Italian Renaissance painting

Italian Renaissance painting is the painting of the period beginning in the late 13th century and flourishing from the early 15th to late 16th centuries, occurring in the Italian peninsula, which was at that time divided into many political areas. The painters of Renaissance Italy, although often attached to particular courts and with loyalties to particular towns, nonetheless wandered the length and breadth of Italy, often occupying a diplomatic status and disseminating artistic and philosophical ideas.[1]

The city of Florence in Tuscany is renowned as the birthplace of the Renaissance, and in particular of Renaissance painting. A detailed background is given in the companion articles Renaissance and Renaissance architecture.

Italian Renaissance painting can be divided into four periods: the Proto-Renaissance (1300–1400), the Early Renaissance (1400–1475), the High Renaissance (1475–1525), and Mannerism (1525–1600). These dates are approximations rather than specific points because the lives of individual artists and their personal styles overlapped the different periods.

The Proto-Renaissance begins with the professional life of the painter Giotto and includes Taddeo Gaddi, Orcagna and Altichiero. The Early Renaissance was marked by the work of Masaccio, Fra Angelico, Paolo Uccello, Piero della Francesca and Verrocchio. The High Renaissance period was that of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian. The Mannerist period included Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo and Tintoretto. Mannerism is dealt with in a separate article.

Influences

The influences upon the development of Renaissance painting in Italy are those that also affected Philosophy, Literature, Architecture, Theology, Science, Government and other aspects of society. The following is a summary of points dealt with more fully in the main articles that are cited above.

Philosophy

A number of Classical texts, that had been lost to Western European scholars for centuries, became available. These included Philosophy, Poetry, Drama, Science, a thesis on the Arts and Early Christian Theology. The resulting interest in Humanist philosophy meant that man's relationship with humanity, the universe and with God was no longer the exclusive province of the Church. A revived interest in the Classics brought about the first archaeological study of Roman remains by the architect Brunelleschi and sculptor Donatello. The revival of a style of architecture based on classical precedents inspired a corresponding classicism in painting, which manifested itself as early as the 1420s in the paintings of Masaccio and Paolo Uccello.

Science and technology

Simultaneous with gaining access to the Classical texts, Europe gained access to advanced mathematics which had its provenance in the works of Byzantine and Islamic scholars. The advent of movable type printing in the 15th century meant that ideas could be disseminated easily, and an increasing number of books were written for a broad public. The development of oil paint and its introduction to Italy had lasting effects on the art of painting.

Society

The establishment of the Medici Bank and the subsequent trade it generated brought unprecedented wealth to a single Italian city, Florence. Cosimo de' Medici set a new standard for patronage of the arts, not associated with the church or monarchy. The serendipitous presence within the region of Florence of certain individuals of artistic genius, most notably Giotto, Masaccio, Brunelleschi, Piero della Francesca, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, formed an ethos that supported and encouraged many lesser artists to achieve work of extraordinary quality.[2] A similar heritage of artistic achievement occurred in Venice through the talented Bellini family, their influential inlaw Mantegna, Giorgione, Titian and Tintoretto.[2][3][4]

Themes

_01.jpg)

Much painting of the Renaissance period was commissioned by or for the Catholic Church. These works were often of large scale and were frequently cycles painted in fresco of the Life of Christ, the Life of the Virgin or the life of a saint, particularly St. Francis of Assisi. There were also many allegorical paintings on the theme of Salvation and the role of the Church in attaining it. Churches also commissioned altarpieces, which were painted in tempera on panel and later in oil on canvas. Apart from large altarpieces, small devotional pictures were produced in very large numbers, both for churches and for private individuals, the most common theme being the Madonna and Child.

Throughout the period, civic commissions were also important. Local government buildings were decorated with frescoes and other works both secular, such as Ambrogio Lorenzetti's The Allegory of Good and Bad Government, and religious, such as Simone Martini's fresco of the Maestà, in the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena.

Portraiture was uncommon in the 14th and early 15th centuries, mostly limited to civic commemorative pictures such as the equestrian portraits of Guidoriccio da Fogliano by Simone Martini, 1327, in Siena and, of the early 15th century, John Hawkwood by Uccello in Florence Cathedral and its companion portraying Niccolò da Tolentino by Andrea del Castagno.

During the 15th century portraiture became common, initially often formalised profile portraits but increasingly three-quarter face, bust-length portraits. Patrons of art works such as altarpieces and fresco cycles often were included in the scenes, a notable example being the inclusion of the Sassetti and Medici families in Domenico Ghirlandaio's cycle in the Sassetti Chapel. Portraiture was to become a major subject for High Renaissance painters such as Raphael and Titian and continue into the Mannerist period in works of artists such as Bronzino.

With the growth of Humanism, artists turned to Classical themes, particularly to fulfill commissions for the decoration of the homes of wealthy patrons, the best known being Botticelli's Birth of Venus for the Medici. Increasingly, Classical themes were also seen as providing suitable allegorical material for civic commissions. Humanism also influenced the manner in which religious themes were depicted, notably on Michelangelo's Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Other motifs were drawn from contemporary life, sometimes with allegorical meaning, some sometimes purely decorative. Incidents important to a particular family might be recorded like those in the Camera degli Sposi that Mantegna painted for the Gonzaga family at Mantua. Increasingly, still lifes and decorative scenes from life were painted, such as the Concert by Lorenzo Costa of about 1490.

Important events were often recorded or commemorated in paintings such as Uccello's Battle of San Romano, as were important local religious festivals. History and historic characters were often depicted in a way that reflected on current events or on the lives of current people. Portraits were often painted of contemporaries in the guise of characters from history or literature. The writings of Dante, Voragine's Golden Legend and Boccaccio's Decameron were important sources of themes.

