Introduction to evolution

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

|

History of evolutionary theory |

|

Fields and applications

|

|

Evolution is the process of change in all forms of life over generations, and evolutionary biology is the study of how evolution occurs. Biological populations evolve through genetic changes that correspond to changes in the organisms' observable traits. Genetic changes include mutations, which are caused by damage or replication errors in an organism's DNA. As the genetic variation of a population drifts randomly over generations, natural selection gradually leads traits to become more or less common based on the relative reproductive success of organisms with those traits.

The age of the Earth is about 4.54 billion years.[1][2][3] The earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates at least from 3.5 billion years ago,[4][5][6] during the Eoarchean Era after a geological crust started to solidify following the earlier molten Hadean Eon. There are microbial mat fossils found in 3.48 billion-year-old sandstone discovered in Western Australia.[7][8][9] Other early physical evidences of life include graphite, a biogenic substance, in 3.7 billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks discovered in western Greenland[10] and, in 2015, "remains of biotic life" found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks in Western Australia.[11][12] According to one of the researchers, "If life arose relatively quickly on Earth ... then it could be common in the universe."[11] More than 99 percent of all species, amounting to over five billion species,[13] that ever lived on Earth are estimated to be extinct.[14][15] Estimates on the number of Earth's current species range from 10 million to 14 million,[16] of which about 1.2 million have been documented and over 86 percent have not yet been described.[17] More recently, in May 2016, scientists reported that 1 trillion species are estimated to be on Earth currently with only one-thousandth of one percent described.[18]

Evolution does not attempt to explain the origin of life (covered instead by abiogenesis), but it does explain how the extremely simple early lifeforms evolved into the complex ecosystem that we see today.[19] Based on the similarities between all present-day organisms, all life on Earth originated through common descent from a last universal ancestor from which all known species have diverged through the process of evolution.[20] All individuals have hereditary material in the form of genes that are received from their parents, then passed on to any offspring. Among offspring there are variations of genes due to the introduction of new genes via random changes called mutations or via reshuffling of existing genes during sexual reproduction.[21][22] The offspring differs from the parent in minor random ways. If those differences are helpful, the offspring is more likely to survive and reproduce. This means that more offspring in the next generation will have that helpful difference and individuals will not have equal chances of reproductive success. In this way, traits that result in organisms being better adapted to their living conditions become more common in descendant populations.[21][22] These differences accumulate resulting in changes within the population. This process is responsible for the many diverse life forms in the world.

The forces of evolution are most evident when populations become isolated, either through geographic distance or by other mechanisms that prevent genetic exchange. Over time, isolated populations can branch off into new species.[23][24]

The majority of genetic mutations neither assist, change the appearance of, nor bring harm to individuals. Through the process of genetic drift, these mutated genes are neutrally sorted among populations and survive across generations by chance alone. In contrast to genetic drift, natural selection is not a random process because it acts on traits that are necessary for survival and reproduction.[25] Natural selection and random genetic drift are constant and dynamic parts of life and over time this has shaped the branching structure in the tree of life.[26]

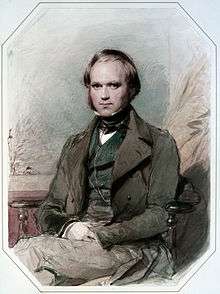

The modern understanding of evolution began with the 1859 publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species. In addition, Gregor Mendel's work with plants helped to explain the hereditary patterns of genetics.[27] Fossil discoveries in paleontology, advances in population genetics and a global network of scientific research have provided further details into the mechanisms of evolution. Scientists now have a good understanding of the origin of new species (speciation) and have observed the speciation process in the laboratory and in the wild. Evolution is the principal scientific theory that biologists use to understand life and is used in many disciplines, including medicine, psychology, conservation biology, anthropology, forensics, agriculture and other social-cultural applications.

Simple overview

The main ideas of evolution may be summarized as follows:

- Life forms reproduce and therefore have a tendency to become more numerous.

- Factors such as predation and competition work against the survival of individuals.

- Each offspring differs from their parent(s) in minor, random ways.

- If these differences are beneficial, the offspring is more likely to survive and reproduce.

- This makes it likely that more offspring in the next generation will have beneficial differences and fewer will have detrimental differences.

- These differences accumulate over generations, resulting in changes within the population.

- Over time, populations can split or branch off into new species.

- These processes, collectively known as evolution, are responsible for the many diverse life forms seen in the world.

Natural selection

In the 19th century, natural history collections and museums were a popular pastime. The European expansion and naval expeditions employed naturalists and curators of grand museums showcasing preserved and live specimens of the varieties of life. Charles Darwin was an English graduate who was educated and trained in the disciplines of natural history science. Such natural historians would collect, catalogue, describe and study the vast collections of specimens stored and managed by curators at these museums. Darwin served as a ship's naturalist on board the HMS Beagle, assigned to a five-year research expedition around the world. During his voyage, he observed and collected an abundance of organisms, being very interested in the diverse forms of life along the coasts of South America and the neighboring Galápagos Islands.[28][29]

Darwin gained extensive experience as he collected and studied the natural history of life forms from distant places. Through his studies, he formulated the idea that each species had developed from ancestors with similar features. In 1838, he described how a process he called natural selection would make this happen.[30]

The size of a population depends on how much and how many resources are able to support it. For the population to remain the same size year after year, there must be an equilibrium, or balance between the population size and available resources. Since organisms produce more offspring than their environment can support, not all individuals can survive out of each generation. There must be a competitive struggle for resources that aid in survival. As a result, Darwin realised that it was not chance alone that determined survival. Instead, survival of an organism depends on the differences of each individual organism, or "traits," that aid or hinder survival and reproduction. Well-adapted individuals are likely to leave more offspring than their less well-adapted competitors. Traits that hinder survival and reproduction would disappear over generations. Traits that help an organism survive and reproduce would accumulate over generations. Darwin realised that the unequal ability of individuals to survive and reproduce could cause gradual changes in the population and used the term natural selection to describe this process.[31][32]

Observations of variations in animals and plants formed the basis of the theory of natural selection. For example, Darwin observed that orchids and insects have a close relationship that allows the pollination of the plants. He noted that orchids have a variety of structures that attract insects, so that pollen from the flowers gets stuck to the insects' bodies. In this way, insects transport the pollen from a male to a female orchid. In spite of the elaborate appearance of orchids, these specialised parts are made from the same basic structures that make up other flowers. In his book, Fertilisation of Orchids (1862), Darwin proposed that the orchid flowers were adapted from pre-existing parts, through natural selection.[33]

