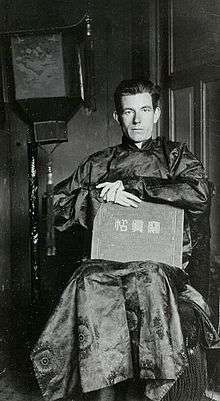

J. Slauerhoff

| J. Slauerhoff | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Jan Jacob Slauerhoff 15 September 1898 Leeuwarden, Netherlands |

| Died |

5 October 1936 (aged 38) Hilversum, Netherlands |

| Pen name | John Ravenswood (only occasionally) |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, general practitioner, ship's doctor |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Education | Medicine |

| Alma mater | Amsterdam Municipal University |

| Period | 1918–36 |

| Notable works | Soleares (poetry), The Forbidden Kingdom (prose) |

| Notable awards |

C.W. van der Hoogtprijs 1934 for Soleares |

| Spouse | Darja Collin (1930–1935) |

| Children | 1 (stillborn) |

Jan Jacob Slauerhoff (1898–1936), who published as J. Slauerhoff, was a Dutch poet and novelist. He is considered one of the most important Dutch language writers.

Youth

Slauerhoff was born fifth in a family of six children and raised in a moderately orthodox-protestant middle class environment in Leeuwarden, Netherlands. He suffered from bouts of asthma, especially during his childhood years; to alleviate his condition, Slauerhoff stayed on the island of Vlieland a couple of times during the summer months with relatives of his mother's.

Slauerhoff attended HBS (secondary school) in Harlingen, where he first met fellow future writer Simon Vestdijk. In 1916, Slauerhoff moved to Amsterdam to read medicine. While at the university, he wrote his first poems; his debut as a poet was in the Communist magazine De Nieuwe Tijd. He edited the Amsterdam student magazine Propria Cures from 1919 to 1920.[1] In 1919, Slauerhoff became engaged to a Dutch language student, Truus de Ruyter. In 1921 he joined the staff of the literary magazine Het Getij and later that of De Vrije Bladen; in this period he became acquainted with poets Hendrik Marsman and Hendrik de Vries.[1]

He took a confrontative stance towards conventional student life, taking on a bohemian role modelled on his French symbolist poet heroes Baudelaire, Verlaine, Corbière, and Rimbaud.

Early career

His first collection of verse, Archipel ("Archipelago"), was published in 1923,[1] by which time he had broken off his engagement to De Ruyter because he felt he was not ready for long-time commitment. That same year, 1923, Slauerhoff graduated from university.

Having made few friends and quite a number of enemies while at university, he found it hard to get a proper medical position in the Netherlands and so decided to sign up as a ship's doctor for a Dutch East Indies shipping company. His weak constitution immediately started to trouble him. On his first voyage, he suffered from gastric bleeding and asthma attacks. Slauerhoff returned to the Netherlands and apprenticed for a while in a number of doctor's practices, including one in the Frisian village of Beetsterzwaag.

After co-running a practice for a few months with a dentist in Haarlem, he signed up with another shipping company, the Java-China-Japan Lijn, and sailed for the Far East again. Until the end of his contract, in 1927, he made many voyages to China, Hong Kong, and Japan.

In 1928, Slauerhoff switched to the Koninklijke Hollandsche Lloyd and made a number of voyages to Latin America. His health improved somewhat and his literary production increased to match: by 1930, six collections of verse and two short story collections had been published. Literary critic and friend of Slauerhoff, Eddy du Perron, is to be thanked for this steady production of publications. During 1929, when Slauerhoff stayed at the Du Perron Belgian family mansion for some months, Du Perron helped him to sort, correct, and edit many of his poems and stories.

Marriage, final years

From 1929 on, Slauerhoff stayed in the Netherlands more frequently. He was an assistant in the Utrecht University clinic for Dermatology and Venereal Diseases from 1929–1930. In September 1930, he married dancer and ballet teacher Darja Collin, the start of a short happy period in his life. By 1931, however, Slauerhoff had fallen ill again (influenza and pneumonia) and left for the Italian health resort of Merano to recuperate. His wife followed him in 1932, so that they might experience the birth of their first child together. The child, however, was stillborn, prompting a serious depression in Slauerhoff, yet another disillusion on top of his physical ailments.

Later in 1932, Slauerhoff went to sea again, signing up with the Holland-West-Afrikalijn. His general bad health continued to worry him, however, and he considered moving to Northern Africa, as this would benefit his health. In March 1934, he set up a doctor's practice in Tangier, then an international protectorate, but by October he had left again. His periods of illness grew longer, the symptoms grew more serious, and his relationship with Darja deteriorated.