In all these subjects, increasingly, and in the works of almost all painters, certain underlying painterly practices were being developed: the observation of nature, the study of anatomy, of light, and perspective.[2][3][5]

Proto-Renaissance painting

Traditions of 13th-century Tuscan painting

The art of the region of Tuscany in the late 13th century was dominated by two masters of the Byzantine style, Cimabue of Florence and Duccio of Siena. Their commissions were mostly religious paintings, several of them being very large altarpieces showing the Madonna and Child. These two painters, with their contemporaries, Guido of Siena, Coppo di Marcovaldo and the mysterious painter upon whose style the school may have been based, the so-called Master of St Bernardino, all worked in a manner that was highly formalised and dependent upon the ancient tradition of icon painting.[6] In these tempera paintings many of the details were rigidly fixed by the subject matter, the precise position of the hands of the Madonna and Christ Child, for example, being dictated by the nature of the blessing that the painting invoked upon the viewer. The angle of the Virgin's head and shoulders, the folds in her veil, and the lines with which her features were defined had all been repeated in countless such paintings. Cimabue and Duccio took steps in the direction of greater naturalism, as did their contemporary, Pietro Cavallini of Rome.[2]

Giotto

_adj.jpg)

Giotto, (1266–1337), by tradition a shepherd boy from the hills north of Florence, became Cimabue's apprentice and emerged as the most outstanding painter of his time.[7] Giotto, possibly influenced by Pietro Cavallini and other Roman painters, did not base the figures he painted upon any painterly tradition, but upon the observation of life. Unlike those of his Byzantine contemporaries, Giotto's figures are solidly three-dimensional; they stand squarely on the ground, have discernible anatomy and are clothed in garments with weight and structure. But more than anything, what set Giotto's figures apart from those of his contemporaries are their emotions. In the faces of Giotto's figures are joy, rage, despair, shame, spite and love. The cycle of frescoes of the Life of Christ and the Life of the Virgin that he painted in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua set a new standard for narrative pictures. His Ognissanti Madonna hangs in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, in the same room as Cimabue's Santa Trinita Madonna and Duccio's Ruccellai Madonna where the stylistic comparisons between the three can easily be made.[8] One of the features apparent in Giotto's work is his observation of naturalistic perspective. He is regarded as the herald of the Renaissance.[9]

Giotto's contemporaries

Giotto had a number of contemporaries who were either trained and influenced by him, or whose observation of nature had led them in a similar direction. Although several of Giotto's pupils assimilated the direction that his work had taken, none was to become as successful as he. Taddeo Gaddi achieved the first large painting of a night scene in an Annunciation to the Shepherds in the Baroncelli Chapel of the Church of Santa Croce, Florence.[2]

The paintings in the Upper Church of the Basilica of St. Francis, Assisi, are examples of naturalistic painting of the period, often ascribed to Giotto himself, but more probably the work of artists surrounding Pietro Cavallini.[9] A late painting by Cimabue in the Lower Church at Assisi, of the Madonna and St. Francis, also clearly shows greater naturalism than his panel paintings and the remains of his earlier frescoes in the upper church.

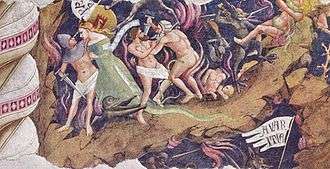

Mortality and redemption

A common theme in the decoration of Medieval churches was the Last Judgement, which in northern European churches frequently occupies a sculptural space above the west door, but in Italian churches such as Giotto's Scrovegni Chapel, is painted on the inner west wall. The Black Death of 1348 caused its survivors to focus on the need to approach death in a state of penitence and absolution. The inevitability of death, the rewards for the penitent and the penalties of sin were emphasised in a number of frescoes, remarkable for their grim depictions of suffering and their surreal images of the torments of Hell.

These include the Triumph of Death by Giotto's pupil Orcagna, now in a fragmentary state at the Museum of Santa Croce, and the Triumph of Death in the Camposanto Monumentale at Pisa by an unknown painter, perhaps Francesco Traini or Buonamico Buffalmacco who worked on the other three of a series of frescoes on the subject of Salvation. It is unknown exactly when these frescoes were begun but it is generally presumed they post-date 1348.[2]

Two important fresco painters were active in Padua in the late 14th century, Altichiero and Giusto de' Menabuoi. Giusto's masterpiece, the decoration of the Cathedral's Baptistery, follows the theme of humanity's Creation, Downfall and Salvation, also having a rare Apocalypse cycle in the small chancel. While the whole work is exceptional for its breadth, quality and intact state, the treatment of human emotion is conservative by comparison with that of Altichiero's Crucifixion at the Basilica of Sant'Antonio, also in Padua. Giusto's work relies on formalised gestures, where Altichiero relates the incidents surrounding Christ's death with great human drama and intensity.[10]

In Florence, at the Spanish Chapel of Santa Maria Novella, Andrea Bonaiuti was commissioned to emphasise the role of the Church in the redemptive process, and that of the Dominican Order in particular. His fresco Allegory of the Active and Triumphant Church is remarkable for its depiction of Florence Cathedral, complete with the dome which was not built until the following century.[2]

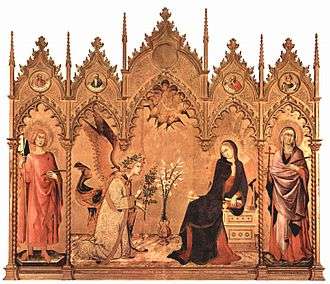

International Gothic

During the later 14th century, International Gothic was the style that dominated Tuscan painting. It can be seen to an extent in the work of Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, which is marked by a formalized sweetness and grace in the figures, and Late Gothic gracefulness in the draperies. The style is fully developed in the works of Simone Martini and Gentile da Fabriano, which have an elegance and a richness of detail, and an idealised quality not compatible with the starker realities of Giotto's paintings.[2]