Darwin was still researching and experimenting with his ideas on natural selection when he received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace describing a theory very similar to his own. This led to an immediate joint publication of both theories. Both Wallace and Darwin saw the history of life like a family tree, with each fork in the tree’s limbs being a common ancestor. The tips of the limbs represented modern species and the branches represented the common ancestors that are shared amongst many different species. To explain these relationships, Darwin said that all living things were related, and this meant that all life must be descended from a few forms, or even from a single common ancestor. He called this process descent with modification.[32]

Darwin published his theory of evolution by natural selection in On the Origin of Species in 1859. His theory means that all life, including humanity, is a product of continuing natural processes. The implication that all life on Earth has a common ancestor has met with objections from some religious groups. Their objections are in contrast to the level of support for the theory by more than 99 percent of those within the scientific community today.[34]

Natural selection is commonly equated with survival of the fittest, but this expression originated in Herbert Spencer's Principles of Biology in 1864, five years after Charles Darwin published his original works. Survival of the fittest describes the process of natural selection incorrectly, because natural selection is not only about survival and it is not always the fittest that survives.[35]

Source of variation

Orange labels: known ice ages.

Also see: Human timeline and Nature timeline

Darwin’s theory of natural selection laid the groundwork for modern evolutionary theory, and his experiments and observations showed that the organisms in populations varied from each other, that some of these variations were inherited, and that these differences could be acted on by natural selection. However, he could not explain the source of these variations. Like many of his predecessors, Darwin mistakenly thought that heritable traits were a product of use and disuse, and that features acquired during an organism's lifetime could be passed on to its offspring. He looked for examples, such as large ground feeding birds getting stronger legs through exercise, and weaker wings from not flying until, like the ostrich, they could not fly at all.[36] This misunderstanding was called the inheritance of acquired characters and was part of the theory of transmutation of species put forward in 1809 by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. In the late 19th century this theory became known as Lamarckism. Darwin produced an unsuccessful theory he called pangenesis to try to explain how acquired characteristics could be inherited. In the 1880s August Weismann's experiments indicated that changes from use and disuse could not be inherited, and Lamarckism gradually fell from favor.[37]

The missing information needed to help explain how new features could pass from a parent to its offspring was provided by the pioneering genetics work of Gregor Mendel. Mendel’s experiments with several generations of pea plants demonstrated that inheritance works by separating and reshuffling hereditary information during the formation of sex cells and recombining that information during fertilisation. This is like mixing different hands of playing cards, with an organism getting a random mix of half of the cards from one parent, and half of the cards from the other. Mendel called the information factors; however, they later became known as genes. Genes are the basic units of heredity in living organisms. They contain the information that directs the physical development and behavior of organisms.

Genes are made of DNA. DNA is a long molecule made up of individual molecules called nucleotides. Genetic information is encoded in the sequence of nucleotides, that make up the DNA, just as the sequence of the letters in words carries information on a page. The genes are like short instructions built up of the "letters" of the DNA alphabet. Put together, the entire set of these genes gives enough information to serve as an "instruction manual" of how to build and run an organism. The instructions spelled out by this DNA alphabet can be changed, however, by mutations, and this may alter the instructions carried within the genes. Within the cell, the genes are carried in chromosomes, which are packages for carrying the DNA. It is the reshuffling of the chromosomes that results in unique combinations of genes in offspring. Since genes interact with one another during the development of an organism, novel combinations of genes produced by sexual reproduction can increase the genetic variability of the population even without new mutations.[38] The genetic variability of a population can also increase when members of that population interbreed with individuals from a different population causing gene flow between the populations. This can introduce genes into a population that were not present before.[39]

Evolution is not a random process. Although mutations in DNA are random, natural selection is not a process of chance: the environment determines the probability of reproductive success. Evolution is an inevitable result of imperfectly copying, self-replicating organisms reproducing over billions of years under the selective pressure of the environment. The outcome of evolution is not a perfectly designed organism. The end products of natural selection are organisms that are adapted to their present environments. Natural selection does not involve progress towards an ultimate goal. Evolution does not strive for more advanced, more intelligent, or more sophisticated life forms.[40] For example, fleas (wingless parasites) are descended from a winged, ancestral scorpionfly, and snakes are lizards that no longer require limbs—although pythons still grow tiny structures that are the remains of their ancestor's hind legs.[41][42] Organisms are merely the outcome of variations that succeed or fail, dependent upon the environmental conditions at the time.

Rapid environmental changes typically cause extinctions.[43] Of all species that have existed on Earth, 99.9 percent are now extinct.[44] Since life began on Earth, five major mass extinctions have led to large and sudden drops in the variety of species. The most recent, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, occurred 66 million years ago.[45]

Genetic drift

Genetic drift is a cause of allelic frequency change within populations of a species. Alleles are different variations of specific genes. They determine things like hair color, skin tone, eye color and blood type; in other words, all the genetic traits that vary between individuals. Genetic drift does not introduce new alleles to a population, but it can reduce variation within a population by removing an allele from the gene pool. Genetic drift is caused by random sampling of alleles. A truly random sample is a sample in which no outside forces affect what is selected. It is like pulling marbles of the same size and weight but of different colors from a brown paper bag. In any offspring, the alleles present are samples of the previous generations alleles, and chance plays a role in whether an individual survives to reproduce and to pass a sample of their generation onward to the next. The allelic frequency of a population is the ratio of the copies of one specific allele that share the same form compared to the number of all forms of the allele present in the population.[46]

Genetic drift affects smaller populations more than it affects larger populations.[47]

Hardy–Weinberg principle

The Hardy–Weinberg principle states that a large population in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium will have no change in the frequency of alleles as generations pass.[48] It is impossible for a population of any considerable size to reach this equilibrium because of the five requirements that must be met. A population must be infinite in size. There must be a zero percent mutation rate between generations, because mutations can alter existing alleles or create new ones. There can be no immigration or emigration in the population, because individuals arriving and leaving directly change allelic frequencies. There can be no selective pressures of any kind on the population, meaning that no individual is more likely than any other to survive and reproduce. Finally, mating must be totally random, with all males (or females in some cases) being equally desirable mates. This ensures a true random mixing of alleles.[49]

A population that is in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium is analogous to a deck of cards; no matter how many times the deck is shuffled, no new cards are added and no old ones are taken away. Cards in the deck represent alleles in a population’s gene pool.

