This article about the development of themes in Italian Renaissance painting is an extension to the article Italian Renaissance painting, for which it provides additional pictures with commentary. The works encompassed are from Giotto in the early 14th century to Michelangelo's Last Judgement of the 1530s.

The themes that preoccupied painters of the Italian Renaissance were those of both subject matter and execution- what was painted and the style in which it was painted. The artist had far more freedom of both subject and style than did a Medieval painter. Certain characteristic elements of Renaissance painting evolved a great deal during the period. These include perspective, both in terms of how it was achieved and the effect to which it was applied, and realism, particularly in the depiction of humanity, either as symbolic, portrait or narrative element.

Themes

The Flagellation of Christ by Piero della Francesca (above) demonstrates in a single small work many of the themes of Italian Renaissance painting, both in terms of compositional elements and subject matter. Immediately apparent is Piero's mastery of perspective and light. The architectural elements, including the tiled floor which becomes more complex around the central action, combine to create two spaces. The inner space is lit by an unseen light source to which Jesus looks. Its exact location can be pinpointed mathematically by an analysis of the diffusion and the angle of the shadows on the coffered ceiling. The three figures who are standing outside are lit from a different angle, from both daylight and light reflected from the pavement and buildings.

The religious theme is tied to the present. The ruler is a portrait of the visiting Emperor of Byzantium.[1] Flagellation is also called "scourging". The term "scourge" was applied to the plague. Outside stand three men representing those who buried the body of Christ. The two older, Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathaea, are believed to be portraits of men who recently lost their sons, one of them to plague. The third man is the young disciple John, and is perhaps a portrait of one of the sons, or else represents both of them in a single idealised figure, coinciding with the manner in which Piero painted angels.

Elements of Renaissance painting

Renaissance painting differed from the painting of the Late Medieval period in its emphasis upon the close observation of nature, particularly with regards to human anatomy, and the application of scientific principles to the use of perspective and light.

Linear perspective

The pictures in the gallery below show the development of linear perspective in buildings and cityscapes.

- In Giotto's fresco, the building is like a stage set with one side open to the viewer.

- In Paolo Uccello's fresco, the townscape gives an impression of depth.

- Masaccio's Holy Trinity was painted with carefully calculated mathematical proportions, in which he was probably assisted by the architect Brunelleschi.

- Fra Angelico uses the simple motif of a small loggia accurately drafted to create an intimate space.

- Gentile Bellini has painted a vast space, the Piazza San Marco in Venice, in which the receding figures add to the sense of perspective.

- Leonardo da Vinci did detailed and measured drawings of the background Classical ruins preparatory to commencing the unfinished Adoration of the Magi.

- Domenico Ghirlandaio created an exceptionally complex and expansive setting on three levels, including a steeply descending ramp and a jutting wall. Elements of the landscape, such as the church on the right, are viewed partly through other structures.

- Raphael's design for Fire in the Borgo shows buildings around a small square in which the background events are highlighted by the perspective.

Landscape

The depiction of landscape was encouraged by the development of linear perspective and the inclusion of detailed landscapes in the background of many Early Netherlandish paintings of the 15th century. Also through this influence came an awareness of atmospheric perspective and the observation of the way distant things are affected by light.

- Giotto uses a few rocks to give the impression of a mountain setting.

- Paolo Uccello has created a detailed and surreal setting as a stage for many small scenes.

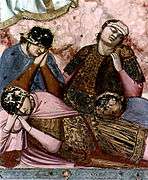

- In Carpaccio's Deposition of the Body of Christ, the desolate rocky landscape echoes the tragedy of the scene.

- Mantegna's landscape has a sculptural, three-dimensional quality that is suggestive of a real physical space. The details of the rocks, their strata and fractures, suggest that he studied the geological formations of the red limestone prevalent in areas of Northern Italy.

- Antonello da Messina sets the grim scene of the Crucifixion in contrast to the placid countryside which rolls into the far distance, becoming paler and bluer as it recedes.

- Giovanni Bellini has created a detailed landscape with a pastoral scene between the foreground and background mountains. There are numerous levels in this landscape, making it the equivalent of Ghirlandaio's complex cityscape (above).

- Perugino has set the Adoration of the Magi against the familiar hilly landscape of Umbria.

- Leonardo da Vinci, displays a theatrical use of atmospheric perspective in his view of the precipitous mountains around Lago di Garda at the foothills of the Alps in Northern Italy.