In the early 15th century, bridging the gap between International Gothic and the Renaissance are the paintings of Fra Angelico, many of which, being altarpieces in tempera, show the Gothic love of elaboration, gold leaf and brilliant colour. It is in his frescoes at his convent of Sant' Marco that Fra Angelico shows himself the artistic disciple of Giotto. These devotional paintings, which adorn the cells and corridors inhabited by the friars, represent episodes from the life of Jesus, many of them being scenes of the Crucifixion. They are starkly simple, restrained in colour and intense in mood as the artist sought to make spiritual revelations a visual reality.[2][11]

Early Renaissance painting

Florence, 1401

The earliest truly Renaissance images in Florence date from the first year of the century known in Italian as Quattrocento, synonymous with the Early Renaissance. At that date a competition was held to find an artist to create a pair of bronze doors for the Baptistry of St. John, the oldest remaining church in the city. The Baptistry is a large octagonal building in the Romanesque style, whose origins had been forgotten and which was popularly believed to date from Roman times. The interior of its dome is decorated with an enormous mosaic figure of Christ in Majesty thought to have been designed by Coppo di Marcovaldo. It has three large portals, the central one being filled at that time by a set of doors created by Andrea Pisano eighty years earlier.

Pisano's doors were divided into 28 quatrefoil compartments, containing narratives scenes from the Life of John the Baptist. The competitors, of which there were seven young artists, were each to design a bronze panel of similar shape and size, representing the Sacrifice of Isaac.

Two of the panels have survived, that by Lorenzo Ghiberti and that by Brunelleschi. Each panel shows some strongly classicising motifs indicating the direction that art and philosophy were moving, at that time. Ghiberti has used the naked figure of Isaac to create a small sculpture in the Classical style. He kneels on a tomb decorated with acanthus scrolls that are also a reference to the art of Ancient Rome. In Brunelleschi's panel, one of the additional figures included in the scene is reminiscent of a well-known Roman bronze figure of a boy pulling a thorn from his foot. Brunelleschi's creation is challenging in its dynamic intensity. Less elegant than Ghiberti's, it is more about human drama and impending tragedy.[12]

Ghiberti won the competition. His first set of Baptistry doors took 27 years to complete, after which he was commissioned to make another. In the total of 50 years that Ghiberti worked on them, the doors provided a training ground for many of the artists of Florence. Being narrative in subject and employing not only skill in arranging figurative compositions but also the burgeoning skill of linear perspective, the doors were to have an enormous influence on the development of Florentine pictorial art. They were a unifying factor, a source of pride and camaraderie for both the city and its artists. Michelangelo was to call them the Gates of Paradise.

%2C_Masolino.jpg)

Brancacci Chapel

In 1426 two artists commenced painting a fresco cycle of the Life of St. Peter in the chapel of the Brancacci family, at the Carmelite Church in Florence. They both were called by the name of Tommaso and were nicknamed Masaccio and Masolino, Slovenly Tom and Little Tom.

More than any other artist, Masaccio recognized the implications in the work of Giotto. He carried forward the practice of painting from nature. His paintings demonstrate an understanding of anatomy, of foreshortening, of linear perspective, of light and the study of drapery. Among his works, the figures of Adam and Eve being expelled from Eden, painted on the side of the arch into the chapel, are renowned for their realistic depiction of the human form and of human emotion. They contrast with the gentle and pretty figures painted by Masolino on the opposite side of Adam and Eve receiving the forbidden fruit. The painting of the Brancacci Chapel was left incomplete when Masaccio died at 26. The work was later finished by Filippino Lippi. Masaccio's work became a source of inspiration to many later painters, including Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.[13]

Development of linear perspective

During the first half of the 15th century, the achieving of the effect of realistic space in a painting by the employment of linear perspective was a major preoccupation of many painters, as well as the architects Brunelleschi and Alberti who both theorised about the subject. Brunelleschi is known to have done a number of careful studies of the piazza and octagonal baptistery outside Florence Cathedral and it is thought he aided Masaccio in the creation of his famous trompe l'oeil niche around the Holy Trinity he painted at Santa Maria Novella.[13]

According to Vasari, Paolo Uccello was so obsessed with perspective that he thought of little else and experimented with it in many paintings, the best known being the three Battle of San Romano pictures which use broken weapons on the ground, and fields on the distant hills to give an impression of perspective.

In the 1450s Piero della Francesca, in paintings such as The Flagellation of Christ, demonstrated his mastery over linear perspective and also over the science of light. Another painting exists, a cityscape, by an unknown artist, perhaps Piero della Francesca, that demonstrates the sort of experiment that Brunelleschi had been making. From this time linear perspective was understood and regularly employed, such as by Perugino in his Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter in the Sistine Chapel.[12]

Understanding of light

Giotto used tonality to create form. Taddeo Gaddi in his nocturnal scene in the Baroncelli Chapel demonstrated how light could be used to create drama. Paolo Uccello, a hundred years later, experimented with the dramatic effect of light in some of his almost monochrome frescoes. He did a number of these in terra verde or "green earth", enlivening his compositions with touches of vermilion. The best known is his equestrian portrait of John Hawkwood on the wall of Florence Cathedral. Both here and on the four heads of prophets that he painted around the inner clockface in the cathedral, he used strongly contrasting tones, suggesting that each figure was being lit by a natural light source, as if the source was an actual window in the cathedral.[14]

Piero della Francesca carried his study of light further. In the Flagellation he demonstrates a knowledge of how light is proportionally disseminated from its point of origin. There are two sources of light in this painting, one internal to a building and the other external. Of the internal source, though the light itself is invisible, its position can be calculated with mathematical certainty. Leonardo da Vinci was to carry forward Piero's work on light.[15]

The Madonna

The Blessed Virgin Mary, revered by the Catholic Church worldwide, was particularly evoked in Florence, where there was a miraculous image of her on a column in the corn market and where both the Cathedral of "Our Lady of the Flowers" and the large Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella were named in her honour.

