Irena Sendler

| Irena Sendler | |

|---|---|

|

Sendler c. 1942 | |

| Born |

Irena Krzyżanowska 15 February 1910 Otwock, Poland |

| Died |

12 May 2008 (aged 98) Warsaw, Poland |

| Occupation | Social worker, humanitarian |

| Spouse(s) |

Mieczyslaw Sendler (1931–1947; divorced) Stefan Zgrzembski (1947–1959; divorced; 3 children) Mieczyslaw Sendler (1960s; divorced) |

| Parent(s) |

Stanisław Krzyżanowski Janina Krzyżanowska |

| Righteous Among the Nations |

|---|

| Notable individuals |

| By country |

Irena Sendler (née Krzyżanowska), also referred to as Irena Sendlerowa in Poland, nom de guerre "Jolanta" (15 February 1910 – 12 May 2008),[1] was a Polish nurse, humanitarian, and social worker who served in the Polish Underground in German-occupied Warsaw during World War II, and was head of the children's section of Żegota,[2][3] the Polish Council to Aid Jews (Polish: Rada Pomocy Żydom), which was active from 1942 to 1945.

Assisted by some two dozen other Żegota members, Sendler smuggled approximately 2,500 Jewish children out of the Warsaw Ghetto and then provided them with false identity documents and shelter outside the Ghetto, saving those children from the Holocaust.[4] With the exception of diplomats who issued visas to help Jews flee Nazi-occupied Europe, Sendler saved more Jews than any other individual during the Holocaust.[5]

The German occupiers eventually discovered her activities and she was arrested by the Gestapo, tortured, and sentenced to death, but she managed to evade execution and survive the war. In 1965, Sendler was recognised by the State of Israel as Righteous among the Nations.[6] Late in life, she was awarded the Order of the White Eagle, Poland's highest honour, for her wartime humanitarian efforts.

Biography

Sendler was born as Irena Krzyżanowska on 15 February 1910 in Warsaw[7] to Dr. Stanisław Krzyżanowski, a physician, and his wife, Janina.[8] She grew up in Otwock, a town about 15 miles southeast of Warsaw, where there was a vibrant Jewish community.[9] Her father died in February 1917 from typhus contracted while treating patients.[10] After his death, Jewish community leaders offered to help her mother pay for Sendler's education, though her mother declined their assistance.[8] Sendler studied Polish literature at Warsaw University, and joined the Polish Socialist Party.[8] She opposed the ghetto-bench system that existed at some pre-war Polish universities and defaced her grade card. As a result of this public protest, she was suspended from the University of Warsaw for three years.[11]

She married Mieczysław Sendler in 1931,[8] but they divorced in 1947.[12] She then married Stefan Zgrzembski, a Jewish friend from her university days, by whom she had three children, Janina, Andrzej (who died in infancy), and Adam (who died of heart failure in 1999). In 1959 she divorced Zgrzembski and remarried her first husband, Mieczysław Sendler. They eventually divorced again.[13]

World War II

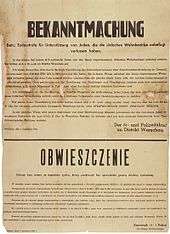

Sendler moved to Warsaw prior to the outbreak of World War II, and worked for municipal Social Welfare departments.[8] She began aiding Jews soon after the German invasion in 1939,[8] by leading a group of co-workers who created more than 3,000 false documents to help Jewish families.[14] This work was done at huge risk, as — since October 1941 — giving any kind of assistance to Jews in German-occupied Poland was punishable by death, not just for the person who was providing the help but also for their entire family or household. Poland was the only country in German-occupied Europe in which such a death penalty was applied.[15]

