Invicta International Airlines Flight 435

|

Invicta International Airlines Vickers 952 Vanguard G-AXOP, the one involved in the crash. | |

| Occurrence summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | 10 April 1973 |

| Summary | Controlled flight into terrain |

| Site | 300 m south of the Herrenmatt hamlet, Hochwald, Switzerland |

| Passengers | 139 |

| Crew | 6 |

| Fatalities | 108 |

| Injuries (non-fatal) | 36 |

| Survivors | 37 |

| Aircraft type | Vickers Vanguard |

| Operator | Invicta International Airlines |

| Registration | G-AXOP |

| Flight origin | Bristol Lulsgate Airport |

| Destination | Basle-Mulhouse Airport |

Invicta International Airways Flight 435 (IM435) was a Vickers Vanguard 952, flying from Bristol Lulsgate to Basel-Mulhouse, that ploughed into a snowy, forested hillside near Hochwald, Switzerland. It somersaulted and broke up, killing 108, with 37 survivors. To date, this is the deadliest accident involving a Vickers Vanguard and the deadliest aviation accident to occur on Swiss soil.[1] Many of the 139 passengers on the charter flight were women, members of the Axbridge Ladies Guild, from the Somerset towns and villages of Axbridge,[2] Cheddar, Winscombe and Congresbury.[3][4][5] The accident left 55 children motherless.[2]

Pilot Anthony Dorman became disoriented, misidentifying two radio beacons and missing another.[2] When co-pilot Ivor Terry took over, his final approach was based on the wrong beacon and the aircraft crashed into the hillside.[2] Dorman had previously been suspended from the Royal Canadian Air Force for lack of ability, and had failed his United Kingdom instrument flying rating eight times.[6] As a result of the crash tougher regulations were introduced in the UK.

Despite the conclusions of the official Swiss report, one commentator, ex-KLM pilot Jan Bartelski, has argued that the pilots may not have been entirely to blame and that there is a possibility that they were led off course by "ghost" beacon transmissions caused by electric power lines.[7]

Flight

The aircraft was a Vickers Vanguard 952, registered as G-AXOP, and was chartered by a tour company based in Britain. Flight 435 took off from Bristol (Lulsgate) Airport, Lulsgate Bottom, North Somerset, United Kingdom for EuroAirport Basel Mulhouse Freiburg International Airport in Basel, Saint-Louis, France. The airport was located just miles from the border of Switzerland and Germany, located in mountainous terrain. The aircraft had taken off initially from London's Luton International Airport, and had a transit in Bristol.[5]

A total of 139 passengers and crew were taken on board in Bristol. At 07:19 UTC, Flight 435 took off from Bristol. Captain Anthony Dorman flew the plane, while his co-pilot Captain Ivor Terry was handling communication. The flight was uneventful until its first approach. It was daylight at the time, so visual references could be easily obtained by the crew. However, a heavy snowstorm was reported in Basel, this reducing the visibility there.[5]

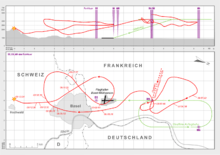

While approaching Basel, Flight 435 passed two approach beacons in Basel, named as beacon MN and BN. However, the aircraft overshot. Captain Dorman then initiated a go-around. The crew then tried to pass both beacons again.[5]

At 09:08 UTC, Basel Control Tower received a telephone call from a meteorologist and a former aircraft commander that barely two minutes before Flight 435 had flown above the Binningen Observatory (approximately eight kilometers southeast from the airport) at around fifty meters above the ground and heading south; he urged the crews of Flight 435 to climb immediately. During the approach, several passengers briefly saw several houses on the ground. While the meteorologist was still on the phone, the crew reported that they had passed the first beacon, named as MN. They were instructed to pass the second beacon, BN.[5]

At 09:11 UTC, Zurich Area Control Centre asked Basel Control whether they had an aircraft which was flying outbound towards Hochwald, as they had observed an unidentified echo on their radar screen, a few miles from Basel. Basel Control Tower denied this, but when the controller checked his radar screen he saw an unidentified echo moving to the south, a few miles from the airport. Flight 435 then reported that it had passed beacon BN, and was given a landing clearance.[5]