Population bottleneck

A population bottleneck occurs when the population of a species is reduced drastically over a short period of time due to external forces.[50] In a true population bottleneck, the reduction does not favor any combination of alleles; it is totally random chance which individuals survive. A bottleneck can reduce or eliminate genetic variation from a population. Further drift events after the bottleneck event can also reduce the population's genetic diversity. The lack of diversity created can make the population at risk to other selective pressures.[51]

A common example of a population bottleneck is the Northern elephant seal. Due to excessive hunting throughout the 19th century, the population of the northern elephant seal was reduced to 30 individuals or less. They have made a full recovery, with the total number of individuals at around 100,000 and growing. The effects of the bottleneck are visible, however. The seals are more likely to have serious problems with disease or genetic disorders, because there is almost no diversity in the population.[52]

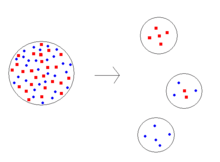

Founder effect

The founder effect occurs when a small group from one population splits off and forms a new population, often through geographic isolation. This new population's allelic frequency is probably different from the original population's, and will change how common certain alleles are in the populations. The founders of the population will determine the genetic makeup, and potentially the survival, of the new population for generations.[49]

One example of the founder effect is found in the Amish migration to Pennsylvania in 1744. Two of the founders of the colony in Pennsylvania carried the recessive allele for Ellis–van Creveld syndrome. Because the Amish tend to be religious isolates, they interbreed, and through generations of this practice the frequency of Ellis–van Creveld syndrome in the Amish people is much higher than the frequency in the general population.[53]

Modern synthesis

The modern evolutionary synthesis is based on the concept that populations of organisms have significant genetic variation caused by mutation and by the recombination of genes during sexual reproduction. It defines evolution as the change in allelic frequencies within a population caused by genetic drift, gene flow between sub populations, and natural selection. Natural selection is emphasised as the most important mechanism of evolution; large changes are the result of the gradual accumulation of small changes over long periods of time.[54][55]

The modern evolutionary synthesis is the outcome of a merger of several different scientific fields to produce a more cohesive understanding of evolutionary theory. In the 1920s, Ronald Fisher, J.B.S. Haldane and Sewall Wright combined Darwin's theory of natural selection with statistical models of Mendelian genetics, founding the discipline of population genetics. In the 1930s and 1940s, efforts were made to merge population genetics, the observations of field naturalists on the distribution of species and sub species, and analysis of the fossil record into a unified explanatory model.[56] The application of the principles of genetics to naturally occurring populations, by scientists such as Theodosius Dobzhansky and Ernst Mayr, advanced the understanding of the processes of evolution. Dobzhansky's 1937 work Genetics and the Origin of Species helped bridge the gap between genetics and field biology by presenting the mathematical work of the population geneticists in a form more useful to field biologists, and by showing that wild populations had much more genetic variability with geographically isolated subspecies and reservoirs of genetic diversity in recessive genes than the models of the early population geneticists had allowed for. Mayr, on the basis of an understanding of genes and direct observations of evolutionary processes from field research, introduced the biological species concept, which defined a species as a group of interbreeding or potentially interbreeding populations that are reproductively isolated from all other populations. Both Dobzhansky and Mayr emphasised the importance of subspecies reproductively isolated by geographical barriers in the emergence of new species. The paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson helped to incorporate paleontology with a statistical analysis of the fossil record that showed a pattern consistent with the branching and non-directional pathway of evolution of organisms predicted by the modern synthesis.[54]

Evidence for evolution

Scientific evidence for evolution comes from many aspects of biology and includes fossils, homologous structures, and molecular similarities between species' DNA.

Fossil record

Research in the field of paleontology, the study of fossils, supports the idea that all living organisms are related. Fossils provide evidence that accumulated changes in organisms over long periods of time have led to the diverse forms of life we see today. A fossil itself reveals the organism's structure and the relationships between present and extinct species, allowing paleontologists to construct a family tree for all of the life forms on Earth.[57]

Modern paleontology began with the work of Georges Cuvier. Cuvier noted that, in sedimentary rock, each layer contained a specific group of fossils. The deeper layers, which he proposed to be older, contained simpler life forms. He noted that many forms of life from the past are no longer present today. One of Cuvier’s successful contributions to the understanding of the fossil record was establishing extinction as a fact. In an attempt to explain extinction, Cuvier proposed the idea of "revolutions" or catastrophism in which he speculated that geological catastrophes had occurred throughout the Earth’s history, wiping out large numbers of species.[58] Cuvier's theory of revolutions was later replaced by uniformitarian theories, notably those of James Hutton and Charles Lyell who proposed that the Earth’s geological changes were gradual and consistent.[59] However, current evidence in the fossil record supports the concept of mass extinctions. As a result, the general idea of catastrophism has re-emerged as a valid hypothesis for at least some of the rapid changes in life forms that appear in the fossil records.

A very large number of fossils have now been discovered and identified. These fossils serve as a chronological record of evolution. The fossil record provides examples of transitional species that demonstrate ancestral links between past and present life forms.[60] One such transitional fossil is Archaeopteryx, an ancient organism that had the distinct characteristics of a reptile (such as a long, bony tail and conical teeth) yet also had characteristics of birds (such as feathers and a wishbone). The implication from such a find is that modern reptiles and birds arose from a common ancestor.[61]

Comparative anatomy

The comparison of similarities between organisms of their form or appearance of parts, called their morphology, has long been a way to classify life into closely related groups. This can be done by comparing the structure of adult organisms in different species or by comparing the patterns of how cells grow, divide and even migrate during an organism's development.

