Islay

| Gaelic name |

|

|---|---|

| Norse name | Íl[1] |

| Meaning of name | Unknown |

| Location | |

Islay Islay shown within Argyll and Bute | |

| OS grid reference | NR370598 |

| Coordinates | 55°46′N 6°09′W / 55.77°N 6.15°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Islay |

| Area | 61,956 hectares (239 sq mi)[2] |

| Area rank | 5 [3] |

| Highest elevation | Beinn Bheigeir 491 metres (1,611 ft)[4] |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Argyll and Bute |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 3,228[5] |

| Population rank | 7[5] [3] |

| Population density | 5.2 people/km2[2][5] |

| Largest settlement | Port Ellen[6] |

Islay (/ˈaɪlə/ EYE-lə; Scottish Gaelic: Ìle, pronounced [ˈiːlə]) is the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Known as "The Queen of the Hebrides",[7] it lies in Argyll just south west of Jura and around 40 kilometres (25 mi) north of the Irish coast. The island's capital is Bowmore where the distinctive round Kilarrow Parish Church and a distillery are located.[8] Port Ellen is the main port.[9]

Islay is the fifth-largest Scottish island and the seventh-largest island surrounding Great Britain, with a total area of almost 620 square kilometres (239 sq mi).[Note 1] There is ample evidence of the prehistoric settlement of Islay and the first written reference may have come in the 1st century AD. The island had become part of the Gaelic Kingdom of Dál Riata during the Early Middle Ages before being absorbed into the Norse Kingdom of the Isles. The later medieval period marked a "cultural high point" with the transfer of the Hebrides to the Kingdom of Scotland and the emergence of the Clan Donald Lordship of the Isles, originally centred at Finlaggan.[12] During the 17th century the Clan Donald star waned, but improvements to agriculture and transport led to a rising population, which peaked in the mid-19th century.[2] This was followed by substantial forced displacements and declining resident numbers.

Today, it has over 3,000 inhabitants and the main commercial activities are agriculture, malt whisky distillation and tourism. The island has a long history of religious observance and Scottish Gaelic is spoken by about a quarter of the population.[13] Its landscapes have been celebrated through various art forms and there is a growing interest in renewable energy. Islay is home to many bird species such as the wintering populations of Greenland white-fronted and barnacle goose, and is a popular destination throughout the year for birdwatchers. The climate is mild and ameliorated by the Gulf Stream.

Name

Islay was probably recorded by Ptolemy as Epidion,[14] the use of the "p" suggesting a Brittonic or Pictish tribal name.[15] In the seventh century Adomnán referred to the island as Ilea[16] and the name occurs in early Irish records as Ile and as Íl in Old Norse. The root is not Gaelic and of unknown origin.[1][Note 2] In seventeenth century maps the spelling appears as "Yla" or "Ila", a form still used in the name of the whisky Caol Ila.[18][19] In poetic language Islay is known as Banrìgh Innse Gall,[7] or Banrìgh nan Eilean[20] usually translated as "Queen of the Hebrides"[Note 3] and Eilean uaine Ìle – the "green isle of Islay"[17] A native of Islay is called an Ìleach, pronounced [ˈiːləx].[17]

The obliteration of pre-Norse names is almost total and place names on the island are a mixture of Norse and later Gaelic and English influences.[22][23] Port Askaig is from the Norse ask-vík, meaning "ash tree bay" and the common suffix -bus is from the Norse bólstaðr, meaning "farm".[24] Gaelic names, or their anglicised versions such as Ardnave Point, from Àird an Naoimh, "height of the saint" are very common.[25] Several of the villages were developed in the 18th and 19th centuries and English is a stronger influence in their names as a result. Port Charlotte for example, was named after Lady Charlotte Campbell, daughter of the island's then owner, Daniel Campbell of Shawfield.[26]

Geography

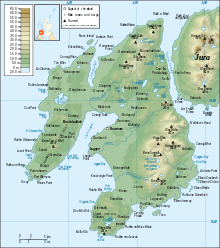

Islay is 40 kilometres (25 mi) long from north to south and 24 kilometres (15 mi) broad. The east coast is rugged and mountainous, rising steeply from the Sound of Islay, the highest peak being Beinn Bheigier, which is a Marilyn at 1,612 feet (491 m). The western peninsulas are separated from the main bulk of the island by the waters of Loch Indaal to the south and Loch Gruinart to the north.[27] The fertile and windswept southwestern arm is called The Rinns, and Ardnave Point is a conspicuous promontory on the northwest coast. The south coast is sheltered from the prevailing winds and, as a result, relatively wooded.[28][29][30] The fractal coast has numerous bays and sea lochs, including Loch an t-Sailein, Aros Bay and Claggain Bay.[28] In the far southwest is a rocky and now largely uninhabited peninsula called The Oa, the closest point in the Hebrides to Ireland.[31]

The island's population is mainly centred around the villages of Bowmore and Port Ellen. Other smaller villages include Bridgend, Ballygrant, Port Charlotte, Portnahaven and Port Askaig. The rest of the island is sparsely populated and mainly agricultural.[32] There are several small freshwater lochs in the interior including Loch Finlaggan, Loch Ballygrant, Loch Lossit and Loch Gorm, and numerous burns throughout the island, many of which bear the name "river" despite their small size. The most significant of these are the River Laggan which discharges into the sea at the north end of Laggan Bay, and the River Sorn which, draining Loch Finlaggan, enters the head of Loch Indaal at Bridgend.[28]

There are numerous small uninhabited islands around the coasts, the largest of which are Eilean Mhic Coinnich and Orsay off the Rinns, Nave Island on the northwest coast, Am Fraoch Eilean in the Sound of Islay, and Texa off the south coast.[28]

Geology and geomorphology

The underlying geology of Islay is intricate for such a small area.[2] The deformed Palaeoproterozoic igneous rock of the Rhinns complex is dominated by a coarse-grained gneiss cut by large intrusions of deformed gabbro. Once thought to be part of the Lewisian complex, it lies beneath the Colonsay Group of metasedimentary rocks[33][34] that forms the bedrock at the northern end of the Rinns. It is a quartz-rich metamorphic marine sandstone that may be unique to Scotland and which is nearly 5,000 metres thick.[35] South of Rubh' a' Mhail there are outcrops of quartzite, and a strip of mica schist and limestone cuts across the centre of the island from The Oa to Port Askaig. Further south is a band of metamorphic quartzite and granites, a continuation of the beds that underlie Jura. The geomorphology of these last two zones is dominated by a fold known as the Islay Anticline. To the south is a "shattered coastline" formed from mica schist and hornblende.[2][36][37] The older Bowmore Group sandstones in the west centre of the island are rich in feldspar and may be of Dalradian origin.[38][Note 4]

.