Light

Light and shade exist in a painting in two forms. Tone is simply the lightness and darkness of areas of a picture, graded from white to black. Tonal arrangement is a very significant feature of some paintings. Chiaroscuro is the modelling of apparent surfaces within a picture by the suggestion of light and shadow. While tone was an important feature of paintings of the Medieval period, chiaroscuro was not. It became increasingly important to painters of the 15th century, transforming the depiction of three-dimensional space.

- Taddeo Gaddi's Annunciation to the Shepherds is the first known large painting of a night scene. The internal light source of the picture is the angel.

- In Fra Angelico's painting, daylight, which appears to come from the actual window of the friary cell which this fresco adorns, gently illuminates the figures and defines the architecture.

- In his Emperor's Dream, Piero della Francesca takes up the theme of the night scene illuminated by an angel and applies his scientific knowledge of the diffusion of light. The tonal pattern thus created is a significant element in the composition of the painting.

- In his Agony in the Garden, Giovanni Bellini uses the fading sunset on a cloudy evening to create an atmosphere of tension and impending tragedy.

- In Domenico Veneziano's formal portrait, the use of chiaroscuro to model the form is slight. However, the painting relies strongly on the tonal contrasts of the pale face, mid-tone background and dark garment with patterned bodice for effect.

- Botticelli uses chiaroscuro to model the face of the sitter and define the details of his simple garment. The light and shadow on the edge of the window define the angle of the light.

- The suggested authorship of this early 16th century portrait includes Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, Mariotto Albertinelli and Giuliano Bugiardini. The painting combines many of the lighting effects of the other works in this gallery. The form is modelled by the light and shade, as if by a setting sun, which gives an element of drama, enhanced by the landscape. The tonal pattern created by the dark garment, the white linen and position of the hand is a compositional feature of the painting.

- In Leonardo da Vinci's John the Baptist, elements of the painting, including the corners of the model's eyes and mouth, are disguised by shadow, creating an air of ambiguity and mystery.

Anatomy

While remaining largely dependent upon topographic observation, the knowledge of anatomy was advanced by Leonardo da Vinci's meticulous dissection of 30 corpses. Leonardo, among others, impressed upon students the necessity of the close observation of life and made the drawing of live models an essential part of a student's formal study of the art of painting.

- Cimabue's Crucifixion, extensively destroyed by flood in 1966, shows the formal arrangement, with curving body and drooping head that was prevalent in late Medieval art. The anatomy is strongly stylised to conform with traditional iconic formula.

- Giotto abandoned the traditional formula and painted from observation.

- Massacio's figure of Christ is foreshortened as if viewed from below, and shows the upper torso strained as if with the effort of breathing.

- In Giovanni Bellini's Deposition the artist, while not attempting to suggest the brutal realities of the crucifixion, has attempted to give the impression of death.

- In Piero della Francesca's Baptism, the robust figure of Jesus is painted with a simplicity and lack of sharply defined muscularity that belies its naturalism.

- The figure of Jesus in this painting, which is the combined work of Verrocchio and the young Leonardo, has in all probability been drafted by Verrocchio. The contours retain the somewhat contorted linearity of Gothic art. Much of the torso, however, is thought to have been painted by Leonardo and reveals a strong knowledge of anatomical form.

- Leonardo's picture of St. Jerome shows the results of detailed study of the shoulder girdle, known from a page of drawings.

- Michelangelo used human anatomy to great expressive effect. He was renowned for his ability in the creation of expressive poses and was imitated by many other painters and sculptors.

| Cimabue. The Crucifix of Santa Croce, 1287 |

| Giotto, The Crucifix of Santa Maria Novella, c.1300 |

| Masaccio, Crucifixion of Santa Maria del Carmine ( Pisa), c. 1420 |

|

Realism

The observation of nature meant that set forms and symbolic gestures which in Medieval art, and particularly the Byzantine style prevalent in much of Italy, were used to convey meaning, were replaced by the representation of human emotion as displayed by a range of individuals.

- In this Resurrection, Giotto shows the sleeping soldiers with faces hidden by helmets or foreshortened to emphasise the relaxed posture.

- In contrast, Andrea Castagno has painted a life-sized image of the condotierre, Pippo Spano, alert and with his feet over the edge of the painted niche which frames him.

