Inverse agonist

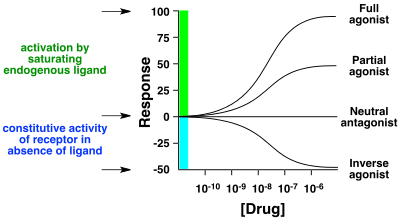

In the field of pharmacology, an inverse agonist is an agent that binds to the same receptor as an agonist but induces a pharmacological response opposite to that agonist. A neutral antagonist has no activity in the absence of an agonist or inverse agonist but can block the activity of either.[1] Inverse agonists have opposite actions to those of agonists but the effects of both of these can be blocked by antagonists.[2]

A prerequisite for an inverse agonist response is that the receptor must have a constitutive (also known as intrinsic or basal) level activity in the absence of any ligand. An agonist increases the activity of a receptor above its basal level, whereas an inverse agonist decreases the activity below the basal level.

The efficacy of a full agonist is by definition 100%, a neutral antagonist has 0% efficacy, and an inverse agonist has < 0% (i.e., negative) efficacy.

Examples

An example of a receptor that possesses basal activity and for which inverse agonists have been identified is the GABAA receptor. Agonists for the GABAA receptor (such as benzodiazepines) create a sedative effect, whereas inverse agonists have anxiogenic effects (for example, Ro15-4513) or even convulsive effects (certain beta-carbolines).[3][4]

Two known endogenous inverse agonists are the Agouti-related peptide (AgRP) and its associated peptide Agouti signalling peptide (ASIP). Both appear naturally in humans, and each binds melanocortin receptors 4 and 1 (Mc4R and Mc1R), respectively, with nanomolar affinities.[5]

The opioid antagonists naloxone and naltrexone are also partial inverse agonists at mu opioid receptors.

See also

References

- ↑ Kenakin T (April 2004). "Principles: receptor theory in pharmacology". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 25 (4): 186–92. PMID 15063082. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2004.02.012.

- ↑ Inverse agonists - What do they mean for psychiatry? doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.11.013

- ↑ Mehta AK, Ticku MK (August 1988). "Ethanol potentiation of GABAergic transmission in cultured spinal cord neurons involves gamma-aminobutyric acidA-gated chloride channels". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 246 (2): 558–64. PMID 2457076.

- ↑ Sieghart W (January 1994). "Pharmacology of benzodiazepine receptors: an update". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 19 (1): 24–9. PMC 1188559

. PMID 8148363.

. PMID 8148363. - ↑ Ollmann MM, Lamoreux ML, Wilson BD, Barsh GS (February 1998). "Interaction of Agouti protein with the melanocortin 1 receptor in vitro and in vivo". Genes & Development. 12 (3): 316–30. PMC 316484

. PMID 9450927. doi:10.1101/gad.12.3.316.

. PMID 9450927. doi:10.1101/gad.12.3.316.

Further reading

- Khilnani G, Khilnani AK (September 2011). "Inverse agonism and its therapeutic significance". Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 43 (5): 492–501. PMC 3195115

. PMID 22021988. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.84947.

. PMID 22021988. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.84947.

External links

- Jeffries WB (1999-02-17). "Inverse Agonists for Medical Students". Office of Medical Education - Courses - IDC 105 Principles of Pharmacology. Creighton University School of Medicine - Department of Pharmacology. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- Inverse Agonists: An Illustrated Tutorial Panesar K, Guzman F. Pharmacology Corner. 2012