His fame as a writer, meanwhile, spread. In 1932 he published Het verboden rijk ("The Forbidden Kingdom"), a partly historical, partly magical realist novel combining the life of a 20th-century European with that of Luís de Camões, the 16th-century Portuguese poet (author of sonnets and the epic The Lusiads) who spent part of his life in the Orient.[2] Despite not being translated into English until 2012,[3] it attracted attention from scholars publishing in English, Jane Fenoulhet, for instance, referring to it as an important modernist novel in 2001.[4] Both Het verboden rijk and the follow-up novel Het leven op aarde ("Life on Earth," 1934) were widely praised, and his 1933 verse collection Soleares was awarded the Van der Hoogt Prize.[2]

The year 1935 saw yet more sea voyages, but also his divorce from Darja Collin. In this period of his life, Slauerhoff fell out with many of his literary friends, among them Du Perron and Vestdijk. During his last voyage, to South Africa, he fell severely ill with malaria on top of his neglected tuberculosis and returned to Merano for yet more recuperation. But by this time, it was too late. Still ill, he returned to the Netherlands in 1936 to take up residence in a nursing home in Hilversum, where he died on 5 October, just after his 38th birthday and one month after the publication of his last collection of verse, Een eerlijk zeemansgraf ("An Honourable Seaman's Grave").

Style and themes

Though Slauerhoff writes in the time of expressionism, his poetry is, according to Garmt Stuiveling and G.J. van Bork, essentially romantic: strongly autobiographical, it evidences restlessness, imagination, and a longing for faraway places, expressed through an identification with tramps, discoverers, and pirates.[1]

Much of Slauerhoff's work is concerned with the poor and downtrodden; especially the poetry collections Archipel (1923), Eldorado (1928), Soleares (1933), and Een eerlijk zeemansgraf (1936). A performance of his play Jan Pietersz. Coen (1930), highly critical of Jan Pieterszoon Coen (seventeenth-century officer of the Dutch East India Company in Indonesia and two-term Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies), was prohibited by the mayor of Amsterdam in 1948.[2]

Posthumous editions

Two works in progress that were nearly finished at the time of Slauerhoff's death, the original novel De opstand van Guadalajara ("The Guadalajara Uprising") and the translation of Martín Luis Guzmán's novel In de schaduw van den leider ("In the Shadow of the Leader"), were published posthumously in 1937.

A Committee for the Preparation of Slauerhoff's Complete Works was put together and convened to compile his Complete Works. This Committee, which consisted of leading literary figures, among which a number of friends of Slauerhoff, included D.A.M. Binnendijk, Menno ter Braak, N.A. Donkersloot, J. Greshoff, Kees Lekkerkerker, Hendrik Marsman, Adriaan Roland Holst, and Constant van Wessem. Du Perron contributed a general outline for the ordering and grouping of the contents, but declined to participate further. Work progressed slowly and was further slowed down by the events of World War II. The first volume appeared in 1941, one year behind schedule, and the series of eight volumes was not completed until 1958. Two of the Committee's members, Ter Braak and Marsman, died at the start of the war and the publisher, Nijgh & Van Ditmar, lost faith halfway through the project, which resulted in the intended separate volume of critical apparatus being scrapped and the last volume, containing Slauerhoff's essays, being published independently by Lekkerkerker.

Lekkerkerker, ever the dedicated text researcher and caretaker of Slauerhoff's literary heritage, continued over the years to unearth and study Slauerhoff's manuscripts and uncollected publications, resulting in ever better and more complete versions of the Complete Poems and Complete Prose volumes, culminating in the 1980s in the publication of the definitive editions of Slauerhoff's prose.

Bibliography

English

- The Forbidden Kingdom. Transl. from the Dutch by Paul Vincent. London, Pushkin, 2012. ISBN 978-1-906548-88-9

Poetry

- Archipel ("Archipelago", 1923)

- Clair-obscur (1927)

- Oost-Azië ("East Asia", 1928, under ps. John Ravenswood)

- Eldorado (1928)

- Fleurs de marécage ("Marsh Flowers", 1929, in French)

- Saturnus ("Saturn", 1930, revised and enlarged re-issue of Clair-obscur)

- Yoeng Poe Tsjoeng ("Of Little Use", translations from the Chinese and original poems, 1930)

- Serenade (1930)

- Soleares (1933)

- Een eerlijk zeemansgraf ("An Honourable Seaman's Grave", 1936)

- Verzamelde gedichten ("Collected Verse", 1947)

- Al dwalend ("Wandering About", previously uncollected poems, 1947)

- Alleen in mijn gedichten kan ik wonen ("Only in My Poems Can I Dwell", anthology, 1978)

- Op aarde niet en niet op zee ("Not on earth, and not at sea"), poems selected by Henny Vrienten (Amsterdam: Nijgh & Van Ditmar 2000. ISBN 90-388-7039-6)

- In memoriam mijzelf ("In Memory of Myself", anthology, 2006)

Prose

Original prose

- Het Lente-eiland en andere verhalen ("The Isle of Spring and Other Stories", 1930, short stories)

- Schuim en asch ("Foam and Ashes", 1930, short stories)