- Filippo Lippi in this early work shows a very naturalistic group of children crowding around the Virgin Mary, but looking with innocent curiosity at the viewer. One of the children has Down syndrome.

- Masaccio depicts the grief resulting from loss of innocence as Adam and Eve are expelled from the presence of God.

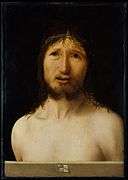

- Antonello da Messina painted several versions of Ecce Homo, the tormented Christ as he was presented to the people by the Roman Governor. Such paintings usually show Christ in a tragic but heroic role, minimising the depiction of suffering. Antonello's depictions are starkly realistic.

- In his Lamentation over the Dead christ, Mantegna has here depicted the dead body of Jesus with daring foreshortening, as if the viewer were standing at the end of the slab.

- In this detail from a larger painting, Mantegna shows a little child, wearing a tummy-binder and holey slippers, turning away and chewing its fingers while the infant Christ is circumcised.

- Giorgione paints a natural and unglamorised portrait of an old woman, unusual in its depiction of her illkempt hair and open mouth with crooked teeth.

| Mantegna, detail from the Circumcision of Christ. |

|

Among the preoccupations of artists commissioned to do large works with multiple figures were how to make the subject, usually narrative, easily read by the viewer, natural in appearance and well composed within the picture space.

- Giotto combines three separate narrative elements into this dramatic scene set against the dehumanising helmets of the guards. Judas betrays Jesus to the soldiers by kissing him. The High Priest signals to a guard to seize him. Peter slices the ear off the high priest's servant as he steps forward to lay hands on Jesus. Five figures dominate the foreground, surrounding Jesus so that only his head is visible. Yet by skilful arrangement of colour and the gestures of the men, Giotto makes the face of Jesus the focal point of the painting.

- In The Death of Adam, Piero della Francesca has set the dying patriarch so that he is cast into relief against the black garment worn by one of his family. His importance to the story is further emphasised by the arch of figures formed around him and the diagonals of the arms which all lead to his head.

- The Resurrection of the Son of Theophilus is a remarkably cohesive whole, considering that it was begun by Masaccio, left unfinished, vandalised, and eventually completed by Filippino Lippi. Masaccio painted the central section.

- Pollaiuolo, in this highly systemised painting, has taken the cross-bow used by the archers in the foreground, as the compositional structure. Within this large triangular shape, divided vertically, he has alternated the figures between front and back views.

- Botticelli's long, narrow painting of Mars and Venus is based on a W with the figures mirroring each other. The lovers, who shortly before were united, are now separated by sleep. The three small fawns who process across the painting hold the composition together.

- Michelangelos mastery of complex figure composition, as in his The Entombment was to inspire many artists for centuries. In this panel painting the figure of Christ, though vertical, is slumped and a dead weight at the centre of the picture, while those who try to carry the body lean outwards to support it.

- At first glance, Signorelli's Fall of the Damned is an appalling and violent jumble of bodies, but by the skilful placement of the figures so that the lines, rather than intersecting, flow in an undulating course through the picture, the composition is both unified and resolved into a large number of separate actions. The colours of the devils also serve to divide the picture into the tormentors and the tormented.

- The Battle of Ostia was executed by Raphael's assistants, probably to his design. The foreground of the painting is organised into two overlapping arched shapes, the larger showing captives being subdued, while to the left and slightly behind, they are forced to kneel before the Pope. While the Pope rises above the second group and dominates it, the first group is dominated by a soldier whose colour and splendid headdress acts like a visual stepping stone to the Pope. At the edges of this group two stooping figures mirror each other, creating a tension in which one pushes away from the edge of the painting and the other pulls upward at its centre.

Major works

Altarpieces

Through the Renaissance period, the large altarpiece had a unique status as a commission. An altarpiece was destined to become a focal point, not only visually in the religious building it occupied, but also in the devotions of the worshippers. Leonardo da Vinci's Madonna of the Rocks, now in the National Gallery, London but previously in a chapel in Milan, is one of many images that was used in the petitioning of the Blessed Virgin Mary against plague. The significance of these images to those who commissioned them, who worshipped in their location, and who created them is lost when they are viewed in an art gallery.

