston in the General Court, and became deeply involved in the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association and similar enterprises. However, feeling that his extensive public commitments and jobs were taking a toll on his private life, as he now had a wife and at least twelve children to support and interact with, he retired back to Newton, hoping to be a farmer, at about 1820, when he was roughly 37 years old. After Timothy's death, the shares of his property were divided as equally as possible between his sons and Lucretia's survivors. When William moved back to Newton, now a rich, grown man who was well known throughout the Boston area, he bought Edward and George's shares and made a "division" with Francis and Stephen, according to which they took the land to the south of Washington street and he got the homestead and everything to the north. Adjustments were made to the house, most notably the creation and splitting of bedrooms, to accommodate the large family, the house was painted yellow with the same cream trim and green shutters the Homestead has today, and central heating would eventually be installed in the 1830s. As his daughter Ellen quotes in page 13 of,[3] "The orchards yielded apples, peaches, apricots, plums, and cherries; there was a grape arbor beyond the barn and a flourishing flower garden in which lilacs and roses abounded." Everything was set for a happy, quiet retirement, where William's sons could mature and his daughters marry, and the family fortunes continue in prosperity.

However, he soon found himself to be just as active as ever. By 1825 he was Chairman of the Board of Selectmen. One of the Board's various tasks and duties was the licensing and regulation of the "purveyors of ardent liquors", which he refused to grant until the regulations were more strictly enforced. Due almost completely to his influence, and despite horrific unpleasantness, opposition, and threats which terrified the "womenfolk" of his large household, namely the daughters of Hannah Jackson, Sarah, Marion, and their two sisters, and the daughters of Mary Jackson, Frances, unknown daughters, and Cornelia, Ellen, and Caroline, and of course Mary Jackson herself, who was now the maternal head of the Jackson household, Timothy having died in 1815 and Sarah soon after, Newton stayed dry and sober that year.

The window into the world of drinking William had gained in just those few months horrified and moved him so much that despite the cautionings of his daughters, he was a prime founder of the Newton Temperance Society and the treasurer as well as secretary. After over a year of monthly meetings devoted solely to alcohol and temperance, interest waned and the Society was modified to a Lyceum in which all topics were discussed and debated. Almost by accident, William found himself scheduled to give a talk on railroads. Railroads and trains quickly became his lifelong interest, and he was eventually associated and involved with no fewer than seven railway companies and groups. It was due largely to his influence and support that a regular railway service was built between Newton and Boston in 1844, and he was among the first to start planning for the effect of this on real estate and housing values in Newton and Brighton.

In 1832–33, William Jackson represented Newton in the General Court. He became very active in various anti-Masonic movements and as a result was elected to the United States Congress in 1832. He was 49. The anti-Masonic movements collapsed in the next few years, but most of its supporters turned to the anti-slavery Liberty Party, which eventually merged with the Free Soil Party. Then was William's association with the abolitionists, which would eventually lead to the Jackson Homestead being used as an Underground Railroad stop. After a few years of moving to Newton, the candle factory became too much for William to manage, and he handed it over to his son, Timothy, and his nephew, Otis Trowbridge.

Another result of the Newton Temperance Movement was the Newton Savings Bank, later to become the National Savings Bank, designed to help men save money as an alternative to spending it on liquor. William Jackson was its first president from its founding in 1848 until his death. William participated in a full range of town committees, meetings, and activities, especially education and religion. He was deeply religious at this point, although he had not been throughout his childhood, teens, and young adulthood. William ended up being active in the Sabbath Schools, Deacon of the First Church, and Deacon of the Eliot Church, which he helped to found, as an end to a full and prosperous career.

Mary (Bennett) Jackson

After William's death in 1855, Mary remained in the house with her three unmarried daughters, Ellen, Caroline, and Cornelia. They managed to keep the Homestead going by taking in various boarders, who most likely lodged in the garret and the eastern chambers, and by earning money as best they could. Mary was in poor health throughout her life, being a frail woman with a tendency to get chilled, but she bore William twelve children over twenty years, did many good deeds and acts of charity, and was remembered by her descendants as a warm and welcoming mother and grandmother.

Ellen, Caroline, and Cornelia Jackson

After their mother's death, the three sisters took over the homestead.

The Jackson Homestead and Museum

Today, the Jackson Homestead is a museum known as the Jackson Homestead and Museum. It is part of Historic Newton,[4] whose mission is to "inspire discovery and engagement by illuminating our community’s stories within the context of American history".[5] The Jackson Homestead and Museum displays rotating and permanent exhibits about the history of Newton, Massachusetts, and the Underground Railroad.[6] The Homestead is also home to the archives of Historic Newton.

The museum is open to the public Wednesday-Friday: 11:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. and Saturday and Sunday: 10:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. The museum is closed Mondays, Tuesdays, and major holidays.

On June 4, 1973, the Jackson Homestead was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

See also

- Francis Jackson (abolitionist)

- William Jackson (Massachusetts)

- List of Underground Railroad sites

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Newton, Massachusetts

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Aboard the Underground Railroad: Jackson Homestead

- 1 2 http://www.ci.newton.ma.us/jackson/pdf-files/jackson-homestead.pdf

- ↑ http://www.newtonma.gov/gov/historic/default.asp

- ↑ http://www.newtonma.gov/gov/historic/about/mission.asp

- ↑ http://www.newtonma.gov/gov/historic/visit/jackson_homestead_and_museum/default.asp