The miraculous image in the corn market was destroyed by fire, but replaced with a new image in the 1330s by Bernardo Daddi, set in an elaborately designed and lavishly wrought canopy by Orcagna. The open lower storey of the building was enclosed and dedicated as Orsanmichele.

Depictions of the Madonna and Child were a very popular art form in Florence. They took every shape from small mass-produced terracotta plaques to magnificent altarpieces such as those by Cimabue, Giotto and Masaccio.

In the 15th and first half of the 16th centuries, one workshop more than any other dominated the production of Madonnas. They were the della Robbia family, and they were not painters but modellers in clay. Luca della Robbia, famous for his cantoria gallery at the cathedral, was the first sculptor to use glazed terracotta for large sculptures. Many of the durable works of this family have survived. The skill of the della Robbias, particularly Andrea della Robbia, was to give great naturalism to the babies that they modelled as Jesus, and expressions of great piety and sweetness to the Madonna. They were to set a standard to be emulated by other artists of Florence.

Among those who painted devotional Madonnas during the Early Renaissance are Fra Angelico, Fra Filippo Lippi, Verrocchio and Davide Ghirlandaio. The custom was continued by Botticelli who produced a series of Madonnas over a period of twenty years for the Medici; Perugino, whose Madonnas and saints are known for their sweetness and Leonardo da Vinci, for whom a number of small attributed Madonnas such as the Benois Madonna have survived. Even Michelangelo who was primarily a sculptor, was persuaded to paint the Doni Tondo, while for Raphael, they are among his most popular and numerous works.

Early Renaissance painting in other parts of Italy

Andrea Mantegna in Padua and Mantua

One of the most influential painters of northern Italy was Andrea Mantegna of Padua, who had the good fortune to be in his teen years at the time in which the great Florentine sculptor Donatello was working there. Donatello created the enormous equestrian bronze, the first since the Roman Empire, of the condotiero Gattemelata, still visible on its plinth in the square outside the Basilica of Sant'Antonio. He also worked on the high altar and created a series of bronze panels in which he achieved a remarkable illusion of depth, with perspective in the architectural settings and apparent roundness of the human form all in very shallow relief.

At only 17 years old, Mantegna accepted his first commission, fresco cycles of the Lives of Saints James and Christopher for the Eremitani Chapel, near the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. Unfortunately the building was mostly destroyed during World War II, and they are only known from photographs which reveal an already highly developed sense of perspective and a knowledge of antiquity, for which the ancient University of Padua had become well known, early in the 15th century.[16] Mantegna's last work in Padua was a monumental San Zeno altarpiece, created for the abbot of the Basilica of San Zeno, Verona from 1457 to 1459.[17] This polyptych of which the predella panels are particularly notable for the handling of landscape elements, was to influence the further development of Renaissance art in Northern Italy[17] including artists of the school of Verona, Francesco Morone, Liberale da Verona and Girolamo dai Libri.[18]

Mantegna's most famous work is the interior decoration of the Camera degli Sposi for the Gonzaga family in Mantua, dated about 1470. The walls are frescoed with scenes of the life of the Gonzaga family, talking, greeting a younger son and his tutor on their return from Rome, preparing for a hunt and other such scenes that make no obvious reference to matters historic, literary, philosophic or religious. They are remarkable for simply being about family life. The one concession is the scattering of jolly winged cherubs who hold up plaques and garlands and clamber on the illusionistic pierced balustrade that surrounds a trompe l'oeil view of the sky that decks the ceiling of the chamber.[12]

Cosmè Tura in Ferrara

While Mantegna was working for the Gonzagas in Mantua, a very different painter was being employed to design an even more ambitious scheme for the Este family of Ferrara. Cosmè Tura's painting is highly distinctive, both strangely Gothic yet Classicising at the same time. Tura poses Classical figures as if they were saints, surrounds them with luminous symbolic motifs of surreal perfection and clothes them in garments that appear to be crafted out of intricately folded and enamelled copper.[12]

Borso d'Este's family had constructed a large banquetting hall and suite known as the Palazzo Schifanoia.[19] Borso, according to Tura's personal records, employed him in 1470 to design the decorative scheme for the banquetting hall, to be executed by Francesco del Cossa and Ercole de' Roberti.

The scheme is both symbolically complex and elaborate in execution. The overriding theme is the Cycle of the Year as represented by the signs of the zodiac accompanied by the mysterious Deans each ruling ten days of the month. Above them, seated in a spectacular array of chariots drawn by lions, eagles, unicorns and other such beasts, are twelve Roman deities with their various attributes. In the lower tiers, as in the Camera degli Sposi, are shown the life of the family. For the month of March, for example, the figure of Minerva, Goddess of Wisdom, is represented and in the panel beneath Borso d'Este is administering justice, while in the distance workers are pruning vines. Although areas of the frescoes are very badly damaged to the extent that the subject can no longer be identified, and although there are several different hands apparent in the works, there appears to be a consistency in the design of every remaining scene that shows the overriding eccentric style of Cosmè Tura.[20]

Antonello da Messina

In 1442 Alfonso V of Aragon became ruler of Naples, bringing with him a collection of Flemish paintings and setting up a Humanist Academy. The painter Antonello da Messina seems to have had access to the King's collection, which may have included the works of Jan van Eyck.[21] He seems to have been exposed to Flemish painting at a date earlier than the Florentines, to have quickly seen the potential of oils as a medium and then painted in nothing else. He carried the technique north to Venice with him, where it was soon adopted by Giovanni Bellini and became the favoured medium of the maritime republic where the art of fresco had never been a great success.