- The two Enthroned Madonnas by Cimabue and Duccio di Buoninsegna demonstrate the variations on a theme that was formalised and constrained by tradition. Although the positions of the Madonna and Child are very similar, the artists have treated most of the features differently. Cimabue's throne is front-on and uses perspective to suggest its solidity. The angels, their faces, wings and haloes, are arranged to form a rich pattern. The gold leaf detailing of the Madonna's garment picks out the folds in a delicate network. The Child sits regally, with his feet set at the same angle as his mother's.

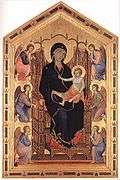

- In Duccio's Rucellai Madonna, the largest of its kind at 4.5 metres high, the throne is set diagonally and the Child, much more of a baby despite his gesture, sits diagonally opposed to his mother. While the positioning of the kneeling angels is quite simplistic, they have a naturalism in their repeated postures and are varied by the beautiful colour combinations of their robes. On the Madonna's robe the gold border makes a meandering line, defining the form and contours, and enlivening the whole composition with a single decorative detail.

- Giotto's Ognissanti Madonna is now housed in the same room of the Uffizi as Cimabue's and Duccio's, where the advances that he made in both drawing from the observation of nature, and in his use of perspective can be easily compared with the earlier masters. While the painting conforms to the model of an altarpiece, the figures within it do not follow the traditional formula. The Madonna and Child are solidly three-dimensional. This quality is enhanced by the canopied throne which contributes the main decorative element, while gold borders are minimised. The angels, which mirror each other, each have quite individual drapery.

- A hundred years later, Masaccio, still within the constraints of the formal altarpiece, confidently creates a three-dimensional figure draped in heavy robes, her chubby Christ Child sucking on his fingers. The lutes played by the little angels are both steeply foreshortened.

- In Fra Angelico's painting the figures lack the emphasis on mass of Masaccio's. Angelico was renowned for his delicacy in depicting the Madonna. The appeal of such paintings is demonstrated in the way the adoring angels are clustered around. As in Masaccio's painting, the Madonna's halo is decorated with pseudo-kufic script, probably to suggest her Middle Eastern origin.

- In the hands of Piero della Francesca the formal gold frame is transformed into a classical niche, drawn in perfect linear perspective and defined by daylight. The assorted saints cluster round in a natural way, while the Madonna sits on a realistic throne on a small podium covered by an oriental carpet, while the donor Federico da Montefeltro kneels at her feet. A concession to tradition is that the Madonna is of a larger scale than the other figures.

- In Bellini's painting, while on one hand, the figures and the setting give the effect of great realism, Bellini's interest in Byzantine icons is displayed in the hierarchical enthronement and demeanour of the Madonna.

- The Milanese painter Bergognone has drawn on aspects of the work of Mantegna and Bellini to create this painting in which the red robe and golden hair of Catherine of Alexandria are effectively balanced by the contrasting black and white of Catherine of Siena, and framed by a rustic arch of broken bricks.

- In Andrea Mantegna's Madonna della Vittoria, the Madonna may occupy the central position, framed in her garlanded gazebo, but the focus of attention is Francesco II Gonzaga whose achievements are acknowledged not only by the Madonna and Christ Child but by the heroic saints, Michael and George.

- Leonardo da Vinci abandoned any sort of formal canopy and surrounded the Madonna and Child with the grandeur of nature into which he set the figures in a carefully balanced yet seemingly informal trapezoid composition.

- The Sistine Madonna by Raphael uses the formula not of an altarpiece but the formal portrait, with a frame of green curtains through which a vision can be seen, witnessed by Pope Sixtus II for whom the work is named. The clouds around the Virgin are composed of cherubic faces, while the two iconic cherubs so beloved with the late 20th century fashion for angels, prop themselves on the sill. This work became the model for Murillo and many other painters.

- Andrea del Sarto, while using figures to a very natural and lifelike effect, abandons in the Madonna of the Harpies practical reality by setting the Madonna on a Classical plinth as if she were a statue. Every figure is in a state of instability, marked by the forward thrust of the Madonna's knee against which she balances a book. This painting is showing the trends that were to be developed in Mannerist painting.

| Cimabue, The Trinita Madonna, c.1280 |

|

| Raphael, The Sistine Madonna, 1513-14. |

|

Fresco cycles

The largest, most time-consuming paid work that an artist could do was a scheme of frescoes for a church, private palace or commune building. Of these, the largest unified scheme in Italy which remains more-or-less intact is that created by a number of different artists at the end of the Medieval period at the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi. It was followed by Giotto's Proto-Renaissance scheme at Padua and many others ranging from Benozzo Gozzoli's Magi Chapel for the Medici to Michelangelo's supreme accomplishment for Pope Julius II at the Sistine Chapel.