In August 1943, Sendler, by then known by her nom de guerre Jolanta, was nominated by Żegota, the underground organization also known as the Council to Aid Jews, to head its Jewish children's section.[14] As an employee of the Social Welfare Department, she had a special permit to enter the Warsaw Ghetto to check for signs of typhus, a disease the Germans feared would spread beyond the Ghetto.[16] During these visits, she wore a Star of David as a sign of solidarity with the Jewish people.[17] Under the pretext of conducting inspections of sanitary conditions within the Ghetto, Sendler and her co-workers smuggled out babies and small children, sometimes in ambulances and trams, sometimes hiding them in packages and suitcases, and using various other means.[18]

Jewish children were placed with Polish Christian families, the Warsaw orphanage of the Sisters of the Family of Mary, or Roman Catholic convents such as the Little Sister Servants of the Blessed Virgin Mary Conceived Immaculate.[19] Sendler worked closely with a group of about 30 volunteers, mostly women, who included Zofia Kossak-Szczucka, a resistance fighter and writer, and Matylda Getter, Mother Provincial of the Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary.[20] The children were given fake Christian names and taught Christian prayers in case they were tested.[21] Sendler was determined to prevent the children from losing their Jewish identities, and kept careful documentation listing the children's fake Christian names, their given names, and their current location.[21]

According to American historian Debórah Dwork, Sendler was "the inspiration and the prime mover for the whole network that saved those 2,500 Jewish children."[22] About 400 of the children were directly smuggled out by Sendler herself.[22] She and her co-workers buried lists of the hidden children in jars in order to keep track of their original and new identities. The aim was to return the children to their original families when the war was over.[11]

In 1943, Sendler was arrested by the Gestapo and severely tortured. As they ransacked her house, Sendler tossed the lists of children to her friend, who hid the list in her loose clothing.[21] Should the Gestapo access this information, all children would be compromised, but eventually her friend was never searched. The Gestapo beat Sendler brutally upon her arrest, fracturing her feet and legs in the process. Despite this, she refused to betray any of her comrades or the children they rescued, and was sentenced to death by firing squad. Żegota saved her life by bribing the guards on the way to her execution.[17] After her escape, she hid from the Germans, but returned to Warsaw under a fake name and continued her involvement with the Żegota.[8] During the Warsaw Uprising, she worked as a nurse in a public hospital, where she hid five Jews.[8] She continued to work as a nurse until the Germans left Warsaw, retreating before the advancing Soviet troops.[8]

After the war, she and her co-workers gathered all of the children's records with the names and locations of the hidden Jewish children and gave them to their Żegota colleague Adolf Berman and his staff at the Central Committee of Polish Jews. Almost all of the children's parents had been killed at the Treblinka extermination camp or had gone missing.[17][8]

Communist Poland

After the war, Sendler was imprisoned from 1948 to 1949 and brutally interrogated by the communist secret police (Urząd Bezpieczeństwa) due to her connections with Poland's principal resistance organisation, the Home Army (AK), which was loyal to the wartime Polish government in exile.[23][24] As a result, she gave birth prematurely to her son, Andrzej, who did not survive.[8][10][23] Although she was eventually released and agreed to join the communist party (PZPR),[25] her ties to the AK meant that she was never made into a hero.[10][23] In fact, in 1965 when Sendler was recognized by Yad Vashem as one of the Polish Righteous among the Nations,[17] Poland's communist government did not allow her to travel abroad at that time to receive the award in Israel; she was able to do so only in 1983.[8][26]

She was later employed as a teacher and vice-director in several Warsaw medical schools, and worked for the Ministries of Education and Health.[24][27] She was also active in various social work programs. She helped organize a number of orphanages and care centers for children, families and the elderly, as well as a center for prostitutes in Henryków.[24]

Sendler was forced into early retirement for her public declarations of support for Israel in the 1967 Israeli-Arab War (countries of the Soviet-controlled Eastern Bloc, including Poland, broke off diplomatic relations with Israel in the aftermath of this war).[8] Sendler resigned her PZPR membership following the events of March 1968 in Poland.[23][25]

In 1980 she joined the Solidarity movement.[8]

Later life

Sendler lived in Warsaw for the remainder of her life. She died on 12 May 2008, aged 98, and is buried in Warsaw's Powązki Cemetery.[18][25][28][29]

Recognition and remembrance

In 1965, Sendler was recognized by Yad Vashem as one of the Polish Righteous among the Nations[30][31] and a tree was planted in her honor at the entrance to the Avenue of the Righteous.[32] There was no further public recognition of her wartime resistance and humanitarian work until after the end of communist rule in Poland.