Antonello da Messina painted mostly small meticulous portraits in glowing colours. But one of his most famous works also demonstrates his superior ability at handling linear perspective and light. This is the small painting of St. Jerome in His Study, in which the composition is framed by a late Gothic arch, through which is viewed an interior, domestic on one side and ecclesiastic on the other, in the centre of which the saint sits in a wooden corral surrounded by his possessions while his lion prowls in the shadows on the tiled floor. The way the light streams in through every door and window casting both natural light and reflected light across the architecture and all the objects would have excited Piero della Francesca. Antonello's work influenced both Gentile Bellini, who did a series of paintings of Miracles of Venice for the Scuola di Santa Croce, and his more famous brother, Giovanni, one of the most significant painters of the High Renaissance in Northern Italy.[2][16]

High Renaissance

Patronage and Humanism

In Florence, in the later 15th century, most works of art, even those that were done as decoration for churches, were generally commissioned and paid for by private patrons. Much of the patronage came from the Medici family, or those who were closely associated with or related to them, such as the Sassetti, the Ruccellai and the Tornabuoni.

In the 1460s Cosimo de' Medici the Elder had established Marsilio Ficino as his resident Humanist philosopher, and facilitated his translation of Plato and his teaching of Platonic philosophy, which focused on humanity as the centre of the natural universe, on each person's personal relationship with God, and on fraternal or "platonic" love as being the closest that a person could get to emulating or understanding the love of God.[22]

In the Medieval period, everything related to the Classical period was perceived as associated with paganism. In the Renaissance it came increasingly to be associated with enlightenment. The figures of Classical mythology began to take on a new symbolic role in Christian art and in particular, the Goddess Venus took on a new discretion. Born fully formed, by a sort of miracle, she was the new Eve, symbol of innocent love, or even, by extension, a symbol of the Virgin Mary herself. We see Venus in both these roles in the two famous tempera paintings that Botticelli did in the 1480s for Cosimo's nephew, Pierfrancesco Medici, the Primavera and the Birth of Venus.[23]

Meanwhile, Domenico Ghirlandaio, a meticulous and accurate draughtsman and one of the finest portrait painters of his age, executed two cycles of frescoes for Medici associates in two of Florence's larger churches, the Sassetti Chapel at Santa Trinita and the Tornabuoni Chapel at Santa Maria Novella. In these cycles of the Life of St Francis and the Life of the Virgin Mary and Life of John the Baptist there was room for portraits of patrons and of the patrons' patrons. Thanks to Sassetti's patronage, there is a portrait of the man himself, with his employer, Lorenzo il Magnifico, and Lorenzo's three sons with their tutor, the Humanist poet and philosopher, Agnolo Poliziano. In the Tornabuoni Chapel is another portrait of Poliziano, accompanied by the other influential members of the Platonic Academy including Marsilio Ficino.[22]

Flemish influence

From about 1450, with the arrival in Italy of the Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden and possibly earlier, artists were introduced to the medium of oil paint. Whereas both tempera and fresco lent themselves to the depiction of pattern, neither presented a successful way to represent natural textures realistically. The highly flexibly medium of oils, which could be made opaque or transparent, and allowed alteration and additions for days after it had been laid down, opened a new world of possibility to Italian artists.

In 1475 a huge altarpiece of the Adoration of the Shepherds arrived in Florence. Painted by Hugo van der Goes at the behest of the Portinari family, it was shipped out from Bruges and installed in the Chapel of Sant' Egidio at the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova. The altarpiece glows with intense reds and greens, contrasting with the glossy black velvet robes of the Portinari donors. In the foreground is a still life of flowers in contrasting containers, one of glazed pottery and the other of glass. The glass vase alone was enough to excite attention. But the most influential aspect of the triptych was the extremely natural and lifelike quality of the three shepherds with stubbly beards, workworn hands and expressions ranging from adoration to wonder to incomprehension. Domenico Ghirlandaio promptly painted his own version, with a beautiful Italian Madonna in place of the long-faced Flemish one, and himself, gesturing theatrically, as one of the shepherds.[12]

Papal commission

In 1477 Pope Sixtus IV replaced the derelict old chapel at the Vatican in which many of the papal services were held. The interior of the new chapel, named the Sistine Chapel in his honour, appears to have been planned from the start to have a series of 16 large frescoes between its pilasters on the middle level, with a series of painted portraits of popes above them.

In 1480, a group of artists from Florence was commissioned with the work: Botticelli, Pietro Perugino, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Cosimo Rosselli. This fresco cycle was to depict Stories of the Life of Moses on one side of the chapel, and Stories of the Life of Christ on the other with the frescoes complementing each other in theme. The Nativity of Jesus and the Finding of Moses were adjacent on the wall behind the altar, with an altarpiece of the Assumption of the Virgin between them. These paintings, all by Perugino, were later destroyed to paint Michelangelo's Last Judgement.

.jpg)

The remaining 12 pictures indicate the virtuosity that these artists had attained, and the obvious cooperation between individuals who normally employed very different styles and skills. The paintings gave full range to their capabilities as they included a great number of figures of men, women and children and characters ranging from guiding angels to enraged Pharaohs and the devil himself. Each painting required a landscape. Because of the scale of the figures that the artists agreed upon, in each picture, the landscape and sky take up the whole upper half of the scene. Sometimes, as in Botticelli's scene of The Purification of the Leper, there are additional small narratives taking place in the landscape, in this case The Temptations of Christ.

Perugino's scene of Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter is remarkable for the clarity and simplicity of its composition, the beauty of the figurative painting, which includes a self-portrait among the onlookers, and especially the perspective cityscape which includes reference to Peter's ministry to Rome by the presence of two triumphal arches, and centrally placed an octagonal building that might be a Christian baptistry or a Roman Mausoleum.[24]

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo, because of the scope of his interests and the extraordinary degree of talent that he demonstrated in so many diverse areas, is regarded as the archetypal "Renaissance man". But it was first and foremost as a painter that he was admired within his own time, and as a painter, he drew on the knowledge that he gained from all his other interests.