- Giotto painted the large, free-standing Scrovegni Chapel in Padua with the Life of the Virgin and the Life of Christ. Breaking from medieval tradition, it set a standard of naturalism.

- The two large frescoes of Allegories of Good and Bad Government painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti for the Commune of Siena are completely secular and show detailed views of a townscape with citizens, emphasising the importance of civic order.

- By contrast, Andrea di Bonaiuto, painting for the Dominicans at the new church of Santa Maria Novella, completed a huge fresco of the Triumph of the Church, which shows the role of the church in the work of Salvation, and in particular, the role of the Dominicans, who also appear symbolically as the Hounds of Heaven, shepherding the people of God. The painting includes a view of Florence Cathedral.

- Masaccio and Masolino collaborated on the Brancacci Chapel fresco cycle which is most famous for Masaccio's lifelike innovations, Masolino's more elegant style is seen in this townscape which skillfully combines two episodes of the Life of St. Peter.

- Piero della Francesca's fresco cycle in the church of San Francesco, Arezzo, closely follows the Legend of the True Cross as written by Jacopo da Varagine in the Golden Legend. The pictures reveal his studies of light and perspective, and the figures have an almost monolithic solidity.

- Benozzo Gozzoli's fresco cycle for the private chapel of the Medici Palace is a late work in the International Gothic style, a fanciful and richly ornamental depiction of the Medici with their entourage as the Three Wise Men.

- The elaborate cycle for the House of Este's Palazzo Schifanoia at Ferrara, executed in part by Francesco del Cossa, was also fanciful in its depictions of Classical deities and Zodial signs which are combined with scenes of the life of the family.

- Mantegna's paintings for the Gonzaga also show family life but have a preponderance of highly realistic elements and skillfully utilise the real architecture of the room they decorate, the mantelpiece forming a plinth for the figures and the real ceiling pendentives being apparently supported on painted pilasters.

- While in the Brancacci Chapel, historians seek to identify the faces of Masaccio, Masolino and perhaps Donatello among the apostles, Domenico Ghirlandaio at the Sassetti Chapel makes no attempt to disguise his models. Each fresco in this religious cycle has two sets of figures: those who tell the story and those who are witness to it. In this scene of the Birth of the Virgin Mary, a number of the noble women of Florence have come in, as if to congratulate the new mother.

- The Punishment of the Sons of Korah by Botticelli is one of episodes the Life of Moses series, which, together with The Life of Christ, was commissioned in the 1480s as decoration to the Sistine Chapel. The artists Perugino, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Cosimo Rosselli all worked on the carefully designed and harmonious scheme.

- Michelangelo's painting of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, which he executed alone over a period of five years, with narratives from Genesis, prophetic figures and the Ancestors of Christ, was destined to become one of the most famous artworks in the world.

- Simultaneously, Raphael and a number of his assistants painted the papal chambers known as Raphael Rooms. In The School of Athens Raphael depicts famous people of his day, including Leonardo, Michelangelo, Bramante and himself, as philosophers of ancient Athens.

Subjects

Devotional images of the Madonna and Child were produced in very large numbers, often for private clients. Scenes of the Life of Christ, the Life of the Virgin, or Lives of the Saints were also made in large numbers for churches, particularly scenes associated with the Nativity and the Passion of Christ. The Last Supper was commonly depicted in religious refectories.

During the Renaissance an increasing number of patrons had their likeness committed to posterity in paint. For this reason there exists a great number of Renaissance portraits for whom the name of the sitter is unknown. Wealthy private patrons commissioned artworks as decoration for their homes, of increasingly secular subject matter.

Devotional paintings

The Madonna

These small intimate pictures, which are now nearly all in museums, were most often done for private ownership, but might occasionally grace a small altar in a chapel.

- The Madonna adoring the Christ Child with two Angels has always been particularly popular on account of the expressive little boy angel supporting the Christ Child. Paintings of Filippo Lippi's such as this were to particularly influence Botticelli.