In 1991, Sendler was made an honorary citizen of Israel.[33] On 12 June 1996, she was awarded the Commander's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta.[34][35] She received a higher version of this award, the Commander's Cross with Star, on 7 November 2001.[36]

Nevertheless, Irena Sendler's achievements remained largely unknown to the world until 1999, when students at a high school in Uniontown, Kansas, along with their teacher Norman Conard, produced a play based on their research into her life story, which they called Life in a Jar. It was a surprising success, staged over 200 times in the United States and abroad, and significantly contributed to publicising Sendler's history worldwide.[37] In March 2002, B’nai Jehudah Temple of Kansas City presented Sendler, Conard and the students who produced the play with its annual award “for contributions made to saving the world” (Tikkun Olam Award).[38] The play was adapted for television as The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler (2009), directed by John Kent Harrison, in which Sendler was portrayed by actress Anna Paquin.[39][40][41]

In 2003, Pope John Paul II sent Sendler a personal letter praising her wartime efforts.[42][43] On 10 November 2003, she received the Order of the White Eagle, Poland's highest civilian decoration,[44] and the Polish-American award, the Jan Karski Award "For Courage and Heart", given by the American Center of Polish Culture in Washington, D.C.[45]

In 2006, Polish NGOs Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej and Stowarzyszenie Dzieci Holocaustu, the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Life in a Jar Foundation established the "Irena Sendler's Award: For Repairing the World" (pl:Nagroda imienia Ireny Sendlerowej „Za naprawianie świata”), awarded to Polish and American teachers.[46][47] The Life in a Jar Foundation is a foundation dedicated to promoting the attitude and message of Irena Sendler.[47]

In 2007, she was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.[nb 1]</ref>[48][30][49][50] On 14 March 2007, Sendler was honoured by the Polish Senate,[51] and a year later, on 30 July, by the American Congress.[52] On 11 April 2007, she received the Order of the Smile; at that time she was the oldest recipient of the award.[53] In 2007 she became an honorary citizen of the cities of Warsaw and Tarczyn.

On the occasion of the Order of the Smile award, she mentioned that the award from children is among her favorite ones, along with the Righteous among the Nations award and the letter from the Pope.[54]

.jpg)

In April 2009 she was posthumously granted the Humanitarian of the Year award from The Sister Rose Thering Endowment,[55] and in May 2009, Sendler was posthumously granted the Audrey Hepburn Humanitarian Award.[56]

Around this time American filmmaker Mary Skinner filmed a documentary, Irena Sendler, In the Name of Their Mothers (Polish: Dzieci Ireny Sendlerowej), featuring the last interviews Sendler gave before her death. The film made its national U.S. broadcast premiere through KQED Presents on PBS in May 2011 in honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day[57] and went on to receive several awards, including the 2012 Gracie Award for outstanding public television documentaries.[58]

In 2013 the walkway in front of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw was named after Irena Sendler.[59]

In 2010 a memorial plaque commemorating Sendler was added to the wall of 2 Pawińskiego Street in Warsaw – a building in which she worked from 1932 to 1935. In 2015 she was honoured with another memorial plaque at 6 Ludwiki Street, where she lived from the 1930s to 1943.[60]

Several schools in Poland have also been named after her.[61]

Literature

In 2010, Polish historian, Anna Mieszkowska, wrote Irena Sendler: Mother of the Children of the Holocaust, a biography on Sendler[62] In 2011, Jack Mayer tells the story of the four Kansas school girls and their discovery of Irena Sendler in his novel, Life in a Jar: The Irena Sendler Project[61]

In 2016, a book about Sendler, Irena's Children, written by Tilar J. Mazzeo, was released by Simon and Schuster. A version adapted to be read by children was created by Mary Cronk Farell.[63]

Another children's picture book is Jars of Hope: How One Woman Helped Save 2,500 Children During the Holocaust, written by Jennifer Roy.