Loch Indaal was formed along a branch of the Great Glen Fault called the Loch Gruinart Fault; its main line passes just to the north of Colonsay. This separates the limestone, igneous intrusions and Bowmore sandstones from the Colonsay Group rocks of the Rhinns.[39] The result is occasional minor earth tremors.[40]

There is a tillite bed near Port Askaig that provides evidence of an ice age in the Precambrian.[37][41] In comparatively recent times the island was ice-covered during the Pleistocene glaciations save for Beinn Tart a' Mhill on the Rinns, which was a nunatak on the edge of the ice sheet.[42] The complex changes of sea level due to melting ice caps and isostasy since then have left a series of raised beaches around the coast.[32] Throughout much of late prehistory the low-lying land between the Rinns and the rest of the island was flooded, creating two islands.[43]

Climate

The influence of the Gulf Stream keeps the climate mild compared to mainland Scotland. Snow is rarely seen at sea level and frosts are light and short-lived.[44] However, wind speeds average 19 to 28 kilometres per hour (10 to 15 kn) annually[45] and winter gales sweep in off the Atlantic, gusting up to 185 kilometres per hour (115 mph).[46] This can make travelling and living on the island during the winter difficult,[47] while ferry and air links to the mainland can suffer delays. The driest months are April to July and the warmest are May to September, which as a result are the busiest times for tourism.[48][49] Sunshine hours are typically highest around the coasts, especially to the west.[44]

| Climate data for Islay | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

7.4 (45.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.8 (55) |

14.5 (58.1) |

16.1 (61) |

16.3 (61.3) |

14.7 (58.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.6 (52.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.1 (37.6) |

3.0 (37.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

4.7 (40.5) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

11.1 (52) |

11.2 (52.2) |

9.7 (49.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

5.2 (41.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 142.5 (5.61) |

98.2 (3.866) |

104.5 (4.114) |

67.1 (2.642) |

54.1 (2.13) |

61.5 (2.421) |

77.5 (3.051) |

98.7 (3.886) |

118.6 (4.669) |

142.7 (5.618) |

136.6 (5.378) |

134.5 (5.295) |

1,236.4 (48.677) |

| Source: Islay Info[48] | |||||||||||||

Prehistory

The earliest settlers on Islay were nomadic hunter-gatherers who may have first arrived during the Mesolithic period after the retreat of the Pleistocene ice caps. A flint arrowhead, which was found in a field near Bridgend in 1993 and dates from 10,800 BC, is amongst the earliest evidence of a human presence found so far in Scotland.[50][Note 5] Stone implements of the Ahrensburgian culture found at Rubha Port an t-Seilich near Port Askaig by foraging pigs in 2015 probably came from a summer camp used by hunters travelling round the coast in boats.[53][54] Mesolithic finds have been dated to 7000 BC using radiocarbon dating of shells and debris from kitchen middens.[55][56] By the Neolithic, settlements had become more permanent,[57] allowing for the construction of several communal monuments.[58]

The most spectacular prehistoric structure on the island is Dun Nosebridge. This 375 square metres (4,040 sq ft) Iron Age fort occupies a prominent crag and has commanding views of the surrounding landscape. The name's origin is probably a mixture of Gaelic and Old Norse: Dun in the former language means "fort" and knaus-borg in the latter means "fort on the crag".[59] There is no evidence that Islay was ever subject to Roman military control although small numbers of finds such as a coin and a brooch from the third century AD suggest links of some kind with the intermittent Roman presence on the mainland.[60] The ruins of a broch at Dùn Bhoraraic south east of Ballygrant and the remains of numerous Atlantic roundhouses indicate the influences of northern Scotland, where these forms of building originate.[61][62] There are also various crannogs on Islay, including sites in Loch Ardnave, Loch Ballygrant and Loch Allallaidh in the south east where a stone causeway leading out to two adjacent islands is visible beneath the surface of the water.[28][61]

History

Dál Riata

By the 6th century AD Islay, along with much of the nearby mainland and adjacent islands, and Moyle (in Ulster), lay within the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata with strong links to Ireland. The widely accepted view is that Dál Riata was established by Gaelic migrants from Ulster, displacing a former Brythionic culture (such as the Picts). Nevertheless, some controversially claim that the Gaels in this part of Scotland were indigenous to the area.[63] Dál Riata was divided into a small number of regions, each controlled by a particular kin group; according to the Senchus fer n-Alban ("The History of the Men of Scotland"), it was the Cenél nÓengusa for Islay and Jura.

In 627 the son of a king of the Irish Uí Chóelbad, a branch of the Dál nAraidi kingdom of Ulster (not to be confused with Dál Riata), was killed on Islay at the unidentified location of Ard-Corann by a warrior in an army led by King Connad Cerr of the Corcu Réti (the collective term for the Cenél nGabráin and Cenél Comgaill, before they split), based at Dunadd.[64] The Senchus also lists what is believed to be the oldest reference to a naval battle in the British Isles—a brief record of an engagement between rival Dál Riatan groups in 719.[65]

There is evidence of another kin group on Islay - the Cenél Conchride, supposedly descended from a brother of the legendary founder of Dál Riata, king Fergus Mór, but the existence of the Cenél Conchride seems to have been brief and the 430 households of the island are later said to have been comprised from the families of just three great-grandsons of the eponymous founder of Cenél nÓengus: Lugaid, Connal and Galán.[64]

Norse influence and the Kingdom of the Isles

The 9th century arrival of Scandinavian settlers on the western seaboard of the mainland had a long-lasting effect, beginning with the destruction of Dál Riata. As is the case in the Northern Isles, the derivation of place names suggests a complete break from the past. Jennings and Kruse conclude that although there were settlements prior to the Norse arrival "there is no evidence from the onomasticon that the inhabitants of these settlements ever existed".[67] Gaelic continued to exist as a spoken language in the southern Hebrides throughout the Norse period, but the place name evidence suggests it had a lowly status, possibly indicating an enslaved population.[68] The former lands of Dal Riata aquired the geographic description Argyle (now Argyll): the gaelic coast.

Consolidating their gains, the norse settlers established the Kingdom of the Isles, which became part of the crown of Norway following Norweigan unification. To Norway, the islands became known as Suðreyjar (Old Norse, traditionally anglicised as Sodor, or Sudreys), meaning southern isles. For the next four centuries and more this Kingdom was under the control of rulers of mostly Norse origin.

Godred Crovan was one of the most significant of the rulers of this sea kingdom. Though his origins are obscure, it is known that Godred was a Norse-Gael, with a connection to Islay. The Chronicles of Mann call Godred the son of Harald the Black of Ysland, (his place or origin variously interpreted as Islay, Ireland or Iceland) and state he "so tamed the Scots that no one who built a ship or boat dared use more than three iron bolts".[69][70]

Godred also became King of Dublin at an unknown date, although in 1094 he was driven out of the city by Muircheartach Ua Briain, later known as High King of Ireland, according to the Annals of the Four Masters. He died on Islay "of pestilence", during the following year.[69][71][72] A local tradition suggests that a standing stone at Carragh Bhan near Kintra marks Godred Crovan's grave.[66][73] A genuine 11th century Norse grave-slab was found at Dóid Mhàiri in 1838, although it was not associated with a burial. The slab is decorated with foliage in the style of Ringerike Viking art and an Irish-style cross, the former being unique in Scandinavian Scotland.[66]

Following Godred's death, the local population resisted Norway's choice of replacement, causing Magnus, the Norweigan king, to launch a military campaign to assert his authority. In 1098, under pressure from Magnus, the king of Scotland quitclaimed to Magnus all sovereign authority over the isles.

Somerled

In the mid 12th century, a granddaughter of Godred Crovan's married the ambitious Somerled, a Norse-Gael Argyle nobleman. Godred Olafsson, grandson of Crovan, was an increasingly unpopular King of the Isles at the time, spurring Somerled into action. The two fought the Battle of Epiphany in the seas off Islay in January 1156.[Note 6] The result was a bloody stalemate, and the island kingdom was temporarily divided, with Somerled taking control of the southern Hebrides. Two years later Somerled completely ousted Godred and re-united the kingdom.