- Verrocchio separates the Madonna and Christ Child from the viewer by a stone sill, also used in many portraits. The rose and the cherries represent spiritual love and sacrificial love.

- Antonello da Messina's Madonna and Child is superficially very like that of Verrocchio, but it is much less formal and both the mother and the child appear to be moving rather than posing for the painter. The foreshortened elbow of the Child as he reaches for his mother's breast occurs in Raphael's work and can be seen in a different form in Michelangelo's Doni Tondo.

- The figures placed at opposing diagonals seen in this early Madonna and Child by Leonardo da Vinci was a compositional theme that was to recur in many of his works and be imitated by his pupils and by Raphael.

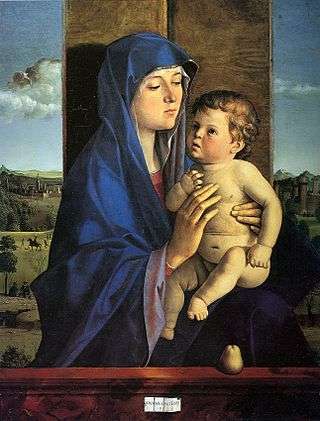

- Giovanni Bellini was influenced by Greek Orthodox icons. The gold cloth in this painting takes the place of the gold leaf background. The arrangement is formal, yet the gestures, and in particular the mother's adoring gaze, give a human warmth to this picture.

- Vittore Carpaccio's Madonna and Child is very unusual in showing the Christ Child as a toddler fully dressed in contemporary clothing. The meticulous detail and domesticity are suggestive of Early Netherlandish painting.

- Michelangelo's Doni Tondo is the largest of these works, but was a private commission. The highly unusual composition, the contorted form of the Madonna, the three heads all near the top of the painting and the radical foreshortening were all very challenging features, and Agnolo Doni was not sure that he wished to pay for it.

- Raphael has skillfully set opposing forces into play, and united the Madonna and Child with a loving gaze.

| Raphael, The Bridgewater Madonna, 1505. |

|

Secular paintings

Portraits

During the latter half of the 15th century, there was a proliferation of portraits. Although the subjects of some of them were later remembered for their achievements or their noble lineage, the identities of many have been lost and that of even the most famous portrait of all time, Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, is open to speculation and controversy.

- The advantage of a profile portrait such as Piero della Francesca's Portrait of Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta is that it identifies the subject like a facial signature. The proportions of the face, the respective angles of the forehead, nose and brow, the position and shape of the eye and the set of the jaw remain recognisable through life. Moreover, once a profile likeness has been taken, it can be used to cast a medal or sculpt an image in relief.

- Pollaiuolo has conformed to the formula, emphasising this young woman's profile with a fine line which also defines the delicate shape of her nostrils and the corners of her mouth. But he has added a three-dimensional quality by the subtle use of chiaroscuro and the treatment of the rich Florentine brocade of her sleeve.

- Alesso Baldovinetti, on the other hand, has used the profile of this strong-featured girl to create a striking pattern of a highlighted contour against the darker background. The background is a lively shape adding to the compositional structure of the painting. The little black fillet on her forehead responds to the dynamic pattern of the embroidered sleeve.

- Botticelli's portrait, although turned to three-quarter view with strong tonal modelling, has much to do with Baldovinetti's painting in its striking arrangement of shapes in the red garment, the hat and the dark hair and the pattern that they form against the background.

- Antonello da Messina's portrait, some years earlier than Botticelli's, bears it a passing similarity. But this painting does not rely heavily on the skilful arrangement of clearly contoured shapes. Antonello has used the advantages of oil paint, as against Botticelli's tempera, to achieve a subtle and detailed likeness in which the bushy eyebrows, the imperfections of the skin and the shadow of the beard have been rendered with photographic precision.

- Ghirlandaio's tempera portrait of an old man with his grandson combines the meticulous depiction of the old man's enlarged nose and parchment-like skin with a tenderness usually reserved for portrayals of The Madonna and Child. Ghirlandaio takes this analogy further by setting the scene against a window and landscape.

- Pintoricchio's portrait of a boy sets him high in the picture frame, reducing his scale in proportion to the area in contrast to the usual way of showing adults. The painting is set against a landscape such as used by Leonardo and Bellini. Pinturicchio's main fame lay in his skillfully characterised portraits like this.

