Italian cruiser Calabria

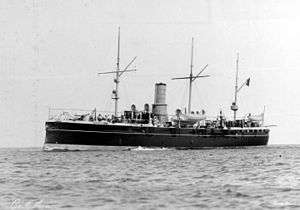

Calabria photographed soon after completion | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Builder: | La Spezia |

| Laid down: | February 1892 |

| Launched: | 20 September 1894 |

| Commissioned: | 12 July 1897 |

| Fate: | Sold for scrapping, 13 November 1924 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 2,660 t (2,620 long tons; 2,930 short tons) |

| Length: | 81 m (266 ft) |

| Beam: | 12.71 m (41.7 ft) |

| Draft: | 5.05 m (16.6 ft) |

| Installed power: | 4 water-tube boilers, 4,260 ihp (3,180 kW) |

| Propulsion: | Vertical triple-expansion engines |

| Speed: | 16.4 knots (30.4 km/h; 18.9 mph) |

| Range: | 2,500 nmi (4,600 km; 2,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 14–254 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: |

|

Calabria was a small protected cruiser built for the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy) in the 1890s, intended for service in Italy's overseas empire. She was laid down in 1892, launched in 1894, and completed in 1897, and was armed with a main battery of four 15-centimeter (5.9 in) and four 12 cm (4.7 in) guns. Calabria spent significant periods abroad, ranging from deployments to Chinese, North American, and Australian waters, in addition to periods in Italy's East African empire. She saw action during the Italo-Turkish War in 1912 in the Red Sea, primarily bombarding Turkish ports in the area. Calabria was reclassified as a gunboat in 1921, reduced to a training ship in 1924, and sold for scrap at the end of the year.

Design

Calabria was designed by the Chief Engineer, Edoardo Masdea, and was intended for overseas service. She had a steel hull sheathed with wood and zinc to protect it from fouling during lengthy deployments abroad. The hull was 76 meters (249 ft) long between perpendiculars and 81 m (266 ft) long overall. It had a beam of 12.71 m (41.7 ft) and a draft of 5.05 m (16.6 ft). Her normal displacement was 2,453 metric tons (2,414 long tons; 2,704 short tons) but increased to 2,660 t (2,620 long tons; 2,930 short tons) at full load. Calabria had a crew of between 214 and 254 officers and enlisted crew.[1][2]

The cruiser was powered by two-shaft vertical triple-expansion engines with steam supplied by four coal-fired, cylindrical water-tube boilers that were trunked into a single funnel amidships. The engines had an output of 4,260 indicated horsepower (3,180 kW) and produced a top speed of 16.4 knots (30.4 km/h; 18.9 mph). Calabria had a cruising radius of about 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 km; 2,900 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[1][2]

Calabria was armed with a main battery of four 15 cm (5.9 in) L/40 guns and four 12 cm (4.7 in) L/40 guns, all mounted individually.[Note 1] Light armaments included eight 5.7 cm (2.2 in) L/40 guns, eight 3.7 cm (1.5 in) L/20 guns, and a pair of machine guns. She was also equipped with a pair of 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes. Armor protection consisted of a 50 mm (2.0 in) thick deck; her conning tower also received 50 mm of steel plating.[1]

Service history

.jpg)

Calabria was built at the La Spezia dockyard, with her keel being laid down in February 1892. She was launched on 20 September 1894, and fitting-out work was completed by mid-1897; the new cruiser was commissioned into the Regia Marina (Royal Navy) on 12 July.[1] Calabria spent long periods abroad in her first decade of service. She was operating in Chinese waters in 1899 when the Boxer Rebellion broke out. She joined an international fleet that included representatives from the fleets of the Eight Nation Alliance in the mouth of the Hai River while a contingent of 475 soldiers traveled to Beijing to reinforce the Legation Quarter.[3]

The ship was present on 20 May 1902 when the United States formally granted independence to the Republic of Cuba, following the Spanish–American War three years earlier. Calabria and the British cruiser HMS Psyche fired salutes to the United States cruiser USS Brooklyn.[4] In March 1905 Calabria went on another cruise to American waters, this time to Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic. The visit represented an attempt at gunboat diplomacy, aimed at securing payments for debts to Italian nationals.[5] Later in the year, Calabria visited Australia on a trip to show the flag.[6] In October 1909, Calabria took part in the Portola Festival in San Francisco, marking the 140th anniversary of the Portolà expedition, the first recorded European exploration of what became California.[7]