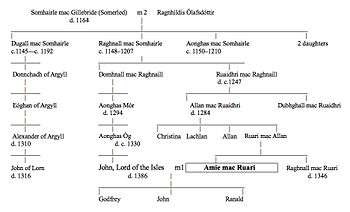

Somerled built the sea fortress of Claig Castle on an island between Islay and Jura, to establish control of the Sound of Islay. On account of the Corryvreckan whirlpool to the north of Jura, the Sound was the main safe sea route between the mainland and the rest of the Hebrides; Claig Castle essentially gave Somerled control of sea traffic. Following Somerled's 1164 death, the realm was divided between Godred's heirs, and Somerled's sons,[74][75][76] whose descendants continued to describe themselves as King of the Sudreys until the 13th century. Somerled's grandson, Donald received Islay, along with Claig Castle, and the adjacent part of Jura as far north as Loch Tarbert.

Nominal Norweigan authority had been re-established after Somerled's death, but by the mid 13th century, increased tension between Norway and Scotland lead to a series of battles, culminating in the Battle of Largs, shortly after which the Norweigan king died. In 1266, his more peaceable successor ceded his nominal authority over Suðreyjar to the Scottish king (Alexander III) by the Treaty of Perth, in return for a very large sum of money.[77][78] Alexander generally acknowledged the semi-independent authority of Somerled's heirs; the former Suðreyjar had become a Scottish crown dependency, rather than part of Scotland.

Scottish rule

Lords of the Isles

By this point, Somerled's descendants had formed into three families - the heirs of Donald (the MacDonalds, lead by Aonghas Óg MacDonald), those of Donald's brother (the Macruari, lead by Ruaidhri mac Ailein), and those of Donald's uncle (the MacDougalls, lead by Alexander MacDougall). At the end of the 13th century, when king John Balliol was challenged for the throne by Robert the Bruce, the MacDougalls backed Balliol, while the Macruari and MacDonalds backed Robert. When Robert won, he declared the MacDougall lands forfeit, and distributed them between the MacDonalds and Macruari (the latter already owning much of Lorne, Uist, parts of Lochaber, and Garmoran).[79]

The Macruari territories were eventually inherited by Amy of Garmoran.,[80][81][82] who married her MacDonald cousin John of Islay in the 1330s;[83] having succeeded Aonghus Óg as head of the MacDonalds, he now controlled significant stretches of the western seaboard of Scotland from Morvern to Loch Hourn, and the whole of the Hebrides save for Skye (which Robert had given to Hugh of Ross instead).[82] From 1336 onwards John began to style himself Dominus Insularum—"Lord of the Isles", a title that implied a connection to the earlier Kings of the Isles and by extension a degree of independence from the Scottish crown;[82][83][84] this honorific was claimed by his heirs for several generations.[85] The MacDonalds had thus achieved command of a strong semi-independent maritime kingdom, and considered themselves equals of the kings of Scotland, Norway, and England.[86]

Initially, their power base was on the shores of Loch Finlaggan in northeastern Islay, near the present-day village of Caol Ila. Successive chiefs of Clan Donald were proclaimed Lord of the Isles there, upon an ancient seven-foot-square coronation stone bearing footprint impressions in which the new ruler stood barefoot and was anointed by the Bishop of Argyll and seven priests.[87] The Lord's advisory "Council of the Isles" met on Eilean na Comhairle[Note 7] (Council Island), in Loch Finlaggan on Islay, within a timber framed crannog that had originally been constructed in the 1st century BC.

The Islay Charter, a record of lands granted to an Islay resident in 1408, Brian Vicar MacKay, by Domhnall of Islay, Lord of the Isles, is one of the earliest records of Gaelic in public use, and is a significant historical document.[90] In 1437, the Lordship was substantially expanded when Alexander, the Lord of the Isles, inherited the rule of Ross maternally; this included Skye. The expansion of MacDonald control caused the "heart of the Lordship" to move to the twin castles of Aros and Ardtornish, in the Sound of Mull.[91]

In 1462, the last and most ambitious of the Lords, John MacDonald II, struck an alliance with Edward IV of England under terms of the Treaty of Ardtornish-Westminster with the goal of conquering Scotland. The onset of the Wars of the Roses prevented the treaty from being discovered by Scottish agents, and Edward from fulfilling his obligations as an ally. A decade later, in 1475, it had come to the attention of the Scottish court, but calls for forfeiture of the Lordship were calmed when John quitclaimed his mainland territories, and Skye. However, ambition wasn't given up so easily, and John's nephew launched a severe raid on Ross, but it ultimately failed. Within 2 years of the raid, in 1493, MacDonald was compelled to forfeit his estates and titles to James IV of Scotland; by this forfeiture, the lands became part of Scotland, rather than a crown dependency.

James ordered Finlaggan demolished, its buildings razed, and the coronation stone destroyed, to discourage any attempts at restoration of the Lordship.[92][93][Note 8] When Martin Martin visited Islay in the late 17th century he recorded a description of the coronations Finlaggan had once seen.[Note 9]. John was exiled from his former lands, and his former subjects now considered themselves to have no superior except the king. A charter was soon sent from the Scottish King confirming this state of affairs; it declares that Skye and the Outer Hebrides are to be considered independent from the rest of the former Lordship, leaving only Islay and Jura remaining in the comital unit.

16th and 17th centuries

Initially dispossessed in the wake of royal opposition to the Lordship, Clan MacDonald of Dunnyveg's holdings in Islay were restored in 1545.[96] The MacLean family had been granted land in Jura in 1390, by the MacDonalds, and in 1493 had thus been seen as the natural replacement for them, leading to a branch of the MacLeans being granted Dunyvaig Castle by king James, and expanding into Islay. Naturally, the restoration of the MacDonalds created some hostility with the MacLeans; in 1549, after observing that Islay was fertile, fruitful, and full of natural pastures, with good hunting and plentiful salmon and seals, Dean Monro describes Dunyvaig, and Loch Gorm Castle "now usurped be M’Gillayne of Doward".[97][Note 10]. The dispute continued for decades, and in 1578 the Macleans were expelled from Loch Gorm by force, and in 1598 their branch was finally defeated at the Battle of Traigh Ghruinneart.

However, when Sorley Boy MacDonnell (of the Islay MacDonalds) had a clash with the Irish branch of the Macleans, and the unpopularity of the MacDonalds in Edinburgh (where their use of Gaelic was regarded as barbaric), weakened their grip on their southern Hebridean possessions. In 1608, Coupled with MacDonald hostility to the Scottish reformation, this lead the Scottish-English crown to mount an expedition to subdue them. In 1614 the crown handed Islay to Sir John Campbell of Cawdor, in return for an undertaking to pacify it;[98][99] this the Campbells eventually achieved. Under Campbell influence, shrieval authority was established under the sheriff of Argyll. With inherited Campbell control of the sheriffdom, comital authority was relatively superfluous, and the provincial identity (medieval latin:provincia) of Islay-Jura faded away.

The situation was soon complicated by the Civil War, when Archibald, the head of the most powerful branch of the Campbells, was the de-facto head of Covenanter government, while other branches (and even Archibald's son) were committed Royalists. A Covenanter army under Sir David Leslie arrived on Islay in 1647, and besieged the royalist garrison at Dunnyvaig, laying waste to the island.[100] It was not until 1677 that the Campbells felt sufficiently at ease to construct Islay House at Bridgend to be their principal, and unfortified, island residence.[101][Note 11]

British era

18th and 19th centuries

At the beginning of the 18th century much of the population of Argyll was to be found dispersed in small clachans of farming families[104] and only two villages of any size—Killarow near Bridgend and Lagavulin—existed on Islay at the time.[105] (Killarow had a church and tolbooth and houses for merchants and craft workers but was razed in the 1760s to "improve" the grounds of Islay House.)[105] The agricultural economy was dependent on arable farming including staples such as barley and oats supplemented with stock-rearing. The carrying capacity of the island was recorded at over 6,600 cows and 2,200 horses in a 1722 rental listing.[106]

In 1726 Islay was purchased by Daniel Campbell of Shawfield.[107][108] Following Jacobite insurrections, the Heritable Jurisdictions Act abolished comital authority, and Campbell control of the sheriffdom; they could now only assert influence as Landlords.