Taxonomy

Taxonomy is the branch of biology that names and classifies all living things. Scientists use morphological and genetic similarities to assist them in categorising life forms based on ancestral relationships. For example, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans all belong to the same taxonomic grouping referred to as a family—in this case the family called Hominidae. These animals are grouped together because of similarities in morphology that come from common ancestry (called homology).[62]

Strong evidence for evolution comes from the analysis of homologous structures: structures in different species that no longer perform the same task but which share a similar structure.[63] Such is the case of the forelimbs of mammals. The forelimbs of a human, cat, whale, and bat all have strikingly similar bone structures. However, each of these four species' forelimbs performs a different task. The same bones that construct a bat's wings, which are used for flight, also construct a whale's flippers, which are used for swimming. Such a "design" makes little sense if they are unrelated and uniquely constructed for their particular tasks. The theory of evolution explains these homologous structures: all four animals shared a common ancestor, and each has undergone change over many generations. These changes in structure have produced forelimbs adapted for different tasks.[64]

However, anatomical comparisons can be misleading, as not all anatomical similarities indicate a close relationship. Organisms that share similar environments will often develop similar physical features, a process known as convergent evolution. Both sharks and dolphins have similar body forms, yet are only distantly related—sharks are fish and dolphins are mammals. Such similarities are a result of both populations being exposed to the same selective pressures. Within both groups, changes that aid swimming have been favored. Thus, over time, they developed similar appearances (morphology), even though they are not closely related.[65]

Embryology

In some cases, anatomical comparison of structures in the embryos of two or more species provides evidence for a shared ancestor that may not be obvious in the adult forms. As the embryo develops, these homologies can be lost to view, and the structures can take on different functions. Part of the basis of classifying the vertebrate group (which includes humans), is the presence of a tail (extending beyond the anus) and pharyngeal slits. Both structures appear during some stage of embryonic development but are not always obvious in the adult form.[66]

Because of the morphological similarities present in embryos of different species during development, it was once assumed that organisms re-enact their evolutionary history as an embryo. It was thought that human embryos passed through an amphibian then a reptilian stage before completing their development as mammals. Such a reenactment, often called recapitulation theory, is not supported by scientific evidence. What does occur, however, is that the first stages of development are similar in broad groups of organisms.[67] At very early stages, for instance, all vertebrates appear extremely similar, but do not exactly resemble any ancestral species. As development continues, specific features emerge from this basic pattern.

Vestigial structures

Homology includes a unique group of shared structures referred to as vestigial structures. Vestigial refers to anatomical parts that are of minimal, if any, value to the organism that possesses them. These apparently illogical structures are remnants of organs that played an important role in ancestral forms. Such is the case in whales, which have small vestigial bones that appear to be remnants of the leg bones of their ancestors which walked on land.[68] Humans also have vestigial structures, including the ear muscles, the wisdom teeth, the appendix, the tail bone, body hair (including goose bumps), and the semilunar fold in the corner of the eye.[69]

Biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the geographical distribution of species. Evidence from biogeography, especially from the biogeography of oceanic islands, played a key role in convincing both Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace that species evolved with a branching pattern of common descent.[70] Islands often contain endemic species, species not found anywhere else, but those species are often related to species found on the nearest continent. Furthermore, islands often contain clusters of closely related species that have very different ecological niches, that is have different ways of making a living in the environment. Such clusters form through a process of adaptive radiation where a single ancestral species colonises an island that has a variety of open ecological niches and then diversifies by evolving into different species adapted to fill those empty niches. Well-studied examples include Darwin's finches, a group of 13 finch species endemic to the Galápagos Islands, and the Hawaiian honeycreepers, a group of birds that once, before extinctions caused by humans, numbered 60 species filling diverse ecological roles, all descended from a single finch like ancestor that arrived on the Hawaiian Islands some 4 million years ago.[71] Another example is the Silversword alliance, a group of perennial plant species, also endemic to the Hawaiian Islands, that inhabit a variety of habitats and come in a variety of shapes and sizes that include trees, shrubs, and ground hugging mats, but which can be hybridised with one another and with certain tarweed species found on the west coast of North America; it appears that one of those tarweeds colonised Hawaii in the past, and gave rise to the entire Silversword alliance.[72]

Molecular biology

Every living organism (with the possible exception of RNA viruses) contains molecules of DNA, which carries genetic information. Genes are the pieces of DNA that carry this information, and they influence the properties of an organism. Genes determine an individual's general appearance and to some extent their behavior. If two organisms are closely related, their DNA will be very similar.[73] On the other hand, the more distantly related two organisms are, the more differences they will have. For example, brothers are closely related and have very similar DNA, while cousins share a more distant relationship and have far more differences in their DNA. Similarities in DNA are used to determine the relationships between species in much the same manner as they are used to show relationships between individuals. For example, comparing chimpanzees with gorillas and humans shows that there is as much as a 96 percent similarity between the DNA of humans and chimps. Comparisons of DNA indicate that humans and chimpanzees are more closely related to each other than either species is to gorillas.[74][75][76]

The field of molecular systematics focuses on measuring the similarities in these molecules and using this information to work out how different types of organisms are related through evolution. These comparisons have allowed biologists to build a relationship tree of the evolution of life on Earth.[77] They have even allowed scientists to unravel the relationships between organisms whose common ancestors lived such a long time ago that no real similarities remain in the appearance of the organisms.

Artificial selection

Artificial selection is the controlled breeding of domestic plants and animals. Humans determine which animal or plant will reproduce and which of the offspring will survive; thus, they determine which genes will be passed on to future generations. The process of artificial selection has had a significant impact on the evolution of domestic animals. For example, people have produced different types of dogs by controlled breeding. The differences in size between the Chihuahua and the Great Dane are the result of artificial selection. Despite their dramatically different physical appearance, they and all other dogs evolved from a few wolves domesticated by humans in what is now China less than 15,000 years ago.[78]

Artificial selection has produced a wide variety of plants. In the case of maize (corn), recent genetic evidence suggests that domestication occurred 10,000 years ago in central Mexico.[79] Prior to domestication, the edible portion of the wild form was small and difficult to collect. Today The Maize Genetics Cooperation • Stock Center maintains a collection of more than 10,000 genetic variations of maize that have arisen by random mutations and chromosomal variations from the original wild type.[80]

In artificial selection the new breed or variety that emerges is the one with random mutations attractive to humans, while in natural selection the surviving species is the one with random mutations useful to it in its non-human environment. In both natural and artificial selection the variations are a result of random mutations, and the underlying genetic processes are essentially the same.[81] Darwin carefully observed the outcomes of artificial selection in animals and plants to form many of his arguments in support of natural selection.[82] Much of his book On the Origin of Species was based on these observations of the many varieties of domestic pigeons arising from artificial selection. Darwin proposed that if humans could achieve dramatic changes in domestic animals in short periods, then natural selection, given millions of years, could produce the differences seen in living things today.

