Jack and the Beanstalk

| Jack and the Beanstalk | |

|---|---|

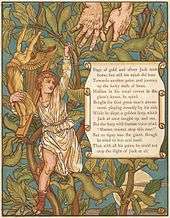

Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1918, in English Fairy Tales by Flora Annie Steel | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Jack and the Beanstalk |

| Also known as | Jack and the Giant man |

| Data | |

| Aarne-Thompson grouping | AT 328 ("The Treasures of the Giant") |

| Country | England |

| Published in |

Benjamin Tabart, The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk (1807) Joseph Jacobs, English Fairy Tales (1890) |

| Related | Jack the Giant Killer |

"Jack and the Beanstalk" is an English fairy tale. It appeared as "The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean" in 1734[1] and as Benjamin Tabart's moralised "The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk" in 1807.[2] Henry Cole, publishing under pen name Felix Summerly popularised the tale in The Home Treasury (1845),[3] and Joseph Jacobs rewrote it in English Fairy Tales (1890).[4] Jacobs' version is most commonly reprinted today and it is believed to be closer to the oral versions than Tabart's because it lacks the moralising.[5]

"Jack and the Beanstalk" is the best known of the "Jack tales", a series of stories featuring the archetypal Cornish and English hero and stock character Jack.[6]

According to researchers at the universities in Durham and Lisbon, the story originated more than 5,000 years ago, based on a widespread archaic story form which is now classified by folkorists as ATU 328 The Boy Who Stole Ogre's Treasure.[7]

Story

Jack is a young, poor boy living with his widowed mother and a dairy cow, on a farm cottage, the cow's milk was their only source of income. When the cow stops giving milk, Jack's mother tells him to take her to the market to be sold. On the way, Jack meets a bean dealer who offers magic beans in exchange for the cow, and Jack makes the trade. When he arrives home without any money, his mother becomes angry and disenchanted, throws the beans on the ground, and sends Jack to bed without dinner.

During the night, the magic beans cause a gigantic beanstalk to grow outside Jack's window. The next morning, Jack climbs the beanstalk to a land high in the sky. He finds an enormous castle and sneaks in. Soon after, the castle's owner, a giant, returns home. He senses that Jack is nearby by smell, and speaks a rhyme:

- Fee-fi-fo-fum!

- I smell the blood of an English man:

- Be he alive, or be he dead,

- I'll grind his bones to make my bread.

In the versions in which the giant's wife (the giantess) features, she persuades him that he is mistaken. When the giant falls asleep. Jack steals a bag of gold coins and makes his escape down the beanstalk.

Jack climbs the beanstalk twice more. He learns of other treasures and steals them when the giant sleeps: first a goose that lays golden eggs, then a magic harp that plays by itself. The giant wakes when Jack leaves the house with the harp and chases Jack down the beanstalk. Jack calls to his mother for an axe and before the giant reaches the ground, cuts down the beanstalk, causing the giant to fall to his death.

Jack and his mother live happily ever after with the riches that Jack acquired.

Origins

"The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean" was published in the 1734 second edition of Round About Our Coal-Fire.[1] In 1807, Benjamin Tabart published The History of Jack and the Bean Stalk, but the story is certainly older than these accounts. According to researchers at Durham University and the Universidade Nova de Lisboa, the story originated more than 5,000 years ago.[7]

In some versions of the tale, the giant is unnamed, but many plays based on it name him Blunderbore. (One giant of that name appears in the 18th-century "Jack the Giant Killer".) In "The Story of Jack Spriggins" the giant is named Gogmagog.

The giant's cry "Fee! Fie! Foe! Fum! I smell the blood of an Englishman" appears in William Shakespeare's early-17th-century King Lear in the form "Fie, foh, and fum, I smell the blood of a British man." (Act 3, Scene 4),[8] and something similar also appears in "Jack the Giant Killer".