- In the Mona Lisa Leonardo employed the technique of sfumato, delicately graded chiaroscuro that models the surface contours, while allowing details to disappear in the shadows. The technique gives an air of mystery to this painting which has brought it lasting fame. The beautiful hands become almost a decorative element.

- Giovanni Bellini's portrait of the elected Duke of Venice has an official air and could hardly be more formal. Yet the face is characterised with what one might hope for in the Doge, wisdom, humour and decisiveness. Although a more elaborate painting, it has much in common with Baldovinetti's sense of design.

- The subject of Titian's portrait is unknown, and its considerable fame rests solely on its beauty and unusual composition in which the face is supported and balanced by the large blue sleeve of quilted satin. The sleeve is almost the same colour as the background; its rich tonality gives it form. The white linen of the shirt enlivens the composition, while the man's eyes pick up the colour of the sleeve with penetrating luminosity.

- Superficially, Andrea del Sarto's portrait has many of the same elements as Titian's. But it is handled very differently, being much broader in treatment, and less compelling in subject. The painting has achieved an imediacy, as if the sitter has paused for a moment and is about to return to what he is doing.

- Raphael, in this much-copied portrait of Pope Julius II, set a standard for the painting of future popes. Unlike the contemporary portraits here by Bellini, Titian and del Sarto, Raphael has abandoned the placement of the figure behind a shelf or barrier and has shown the Pope as if seated in his own apartment. Against the green cloth decorated with the keys of St. Peter, the red velvet papal garments make a rich contrast, the white beard being offset by the pleated white linen. On the uprights of the chair, the acorn finials are the symbol of the Pope's family, the della Rovere.

| Botticelli, Portrait of Lorenzo di Ser Piero Lorenzi, 1490-95. |

|

| Titian, The Man with the blue sleeve, c.1510. |

|

The nude

These four famous paintings demonstrate the advent and acceptance of the nude as a subject for the artist in its own right.

- In Botticelli's Birth of Venus, the nude figure, although central to the painting, is not of itself the subject. The subject of the painting is a story from Classical mythology. The fact that the Goddess Venus rose naked from the sea provides justification for the nude study that dominates the centre of the work.

- Painted thirty years later, the exact meaning of Giovanni Bellini's picture is unclear. Had the subject been painted by an Impressionist painter, it would be quite unnecessary to ascribe a meaning. But in this Renaissance work, there is the presence of a mirror, an object that is usually symbolic and which suggests an allegory. The young lady's nakedness is a sign not so much of seduction, as innocence and vulnerability. However, she decks herself out in an extremely rich headdress, stitched with pearls, and having not one, but two mirrors, sees only herself reflected endlessly. The mirror, often a symbol of prophecy, here becomes an object of vanity, with the young woman in the role of Narcissus.

- Giorgione's painting possibly predates Bellini's by ten years. It has always been known as The Sleeping Venus but there is nothing in the painting to confirm that it is, indeed, Venus. The painting is remarkable for its lack of symbolism and the emphasis on the body simply as an object of beauty. It is believed to have been completed by Titian.

- Titian's Venus of Urbino, on the other hand, was painted for the pleasure of the Duke of Urbino, and as in Botticelli's Birth of Venus, painted for a member of the Medici family, the model looks directly at the viewer. The model may very well have been the mistress of the client. Venus of Urbino is not simply a body beautiful in its own right. She is an individual and highly seductive young woman, who is not in the nude state indicative of heavenly perfection, but is simply naked, having taken off her clothes but left on some of her jewellery.

Classical mythology

Paintings of classical mythology were invariably done for the important salons in the houses of private patrons. Botticelli's most famous works are for the Medici, Raphael painted Galatea for Agostino Chigi and Bellini's Feast of the Gods was, with several works by Titian, in the home of Alfonso I d'Este

- Pollaiuolo's Hercules and the Hydra typifies many paintings of mythological subjects which lent themselves to interpretation that was both Humanist and Christian. In this work good overcomes evil, and courage is glorified. The figure of Hercules has resonances with the Biblical character of Samson who also was renowned for his strength and slew a lion.

- In Botticelli's Pallas and the Centaur, Wisdom, personified by Athena, leads the cowering Centaur by the forelock, so learning and refinement are able to overcome brute instinct, which is the characteristic symbolised by the centaur.