Gallery

Irena Sendler in 1942.

Irena Sendler in 1942. Irena Sendler in 1944.

Irena Sendler in 1944.- Irena Sendler's tree on the Avenue of the Righteous at Yad Vashem in Israel.

A Polish commemorative coin picturing Irena Sendler and fellow Holocaust resisters Zofia Kossak-Szczucka and Matylda Getter.

A Polish commemorative coin picturing Irena Sendler and fellow Holocaust resisters Zofia Kossak-Szczucka and Matylda Getter._RIP_(8403714206).jpg) A newspaper story about the death of Irena Sendler.

A newspaper story about the death of Irena Sendler..jpg) Irena Sendler's funeral.

Irena Sendler's funeral.- Irena Sendler's grave in Warsaw's Powązki Cemetery.

.jpg) The headstone on Irena Sendler's grave in Warsaw's Powązki Cemetery.

The headstone on Irena Sendler's grave in Warsaw's Powązki Cemetery..jpg) A memorial plaque on the wall of 2 Pawińskiego Street in Warsaw.

A memorial plaque on the wall of 2 Pawińskiego Street in Warsaw.- The walkway in front of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews has been named after Irena Sendler.

Aleja Ireny Sendlerowej.

Aleja Ireny Sendlerowej. Irena Sendler sculpture by Claudia Guderian, at the Irena Sendler School, Hamburg, Germany.

Irena Sendler sculpture by Claudia Guderian, at the Irena Sendler School, Hamburg, Germany. A bronze plaque in Piotrków Trybunalski telling some of her story.

A bronze plaque in Piotrków Trybunalski telling some of her story.- Irena Sendler boulevards in Białystok.

See also

- The Holocaust in Poland

- Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust

- Polish Righteous Among the Nations

- List of Poles: Holocaust resisters

- Individuals and groups assisting Jews during the Holocaust

- Henryk Sławik

Notes

- ↑ The official Nobel Peace Prize website states: "The statutes of the Nobel Foundation restrict disclosure of information about the nominations, whether publicly or privately, for 50 years." It further states: "In so far as certain names crop up in the advance speculations as to who will be awarded any given year's Prize, this is either sheer guesswork or information put out by the person or persons behind the nomination."

- ↑ Irena Sendler. An unsung heroine. Lest We Forget. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ↑ Mordecai Paldiel, The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust, Ktav Publishing House (January 1993), ISBN 0-88125-376-6

- ↑ Yad Vashem Shoa Resource Center, "Activites Żegota" PDF file, Żegota, page 4/34 of the Report.

- ↑ Baczynska, Gabriela (12 May 2008). Jon Boyle, ed. "Sendler, savior of Warsaw Ghetto children, dies". Reuters. Retrieved Sep 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Rethinking the Polish Underground". Yeshiva University News.

- ↑ Atwood, Kathryn (2011). Women Heroes of World War II. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. p. 48. ISBN 9781556529610.

- ↑ "Facts about Irena — Life in a Jar". Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Polscy Sprawiedliwi – Przywracanie Pamięci". sprawiedliwi.org.pl (in Polish).

- ↑ "Irena Sendler — Rescuer of the Children of Warsaw". www.chabad.org. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

- 1 2 3 "Biografia Ireny Sendlerowej". tak.opole.pl (in Polish). Zespół Szkół TAK im. Ireny Sendlerowej.

- 1 2 Staff writer (May 22nd 2008), The Economist obituary. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ↑ Anna Mieszkowska (January 2011). Irena Sendler: Mother of the Children of the Holocaust. Praeger. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-313-38593-3.