Coevolution

Coevolution is a process in which two or more species influence the evolution of each other. All organisms are influenced by life around them; however, in coevolution there is evidence that genetically determined traits in each species directly resulted from the interaction between the two organisms.[73]

An extensively documented case of coevolution is the relationship between Pseudomyrmex, a type of ant, and the acacia, a plant that the ant uses for food and shelter. The relationship between the two is so intimate that it has led to the evolution of special structures and behaviors in both organisms. The ant defends the acacia against herbivores and clears the forest floor of the seeds from competing plants. In response, the plant has evolved swollen thorns that the ants use as shelter and special flower parts that the ants eat.[83] Such coevolution does not imply that the ants and the tree choose to behave in an altruistic manner. Rather, across a population small genetic changes in both ant and tree benefited each. The benefit gave a slightly higher chance of the characteristic being passed on to the next generation. Over time, successive mutations created the relationship we observe today.

Species

Given the right circumstances, and enough time, evolution leads to the emergence of new species. Scientists have struggled to find a precise and all-inclusive definition of species. Ernst Mayr defined a species as a population or group of populations whose members have the potential to interbreed naturally with one another to produce viable, fertile offspring. (The members of a species cannot produce viable, fertile offspring with members of other species).[84] Mayr's definition has gained wide acceptance among biologists, but does not apply to organisms such as bacteria, which reproduce asexually.

Speciation is the lineage-splitting event that results in two separate species forming from a single common ancestral population.[31] A widely accepted method of speciation is called allopatric speciation. Allopatric speciation begins when a population becomes geographically separated.[63] Geological processes, such as the emergence of mountain ranges, the formation of canyons, or the flooding of land bridges by changes in sea level may result in separate populations. For speciation to occur, separation must be substantial, so that genetic exchange between the two populations is completely disrupted. In their separate environments, the genetically isolated groups follow their own unique evolutionary pathways. Each group will accumulate different mutations as well as be subjected to different selective pressures. The accumulated genetic changes may result in separated populations that can no longer interbreed if they are reunited.[31] Barriers that prevent interbreeding are either prezygotic (prevent mating or fertilisation) or postzygotic (barriers that occur after fertilisation). If interbreeding is no longer possible, then they will be considered different species.[85] The result of four billion years of evolution is the diversity of life around us, with an estimated 1.75 million different species in existence today.[24][86]

Usually the process of speciation is slow, occurring over very long time spans; thus direct observations within human life-spans are rare. However speciation has been observed in present-day organisms, and past speciation events are recorded in fossils.[87][88][89] Scientists have documented the formation of five new species of cichlid fishes from a single common ancestor that was isolated fewer than 5,000 years ago from the parent stock in Lake Nagubago.[90] The evidence for speciation in this case was morphology (physical appearance) and lack of natural interbreeding. These fish have complex mating rituals and a variety of colorations; the slight modifications introduced in the new species have changed the mate selection process and the five forms that arose could not be convinced to interbreed.[91]

Mechanism

The theory of evolution is widely accepted among the scientific community, serving to link the diverse specialty areas of biology.[34] Evolution provides the field of biology with a solid scientific base. The significance of evolutionary theory is summarised by Theodosius Dobzhansky as "nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution."[92][93] Nevertheless, the theory of evolution is not static. There is much discussion within the scientific community concerning the mechanisms behind the evolutionary process. For example, the rate at which evolution occurs is still under discussion. In addition, there are conflicting opinions as to which is the primary unit of evolutionary change—the organism or the gene.

Rate of change

Darwin and his contemporaries viewed evolution as a slow and gradual process. Evolutionary trees are based on the idea that profound differences in species are the result of many small changes that accumulate over long periods.

Gradualism had its basis in the works of the geologists James Hutton and Charles Lyell. Hutton's view suggests that profound geological change was the cumulative product of a relatively slow continuing operation of processes which can still be seen in operation today, as opposed to catastrophism which promoted the idea that sudden changes had causes which can no longer be seen at work. A uniformitarian perspective was adopted for biological changes. Such a view can seem to contradict the fossil record, which often shows evidence of new species appearing suddenly, then persisting in that form for long periods. In the 1970s paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould developed a theoretical model that suggests that evolution, although a slow process in human terms, undergoes periods of relatively rapid change (ranging between 50,000 and 100,000 years)[94] alternating with long periods of relative stability. Their theory is called punctuated equilibrium and explains the fossil record without contradicting Darwin's ideas.[95]

Unit of change

A common unit of selection in evolution is the organism. Natural selection occurs when the reproductive success of an individual is improved or reduced by an inherited characteristic, and reproductive success is measured by the number of an individual's surviving offspring. The organism view has been challenged by a variety of biologists as well as philosophers. Richard Dawkins proposes that much insight can be gained if we look at evolution from the gene's point of view; that is, that natural selection operates as an evolutionary mechanism on genes as well as organisms.[96] In his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene, he explains:

| “ | Individuals are not stable things, they are fleeting. Chromosomes too are shuffled to oblivion, like hands of cards soon after they are dealt. But the cards themselves survive the shuffling. The cards are the genes. The genes are not destroyed by crossing-over, they merely change partners and march on. Of course they march on. That is their business. They are the replicators and we are their survival machines. When we have served our purpose we are cast aside. But genes are denizens of geological time: genes are forever.[97] | ” |

Others view selection working on many levels, not just at a single level of organism or gene; for example, Stephen Jay Gould called for a hierarchical perspective on selection.[98]

See also

References

- ↑ "Age of the Earth". United States Geological Survey. July 9, 2007. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

- ↑ Dalrymple 2001, pp. 205–221

- ↑ Manhesa, Gérard; Allègre, Claude J.; Dupréa, Bernard; Hamelin, Bruno (May 1980). "Lead isotope study of basic-ultrabasic layered complexes: Speculations about the age of the earth and primitive mantle characteristics". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 47 (3): 370–382. Bibcode:1980E&PSL..47..370M. ISSN 0012-821X. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(80)90024-2.

- ↑ Schopf, J. William; Kudryavtsev, Anatoliy B.; Czaja, Andrew D.; Tripathi, Abhishek B. (October 5, 2007). "Evidence of Archean life: Stromatolites and microfossils". Precambrian Research. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 158 (3–4): 141–155. ISSN 0301-9268. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2007.04.009.

- ↑ Schopf, J. William (June 29, 2006). "Fossil evidence of Archaean life". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. London: Royal Society. 361 (1470): 869–885. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1578735

. PMID 16754604. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1834.

. PMID 16754604. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1834. - ↑ Raven & Johnson 2002, p. 68

- ↑ Borenstein, Seth (November 13, 2013). "Oldest fossil found: Meet your microbial mom". Excite. Yonkers, NY: Mindspark Interactive Network. Associated Press. Retrieved 2015-05-30.