A defining aspect of 19th century Argyll was the gradual improvement of transport infrastructure.[109] Roads were built, the Crinan canal shortened the sea distance to Glasgow and the numerous traditional ferry crossings were augmented by new quays. Rubble piers were built at several locations on Islay and a new harbour was constructed at Port Askaig.[110] Initially, a sense of optimism in the fishing and cattle trades prevailed and the population expanded, partly as a result of the 18th century kelp boom and the introduction of the potato as a staple.[111] The population of the island had been estimated at 5,344 in 1755 and grew to over 15,000 by 1841.

Islay remained with the Campbells of Shawfield until 1853 when it was sold to James Morrison of Berkshire, ancestor of the third Baron Margadale, who still owns a substantial portion of the island.[108] The sundering of the relationship between the landowners and the island's residents proved consequential. When the estate owners realised they could make more money from sheep farming than from the indigenous small farmers, wholesale Clearances became commonplace. Four hundred people emigrated from Islay in 1863 alone, some for purely economic reasons, but many others having been forced off the land their predecessors had farmed for centuries. In 1891 the census recorded only 7,375 citizens, with many evictees making new homes in Canada, the United States and elsewhere. The population continued to decline for much of the 20th century and today is about 3,500.[2][112][113]

In 1899, counties were formally created, on shrieval boundaries, by a Scottish Local Government Act; Islay therefore became part of the County of Argyll.

World wars

During World War I two troop ships foundered off Islay within a few months of each other in 1918. The American vessel SS Tuscania was torpedoed by UB-77 on 5 February with the loss of over 160 lives and now lies in deep water 6.4 kilometres (4 mi) west of the Mull of Oa.[114] On 6 October HMS Otranto was involved in a collision with HMS Kashmir in heavy seas while convoying troops from New York. Otranto lost steering and drifted towards the west coast of the Rinns. Answering her SOS the destroyer HMS Mounsey attempted to come alongside and managed to rescue over 350 men. Nonetheless, the Otranto was wrecked on the shore near Machir Bay with a total loss of 431 lives.[115] A monument was erected on the coast of The Oa by the American Red Cross to commemorate the sinking of these two ships.[116] A military cemetery was created at Kilchoman where the dead from both nations in the latter disaster were buried (the American bodies later removed).[117]

During World War II, the RAF built an airfield at Glenegedale which later became the civil airport for Islay. There was also an RAF Coastal Command flying boat base at Bowmore from 13 March 1941 using Loch Indaal.[118] In 1944 an RCAF 422 Squadron Sunderland flying boat's crew were rescued after their aircraft landed off Bowmore but broke from her moorings in a gale and sank.[119] There was an RAF Chain Home radar station at Saligo Bay and RAF Chain Home Low station at Kilchiaran.[120][121]

Following late 20th century reforms, Islay is now within the wider region of Argyll and Bute.

Economy

The mainstays of the modern Islay economy are agriculture and fishing, distilling and tourism.[122]

Agriculture and fishing

Much of Islay remains owned by a few non-resident estate owners and sheep farming and the few dairy cattle herds are run by tenant farmers.[122] Islay has some fine wild brown trout and salmon fishing[123] and in September 2003 the European Fishing Competition was held on five of the island's numerous lochs; this was "the biggest fishing event ever to be held in Scotland".[124] Sea angling is also popular, especially off the west coast and over the many shipwrecks around the coast.[124] There are about 20 commercial boats with crab, lobster and scallop fishing undertaken from Port Askaig, Port Ellen and Portnahaven.[125][126]

Distilling

Islay is one of five whisky distilling localities and regions in Scotland whose identity is protected by law.[127] There are eight active distilleries and the industry is the island's second largest employer after agriculture.[128][129] Those on the south of the island produce malts with a very strong peaty flavour, considered to be the most intensely flavoured of all whiskies. From east to west they are Ardbeg, Lagavulin, and Laphroaig. On the north of the island Bowmore, Bruichladdich, Caol Ila and Bunnahabhain are produced, which are substantially lighter in taste.[130][131] Kilchoman is a microdistillery opened in 2005 toward the west coast of the Rinns.[132]

The oldest record of a legal distillery on the island refers to Bowmore in 1779 and at one time there were up to 23 distilleries in operation.[133] For example, Port Charlotte distillery operated from 1829 to 1929[134] and Port Ellen is also closed although it remains in business as a malting.[133] In March 2007 Bruichladdich announced that they would reopen Port Charlotte distillery using equipment from the Inverleven distillery.[134]

Tourism

Some 45,000 summer visitors arrive each year by ferry and a further 11,000 by air.[135] The main attractions are the scenery, history, bird watching and the world-famous whiskies.[136] The distilleries operate various shops, tours, and visitor centres,[137] and the Finlaggan Trust has a visitor centre which is open daily during the summer.[138]

Renewable energy

The location of Islay, exposed to the full force of the North Atlantic, has led to it being the site of a pioneering, and Scotland's first, wave power station near Portnahaven. The Islay LIMPET (Land Installed Marine Powered Energy Transformer) wave power generator was designed and built by Wavegen and researchers from the Queen's University of Belfast, and was financially backed by the European Union. Known as Limpet 500, due to cabling constraints its capacity is limited to providing up to 150 kW of electricity into the island's grid.[139] In 2000 it became the world's first commercial wave power station. In March 2011 the largest tidal array in the world was approved by the Scottish Government with 10 planned turbines predicted to generate enough power for over 5,000 homes. The project will be located in the Sound of Islay which offers both strong currents and shelter from storms.[140]

Transport

Many of the roads on the island are single-track with passing places. The two main roads are the A846 from Ardbeg to Port Askaig via Port Ellen and Bowmore, and the A847 which runs down the east coast of the Rhinns.[28] The island has its own bus service provided by Islay Coaches and Glenegedale Airport offers flights to and from Glasgow International Airport and on a less regular basis to Oban and Colonsay.[141]

Caledonian MacBrayne operate regular ferry services to Port Ellen and Port Askaig from Kennacraig, taking about two hours. Ferries to Port Askaig also run on to Scalasaig on Colonsay and, on summer Wednesdays, to Oban. The purpose-built vessel, MV Finlaggan entered service in 2011.[142] ASP Ship Management Ltd operate a small car ferry on behalf of Argyll & Bute Council from Port Askaig to Feolin on Jura.[143] Kintyre Express will begin operating passenger only services between Port Ellen and Ballycastle in Northern Ireland from Fridays to Mondays through June, July and August.

There are various lighthouses on and around Islay as an aid to navigation. These include the Rinns of Islay light built on Orsay in 1825 by Robert Stevenson,[144] Ruvaal at the north eastern tip of Islay constructed in 1859,[145] Carraig Fhada at Port Ellen, which has an unusual design,[146] and Dubh Artach, an isolated rock tower some 35 kilometres (22 mi) to the north west of Ruvaal.