- ↑ "Irena Sendler: we tell you the story of a Holocaust heroine". Mail Online.

- 1 2 Irene Tomaszewski & Tecia Werblowski, Zegota: The Council to Aid Jews in Occupied Poland 1942–1945, Price-Patterson, ISBN 1-896881-15-7.

- ↑ Ewa Kurek (2 August 2012). Polish-Jewish Relations 1939–1945: Beyond the Limits of Solidarity. iUniverse. p. 305. ISBN 978-1-4759-3832-6.

- ↑ Richard Z. Chesnoff, "The Other Schindlers: Steven Spielberg's epic film focuses on only one of many unsung heroes" (archive), U.S. News and World Report, 13 March 1994.

- 1 2 3 4 "Irena Sendler". jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- 1 2 Monika Scislowska, Associated Press Writer (May 12, 2008). "Polish Holocaust hero dies at age 98". USA Today. Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ↑ "L.S.I.C.". Archived from the original on 28 July 2009. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ↑ Mordecai Paldiel "Churches and the Holocaust: unholy teaching, good samaritans, and reconciliation" pp. 209–10, KTAV Publishing House, Inc., 2006, ISBN 978-0-88125-908-7

- 1 2 3 Atwood, Kathryn (2011). Women Heroes of World War II. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. p. 46. ISBN 9781556529610.

- 1 2 Hevesi, Dennis (13 May 2008). "Irena Sendler, Lifeline to Young Jews, Is Dead at 98". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "THE 614th Commandment Society". Aktualności. Irena Sendler ambasadorem Polski – cz.2. The614thcs.com. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Sendler Irena – WIEM, darmowa encyklopedia" (in Polish). PortalWiedzy.onet.pl. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Irena Stanisława Sendler (1910–2008) – dzieje.pl" (in Polish). Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "Irena Sendler, who saved 2,500 Jews from Holocaust, dies at 98". Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "To była matka całego świata – córka Ireny Sendler opowiedziała nam o swojej mamie". Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ Louette Harding (1 August 2008). "Irena Sendler: a Holocaust heroine". The Daily Mail online, Associated Newspapers. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ David M. Dastych (May 16, 2008). "Irena Sendler: Compassion and Courage". Editorial. CanadaFreePress.com. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- 1 2 Zawadzka, Maria. "TREES OF IRENA SENDLER AND JAN KARSKI IN THE GARDEN OF THE RIGHTEOUS". Polish Righteous. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "2013 Irena Sendler". Adas Israel Congregation. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Smuggling Children out of the Ghetto. Irena Sendler. Poland". The Righteous Among the Nations. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority. 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ↑ "Irena Sendler". Jewish Virtual Library. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE). Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ .P. 1996 nr 58 poz. 538, citation: "za pełną poświęcenia i ofiarności postawę w niesienui pomocy dzieciom żydowskim oraz za działalnośċ spoleczną i zawodową" (Polish)

- ↑ "Krzyz Komandorski Orderu Odrodzenia Polski..." (in Polish). Retrieved 2015-04-27.

- ↑ M.P. 2002 nr 3 poz. 55, citation: "w uznanui wybitnych zasług w nieseniu pomocy potrzebującym" (Polish)

- ↑ "About the Project – Life in a Jar". Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "Jar Of Life – Teens discover heroic deeds of another 'Schindler'" July 01, 2002, Lubbock Avalanche – Journal (retrieved May 8, 2015)

- ↑ The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler at CBS.com Archived 21 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Hallmark Corporate Information – Error". hallmark.com.

- ↑ Richard Maurer (ram-30) (19 April 2009). "The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler (TV Movie 2009)". IMDb.

- ↑ "List Papieża do Ireny Sendler [Letter of the Pope to Irena Sendler]". wyborcza.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ Scott T. Allison; George R. Goethals (2011). Heroes: What They Do and Why We Need Them. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-973974-5.