Analogies

"Jack and the Beanstalk" is an Aarne-Thompson tale-type 328, The Treasures of the Giant, which includes the Italian "Thirteenth" and the French "How the Dragon was Tricked" tales. Christine Goldberg argues that the Aarne–Thompson system is inadequate for the tale because the others do not include the beanstalk, which has analogies in other types[9] (a possible reference to the genre anomaly.)[10]

The Brothers Grimm drew an analogy between this tale and a German fairy tale, "The Devil With the Three Golden Hairs". The devil's mother or grandmother acts much like the giant's wife, a female figure protecting the child from the evil male figure.[11]

"Jack and the Beanstalk" is unusual in some versions in that the hero, although grown up, does not marry at the end but returns to his mother. In other versions he is said to have married a princess. This is found in few other tales, such as some variants of "Vasilisa the Beautiful".[12]

Controversy

The original story portrays a "hero" gaining the sympathy of a man's wife, hiding in his house, robbing, and finally killing him. In Tabart's moralised version, a fairy woman explains to Jack that the giant had robbed and killed his father justifying Jack's actions as retribution.[13] (Andrew Lang follows this version in the Red Fairy Book of 1890.)

Jacobs gave no justification because there was none in the version he had heard as a child and maintained that children know that robbery and murder are wrong without being told in a fairy tale, but did give a subtle retributive tone to it by making reference to the giant's previous meals of stolen oxen and young children.[14]

Many modern interpretations have followed Tabart and made the giant a villain, terrorising smaller folk and stealing from them, so that Jack becomes a legitimate protagonist. For example, the 1952 film starring Abbott and Costello the giant is blamed for poverty at the foot of the beanstalk, as he has been stealing food and wealth and the hen that lays golden eggs originally belonged to Jack's family. In other versions it is implied that the giant had stolen both the hen and the harp from Jack's father. Brian Henson's 2001 TV miniseries Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story not only abandons Tabart's additions but vilifies Jack, reflecting Jim Henson's disgust at Jack's unscrupulous actions.[15]

Film adaptations

- The first film adaptation was made in 1902 by Edwin S. Porter for the Edison Manufacturing Company.

- Walt Disney made a short of the same name in 1922, and a separate adaptation titled Mickey and the Beanstalk in 1947 as part of Fun and Fancy Free. This adaptation of the story put Mickey Mouse in the role of Jack, accompanied by Donald Duck, and Goofy. Mickey, Donald, and Goofy live on a farm in "Happy Valley", so called because it is always green and prosperous thanks to the magical singing from an enchanted golden harp in a castle, until one day it mysteriously disappears during a dark storm, resulting in the valley being plagued by a severe drought. Times become so hard for Mickey and his friends that soon they have nothing to eat except one loaf of bread. Mickey trades in the cow (which Donald was going to kill for food) for the magic beans. Donald throws the beans on the floor and down a knothole in a fit of rage, and the beanstalk sprouts that night, lifting the three of them into the sky while they sleep. In the magical kingdom, Mickey, Donald, and Goofy help themselves to a sumptuous feast. This rouses the ire of the giant (named "Willie" in this version), who captures Donald and Goofy and locks them in a box, and it is up to Mickey to find the keys to unlock the box and rescue them as well as the harp which they also find in the giant's possession. The film villainizes the giant by blaming Happy Valley's hard times on Willy's theft of the magic harp, without which song the land withers; unlike the harp of the original tale, this magic harp wants to be rescued from the giant, and the hapless heroes return her to her rightful place and Happy Valley to its former glory. This version of the fairy tale was narrated (as a segment of Fun and Fancy Free) by Edgar Bergen, and later (by itself as a short) by Sterling Holloway. Additionally, Walt Disney Animation Studios will do another adaptation of the fairy tale called Gigantic. Tangled director Nathan Greno will direct and it is set to be released in late 2020[16]

- Warner Bros. adapted the story into three Merrie Melodies cartoons. Friz Freleng directed Jack-Wabbit and the Beanstalk (1943), Chuck Jones directed Beanstalk Bunny (1955), and Freleng directed Tweety and the Beanstalk (1957).

- The 1952 Abbott and Costello adaptation was not the only time a comedy team was involved with the story. The Three Stooges had their own five-minute animated retelling, titled Three Jacks and a Beanstalk (1965).