Leonardo was a scientific observer. He learned by looking at things. He studied and drew the flowers of the fields, the eddies of the river, the form of the rocks and mountains, the way light reflected from foliage and sparkled in a jewel. In particular, he studied the human form, dissecting thirty or more unclaimed cadavers from a hospital in order to understand muscles and sinews.

More than any other artist, he advanced the study of "atmosphere". In his paintings such as the Mona Lisa and Virgin of the Rocks, he used light and shade with such subtlety that, for want of a better word, it became known as Leonardo's "sfumato" or "smoke".

Simultaneous to inviting the viewer into a mysterious world of shifting shadows, chaotic mountains and whirling torrents, Leonardo achieved a degree of realism in the expression of human emotion, prefigured by Giotto but unknown since Masaccio's Adam and Eve. Leonardo's Last Supper, painted in the refectory of a monastery in Milan, became the benchmark for religious narrative painting for the next half millennium. Many other Renaissance artists painted versions of the Last Supper, but only Leonardo's was destined to be reproduced countless times in wood, alabaster, plaster, lithograph, tapestry, crochet and table-carpets.

Apart from the direct impact of the works themselves, Leonardo's studies of light, anatomy, landscape, and human expression were disseminated in part through his generosity to a retinue of students.[7]

Michelangelo

In 1508 Pope Julius II succeeded in getting the sculptor Michelangelo to agree to continue the decorative scheme of the Sistine Chapel. The Sistine Chapel ceiling was constructed in such a way that there were twelve sloping pendentives supporting the vault that formed ideal surfaces on which to paint the Twelve Apostles. Michelangelo, who had yielded to the Pope's demands with little grace, soon devised an entirely different scheme, far more complex both in design and in iconography. The scale of the work, which he executed single handed except for manual assistance, was titanic and took nearly five years to complete.

The Pope's plan for the Apostles would thematically have formed a pictorial link between the Old Testament and New Testament narratives on the walls, and the popes in the gallery of portraits.[24] It is the twelve apostles, and their leader Peter as first Bishop of Rome, that make that bridge. But Michelangelo's scheme went the opposite direction. The theme of Michelangelo's ceiling is not God's grand plan for humanity's salvation. The theme is about humanity's disgrace. It is about why humanity needed, and in the terms of the faith, needs Jesus.[25]

Superficially, the ceiling is a Humanist construction. The figures are of superhuman dimension and, in the case of Adam, of such beauty that according to the biographer Vasari, it really looks as if God himself had designed the figure, rather than Michelangelo. But despite the beauty of the individual figures, Michelangelo has not glorified the human state, and he certainly has not presented the Humanist ideal of platonic love. In fact, the ancestors of Christ, which he painted around the upper section of the wall, demonstrate all the worst aspects of family relationships, displaying dysfunction in as many different forms as there are families.[25]

Vasari praised Michelangelo's seemingly infinite powers of invention in creating postures for the figures. Raphael, who was given a preview by Bramante after Michelangelo had downed his brush and stormed off to Bologna in a temper, painted at least two figures in imitation of Michelangelo's prophets, one at the church of Sant' Agostino and the other in the Vatican, his portrait of Michelangelo himself in The School of Athens.[24][26][27]

Raphael

With Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, Raphael's name is synonymous with the High Renaissance, although he was younger than Michelangelo by 18 years and Leonardo by almost 30. It cannot be said of him that he greatly advanced the state of painting as his two famous contemporaries did. Rather, his work was the culmination of all the developments of the High Renaissance.

Raphael had the good luck to be born the son of a painter, so his career path, unlike that of Michelangelo who was the son of minor nobility, was decided without a quarrel. Some years after his father's death he worked in the Umbrian workshop of Perugino, an excellent painter and a superb technician. His first signed and dated painting, executed at the age of 21, is the Betrothal of the Virgin, which immediately reveals its origins in Perugino's Christ giving the Keys to Peter.[16] Raphael was a carefree character who unashamedly drew on the skills of the renowned painters whose lifespans encompassed his. In his works the individual qualities of numerous different painters are drawn together. The rounded forms and luminous colours of Perugino, the lifelike portraiture of Ghirlandaio, the realism and lighting of Leonardo and the powerful draughtsmanship of Michelangelo became unified in the paintings of Raphael. In his short life he executed a number of large altarpieces, an impressive Classical fresco of the sea nymph, Galatea, outstanding portraits with two popes and a famous writer among them, and, while Michelangelo was painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling, a series of wall frescoes in the Vatican chambers nearby, of which the School of Athens is uniquely significant.

This fresco depicts a meeting of all the most learned ancient Athenians, gathered in a grand classical setting around the central figure of Plato, whom Raphael has famously modelled upon Leonardo da Vinci. The brooding figure of Heraclitus who sits by a large block of stone, is a portrait of Michelangelo, and is a reference to the latter's painting of the Prophet Jeremiah in the Sistine Chapel. His own portrait is to the right, beside his teacher, Perugino.[28]

But the main source of Raphael's popularity was not his major works, but his small Florentine pictures of the Madonna and Christ Child. Over and over he painted the same plump calm-faced blonde woman and her succession of chubby babies, the most famous probably being La Belle Jardinière ("The Madonna of the Beautiful Garden"), now in the Louvre. His larger work, the Sistine Madonna, used as a design for countless stained glass windows, has come, in the 21st century, to provide the iconic image of two small cherubs which has been reproduced on everything from paper table napkins to umbrellas.[29][30]

High Renaissance painting in Venice

Giovanni Bellini

Giovanni Bellini was the exact contemporary of his brother Gentile, his brother-in-law Mantegna and Antonello da Messina. Working most of his life in the studio of his brother, and strongly influenced by the crisp style of Mantegna, he does not appear to have produced an independently signed painting until he was in his late 50s. During the last 30 years of his life he was both extraordinarily productive and influential, having the guidance of both Giorgione and Titian. Bellini, like his much younger contemporary, Raphael, produced numerous small Madonnas in rich glowing colour, usually of more intense tonality than his Florentine counterpart. These Madonnas multiplied prolifically as they were reproduced by other members of the large Bellini studio, one tiny picture, The Circumcision of Christ existing in four or five almost identical versions.