- ↑ Pearlman, Jonathan (November 13, 2013). "'Oldest signs of life on Earth found'". The Daily Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- ↑ Noffke, Nora; Christian, Daniel; Wacey, David; Hazen, Robert M. (November 16, 2013). "Microbially Induced Sedimentary Structures Recording an Ancient Ecosystem in the ca. 3.48 Billion-Year-Old Dresser Formation, Pilbara, Western Australia". Astrobiology. New Rochelle, NY: Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. 13 (12): 1103–1124. Bibcode:2013AsBio..13.1103N. ISSN 1531-1074. PMC 3870916

. PMID 24205812. doi:10.1089/ast.2013.1030.

. PMID 24205812. doi:10.1089/ast.2013.1030. - ↑ Ohtomo, Yoko; Kakegawa, Takeshi; Ishida, Akizumi; et al. (January 2014). "Evidence for biogenic graphite in early Archaean Isua metasedimentary rocks". Nature Geoscience. London: Nature Publishing Group. 7 (1): 25–28. Bibcode:2014NatGe...7...25O. ISSN 1752-0894. doi:10.1038/ngeo2025.

- 1 2 Borenstein, Seth (19 October 2015). "Hints of life on what was thought to be desolate early Earth". Excite. Yonkers, NY: Mindspark Interactive Network. Associated Press. Retrieved 2015-10-20.

- ↑ Bell, Elizabeth A.; Boehnike, Patrick; Harrison, T. Mark; et al. (19 October 2015). "Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 112: 201517557. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 4664351

. PMID 26483481. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517557112. Retrieved 2015-10-20. Early edition, published online before print.

. PMID 26483481. doi:10.1073/pnas.1517557112. Retrieved 2015-10-20. Early edition, published online before print. - ↑ McKinney 1997, p. 110

- ↑ Stearns, Beverly Peterson; Stearns, S. C.; Stearns, Stephen C. (2000). Watching, from the Edge of Extinction. Yale University Press. p. preface x. ISBN 978-0-300-08469-6. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ↑ Novacek, Michael J. (November 8, 2014). "Prehistory’s Brilliant Future". The New York Times. New York: The New York Times Company. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- ↑ Miller & Spoolman 2012, p. 62

- ↑ Mora, Camilo; Tittensor, Derek P.; Adl, Sina; et al. (August 23, 2011). "How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean?". PLOS Biology. San Francisco, CA: PLOS. 9 (8): e1001127. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 3160336

. PMID 21886479. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127.

. PMID 21886479. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127. - ↑ Staff (2 May 2016). "Researchers find that Earth may be home to 1 trillion species". National Science Foundation. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ↑ "Misconceptions about evolution". Understanding Evolution. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- ↑ Futuyma 2005a

- 1 2 Gould 2002

- 1 2 Gregory, T. Ryan (June 2009). "Understanding Natural Selection: Essential Concepts and Common Misconceptions". Evolution: Education and Outreach. New York: Springer Science+Business Media. 2 (2): 156–175. ISSN 1936-6434. doi:10.1007/s12052-009-0128-1. Retrieved 2015-01-07.

- ↑ "Welcome to Evolution 101!". Understanding Evolution. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- 1 2 Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (June 29, 2006). "Cell evolution and Earth history: stasis and revolution". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. London: Royal Society. 361 (1470): 969–1006. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1578732

. PMID 16754610. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1842.

. PMID 16754610. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1842. - ↑ Garvin-Doxas, Kathy; Klymkowsky, Michael W. (Summer 2008). Alberts, Bruce, ed. "Understanding Randomness and its Impact on Student Learning: Lessons Learned from Building the Biology Concept Inventory (BCI)". CBE—Life Sciences Education. Bethesda, MD: American Society for Cell Biology. 7 (2): 227–233. ISSN 1931-7913. PMC 2424310

. PMID 18519614. doi:10.1187/cbe.07-08-0063.

. PMID 18519614. doi:10.1187/cbe.07-08-0063. - ↑ Raup 1992, p. 210

- ↑ Rhee, Seung Yon. "Gregor Mendel (1822-1884)". Access Excellence. Atlanta, GA: National Health Museum. Retrieved 2015-01-07.

- ↑ Farber 2000, p. 136

- ↑ Darwin 2005

- 1 2 Eldredge, Niles (Spring 2006). "Confessions of a Darwinist". Virginia Quarterly Review. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia. 82 (2): 32–53. ISSN 0042-675X. Retrieved 2015-01-07.

- 1 2 3 Quammen, David (November 2004). "Was Darwin Wrong?". National Geographic (Online extra). Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISSN 0027-9358. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- 1 2 van Wyhe, John (2002). "Charles Darwin: gentleman naturalist". The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. OCLC 74272908. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ↑ van Wyhe, John (2002). "Fertilisation of Orchids". The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. OCLC 74272908. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- 1 2 Delgado, Cynthia (July 28, 2006). "Finding the Evolution in Medicine". NIH Record. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. 58 (15): 1, 8–9. ISSN 1057-5871. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- ↑ Futuyma 2005b, pp. 93–98

- ↑ Darwin 1872, p. 108, "Effects of the increased Use and Disuse of Parts, as controlled by Natural Selection"

- ↑ Ghiselin, Michael T. (September–October 1994). "The Imaginary Lamarck: A Look at Bogus 'History' in Schoolbooks". The Textbook Letter. Sausalito, CA: The Textbook League. OCLC 23228649. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ↑ "Sex and genetic shuffling". Understanding Evolution. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-01-08.

- ↑ "Gene flow". Understanding Evolution. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-01-08.

- ↑ Gould 1980, p. 24

- ↑ Bejder, Lars; Hall, Brian K. (November 2002). "Limbs in whales and limblessness in other vertebrates: mechanisms of evolutionary and developmental transformation and loss". Evolution & Development. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology. 4 (6): 445–458. ISSN 1520-541X. PMID 12492145. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142X.2002.02033.x.