Other activities

Since 1973 the Ileach has been delivering news to the people of Islay every fortnight and was named community newspaper of the year in 2007.[147][148] The Islay Ales Brewery brews various real ales at its premises near Bridgend.[149] In the early 21st century a campus of Sabhal Mòr Ostaig was set up on Islay, Ionad Chaluim Chille Ìle, which teaches Gaelic language, culture and heritage.[150] The Port Mòr community centre at Port Charlotte, which is equipped with a micro-wind turbine and a ground-source heating system, is the creation of local development trust Iomairt Chille Chomain.[151][152]

Gaelic language

Islay has historically been a very strong Gaelic-speaking area. In both the 1901 and 1921 censuses, all parishes in Islay were reported to be over 75 percent Gaelic-speaking. By 1971, the Rhinns had dropped to 50-74 percent Gaelic speakers and the rest of Islay to 25-49 percent Gaelic speaker overall.[13] By 1991 about a third of the island's population were Gaelic speakers.[153] In the 2001 census this had dropped to 24 percent, which, while a low figure overall, nonetheless made it the most strongly Gaelic-speaking island in Argyll and Bute after Tiree, with the highest percentage recorded in Portnahaven (32 percent) and the lowest in Gortontaoid (17 percent), with the far north and south of the island being the weakest areas in general.[13]

The Islay dialect is distinctive. It patterns strongly with other Argyll dialects, especially those of Jura, Colonsay and Kintyre.[154] Amongst its distinctive phonological features are the shift from long /aː/ to /ɛː/, a high degree of retention of long /eː/, the shift of dark /l̪ˠ/ to /t̪/, the lack of intrusive /t̪/ in sr groups (for example /s̪ɾoːn/ "nose" rather than /s̪t̪ɾoːn/)[155] and the retention of the unlenited past-tense particle d' (for example, d'èirich "rose" instead of dh'èirich).[156] It sits within a group of lexical isoglosses (i.e. words distinctive to a certain area) with strong similarities to southern Gaelic and northern Irish dialects. Examples are dhuit "to you" (instead of the more common dhut),[157] the formula gun robh math agad "thank you" (instead of the more common mòran taing or tapadh leat but compare Irish go raibh maith agat),[158] mand "able to" (instead of the more common urrainn)[159] or deifir "hurry" (instead of the more common cabhag, Irish deifir).[160]

Religion

Associated with various Islay churches are cupstones of uncertain age; these can be seen at Kilchoman Church, where the carved cross there is erected on one, and at Kilchiaran Church on the Rhinns. In historic times some may have been associated with pre-Christian wishing ceremonies or pagan beliefs in the "wee folk".[161]

The early pioneers of Christianity in Dál Riata were Columba of Iona and Moluag of Lismore.[162] The legacy of this period includes the 8th century Kildalton Cross, Islay's "most famous treasure",[163] carved out of local epidiorite.[164] A carved cross of similar age, but much more heavily weathered can be found at Kilnave,[165] which may have served as a site of lay worship.[166] Although the first Norse settlers were pagan, Islay has a substantial number of sites of drystone or clay-mortared chapels with small burial grounds from the later Norse era.[167] In the 12th century the island became part of the Diocese of Sodor and the Isles, which was re-established by King Olaf Godredsson.[168] The diocese fell within the jurisdiction of the Archdiocese of Nidaros and there were four principal churches on Islay in the Norwegian prestegjeld model: Kilnaughton, Kildalton, Kilarrow and Kilmany.[169] In 1472 Islay became part of the Archdiocese of St Andrews.[169]

Archibald Campbell, 5th Earl of Argyll was a strong supporter of the Reformation, but there is little evidence that his beliefs were greeted with much enthusiasm by the islanders initially. At first there were only two reformed churches but in 1642 three parishes were created, based at Kilchoman, Kilarrow and a new church at Dunyvaig. By the end of the century there were seven churches including one on Nave Island.[170] Kilarrow Parish Church is round, as local folklore has it, to leave no corner for the devil to hide in. This "architectural gem" was constructed in 1767 by Daniel Campbell, the laird of Islay.[171] The kirk on the Rhinns of Islay is St Kiaran's, located just outside the village of Port Charlotte and Port Ellen is served by St John's. There are a variety of other Church of Scotland churches and various other congregations on the island. Baptists meet in Port Ellen and in Bowmore, the Scottish Episcopal Church of St. Columba is located in Bridgend and the Islay Roman Catholic congregation also uses St. Columba's for its services.[172]

Media and the arts

Islay was featured in some of the scenes of the 1954 film The Maggie,[173] and the 1942 documentary "Coastal Command" was partly filmed in Bowmore.[174]

In 1967–68, folk-rock singer Donovan included "The Isle of Islay" in his album, A Gift from a Flower to a Garden, a song praising the pastoral beauties of the island.[Note 12] "Westering Home" is a 20th-century Scottish song about Islay written by Hugh S. Roberton, derived from an earlier Gaelic song.[176][177]

In the 1990s the BBC adaptation of Para Handy was partly filmed in Port Charlotte and Bruichladdich and featured a race between the Vital Spark (Para Handy's puffer) and a rival along the length of Loch Indaal. In 2007, parts of the BBC Springwatch programme were recorded on Islay with Simon King being based on Islay. The British Channel 4 archaeological television programme Time Team excavated at Finlaggan, the episode being first broadcast in 1995.[178][179][180]

In 2000, Japanese author Murakami Haruki visited the island to sample seven single malt whiskies on the island and later wrote a travel book called If our language were whiskey.

Wildlife

Islay is home to many species of wildlife and is especially known for its birds. Winter-visiting barnacle goose numbers have reached 35,000 in recent years with as many as 10,000 arriving in a single day. There are also up to 12,000 Greenland white-fronted geese, and smaller numbers of brent, pinkfooted and Canada geese are often found amongst these flocks. Other waterfowl include whooper and mute swans, eider duck, Slavonian grebe, goldeneye, long-tailed duck and wigeon.[181] The elusive corncrake and sanderling, ringed plover and curlew sandpiper are amongst the summer visitors.[181] Resident birds include red-billed chough, hen harrier, golden eagle, peregrine falcon, barn owl, raven, oystercatcher and guillemot.[181] The re-introduced white-tailed sea eagle is now seen regularly around the coasts.[182] In all, about 105 species breed on the island each year and between 100 and 120 different species can be seen at any one time.[181]

A population of several thousand red deer inhabit the moors and hills. Fallow deer can be found in the southeast, and roe deer are common on low-lying ground. Otters are common around the coasts along Nave Island, and common and grey seals breed on Nave Island. Offshore, a variety of cetaceans are regularly recorded including minke whales, pilot whales, killer whales and bottle-nosed dolphins. The only snake on Islay is the adder and the common lizard is widespread although not commonly seen.[183] The island supports a significant population of the marsh fritillary along with numerous other moths and butterflies.[184] The mild climate supports a diversity of flora, typical of the Inner Hebrides.[185]

Notable natives

- John Francis Campbell, authority on Celtic folklore and joint inventor of the Campbell–Stokes recorder. The son of Daniel Campbell of Shawfield, his father's bankruptcy prevented him inheriting the Islay estate. There is a monument commemorating him at Bridgend.[186]

- Glenn Campbell, Scottish political reporter for the BBC, was brought up on Islay and attended Islay High School.[187]

- Alistair Carmichael, the Liberal Democrat Deputy Chief Whip, was born on Islay to hill-farming parents. He has represented Orkney and Shetland at Westminster since 2001.[188]

- The Islay-born Reverend Donald Caskie (1902–1983) became known as the "Tartan Pimpernel" for his exploits in France during World War II.[189]

- John Crawfurd was born on Islay in 1783 and during a long career as a colonial administrator he became governor of Singapore. He also wrote a number of books including Journal of an Embassy from the Governor General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China (1828).[190]

- David MacIntyre from Portnahaven, recipient of the Victoria Cross.[191]

- General Alexander McDougall, a figure in the American Revolution and the first president of the Bank of New York, was born in Kildalton in 1731.[192]

- George Robertson, formerly secretary-general of NATO and British Defence Secretary. In 1999 he was made Lord Robertson of Port Ellen.[193]

- Sir William Stewart (born 1935) steered a course from Bowmore junior school to become the UK government’s Chief Scientific Adviser in the late 1980s and early 1990s.[194]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) has a table of Scottish "islands arranged in order of magnitude" that lists Islay as fifth in rank, although this excludes Skye as it is a bridged island and includes South Uist as fourth on the grounds that it is connected to other islands such as Benbecula and North Uist by causeways that give it a large area.[10] Rick Livingstone’s Tables provide all the relevant area data although the information is not ranked.[11] Ireland is the largest of the islands surrounding Great Britain and Anglesey the sixth largest.