After finishing its telephone call with Zurich, Basel controller asked if Flight 435 was sure that they had passed beacon BN. Flight 435 replied that they had a "spurious indication" and that they were in short pause on the ILS. The crew then confirmed that beacon BN was on their glide path and localizer, while the controller stated that he could not see them on his radar screen. The controller then informed the crew; "I think you are not on the short pause, you are on the south of the airfield." Flight 435 didn't respond. After this message, all calls to Flight 435 went unanswered.[5]

At 09:13 UTC, the aircraft brushed the wooded area of a range of hills in Jura and crashed in the hamlet of Herrenmatt, in the parish of Hochwald. The aircraft somersaulted and exploded, several parts of it catching fire. 108 passengers and crew were killed, while 37 others survived the crash; 36 of these were injured, while one air hostess was unhurt.[5]

On hitting the ground, the aircraft snapped into several sections. While the front parts were "destroyed into bits", a section of the tail was left substantially intact. This was the area where most survivors were found. Everyone seated in the front part of the aircraft was killed.[5]

In the aftermath of the crash, survivors began helping each other. It was snowing at the time, and hypothermia could easily occur. While pulling dead bodies from the wreckage, they began chanting hymns to keep their spirits high. Shortly afterwards, a boy from a nearby farm found the survivors, and led them to his house, where his family sheltered and took care of them while waiting for rescue services to arrive.

Passengers and crew

Most of the passengers and crew were British citizens, and many of them were a group of women from Axbridge in Somerset, United Kingdom.[5]

The pilot who handled the aircraft was Captain Anthony Noel Dorman, a Canadian citizen, born in 1938, with a valid British pilot's license for a Vickers Vanguard, Britten-Norman BN2 Islander, Douglas DC-2 and Douglas DC-3. Captain Dorman had begun his flight training with the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1963, but it was soon discontinued owing to his insufficient aptitude for flying. Following his discharge from the Air Force, he obtained a Canadian private pilot's license. He later obtained a commercial pilot's license and finally a senior commercial pilot's license, and then a Nigerian pilot's license.[5]

Captain Dorman had tried at least nine times in the United Kingdom to obtain an instrument rating license for light aircraft and successfully obtained it in January 1971. He had failed the test several times owing to inadequate flying hours and lack of knowledge. He later passed a test for the DC-2, DC-3, and Vickers Vanguard. Also in January 1971, he obtained a British airline pilot's license, and later joined Invicta International Airlines. In the first year he was employed by Invicta as a co-pilot on a Douglas DC-4, and later on a Vickers Vanguard. In October 1972, he was promoted to Captain.[5]

Captain Dorman had a total flying experience of 1,205 hours, with approximately 1,088 hours on the Vickers Vanguard. He had previous experience of Basel, having made 33 previous landings there, nine of which were instrument approach. He had flown seventeen times before with the co-pilot Captain Terry.[5]

The co-pilot, Captain Ivor William Francis Terry, was born in 1926. He was a British citizen and held a British airline pilot's license. He had begun his flight training with the Royal Air Force in October 1944 and had been a military pilot since 1947, with flight duties including Lancaster, Shackleton, Varsity and Valleta.[5]

Captain Terry was promoted to Captain in October 1968 on a DC-4, and obtained a Vickers Vanguard license in 1971. He had a total flying experience of 9,172 hours, of which 3,144 were on the type. He had landed 61 times in Basel, with fourteen of them on instrument approach.[5]

Investigation

The aircraft was only equipped with a Flight Data Recorder. At the time of the accident, the aviation regulations in the United Kingdom didn't require the presence of a Cockpit Voice Recorder in every aircraft.[5]

Meteorological agencies reported that snowstorms were present during Flight 435's approach, which would limit visibility. As Basel was located in a mountainous area, this limited visibility would be dangerous as the aircraft was not equipped with a Ground Proximity Warning System (GPWS).[5]

Based on Air Traffic Control recording, the Basel Air Controller stated that Flight 435 was not on the selected beacon, while the crew of the flight stated that they were on the beacon. This could indicate a faulty signal or faulty navigational equipment. If the fault was in the navigation system, this could explain why the plane went astray from its selected path.[5]