Traditionally, in the painting of altarpieces of the Madonna and Child, the enthroned figure of the Virgin is accompanied by saints, who stand in defined spaces, separated physically in the form of a polytych or defined by painted architectural boundaries. Piero della Francesca used the Classical niche as a setting for his enthroned Madonnas, as Masaccio had used it as the setting for his Holy Trinity at Santa Maria Novella. Piero grouped saints around the throne, in the architectural space.

Bellini used this same form, known as Sacred conversations, in several of his later altarpieces such as that for the Venetian church of San Zaccaria. It is a masterful composition which extends the real architecture of the building into the illusionistic architecture of the painting, making the niche a sort of loggia opened up to the landscape and to daylight which streams across the figures of the Virgin and Child, the two female saints and the little angel who plays a viola making them brighter than the two elderly male saints who stand to the fore in the picture, Peter deep in thought and Jerome immersed in a book.[31]

Giorgione and Titian

Whilst the style of Giorgione's painting clearly relates to that of his presumed master, Giovanni Bellini, his subject matter makes him one of the most original and abstruse artists of the Renaissance. One of his paintings, of a landscape known as The Tempest, with a semi-naked woman feeding a baby, a clothed man, some classical columns and a flash of lightning, perhaps represents Adam and Eve in their post-Eden days, or perhaps it does not. Another painting attributed to him and traditionally known as The Three Philosophers, may represent the Magi planning their journey in search of the infant Christ, but this is not certain either.

One thing that appears to be certain is that Giorgione painted a female nude, the very first female nude that stands, or rather, lies, as a subject to be portrayed and admired for beauty alone. There are no need for Classical references in this painting, although in later nudes Titian, Velázquez, Veronese, Rembrandt, Rubens and even Manet saw fit to add some. They are the artistic heirs of Giorgione's nude.

On Giorgione's premature death, Titian completed the painting and went on to paint a great many more naked women, most frequently, as Botticelli did, disguising them as goddesses and surrounding them with sylvan woods and starry skies to make perfect decoration for the walls of rich clientele. But it was as a painter of portraits that Titian excelled, his longevity allowing him to achieve far more, both in the way of production and in stylistic development than either Giorgione or his Florentine contemporary Raphael were able to. Titian gave the world images of Pietro Aretino and Pope Paul III and many other people of his day, perhaps his most powerful portrait being that of Doge Andrea Gritti, ruler of Venice, who looms large in the picture space, one huge hand clasping his heavily buttoned robe in a dynamic Expressionistic gesture. Titian is also renowned for his religious painting, his last work being a turbulent and abstracted Pietà.[12][32]

Influence of Italian Renaissance painting

The lives of both Michelangelo and Titian extended well into the second half of the 16th century. Both saw their styles and those of Leonardo, Mantegna, Giovanni Bellini, Antonello da Messina and Raphael adapted by later painters to form a disparate style known as Mannerism, and move steadily towards the great outpouring of imagination and painterly virtuosity of the Baroque period.

The artist who most extended the trends in Titian's large figurative compositions is Tintoretto, although his personal manner was such that he only lasted nine days as Titian's apprentice. Rembrandt's knowledge of the works of both Titian and Raphael is apparent in his portraits. The direct influences of Leonardo and Raphael upon their own pupils was to effect generations of artists including Poussin and schools of Classical painters of the 18th and 19th centuries. Antonello da Messina's work had a direct influence on Albrecht Dürer and Martin Schongauer and through the latter's engravings, countless artists including the German, Dutch and English schools of stained glass makers extending into the early 20th century.[16]

Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling and later The Last Judgment had direct influence on the figurative compositions firstly of Raphael and his pupils and then almost every subsequent 16th-century painter who looked for new and interesting ways to depict the human form. It is possible to trace his style of figurative composition through Andrea del Sarto, Pontormo, Bronzino, Parmigianino, Veronese, to el Greco, Carracci, Caravaggio, Rubens, Poussin and Tiepolo to both the Classical and the Romantic painters of the 19th century such as Jacques-Louis David and Delacroix.

Under the influence of the Italian Renaissance painting, many modern academies of art, such as the Royal Academy, were founded, and it was specifically to collect the works of the Italian Renaissance that some of the world's best known art collections, such as the National Gallery, London, were formed.

_-_WGA24437.jpg)

See also

- Themes in Italian Renaissance painting

- Renaissance architecture

- Mannerism

- Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

- Timeline of Italian painters to 1800

Notes and references

- ↑ e.g. Antonello da Messina who travelled from Sicily to Venice via Naples.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Frederick Hartt, A History of Italian Renaissance Art, (1970)

- 1 2 Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, (1974)

- ↑ Margaret Aston, The Fifteenth Century, the Prospect of Europe, (1979)

- ↑ Keith Christiansen, Italian Painting, (1992)

- ↑ John White, Duccio, (1979)

- 1 2 Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, (1568)

- ↑ All three are reproduced and compared at Italian Renaissance painting, development of themes

- 1 2 Sarel Eimerl, The World of Giotto, (1967)

- ↑ Mgr. Giovanni Foffani, Frescoes by Giusto de' Menabuoi, (1988)

- ↑ Helen Gardner, Art through the Ages, (1970)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 R.E. Wolf and R. Millen, Renaissance and Mannerist Art, (1968)

- 1 2 Ornella Casazza, Masaccio and the Brancacci Chapel, (1990)

- ↑ Annarita Paolieri, Paolo Uccello, Domenico Veneziano, Andrea del Castagno, (1991)

- ↑ Peter Murray and Pier Luigi Vecchi, Piero della Francesca, (1967)

- 1 2 3 4 Diana Davies, Harrap's Illustrated Dictionary of Art and Artists, (1990)

- 1 2 Elena Lanzanova, trans. Giorgina Arcuri, Restoration Of Mantegna’S San Zeno Altarpiece In Florence, Arcadja, (2008-06-23), (accessed: 2012-07-13)

- ↑ metmuseum Madonna and Child with Saints Girolamo dai Libri (Italian, Verona 1474–1555 Verona), edit: 2000–2012

- ↑ Schifanoia means "disgust of annoyances", or "Sans Souci", and indeed it lacks anything so commonplace as a kitchen so that all the food had to be transported.