- ↑ Mac an Tàilleir (2003) suggests that "if this is a Gaelic name it may be 'flank shaped'."[17]

- ↑ Banrìgh Innse Gall is literally "Queen of the islands of the foreigners" and Banrìgh nan Eilean means "Queen of the islands".

- ↑ The Rhinns complex, named after the Islay peninsula which hosts its largest outcrop, is predominantly Palaeoproterozoic syenitic gneiss. It lies unconformably beneath the Colonsay Group.[33]

- ↑ At the time this Ahrensburgian flint was the oldest find in Scotland[51] but a subsequent discovery at Biggar predates it by over a millennium.[52]

- ↑ Various locations have been suggested for the battle, including west of the Rinns and north of Rubh' a' Mhail. Marsden (2008) concludes that a location at the north end of the Sound of Islay is most likely.[74]

- ↑ Loch Finlaggan has two main islands. Eilean Mòr was probably an early Christian centre and was fortified in the 13th and 14th centuries.[88][89]

- ↑ While the Lordship itself did not survive, the title did; today, the heir to the British throne, who is known as the Prince of Wales in all other parts of the British Commonwealth, bears the title Lord of the Isles within Scotland.[94]

- ↑ Martin wrote of the "isle Finlagan", that it is "famous for being once the court in which the great Macdonald, King of the Isles, had his residence; his houses, chapel, etc., are now ruinous. His guards de corps, called Lucht-taeh, kept guard on the lake side nearest to the isle; the walls of their houses are still to be seen there. The High Court of Judicature, consisting of fourteen, sat always here; and there was an appeal to them from all the Courts in the isles: the eleventh share of the sum in debate was due to the principal judge. There was a big stone of seven feet square, in which there was a deep impression made to receive the feet of Macdonald; for he was crowned King of the Isles standing in this stone, and swore that he would continue his vassals in the possession of their lands, and do exact justice to all his subjects: and then his father’s sword was put into his hand. The Bishop of Argyll and seven priests anointed him king, in presence of all the heads of the tribes in the isles and continent, and were his vassals; at which time the orator rehearsed a catalogue of his ancestors, etc."[95]

- ↑ With regard to the castles of Islay Monro wrote: "In this iyle there is strenths castells; the first is callit Dunowaik, biggit on ane craig at the sea side, on the southeist part of the countery pertaining to the Clandonald of Kintyre; second is callit the castle of Lochgurne, quhilk is biggit ill ane iyle within the said fresche water loche far fra land, pertaining of auld to the Clandonald of Kintyre, now usurped be M’Gillayne of Doward. Ellan Forlagan, in the middle of Ila, ane faire iyle in fresche water.[97]

- ↑ The structure was built for Sir Hugh Campbell of Cawdor and is now used as a hotel.[102] It is a Category A listed building.[103]

- ↑ It is claimed that Donovan wrote the song after being arrested for possession of marijuana and that "I had to leave, I had to get away from the publicity, so I took a plane north to Scotland, and on a northern island I found the peace, and I wrote this song."[175]

Footnotes

- 1 2 Gammeltoft 2007, p. 487

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Haswell-Smith 2004, p. 41

- 1 2 Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- ↑ Haswell-Smith 2004, p. 42

- 1 2 3 National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013) (pdf) Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland - Release 1C (Part Two). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland’s inhabited islands". Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ↑ National Records of Scotland. "Table KS101SC - Usual Resident Population, all people; Settlement/Locality 2010; Port Ellen". Scotland's Census 2011. From the main page select Results, Standard Outputs, year 2011, table KS101SC,area type locality 2010. On the map click Bowmore and Port Ellen for comparison.

- 1 2 Newton 1995, p. 11

- ↑ Newton 1995, p. 20

- ↑ Newton 1995, p. 31

- ↑ Haswell-Smith 2004, p. 502

- ↑ Rick Livingstone’s Tables of the Islands of Scotland (pdf) Argyll Yacht Charters. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ↑ Caldwell & 2011, p. 58

- 1 2 3 Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2004) 1901-2001 Gaelic in the Census (PowerPoint) Linguae Celticae. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 37

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 45

- ↑ Watson (1994) p. 85-86

- 1 2 3 Mac an Tàilleir 2003, p. 67

- ↑ "Atlas of Scotland 1654 - ILA INSVLA - The Isle of Ila". Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Atlas of Scotland 1654 - IVRA INSVLA - The Isle of Jura". Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ↑ "Visitors". Highlands and Islands Airports. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ↑ Caldwell 2011, p. 91

- ↑ Jennings & Kruse 2009a, pp. 83–84

- ↑ King & Cotter 2012, p. 4

- ↑ King & Cotter 2012, p. 6

- ↑ King & Cotter 2012, pp. 34,36–43

- ↑ King & Cotter 2012, p. 31

- ↑ Murray (1966) pp. 22–23

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Get-a-map: Sheet 60 Islay (Map). Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ↑ Murray (1966) p. 32

- ↑ Newton 1995, p. 42

- ↑ Murray (1966) p. 30

- 1 2 Caldwell 2011, p. xxv

- 1 2 J.S. Daly; R.j. Muir; R.A. Cliff (1991). "A precise U-Pb zircon age for the Inishtrahull syenitic gneiss, County Donegal, Ireland". Journal of the Geological Society. Geological Society. 148 (4): 639–642. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.148.4.0639. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ↑ R.J. Muir; W.R. Fitches; A.J. Maltman; M.R. Bentley (1994). "Precambrian rocks of the southern Inner Hebrides—Malin Sea region: Colonsay, west Islay, Inishtrahull and Iona". In Harris A.L. & Gibbons W. A Revised Correlation of Precambrian Rocks in the British Isles. Special Report. 22 (2 ed.). London: Geological Society. pp. 54–56. ISBN 9781897799116. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ↑ Gillen 2003, p. 65

- ↑ Haswell-Smith 2004, p. 47

- 1 2 "Islay Geology". Islay Natural History Trust. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ↑ Strachan, R. A, Smith, M., Harris, A. L., Fettes, D. J. "The Northern Highland and Grampian Terranes" in Trewin 2002, p. 96

- ↑ Thomas, Christopher W.; Graham, Colin M.; Ellam, Robert M.; Fallick, Anthony E. "Sr chemostratigraphy of Neoproterozoic Dalradian limestones of Scotland and Ireland: constraints on depositional ages and time scales" (pdf). 161. Journal of the Geological Society: 229–242. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ↑ "Jura Earthquake 3 May 1998". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ↑ Keay & Keay 1994, p. 547

- ↑ Mithen 2006, p. 197

- ↑ Caldwell 2011, p. 4

- 1 2 "Regional mapped climate averages: W Scotland". Met office. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ↑ "UK mapped climate averages". Met office. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ↑ "Weather". Islayjura.com. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ↑ Newton 1995, p. 9

- 1 2 "The 30 year average for Islay". Islay Info. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ↑ Newton 1995, p. 12

- ↑ Mithen 2006, pp. 197–98

- ↑ Moffat 2005, p. 42

- ↑ "Howburn Farm: Excavating Scotland’s first people" Current Archaeology. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev (9 October 2015) "Swine team: pigs help uncover ice age tools on Scottish island" The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 Oct 2015.