Investigation on the Basel's ADF revealed that the ADF had poorly soldered joints in its loop servo amplifier in system No 1. These poorly soldered joints might have led to intermittent interruptions of the individual electrical connections in the amplifier. This fault was not noticed by the crew. The investigation could not determine the cause of the fault.[5]

The fault in the ADF system made it impossible to be used as an approach aid. The VOR flag alarm was set too high and the glide-slope deflection sensitivity indication was set 50% more than its usual operational setting. It didn't prevent the system, but was rather "exacting for the pilots". The faulty settings of the glide-slope alarm circuit prevented the flag appearing until the two signals were unusable or not received. If the faulty unit received an "unsatisfactory signal", the pointer could move to the mid-position. The pilot on the left seat could not notice this failure. This is dangerous. If the pointer moved to the mid-position, the crew would have thought that they were on the correct glide path. Investigators then questioned the airworthiness of the aircraft due to these faults.[5]

Investigators became concerned that there might be more faults in the aircraft. The investigation further revealed that there were some serious malfunctions in the aircraft's equipment. The botched solder work found in the equipment was carried out partly during its production and partly during the repair.[5]

Both flight crews, Captain Dorman and Captain Terry, held a Captain rating. However, Captain Terry was far senior to Captain Dorman. Captain Terry handled the first route segment, from Luton to Bristol, while Captain Dorman handled the Bristol to Basel route. Experience has shown that this kind of crew combination has undesirable consequences. The pilot in the right seat, Captain Terry, has insufficient co-pilot experience. Because he was a senior Captain, he acted and thought like a Captain rather than a co-pilot. The aircraft commander, Captain Dorman, was probably irritated by the presence of a pilot in the same rank, causing a dangerous situation.[5]

The inclement weather condition, and the fact that the modulation of the two beacons didn't comply with ICAO requirements, caused every crew on every flight approaching Basel at the time to have some difficulties. The ADF indication was usable, but it was not reliable enough. Because it was not reliable, it was essential to monitor the aircraft's position by additional static-free navigational aids, or by radar from the ground.[5]

Summary

The investigators then summarized the events that happened on Flight 435, as based on the final report:

"The flight path during the descent from HR to BN was normal; it then becomes highly erratic with regard to navigation and maintenance of height, deviating considerably from the prescribed flight path and prescribed height.

During the second procedure turn before the first final approach, a navigational error was obviously made, as the aircraft headed straight for BN again instead of beacon MN. One cannot say whether this was due to the fact that the two beacons were not set on the ADFs in the normal sequence (ADF 1 to BN, ADF 2 to MN; the opposite settings were found in the wreckage).

Following the second procedure turn, a continual descent begins from a height of approximately 3,200 ft, as they had a definite glide path indication. This could not, however, have come from the ILS glide path transmitter, as the flight path led over the glide path station with its many weak and steep secondary glide path beams. The flight director system could offer an explanation for the regular rates of descent. At approximately 3,200 ft over N a spurious glide path was crossed during the second procedure turn. Now if on the basis of this indication, which might have also coincided with a localizer indication, the flight director was set to the approach mode in order to follow both pointers on this, the subsequent approach might be explained, but only if the two pilots neglected to keep the normal, continuous, mutual check on the basic navigational instruments and the marker control. The artificial horizon pitch bar which is not integrated with the ILS glide path signals required an average rate of descent of approximately 500 ft/min to maintain a 2.5° glide path without wind correction. In this instrumentation, the ILS glide path indication takes the form of a small triangle in the artificial horizon.

The reason for the poor tracking of the ILS localizer during the first approach attempt can be explained by the defect found on the Captain's ILS equipment. The flag current which was set too high is not of significance here, as the aircraft never flew in an area where this localizer flag would normally have to respond. There should have been a localizer indication the whole hand. On the other hand, it was extremely disturbing that the deflection sensitivity of the localizer had been set more than 50% too high. Because the localizer indication and therefore the IFS steering pointer too were so "jittery", they could hardly be followed anymore. In addition, it was easy to miss crossing the localizer, as this only lasted 3–4 seconds after the second procedure turn, which was completely unsuccessful, instead of the usual 10 seconds. The difficulties in intercepting and following the localizer up to the first overshoot, which is the latest time that a change of pilot and therefore also a change of the primarily used blind flying instruments may be assumed, become evident if one compares the flight path of the first section with that of the second.