Italo-Turkish War

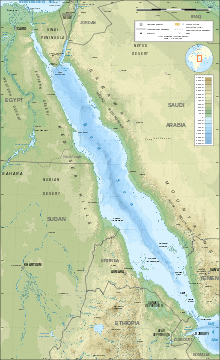

At the outbreak of the Italo-Turkish War in September 1911, Calabria was stationed in the Far East,[8] but she was immediately recalled to reinforce the Italian colony of Eritrea. After arriving in East African waters, she joined the cruiser Puglia in bombarding the Turkish port of Aqaba on 19 November to disperse a contingent of Ottoman soldiers there. Hostilities were temporarily ceased while the British King George V passed through the Red Sea following his coronation ceremony in India—the ceasefire lasted until 26 November. Four days later, Calabria and the gunboat Volturno attacked a quarantine station near Perim.[9]

In early 1912, the Italian Red Sea Fleet searched for a group of seven Ottoman gunboats thought to be planning an attack on Eritrea, though they were in fact immobilized due to a lack of coal. Calabria and the Puglia carried out diversionary bombardments against Jebl Tahr, and Al Luḩayyah, while the cruiser Piemonte and the destroyers Artigliere and Garibaldino searched for the gunboats. On 7 January, they found the gunboats and quickly sank four in the Battle of Kunfuda Bay; the other three were forced to beach to avoid sinking as well.[10][11] The next day, the Italian warships sent a shore party to destroy the grounded gunboats.[12] Calabria and the rest of the Italian ships returned to bombarding the Turkish ports in the Red Sea before declaring a blockade of the city of Al Hudaydah on 26 January.[11] Calabria returned to Italy by April for refitting.[13] The Ottomans eventually agreed to surrender in October, ending the war.[14]

Later career

In 1914, her armament was reduced; the 15 cm guns were removed and two additional 12 cm guns were installed in their place. Two of the 5.7 cm guns and six of the 3.7 cm guns were also removed.[1] The ship took a diplomatic mission from Massawa across the Red Sea to visit Hussein bin Ali, the recently-proclaimed King of Hejaz, in Mecca in July 1917.[15] Calabria returned to East African waters in January 1918 on another mission to show the flag, particularly off the coast of Somalia. Stops included Aden and Djibouti.[16] Calabria was reclassified as a gunboat in 1921, and she saw her armament modified again; a 15 cm gun was reinstalled, as were two of the 5.7 cm guns. A 4 cm (1.6 in) L/39 autocannon was also added at this time. She served in this role for only a short time, and was reduced to a training ship for naval gunners in early 1924.[17] This duty ended quickly, and she was sold for scrap on 13 November 1924.[1]

Footnotes

- Notes

- Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gardiner, p. 350

- 1 2 "Italy", p. 46

- ↑ Journal of the RUSI, p. 624

- ↑ Annual Report, p. 4

- ↑ Foreign Relations, p. 355

- ↑ Cresciani, p. 52

- ↑ "Italy's Cruiser Calabria here for Festival". San Francisco Call. 14 October 1909. p. 3. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ Beehler, p. 11

- ↑ Beehler, p. 48

- ↑ Hythe 1912, pp. 166–167.

- 1 2 Beehler, p. 51

- ↑ Willmott, p. 166

- ↑ Beehler, p. 70

- ↑ Beehler, p. 95

- ↑ Peters, p. 328

- ↑ Koburger, p. 14

- ↑ Gardiner & Gray, p. 257

References

- Annual Report of the Navy Department. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. 1902. OCLC 2480810. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Beehler, William Henry (1913). The History of the Italian-Turkish War: September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 1408563.

- Cresciani, Gianfranco (2003). The Italians in Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521537789.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal, eds. (1984). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1922. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Hythe, Thomas, ed. (1912). "The Naval Annual". Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

- "Italy". Notes on the Year's Naval Progress. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office: 45–48. 1895. OCLC 8098552.

- Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. London: J. J. Keliher & Co. XLVII. 1903. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Koburger, Charles W. (1992). Naval Strategy East of Suez: The Role of Djibouti. New York: Praeger. ISBN 0275941167.

- Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. 1906. OCLC 878572235. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Peters, F. E. (1994). The Hajj: The Muslim Pilgrimage to Mecca and the Holy Places. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 069102619X.

- Willmott, H. P. (2009). The Last Century of Sea Power (Volume 1, From Port Arthur to Chanak, 1894–1922). Bloomington,: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35214-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Calabria (ship, 1894). |

- "Calabria: Ariete torpediniere". Italian Ministry of Defence.