- ↑ Boughner, Julia C.; Buchtová, Marcela; Fu, Katherine; et al. (June 25, 2007). "Embryonic development of Python sebae – I: Staging criteria and macroscopic skeletal morphogenesis of the head and limbs". Zoology. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 110 (3): 212–230. ISSN 0944-2006. PMID 17499493. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2007.01.005.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions About Evolution". Evolution Library (Web resource). Evolution. Boston, MA: WGBH Educational Foundation; Clear Blue Sky Productions, Inc. 2001. OCLC 48165595. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ↑ "A Modern Mass Extinction?". Evolution Library (Web resource). Evolution. Boston, MA: WGBH Educational Foundation; Clear Blue Sky Productions, Inc. 2001. OCLC 48165595. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ↑ Bambach, Richard K.; Knoll, Andrew H.; Wang, Steve C. (December 2004). "Origination, extinction, and mass depletions of marine diversity" (PDF). Paleobiology. Boulder, CO: Paleontological Society. 30 (4): 522–542. ISSN 0094-8373. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0522:OEAMDO>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Futuyma 1998, p. Glossary

- ↑ Ellstrand, Norman C.; Elam, Diane R. (November 1993). "Population Genetic Consequences of Small Population Size: Implications for Plant Conservation". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews. 24: 217–242. ISSN 1545-2069. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.24.110193.001245.

- ↑ Ewens 2004

- 1 2 Campbell & Reece 2002, pp. 445–463

- ↑ Robinson, Richard, ed. (2003). "Population Bottleneck". Genetics. New York: Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 0-02-865606-7. LCCN 2002003560. OCLC 49278650. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- ↑ Futuyma 1998, pp. 303–304

- ↑ Hoelzel, A. Rus; Fleischer, Robert C.; Campagna, Claudio; et al. (July 2002). "Impact of a population bottleneck on symmetry and genetic diversity in the northern elephant seal". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell on behalf of the European Society for Evolutionary Biology. 15 (4): 567–575. ISSN 1010-061X. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00419.x.

- ↑ "Genetic Drift and the Founder Effect". Evolution Library (Web resource). Evolution. Boston, MA: WGBH Educational Foundation; Clear Blue Sky Productions, Inc. 2001. OCLC 48165595. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- 1 2 Larson 2004, pp. 231–237

- ↑ Moran, Laurance (January 22, 1993). "The Modern Synthesis of Genetics and Evolution". TalkOrigins Archive. Houston, TX: The TalkOrigins Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- ↑ Bowler 2003, pp. 325–339

- ↑ "The Fossil Record - Life's Epic". The Virtual Fossil Museum. Roger Perkins. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ↑ Tattersall 1995, pp. 5–6

- ↑ Lyell 1830, p. 76

- ↑ NAS 2008, p. 22

- ↑ Gould 1995, p. 360

- ↑ Diamond 1992, p. 16

- 1 2 "Glossary". Evolution Library (Web resource). Evolution. Boston, MA: WGBH Educational Foundation; Clear Blue Sky Productions, Inc. 2001. OCLC 48165595. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ↑ Mayr 2001, pp. 25–27

- ↑ Johnson, George B. "Convergent and Divergent Evolution". Dr. George Johnson's Backgrounders. St. Louis, MO: Txtwriter, Inc. Archived from the original on 2008-03-10. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- ↑ Weichert & Presch 1975, p. 8

- ↑ Miller, Kenneth R.; Levine, Joseph (1997). "Haeckel and his Embryos: A Note on Textbooks". Evolution Resources. Rehoboth, MA: Miller And Levine Biology. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- ↑ Theobald, Douglas (2004). "29+ Evidences for Macroevolution" (PDF). TalkOrigins Archive. Houston, TX: The TalkOrigins Foundation, Inc. Part 2: "Whales with hindlimbs". Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ↑ Johnson, George B. "Vestigial Structures". Dr. George Johnson's Backgrounders. St. Louis, MO: Txtwriter, Inc. Archived from the original on 2008-03-10. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- ↑ Bowler 2003, pp. 150–151,174

- ↑ Coyne 2009, pp. 102–103

- ↑ Carr, Gerald D. "Adaptive Radiation and Hybridization in the Hawaiian Silversword Alliance". Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Botany Department. Retrieved 2015-01-10.

- 1 2 NAS 1998, "Evolution and the Nature of Science"

- ↑ Lovgren, Stefan (August 31, 2005). "Chimps, Humans 96 Percent the Same, Gene Study Finds". National Geographic News. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ↑ Carroll, Grenier & Weatherbee 2005

- ↑ "Cons 46-Way Track Settings". UCSC Genome Bioinformatics. Santa Cruz, CA: University of California, Santa Cruz. Retrieved 2015-01-10.

- ↑ Ciccarelli, Francesca D.; Doerks, Tobias; von Mering, Christian; et al. (March 3, 2006). "Toward Automatic Reconstruction of a Highly Resolved Tree of Life". Science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science. 311 (5765): 1283–1287. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1283C. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16513982. doi:10.1126/science.1123061.

- ↑ McGourty, Christine (November 22, 2002). "Origin of dogs traced". BBC News. London: BBC. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ↑ Hall, Hardy (November 7, 2005). "Transgene Escape: Are Traditional Corn Varieties In Mexico Threatened by Transgenic Corn Crops". The Scientific Creative Quarterly. Vancouver and Kelowna, BC: University of British Columbia. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ↑ "Maize COOP Information". National Plant Germplasm System. United States Department of Agriculture; Agricultural Research Service. November 23, 2010. Retrieved 2015-01-10.

- ↑ Silverman, David (2002). "Better Books by Trial and Error". Life's Big Instruction Book. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ↑ Wilner, Eduardo (March 2006). "Darwin's artificial selection as an experiment". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. 37 (1): 26–40. ISSN 1369-8486. PMID 16473266. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2005.12.002.

- ↑ Janzen, Daniel H. (1974). "Swollen-Thorn Acacias of Central America" (PDF). Smithsonian Contributions to Botany. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. 13. ISSN 0081-024X. OCLC 248582653. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ↑ Mayr 2001, pp. 165–169

- ↑ Sulloway, Frank J. (December 2005). "The Evolution of Charles Darwin". Smithsonian. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISSN 0037-7333. Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- ↑ "How many species are there?". Enviroliteracy.org. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Literacy Council. June 17, 2008. Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- ↑ Jiggins, Chris D.; Bridle, Jon R. (March 2004). "Speciation in the apple maggot fly: a blend of vintages?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Cell Press. 19 (3): 111–114. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 16701238. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2003.12.008.

- ↑ Boxhorn, Joseph (September 1, 1995). "Observed Instances of Speciation". TalkOrigins Archive. Houston, TX: The TalkOrigins Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ↑ Weinberg, James R.; Starczak, Victoria R.; Jörg, Daniele (August 1992). "Evidence for Rapid Speciation Following a Founder Event in the Laboratory". Evolution. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons on behalf of the Society for the Study of Evolution. 46 (4): 1214–1220. ISSN 0014-3820. JSTOR 2409766. doi:10.2307/2409766.