As an unrectified, at least temporary, defect in the captain's ILS equipment had also led to a final approach to the left of the approach path the day before, the approach path on the first approach attempt, which was obviously too far to the left, possibly indicated that this technical defect had recurred.

Despite the prevailing unfavourable conditions with regard to the weather, instability of the ADFs and oversensitivity of the ILS localizer indication on the instruments of the pilot flying the aircraft, the first approach attempt following the confusion of the beacons need not necessarily have led to the dangerous flight path established. These conditions, some of which the crew was aware of, could be expected to have prompted them to make a careful, repeatedly verified approach, with continual mutual monitoring, in the course of which any discrepancies would soon be discovered and the ATC help requested in case of doubt. However, nothing of the kind occurred.

The maintenance of height was erratic and should have been reported to the ATC. The inference of the values recorded by the Flight Data Recorder is that the considerable deviations in height did not result from turbulence or vertical gusts.

The markers were not used to identify the beacons and the correct glide path altitude.

The crew's conduct following discontinuation of the first approach attempt is inexplicable. Although it must be assumed on the basis of the witness statements and the pilot of the flight path that the crew realised what a dangerous manoeuvre they had carried out - instead of the unbuilt-up and flat outlying ground of the aerodrome a densely populated and hilly area came into view even before the normal ILS approach minimum was reached - no fundamentally new safety measures were taken. Apparently only the certainly expedient change of pilot and, consequently, instruments took place, which admittedly resulted in accurately flown turns and courses but still did not rely on the marker beacon emissions which were essential for an ILS in view of the atmospheric disturbances. Instead of requesting the help of Air Traffic Control, who were intermittently occupied with other aircraft, or diverting to an alternate aerodrome, they may well have attempted, according to a possible interpretation of the tape recording, to make the second approach using only localizer and glide path and time and course navigation, which could not succeed in view of the "bungled" situation. The fact that the second approach was initiated with position report MN in the immediate vicinity of the BS beacon could be looked upon as a further confusion of navigational aids.

It is not possible to say what happened in the cockpit and how the various mistakes and wrong decisions and the shortcomings in the pilots' monitoring of each other came about, as no cockpit voice recorder was carried, which would doubtless have been able to provide many clues, thereby making it easier to recommend what action should be taken to prevent similar accidents. There are no clues or explanations as to what had distracted the crew from their work to such an extent or had hindered their monitoring of each other."

See also

- Alitalia Flight 404, a plane crash near Zurich where the pilot lost orientation owing to faulty beacon receiver.

- Pan Am Flight 812

References

- ↑ "ASN Aircraft accident Vickers 952 Vanguard G-AXOP Basel/Mulhouse Airport (BSL)". Aviation Safety Network (ASN). Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Faith, Nicholas (1996). Black Box. Boxtree. p. 166. ISBN 0-7522-1084-X.

- ↑ "Fatal fatigue". Time. 23 April 1973.

- ↑ Hansard 11 April 1973

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 "Report No: 11/1975. Vickers Vanguard 952, G-AXOP. Report on the accident at Hochwald/Solothurn, Switzerland, on 10 April 1973". Air Accidents Investigation Branch. 1975.

- ↑ Forman, Patrick (1990). Flying into danger: the hidden facts about air safety. Heinemann. pp. 5, 111. ISBN 978-0-434-26864-1.

- ↑ Bartelski, Jan (2001) Disasters in the Air. Airlife Publishing Ltd. pp 208–229 ISBN 1-84037-204-4

External links

- Final report (Archive) – Swiss Federal Department of Transport and Power – Translated by the Department of Trade Accidents Investigation Branch. 30 May 1975.

Coordinates: 47°27′15″N 7°37′24″E / 47.45417°N 7.62333°E