- ↑ Ranieri Varese, Il Palazzo di Schifanoia, (1980)

- ↑ Ilan Rachum, The Renaissance, an Illustrated Encyclopedia, (1979)

- 1 2 Hugh Ross Williamson, Lorenzo the Magnificent, (1974)

- ↑ Umberto Baldini, Primavera, (1984)

- 1 2 3 Giacometti, Massimo (1986). The Sistine Chapel.

- 1 2 T.L.Taylor, The Vision of Michelangelo, Sydney University, (1982)

- ↑ Gabriel Bartz and Eberhard König, Michelangelo, (1998)

- ↑ Ludwig Goldschieder, Michelangelo, (1962)

- ↑ Some sources identify this figure as Il Sodoma, but it is an older, grey-haired man, while Sodoma was in his 30s. Moreover, it strongly resembles several self-portraits of Perugino, who would have been about 60 at the time.

- ↑ David Thompson, Raphael, the Life and Legacy, (1983)

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Cuzin, Raphael, his Life and Works, (1985)

- ↑ Olivari, Mariolina (1990). Giovanni Bellini.

- ↑ Cecil Gould, Titian, (1969)

Bibliography

General

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, (1568), 1965 edition, trans George Bull, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-044164-6

- Frederick Hartt, A History of Italian Renaissance Art, (1970) Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-23136-2

- R.E. Wolf and R. Millen, Renaissance and Mannerist Art, (1968) Abrams, ISBN unknown

- Keith Christiansen, Italian Painting, (1992) Hugh Lauter Levin/Macmillan, ISBN

0883639718

- Helen Gardner, Art through the Ages, (1970) Harcourt, Brace and World, ISBN 0-15-503752-8

- Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy, (1974) Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-881329-5

- Margaret Aston, The Fifteenth Century, the Prospect of Europe, (1979) Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-33009-3

- Ilan Rachum, The Renaissance, an Illustrated Encyclopedia, (1979) Octopus, ISBN 0-7064-0857-8

- Diana Davies, Harrap's Illustrated Dictionary of Art and Artists, (1990) Harrap Books, ISBN 0-245-54692-8

- Luciano Berti, Florence: the city and its art, (1971) Scala, ISBN unknown

- Rona Goffen, Renaissance Rivals: Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Titian, (2004) Yale University Press, ISBN 0300105894

- Arnold Hauser, The Social History of Art, Vol. 2: Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque, (1999) Routledge, ISBN 0415199468

- Luciano Berti, The Ufizzi, (1971) Scala, Florence. ISBN unknown

- Michael Wilson, The National Gallery, London, (1977) Scala, ISBN 0-85097-257-4

- Hugh Ross Williamson, Lorenzo the Magnificent, (1974) Michael Joseph, ISBN 0-7181-1204-0

- Sciacca, Christine (2012). Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance: Painting and Illumination, 1300-1500. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-1-60606-126-8.

Painters

- John White, Duccio, (1979) Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-09135-8

- Cecilia Jannella, Duccio di Buoninsegna, (1991) Scala/Riverside, ISBN 1-878351-18-4

- Sarel Eimerl, The World of Giotto, (1967) Time/Life, ISBN 0-900658-15-0

- Mgr. Giovanni Foffani, Frescoes by Giusto de' Menabuoi, (1988) G. Deganello, ISBN unknown

- Ornella Casazza, Masaccio and the Brancacci Chapel, (1990) Scala/Riverside, ISBN 1-878351-11-7

- Annarita Paolieri, Paolo Uccello, Domenico Veneziano, Andrea del Castagno, (1991) Scala/Riverside, ISBN 1-878351-20-6

- Alessandro Angelini, Piero della Francesca, (1985) Scala/Riverside, ISBN 1-878351-04-4

- Peter Murray and Pier Luigi Vecchi, Piero della Francesca, (1967) Penguin, ISBN 0-14-008647-1

- Umberto Baldini, Primavera, (1984) Abrams, ISBN 0-8109-2314-9

- Ranieri Varese, Il Palazzo di Schifanoia, (1980) Specimen/Scala, ISBN unknown

- Angela Ottino della Chiesa, Leonardo da Vinci, (1967) Penguin, ISBN 0-14-008649-8

- Jack Wasserman, Leonardo da Vinci, (1975) Abrams, ISBN 0-8109-0262-1

- Massimo Giacometti, The Sistine Chapel, (1986) Harmony Books, ISBN 0-517-56274-X

- Ludwig Goldschieder, Michelangelo, (1962) Phaidon, ISBN unknown

- Gabriel Bartz and Eberhard König, Michelangelo, (1998) Könemann, ISBN 3-8290-0253-X

- David Thompson, Raphael, the Life and Legacy, (1983) BBC, ISBN 0-563-20149-5

- Jean-Pierre Cuzin, Raphael, his Life and Works, (1985) Chartwell, ISBN 0-89009-841-7

- Mariolina Olivari, Giovanni Bellini, (1990) Scala. ISBN unknown

- Cecil Gould, Titian, (1969) Hamlyn, ISBN unknown

.jpg)