- ↑ "Ice Age tools found on Islay thanks to herd of pigs". (9 October 2015) BBC News Retrieved 11 Oct 2015.

- ↑ Storrie (1997) p. 28

- ↑ Jupp 1994, p. 10

- ↑ Storrie (1997) p. 29

- ↑ Jupp 1994, p. 11

- ↑ Newton 1995, p. 26

- ↑ Caldwell 2011, p. 17

- 1 2 Caldwell 2011, pp. 137–38

- ↑ Armit, Ian "The Iron Age" in Omand (2006) pp. 52–53

- ↑ Woolf (2012) p. 1

- 1 2 Caldwell (2011) pp. 21–22

- ↑ Rodger 1997, p. 5

- 1 2 3 Graham-Campbell & Batey 1998, p. 89

- ↑ Jennings & Kruse 2009b, p. 140

- ↑ Jennings & Kruse 2009a, p. 86

- 1 2 Duffy 2004, Godred Crovan (d. 1095)

- ↑ MacDonald 2007, p. 62

- ↑ Duffy 1992, p. 108

- ↑ Woolf (2005) p. 13

- ↑ Islay, Carragh Bhan, Canmore, retrieved 1 August 2013.

- 1 2 Marsden (2008) p. 84

- ↑ Caldwell (2011) p. 31

- ↑ Gregory 1881, pp. 9–17

- ↑ Hunter 2000, pp. 110–111

- ↑ Woolf, Alex "The Age of the Sea-Kings: 900–1300" in Omand (2006) pp. 108–09

- ↑ Gregory 1881, p. 24

- ↑ Gregory 1881, pp. 26–27

- ↑ Lee 1920, p. 82

- 1 2 3 Oram, Richard "The Lordship of the Isles, 1336–1545" in Omand (2006) pp. 124–26

- 1 2 Hunter 2000, p. 127

- ↑ Oram, Richard "The Lordship of the Isles, 1336–1545" in Omand (2006) p. 123

- ↑ Caldwell (2011) p. 38

- ↑ Casey, Dan: Finlaggan and the Lordship IslayInfo.com Retrieved 2010-10-05.

- ↑ Bord, Janet & Colin (1976). The Secret Country. London: Paul Elek. ISBN 0-236-40048-7; pp. 66-67

- ↑ Caldwell (2011) p. 169

- ↑ Caldwell (2011) p. 20

- ↑ David Ross (10 May 2007). "Gaelic documents may return north". The Herald. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ↑ Oram, Richard "The Lordship of the Isles, 1336–1545" in Omand (2006) p. 132

- ↑ Caldwell (2011) p. 59

- ↑ Caldwell, David (April 1996) "Urbane savages of the Western Isles". British Archaeology. No 13. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ↑ Dunbar, J. (1981) The Lordship of the Isles in The Middle Ages in the Highlands. Inverness Field Club. ISBN 978-0-9502612-1-8

- ↑ Martin 1703, p. 240, Jurah

- ↑ Caldwell 2011, p. 61

- 1 2 Monro 1774, pp. 12–13, 55. Ila

- ↑ Caldwell 2011, pp. 62–64

- ↑ Haswell-Smith 2004, pp. 42–43

- ↑ Caldwell 2011, p. 68

- ↑ Caldwell 2011, pp. 66,74

- ↑ "Islay House".

- ↑ "Islay House". Historic Scotland. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ↑ Morrison, Alex "Rural Settlement: an Archaeological Viewpoint" in Omand (2006) p. 110

- 1 2 Caldwell 2011, pp. 75–76

- ↑ Caldwell 2011, p. 70

- ↑ "Campbell, Daniel (1671?–1753)" Dictionary of National Biography (1904). Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- 1 2 Caldwell 2011, p. 79

- ↑ Duncan, P. J. "The Industries of Argyll: Tradition and Improvement" in Omand (2006) p. 151

- ↑ Duncan, P. J. "The Industries of Argyll: Tradition and Improvement" in Omand (2006) pp. 152–4

- ↑ Duncan, P. J. "The Industries of Argyll: Tradition and Improvement" in Omand (2006) pp. 156–57

- ↑ "The Clearances on Islay in the 1800s" IslayInfo. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ "Highland Clearances". Cranntara. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ Baird 1995, pp. 57–58

- ↑ Baird 1995, pp. 80–83

- ↑ "The Oa Peninsula". IslayInfo. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ CWGC Cemetery report, Kilchoman Military Cemetery.

- ↑ "No 119 Squadron RAF". RAF Commands. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ↑ "422 Faces". Castle Archdale, Northern Ireland Coastal Command. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ "Islay, Saligo, Chain Home and Type 7000 Chain Radar Station". Scotland's Places. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ "Islay, Kilchirian, Radar Station". Canmore. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- 1 2 Caldwell (2011) p. 95

- ↑ "Fishing on Islay – Where to catch Brown Trout". IslayInfo. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- 1 2 "Isle of Islay" Fishing-Argyll. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ↑ Newton 1995, p. 82

- ↑ "Islay and the Sea – Geography and History". IslayInfo. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ↑ "The Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009". The National Archives. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ Newton 1995, p. 32

- ↑ "Whisky Regions & Tours". Scotch Whisky Association. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "Islay Whisky" information-britain.co.uk. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ↑ "Home". Islay Whisky. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "Kilchoman Scotch Whisky Distillery". ScotchWhisky.net. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- 1 2 Newton 1995, p. 33

- 1 2 "Port Charlotte Distillery". IslayInfo. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ Keay & Keay 1994, p. 548

- ↑ "The Isle of Islay". Visit Scotland. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "Islay Malt Whisky & Islay Distilleries". IslayInfo. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "Visit Finlaggan". The Finlaggan Trust. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ Tom Heath. "The Construction, Commissioning and Operation of the LIMPET Wave Energy Collector" (pdf). Wavegen. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ↑ "Islay to get major tidal power scheme" (17 March 2011) BBC Scotland. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ↑ "Islay Travel and Local Transport Information". IslayInfo. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "MV Finlaggan" (pdf). Caledonian MacBrayne. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ "Travelling to Islay & Jura". Visit Islay Jura. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ "Rinns of Islay". Northern Lighthouse Board. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ↑ "Ruvaal". Northern Lighthouse Board. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ↑ Newton 1995, p. 16

- ↑ "Shetland Times Retains Newspaper Of The Year Award". Highland Council. 18 January 2007. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ↑ "Islay & Jura Council for Voluntary Service – Bowmore" Firstport. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ↑ "Ales from the Isle of Malts". Islay Ales. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ↑ "An open door to Gaelic language and culture". Ionad Chaluim Chille Ìle. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ↑ "About Us". Iomairt Chille Chomain. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ↑ "Iomairt Chille Chomain". DTA Scotland. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ↑ "Boost for Islay Gaelic centre" (11 September 2001) Scottish Government. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ↑ Grannd 2000, pp. 61–65

- ↑ Grannd 2000, pp. 14, 73; 54–55, 139; 59, 146; 51, 134

- ↑ Grannd 2000, p. 135

- ↑ Grannd 2000, pp. 17, 78

- ↑ Grannd 2000, pp. 22, 86

- ↑ Grannd 2000, pp. 26–27, 94

- ↑ Grannd 2000, pp. 33, 107

- ↑ Morris, Ronald W. B. (1969) "The Cup-and-Ring Marks and Similar Sculptures of Scotland: a Survey of the Southern Counties, Part II." Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 100 pp. 53, 55, 63