- In 1967, Hanna-Barbera produced a live action version of Jack and the Beanstalk, with Gene Kelly as Jeremy the Peddler, Bobby Riha as Jack, Dick Beals as Jack's singing voice, Ted Cassidy as the voice of the giant, Janet Waldo as the voice of Princess Serena, and Marni Nixon as Serena's singing voice.[17] The film won an Emmy Award.[18]

- Gisaburo Sugii directed a feature-length anime telling of the story released in 1974, titled Jack to Mame no Ki. The film, a musical, was produced by Group TAC and released by Nippon Herald. The writers introduced a few new characters, including Jack's comic-relief dog, Crosby, and Margaret, a beautiful princess engaged to be married to the giant (named "Tulip" in this version) due to a spell being cast over her by the giant's mother (an evil witch called Madame Hecuba). Jack, however, develops a crush on Margaret, and one of his aims in returning to the magic kingdom is to rescue her. The film was dubbed into English, with legendary voice talent Billie Lou Watt voicing Jack, and received a very limited run in U.S. theaters in 1976. It was later released on VHS (now out of print) and aired several times on HBO in the 1980s. However, it is now available on DVD with both English and Japanese dialogue.

- Michael Davis directed the 1994 adaptation, titled Beanstalk, starring J. D. Daniels as Jack and Stuart Pankin as the giant. The film was released by Moonbeam Entertainment, the children's video division of Full Moon Entertainment.

- Wolves, Witches and Giants Episode 9 of Season 1, Jack and the Beanstalk, broadcast on 19 October 1995, has Jack's mother chop down the beanstalk and the giant plummet through the earth to Australia. The hen that Jack has stolen fails to lay any eggs and ends up "in the pot by Sunday", leaving Jack and his mother to live in reduced circumstances for the rest of their lives.

- The Jim Henson Company did a TV miniseries adaptation of the story as Jim Henson's Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story (directed by Brian Henson) which reveals that Jack's theft from the giant was completely unmotivated, with the giant Thunderdell (played by Bill Barretta) being a friendly, welcoming individual, and the giant's subsequent death was caused by Jack's mother cutting the beanstalk down rather than Jack himself. The film focuses on Jack's modern-day descendant Jack Robinson (played by Matthew Modine) who learns the truth after the discovery of the giant's bones and the last of the five magic beans, Jack subsequently returning the goose and harp to the giants' kingdom.

- An episode of Mickey Mouse Clubhouse called Donald and the Beanstalk, Donald Duck accidentally swapped his pet chicken with Willie the Giant for a handful of magic beans.

- Avalon Family Entertainment's film, titled Jack and the Beanstalk and released on home video April 20, 2010, is a low-budget live-action adaptation starring Christopher Lloyd, Chevy Chase, James Earl Jones, Gilbert Gottfried, Katey Sagal, Wallace Shawn and Chloë Grace Moretz. Jack is played by Colin Ford.

- The Warner Bros. film directed by Bryan Singer and starring Nicholas Hoult as Jack is titled Jack the Giant Slayer and was released in March 2013.[19] In this tale Jack climbs the beanstalk to save a princess.

- Warner Bros. Animation's direct-to-DVD film Tom and Jerry's Giant Adventure is set to be based on the fairy tale.[20]

- In the 2014 film Into the Woods, and the musical of the same name, one of the main characters, Jack (Daniel Huttlestone) climbs a beanstalk, much like in the original version. He acquires a golden harp, a goose that lays golden eggs, and several gold pieces. The story goes on as it does in the original fairy tale, but continues afterwards showing what happens after you get your happy ending. In this adaptation, the giant's vengeful wife (Frances de la Tour) attacks the kingdom to find and kill Jack as revenge for him murdering her husband where some characters were killed during her rampage. The giant's wife is eventually killed by the surviving characters in the story.

Other adaptations

- The story is the basis of the similarly titled traditional British pantomime, wherein the Giant is certainly a villain, Jack's mother the Dame, and Jack the Principal Boy.

- Jack of Jack and the Beanstalk is the protagonist of the comic book Jack of Fables, a spin-off of Fables, which also features other elements from the story, such as giant beanstalks and giants living in the clouds.