- Raphael's Galatea, though Classical in origin, has a specifically Christian resonance that would have been recognised by those who were familiar with the story. It is about the nature of love. While all around her aspire to earthly love and succumb to the arrows shot by the trio of cupids, Galatea has chosen spiritual love and turns her eyes to Heaven.

- Three large works remain that were painted for a single room for the Este by Bellini and his successor Titian. Of these, Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne represents a moment in a narrative. The other two paintings are jolly drinking scenes with a number of narrative elements introduced in a minor way, in order that characters might be identifiable. This painting does not appear to have any higher allegorical sentiment attached to it. It appears to be simply a very naturalistic portrayal of a number of the ancient gods and their associates, eating, drinking and enjoying the party.

| Botticelli, Pallas Athena and the Centaur, c.1481. |

| Raphael, The Triumph of Galatea, 1511 |

|

See also

Sources

General

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, (1568), 1965 edition, trans George Bull, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-044164-6

- Frederick Hartt, A History of Italian Renaissance Art, (1970) Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-23136-2

- R.E. Wolf and R. Millen, Renaissance and Mannerist Art, (1968) Abrams, ISBN unknown

- Keith Chistiansen, Italian Painting, (1992) Hugh Lauter Levin/Macmillan, ISBN 0883639718

- Helen Gardner, Art through the Ages, (1970) Harcourt, Brace and World, ISBN 0-15-503752-8

- Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, (1974) Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-881329-5

- Margaret Aston, The Fifteenth Century, the Prospect of Europe, (1979) Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-33009-3

- Ilan Rachum, The Renaissance, an Illustrated Encyclopedia, (1979) Octopus, ISBN 0-7064-0857-8

- Diana Davies, Harrap's Illustrated Dictionary of Art and Artists, (1990) Harrap Books, ISBN 0-245-54692-8

- Luciano Berti, Florence: the city and its art, (1971) Scala, ISBN unknown

- Luciano Berti, The Ufizzi, (1971) Scala, Florence. ISBN unknown

- Michael Wilson, The National Gallery, London, (1977) Scala, ISBN 0-85097-257-4

- Hugh Ross Williamson, Lorenzo the Magnificent, (1974) Michael Joseph, ISBN 0-7181-1204-0

Painters

- John White, Duccio, (1979) Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-09135-8

- Cecilia Jannella, Duccio di Buoninsegna, (1991) Scala/Riverside, ISBN 1-878351-18-4

- Sarel Eimerl, The World of Giotto, (1967) Time/Life, ISBN 0-900658-15-0

- Mgr. Giovanni Foffani, Frescoes by Giusto de' Menabuoi, (1988) G. Deganello, ISBN unknown

- Ornella Casazza, Masaccio and the Brancacci Chapel, (1990) Scala/Riverside, ISBN 1-878351-11-7

- Annarita Paolieri, Paolo Uccello, Domenico Veneziano, Andrea del Castagno, (1991) Scala/Riverside, ISBN 1-878351-20-6

- Alessandro Angelini, Piero della Francesca, (1985) Scala/Riverside, ISBN 1-878351-04-4

- Peter Murray and Pier Luigi Vecchi, Piero della Francesca, (1967) Penguin, ISBN 0-14-008647-1

- Umberto Baldini, Primavera, (1984) Abrams, ISBN 0-8109-2314-9

- Ranieri Varese, Il Palazzo di Schifanoia, (1980) Specimen/Scala, ISBN unknown

- Angela Ottino della Chiesa, Leonardo da Vinci, (1967) Penguin, ISBN 0-14-008649-8

- Jack Wasserman, Leonardo da Vinci, (1975) Abrams, ISBN 0-8109-0262-1

- Massimo Giacometti, The Sistine Chapel, (1986) Harmony Books, ISBN 0-517-56274-X

- Ludwig Goldschieder, Michelangelo, (1962) Phaidon, ISBN unknown

- Gabriel Bartz and Eberhard König, Michelangelo, (1998) Könemann, ISBN 3-8290-0253-X

- David Thompson, Raphael, the Life and Legacy, (1983) BBC, ISBN 0-563-20149-5

- Jean-Pierre Cuzin, Raphael, his Life and Works, (1985) Chartwell, ISBN 0-89009-841-7

- Mariolina Olivari, Giovanni Bellini, (1990) Scala. ISBN unknown

- Cecil Gould, Titian, (1969) Hamlyn, ISBN unknown

References

.jpg)