- ↑ Fisher, Ian "The early Christian Period" in Omand (2006) p. 71

- ↑ Newton 1995, p. 37

- ↑ "Kildalton Great Cross" RCAHMS. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ↑ "Archaeology Notes on Kilnave". RCAHMS. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ↑ Fisher, Ian "The early Christian Period" in Omand (2006) p. 82

- ↑ Fisher, Ian "The early Christian Period" in Omand (2006) p. 83

- ↑ Bridgland, Nick "The Medieval Church in Argyll" in Omand (2006) p. 86

- 1 2 Bridgland, Nick "The Medieval Church in Argyll" in Omand (2006) pp. 88–9

- ↑ Caldwell 2011, pp. 68–69

- ↑ Newton 1995, pp. 20–21

- ↑ "Churches and Services on the Isle of Islay." IslayInfo. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ↑ The Maggie Imdb. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ↑ "Filming locations for "Coastal Command"". IMDb. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ↑ "Isle of Islay" Donovan Unofficial. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ↑ "Westering Home". Scottish Poetry Library. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ↑ "Westering Home". Celtic Arts Center. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ↑ "Springwatch". BBC. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ↑ "Mid-Argyll, Kintyre & Islay". Visit Scotland. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ↑ "Time Teak: Series 2". Channel 4. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Birdwatching on Islay". Scottish Ornithologists' Club/Scottish Bird News. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ "Islay and Jura". Naturetrek. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ "Mammals, Reptiles and Amphibians". Islay Natural History Trust. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ "Islay Wildlife Records – Moths and Butterflies Index". Islay Natural History Trust. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ "Islay Wildlife Records – Flowering plants Index". Islay Natural History Trust. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ Haswell-Smith 2004, p. 43

- ↑ "Meet presenter Glenn Campbell". BBC News. 2 March 2003. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ↑ "Alistair Carmichael" Scottish Liberal Democrats. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ↑ "Our man in Marseilles". (27 December 2001) Edinburgh. The Scotsman. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ↑ Turnbull, C. M. (2004) "Crawfurd, John (1783–1868), orientalist and colonial administrator". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ↑ "Grave Location For Holders of the Victoria Cross in the City Of Edinburgh" Archived 25 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine.. Prestel. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ "McDougall, Alexander, (1731–1786)". United States Congress. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ↑ "NATO Secretary General (1999–2003) The Rt. Hon. Lord Robertson of Port Ellen". Who is who at NATO?. NATO. 6 January 2004. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ↑ "Sir William Stewart Doctor of Science". Edinburgh Napier University. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

General references

- Baird, Bob (1995). Shipwrecks of the West of Scotland. Glasgow: Nekton Books. ISBN 1-897995-02-4.

- Caldwell, David H. (2011). Islay, Jura and Colonsay: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-961-9.

- Duffy, Seán (1992). "Irishmen and Islesmen in the Kingdom of Dublin and Man 1052–1171". Ériu. 43 (43): 93–133. JSTOR 30007421.

- —— (2004). "Godred Crovan (d. 1095)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gammeltoft, Peder (2007). "Scandinavian Naming-Systems in the Hebrides—A Way of Understanding how the Scandinavians were in Contact with Gaels and Picts?". In Ballin-Smith, Beverley; Taylor, Simon; Williams, Gareth. West over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. Leiden: Brill.

- Gillen, Con (2003). Geology and landscapes of Scotland. Harpenden: Terra Publishing. ISBN 1903544092.

- Graham-Campbell, James; Batey, Colleen E. (1998). Vikings in Scotland: An Archaeological Survey. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0641-2.

- Grannd, Seumas (2000). The Gaelic of Islay: A Comparative Study. Scottish Gaelic Studies Monograph Series 2. Department of Celtic, University of Aberdeen. ISBN 0-9523911-4-7.

- Gregory, Donald (1881). The history of the Western Highlands and Isles of Scotland, from A.D. 1493 to A.D. 1625, with a brief introductory sketch, from A.D. 80 to A.D. 1493 (2nd ed.). London; Glasgow: Hamilton, Adams & Co.; Thomas D. Morison.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Hunter, James (2000). Last of the Free: A History of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Edinburgh: Mainstream. ISBN 1-84018-376-4.

- Jennings, Andrew; Kruse, Arne (2009a). "One Coast-Three Peoples: Names and Ethnicity in the Scottish West during the Early Viking period". In Woolf, Alex. Scandinavian Scotland – Twenty Years After: The Proceedings of a Day Conference held on 19 February 2007. St John's House Papers No 12. St. Andrews: University of St. Andrews, Committee for Dark Age Studies. pp. 75–102. ISBN 978-0-9512573-7-1.

- ——; —— (2009b). "From Dál Riata to the Gall-Ghàidheil". Viking and Medieval Scandinavia. 5: 123–149.

- Jupp, Clifford (1994). The History of Islay: From earliest times to 1848. Port Charlotte: Museum of Islay Life. ASIN B0000COS6B.

- Keay, John; Keay, Julie, eds. (1994). Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland (1st ed.). Hammersmith, London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255082-2.

- King, Jacob; Cotter, Michelle (2012). Place-names in Islay and Jura. Perth: Scottish Natural Heritage.

- Lee, Henry James (1920). History of the clan Donald, the families of MacDonald, McDonald and McDonnell. New York: Polk and Company.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003). "Ainmean-àite" [Placenames: Faddoch – Jura] (pdf). www.scottish.parliament.uk/gd/visitandlearn/40900.aspx (in Scottish Gaelic and English). Pàrlamaid na h-Alba / Parliament of Scotland. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- MacDonald, R. Andrew (2007). Manx kingship in its Irish Sea setting, 1187–1229: King Rognvaldr and the Crovan dynasty. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-047-2.

- Martin, Martin (1703). A Description of The Western Islands of Scotland (1st ed.). London: Andrew Bell.

- Mithen, Steven (2006). After the ice: a global human history, 20,000–5000 BC. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01570-3.

- Moffat, Alistair (2005). Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Monro, Donald (1774) [1773]. "A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland, Called Hybrides". A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland, Called Hybrides (and other works). Edinburgh: William Auld. Date of composition without publishing is 1549. Date of first independent publication is 1582.

- Murray, W. H. (1966). The Hebrides. London: Heinemann.

- Newton, Norman (1995). Islay. Devon: David & Charles PLC. ISBN 0-907115-90-X.

- Omand, Donald (ed.) (2006) The Argyll Book. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-480-5

- Rodger, N. A. M. (1997). The Safeguard of the Sea: A Naval History of Britain. Volume One 660–1649. London: Harper Collins.

- Storrie, Margaret (1997). Islay: Biography of an Island. Colonsay: House of Lochar. ISBN 0-907651-03-8.

- Trewin, Nigel H. (2002). The Geology of Scotland (4th ed.). Bath: The Geology Society. ISBN 1862391262.

- Watson, W. J. (1994) The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-323-5. First published 1926.

- Woolf, Alex (2012) "Ancient Kindred? Dál Riata and the Cruthin". St Andrews University. Academia.edu. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

External links

- Map sources for Islay

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Islay. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Islay. |

- "Isle of Islay". Islay Info. 2014. Provides additional information on the demographics and culture of Islay and the Hebrides.

- "The Islay Natural History Trust". Port Charlotte, Islay: The Natural History Centre. Provides additional detailed information on the terrain and the species inhabiting niches on Islay.

- Van Ells, Mark D. (June 13, 2013). "Isle of Islay: Cliffs Prove Deadly in WWI Shipwrecks". Stars & Stripes. Specialized information on the maritime hazards of the coastline.

Coordinates: 55°46′N 6°9′W / 55.767°N 6.150°W