- Het verboden rijk ("The Forbidden Kingdom", 1932, novel); translated into English by Paul Vincent (2012)

- Het leven op aarde ("Life on Earth", 1934, novel)

- De opstand van Guadalajara ("The Guadalajara Uprising", 1937, posthumously published novel)

- Verzameld proza ("Collected Prose", 1961)

- Verwonderd saam te zijn ("Strange Bedfellows", 1987, short stories and a one act play [1928–1935])

- Alleen de havens zijn ons trouw ("Only the Ports Are Loyal to Us", 1992, travelogue short stories [1927–1932])

Translated prose

- Ricardo Güiraldes — Don Segundo Sombra (1930, 1941², 1948³; from Spanish with R. Schreuder)

- José Maria de Eça de Queiroz — De misdaad van Pater Amaro ("Father Amaro's Crime", 1932; from Portuguese with R. Schreuder)

- Guillermo Hernández Mir — De hof der oranjeboomen ("The Court with the Orange Trees", 1932; from Spanish with R. Schreuder)

- Paulo Setúbal — Johan Maurits van Nassau ("John Maurice of Nassau", 1933; from Portuguese by R. Schreuder with J. Slauerhoff)

- Ramón Gómez de la Serna — Dokter hoe is het mogelijk ("Doctor Improbable", 1935; from Spanish)

- Martín Luis Guzmán — In de schaduw van den leider ("In the Shadow of the Leader", 1937; from Spanish with G.J. Geers, published posthumously)

- Jules Laforgue — Hamlet, of De gevolgen der kinderliefde ("Hamlet, or The Consequences of Filial Love", 1962, 1970²; from French [1928])

- Thomas Raucat — Twee verhalen ("Two Short Stories", 1974; from French [1929])

Drama

Miscellaneous

- Verzamelde werken ("Complete Works", 8 vols., 1941–1958)

- Brieven van Slauerhoff ("Letters from Slauerhoff", ed. by Arthur Lehning, 1955)

- Dagboek ("Diary", ed. by Kees Lekkerkerker, 1957)

- Verzameld Proza ("Collected Prose"), 2 vols. (The Hague: Nijgh & Van Ditmar 1975. ISBN 90-236-5569-9 (vol. 1) and ISBN 90-236-5570-2 (vol. 2))

- Slauerhoff student auteur ("Slauerhoff Student Writer", prose and poetry from Slauerhoff's student days ed. by Eep Francken et al., 1983)

- Brieven aan Hans Feriz ("Letters to Hans Feriz", ed. Herman Vernout, 1984)

- Het China van Slauerhoff: aantekeningen en ontwerpen voor de Cameron-romans ("Slauerhoff's China – Notes and Outlines for the Cameron Novels", ed. W. Blok et al., 1985)

- Hij droeg de zee en de verte aan zich mee ("He Carried the Sea and the Distance with Him", letters ed. by J.J. van Herpen, 1985)

- Cristina Branco Canta Slauerhoff (Cristina Branco Sings Slauerhoff, 9 poems translated into Portuguese and put to Fado music, 2000)

- Van een liefde die vriendschap bleef ("Of a Love that Remained Friendship", letters ed. by Wim Hazeu, 2007)

- Het heele leven is toch verloren ("Life Is a Lost Cause Anyway", poems, letters, diaries, ed. by Arie Pos et al.) ISBN 978-90-814450-7-8

Apart from the 2012 translation of Het verboden rijk by Paul Vincent, none of Slauerhoff's works have been translated into English yet, but there are a number of German, French, Italian, Ukrainian, and Portuguese translations of his prose works and Russian translations of his poetry.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Stuiveling, Garmt; Bork, G.J. van (1985). "Slauerhoff, Jan Jacob". In G.J. van Bork, P.J. Verkruijsse. De Nederlandse en Vlaamse auteurs van middeleeuwen tot heden met inbegrip van de Friese auteurs (in Dutch). Weesp: De Haan. pp. 529–30.

- 1 2 3 Laan, K. ter (1952). "J. Slauerhoff". Letterkundig woordenboek voor Noord en Zuid (in Dutch). The Hague/Jakarta: G.B. van Goor Zonen.

- ↑ Slauerhoff, Jacob (2012). The Forbidden Kingdom. London: Pushkin Press.

- ↑ Fenoulhet, Jane (2001). "Time Travel in the Forbidden Realm: J. J. Slauerhoff's Het verboden rijk Viewed as a Modernist Novel". Modern Language Review. 96 (2): 116–29. JSTOR 3735720. doi:10.2307/3735720.

- ↑ Veenstra, J.H.W. (1969). "Slauerhoff, Coen en de oorlogsmisdaden". Maatstaf. 17: 337–50. ISSN 0464-2198.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to J. Slauerhoff. |

- Texts and secondary literature at DBNL

- No Home English translation of Slauerhoff's Woninglooze.