- Gilligan's Island did a adaptation/dream sequence in which Gilligan tries to take oranges from a giant Skipper and fails; (the part of the little Gilligan chased by the giant was played by Bob Denver's 7 year old son Patrick Denver)

- Roald Dahl rewrote the story in a more modern and gruesome way in his book Revolting Rhymes (1982), where Jack initially refuses to climb the beanstalk and his mother is thus eaten when she ascends to pick the golden leaves at the top, with Jack recovering the leaves himself after having a thorough wash so that the giant cannot smell him. The story of Jack and the Beanstalk is also referenced in Dahl's The BFG, in which the evil giants are all afraid of the "giant-killer" Jack, who is said to kill giants with his fearsome beanstalk (although none of the giants appear to know how Jack uses it against them, the context of a nightmare one of the giants has about Jack suggesting that they think he wields the beanstalk as a weapon).

- James Still published Jack and the Wonder Beans (1977, republished 1996) an Appalachian variation on the Jack and the Beanstalk tale. Jack trades his old cow to a gypsy for three beans that are guaranteed to feed him for his entire life. It has been adapted as a play for performance by children.[21]

- In 1973 the story was adapted, as The Goodies and the Beanstalk, by the BBC television series The Goodies.

- An arcade video game, Jack the Giantkiller, was released by Cinematronics in 1982 and is based on the story. Players control Jack, and must retrieve a series of treasures – a harp, a sack of gold coins, a golden goose and a princess – and eventually defeat the giant by chopping down the beanstalk.

- An episode of The Super Mario Bros. Super Show!, entitled "Mario and the Beanstalk", does a retelling with Bowser as the giant (there is no explanation as to how he becomes a giant).

- In The Magic School Bus episode "Gets Planted", the class put on a school production of Jack and the Beanstalk, with Phoebe starring as the beanstalk after Ms. Frizzle turned her into a bean plant.

- Jack and Beanstalk was featured in Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child where Jack is voiced by Wayne Collins and the giant is voiced by Tone Loc. The story is in an African-American style.

- Stephen Sondheim's musical Into the Woods (and the film of the same name), features Jack, originally portrayed by Ben Wright, along with several other fairy tale characters. In the second half of the musical, the giant's wife climbs down a second beanstalk to exact revenge for her husband's death, furious at Jack's betrayal of her hospitality. She is eventually killed as well.

- Bart Simpson plays the role of the main character in a Simpsons video game "The Simpsons: Bart & the Beanstalk".

- ABC's Once Upon a Time debuts their spin on the tale in the episode "Tiny" of season two, where Jack, now a female named Jacqueline (known as Jack) is played by Cassidy Freeman and the giant named Anton is played by Jorge Garcia. In this adaptation, Jack is portrayed as a villainous character.

- The story was adapted in 2012 by software maker Net Entertainment and made into a slot machine game.[22]

- Mark Knopfler sang a song, "After the Beanstalk", in his 2012 album Privateering.

- Snips, Snails, and Dragon Tails, an Order of the Stick print book, contains an adaptation in the Sticktales section. Elan is Jack, Roy is the giant, Belkar is the golden goose, and Vaarsuvius is the wizard who sells the beans. Haley also appears as an agent sent to steal the golden goose, and Durkin as a dwarf neighbor with the comic's stereotypical fear of tall plants.

- In the Season 3 premiere episode of Barney and Friends titled "Shawn and the Beanstalk", Barney the Dinosaur and the gang tell their version of Jack and the Beanstalk which was all told in rhyme.

- In the animated movie Puss in Boots, the classic theme appears again. The magic beans play a central role in that movie, culminating in the scene, in which Puss, Kitty and Humpty ride a magic beanstalk to find the giant's castle.

- In a Happy Tree Friends episode called "Dunce Upon a Time", there was a strong resemblance as Giggles played a Jack-like role and Lumpy played a giant-like role.

- The story appears in the 2017 commercial for the British breakfast cereal Weetabix, where the giant is scared off by an English boy who has had a bowl of Weetabix.[23]

See also

References

- 1 2 Round About Our Coal Fire, or Christmas Entertainments. J.Roberts. 1734. pp. 35–48. 4th edition On Commons

- ↑ Tabart, The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk. in 1807 introduces a new character, a fairy who explains the moral of the tale to Jack (Matthew Orville Grenby, "Tame fairies make good teachers: the popularity of early British fairy tales", The Lion and the Unicorn 30.1 (January 2006:1–24).