- ↑ M.P. 2004 nr 13 poz. 212, citation: "za bohaterstwo i niezwykłą odwagę, za szczególne zasługi w ratowaniu życia ludzkiego" ("for heroism and extraordinary courage, for outstanding merits in saving human lives") (Polish)

- ↑ Warszawa, Grupa. "The Association of "Children of the Holocaust" in Poland". www.dzieciholocaustu.org.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2015-04-27.

- ↑ "Opis konkursu". Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- 1 2 "Polscy Sprawiedliwi – Przywracanie Pamięci". www.sprawiedliwi.org.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2015-04-27.

- ↑ Mellgren, Doug. "Oprah and Gore among 181 peace prize nominees". The Guardian UK. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Irena Sendler – polska bohaterka nominowana do Nagrody Nobla – PoloniaInfo". www.poloniainfo.se. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ↑ "IFSW supported nomination of Irena Sendler for Nobel Peace Prize". International Federation of Social Workers.

- ↑ Wyszyński, Kuba. "Irena Sendler nie żyje". www.jewish.org.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2015-04-27.

- ↑ "Congressional Record – 110th Congress (2007–2008) – THOMAS (Library of Congress)". thomas.loc.gov. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "IRENA SENDLEROWA Kawalerem Orderun Uśmiechu". orderusmiechu.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2015-04-27.

- ↑ "Nagroda im. Ireny Sendlerowej". nagrodairenysendlerowej.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2015-04-27.

- ↑ Smolen, Courtney. "Executive Director of NJ Commission on Holocaust Education to Bestow Honorary Award to CSE Professor, April 19". NJ.com. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Irena Sendler awarded the Audrey Hepburn Humanitarian Award". www.audrey1.org. Retrieved 2015-04-27.

- ↑ "PBS National Premiere of IRENA SENDLER In the Name of Their Mothers on May 1st, National Holocaust Remembrance Day". KQED's Pressroom.

- ↑ "SF-Krakow Sister Cities Association – Irena Sendler Documentary Film Wins 2012 Gracie Award". www.sfkrakow.org. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "Aleja Ireny Sendlerowej, Honorowej Obywatelki m.st. Warszawy". www.radawarszawy.um.warszawa.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "Odsłonięto tablicę upamiętniającą Irenę Sendlerową". www.http://wiadomosci.wp.pl/ (in Polish). Retrieved 24 June 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - 1 2 "About the Project". Life in a Jar: The Irena Sendler Project. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ Mieszkowska, Anna. "Prawdziwa historia Ireny Sendlerowej". Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ↑ "Three Twice-told stories". Toronto Star, November 12, 2016, page E22.

References

- Yitta Halberstam & Judith Leventhal, Small Miracles of the Holocaust, The Lyons Press; 1st edition (13 August 2008), ISBN 978-1-59921-407-8

- Richard Lukas, Forgotten Survivors: Polish Christians Remember the Nazi Occupation ISBN 978-0-7006-1350-2

- Anna Mieszkowska, IRENA SENDLER Mother of the Holocaust Children Publisher: Praeger; Tra edition (18 November 2010) Language: English ISBN 978-0-313-38593-3

- Mordecai Paldiel, The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust, Ktav Publishing House (January 1993), ISBN 9780881253764

- Irene Tomaszewski & Tecia Werblowski, Zegota: The Council to Aid Jews in Occupied Poland 1942–1945, Price-Patterson, ISBN 1-896881-15-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Irena Sendlerowa. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Irena Sendler |

- Irena Sendler: In the Name of Their Mothers (PBS documentary, first aired May 2011)

- Irena Sendler – Righteous Among the Nations – Yad Vashem

- Irena Sendlerowa on History's Heroes – Illustrated story and timeline.

- Life in a Jar: The Irena Sendler Project

- Irena Sendler at Find a Grave

- Snopes discussion of an email regarding the Nobel Prize