- ↑ In 1842 and 1844 Elizabeth Rigby, Lady Eastlake, reviewed children's books for the Quarterly Review (volumes 71 and 74), recommending a list of children's books, headed by "The House [sic] Treasury, by Felix Summerly, including The Traditional Nursery Songs of England, Beauty and the Beast, Jack and the Beanstalk, and other old friends, all charmingly done and beautifully illustrated." (noted by Geoffrey Summerfield, "The Making of The Home Treasury", Children's Literature 8 (1980:35–52).

- ↑ Joseph Jacobs (1890). English Fairy Tales. London: David Nutt. pp. 59–67, 233.

- ↑ Maria Tatar, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, p. 132. ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ↑ "The Folklore Tradition of Jack Tales". The Center for Children's Books. Graduate School of Library and Information Science University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. 15 Jan 2004. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- 1 2 BBC. "Fairy tale origins thousands of years old, researchers say". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Tatar, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, p. 136.

- ↑ Goldberg, Christine. "The composition of Jack and the beanstalk". Marvels and Tales. Retrieved 2011-05-28.

- ↑ D. L. Ashliman, ed. "Jack and the Beanstalk: eight versions of an English fairy tale (Aarne-Thompson-Uther type 328)". 2002–2010. Folklore and Mythology: Electronic Texts. University of Pittsburgh. 1996–2013.

- ↑ Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, "The Devil With the Three Golden Hairs", Grimm's Fairy Tales.

- ↑ Maria Tatar, Off with Their Heads! p. 199. ISBN 0-691-06943-3

- ↑ Tatar, Off with Their Heads! p. 198.

- ↑ Joseph Jacobs, Notes to "Jack and the Beanstalk", English Fairy Tales.

- ↑ Joe Nazzaro, "Back to the Beanstalk", Starlog Fantasy Worlds, February 2002, pp. 56–59.

- ↑ http://www.bleedingcool.com/2013/08/21/exclusive-lots-of-details-of-disneys-unannounced-animated-film-giants

- ↑ Jack and the Beanstalk (1967 TV Movie), Full Cast & Crew, imdb.com

- ↑ Barbera, Joseph (1994). My Life in "Toons": From Flatbush to Bedrock in Under a Century. Atlanta, GA: Turner Publishing. pp. 162–65. ISBN 1-57036-042-1.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1351685/

- ↑ "Tom and Jerry's Giant Adventure Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. April 25, 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-25.

- ↑ Jack and the wonder beans (Book, 1996). [WorldCat.org]. Retrieved on 2013-07-29.

- ↑ Jack and the Beanstalk Slots. [SlotsForMoney.com]. Retrieved on 2014-09-18.

- ↑ "Weetabix launches £10m campaign with Jack and the Beanstalk ad". Talking Retail. Retrieved 17 May 2017

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jack and the Beanstalk. |

- Slavic origin of Jack and the beanstalk hypothesis

- Pantomime based on the fairytale of "Jack and the Beanstalk"

- Jack and the Beanstalk Felt Story at Story Resources

- "Jack and the Beanstalk" at SurLaLune Fairy Tales — Annotated version of the fairy tale.

- Adult Pantomime based on the fairytale of "Jack and the Beanstalk"

- Jack tales in Appalachia — including "Jack and the Bean Tree"

- Children's audio story of Jack and the Beanstalk at Storynory

- Kamishibai (Japanese storycard) version — in English, with downloadable Japanese translation

- The Disney version of Jack and the Beanstalk at The Encyclopedia of Disney Animated Shorts

- Full text of Jack And The Bean-Stalk from "The Fairy Book"

- Jack et le Haricot Magique - The Rock Musical by Georges Dupuis & Philippe Manca

- Jack And The Beanstalk - Animation movie in 4K at Geetanjali Audios in collaboration with Film Art Music Entertainment Productions FAME Productions