- ↑ Mayr 1970, p. 348

- ↑ Mayr 1970

- ↑ Dobzhansky, Theodosius (March 1973). "Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution". The American Biology Teacher. McLean, VA: National Association of Biology Teachers. 35 (3): 125–129. doi:10.2307/4444260.

- ↑ Scott, Eugenie C. (October 17, 2008) [Originally published on PBS Online, May 2000]. "Cans and Can'ts of Teaching Evolution". National Center for Science Education (Blog). Berkeley, CA: National Center for Science Education. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ↑ Ayala, Francisco J. (2005). "The Structure of Evolutionary Theory: on Stephen Jay Gould's Monumental Masterpiece". Theology and Science. London: Routledge. 3 (1): 104. ISSN 1474-6700. doi:10.1080/14746700500039800.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay (August 1991). "Opus 200" (PDF). Natural History. Research Triangle Park, NC: Natural History Magazine, Inc. 100 (8): 12–18. ISSN 0028-0712.

- ↑ Wright, Sewall (September 1980). "Genic and Organismic Selection". Evolution. The Society for the Study of Evolution. 34 (5): 825–843. JSTOR 2407990. doi:10.2307/2407990.

- ↑ Dawkins 1976, p. 35

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay; Lloyd, Elisabeth A. (October 12, 1999). "Individuality and adaptation across levels of selection: How shall we name and generalise the unit of Darwinism?". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. 96 (21): 11904–11909. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9611904G. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 18385

. PMID 10518549. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.21.11904.

. PMID 10518549. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.21.11904.

Bibliography

- Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: The History of an Idea (3rd completely rev. and expanded ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23693-9. LCCN 2002007569. OCLC 49824702.

- Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. (2002). "The Evolution of Populations". Biology. 6th. San Francisco, CA: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-6624-5. LCCN 2001047033. OCLC 47521441.

- Carroll, Sean B.; Grenier, Jennifer K.; Weatherbee, Scott D. (2005). From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1950-0. LCCN 2003027991. OCLC 53972564.

- Coyne, Jerry A. (2009). Why Evolution is True. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-02053-9. LCCN 2008033973. OCLC 233549529.

- Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". In Lewis, C. L. E.; Knell, S. J. The Age of the Earth: from 4004 BC to AD 2002. Geological Society Special Publication. 190. London: Geological Society of London. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205D. ISBN 1-86239-093-2. ISSN 0305-8719. LCCN 2003464816. OCLC 48570033. doi:10.1144/gsl.sp.2001.190.01.14.

- Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1st ed.). London: John Murray. LCCN 06017473. OCLC 741260650.

- Darwin, Charles (1872). The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (6th ed.). London: John Murray. LCCN 13003393. OCLC 228738610.

- Darwin, Charles (2005). Darwin: The Indelible Stamp: The Evolution of an Idea. Edited, with foreword and commentary by James D. Watson. Philadelphia, PA: Running Press. ISBN 0-7624-2136-3. OCLC 62172858.

- Dawkins, Richard (1976). The Selfish Gene (1st ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-857519-X. LCCN 76029168. OCLC 2681149.

- Diamond, Jared (1992). The Third Chimpanzee: The Evolution and Future of the Human Animal (1st ed.). New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-018307-1. LCCN 91050455. OCLC 24246928.

- Ewens, Warren J. (2004). Mathematical Population Genetics. Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics. I. Theoretical Introduction (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag New York. ISBN 0-387-20191-2. LCCN 2003065728. OCLC 53231891.

- Farber, Paul Lawrence (2000). Finding Order in Nature: The Naturalist Tradition from Linnaeus to E. O. Wilson. Johns Hopkins Introductory Studies in the History of Science. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6390-2. LCCN 99089621. OCLC 43115207.

- Futuyma, Douglas J. (1998). Evolutionary Biology (3rd ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-189-9. LCCN 97037947. OCLC 37560100.

- Futuyma, Douglas J. (2005a). Evolution. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-187-2. LCCN 2004029808. OCLC 57311264.

- Futuyma, Douglas J. (2005b). "The Nature of Natural Selection". In Cracraft, Joel; Bybee, Rodger W. Evolutionary Science and Society: Educating a New Generation (PDF). Colorado Springs, CO: Biological Sciences Curriculum Study. ISBN 1-929614-23-3. OCLC 64228003. Retrieved 2014-12-06. "Revised Proceedings of the BSCS, AIBS Symposium November 2004, Chicago, IL"

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1980). The Panda's Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-01380-4. LCCN 80015952. OCLC 6331415.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1995). Dinosaur in a Haystack: Reflections in Natural History. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 0-517-70393-9. LCCN 95051333. OCLC 33892123.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00613-5. LCCN 2001043556. OCLC 47869352.

- Larson, Edward J. (2004). Evolution: The Remarkable History of a Scientific Theory. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-64288-9. LCCN 2003064888. OCLC 53483597.

- Lyell, Charles (1830). Principles of Geology, Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation. London: John Murray. LCCN 45042424. OCLC 670356586.

- Mayr, Ernst (1970). Populations, Species, and Evolution: An Abridgment of Animal Species and Evolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-69010-9. LCCN 79111486. OCLC 114063.

- Mayr, Ernst (2001). What Evolution Is. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04426-3. LCCN 2001036562. OCLC 47443814.

- McKinney, Michael L. (1997). "How do rare species avoid extinction? A paleontological view". In Kunin, William E.; Gaston, Kevin J. The Biology of Rarity: Causes and consequences of rare—common differences (1st ed.). London; New York: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 0-412-63380-9. LCCN 96071014. OCLC 36442106.

- Miller, G. Tyler; Spoolman, Scott E. (2012). Environmental Science (14th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-1-111-98893-7. LCCN 2011934330. OCLC 741539226.

- National Academy of Sciences (1998). Teaching About Evolution and the Nature of Science. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. ISBN 0-309-06364-7. LCCN 98016100. OCLC 245727856. Retrieved 2015-01-10.

- National Academy of Sciences; Institute of Medicine (2008). Science, Evolution, and Creationism. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-10586-6. LCCN 2007015904. OCLC 123539346. Retrieved 2014-07-31.

- Raup, David M. (1992) [Originally published 1991]. Extinction: Bad Genes or Bad Luck?. Introduction by Stephen Jay Gould. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30927-4. LCCN 90027192. OCLC 28725488.

- Raven, Peter H.; Johnson, George B. (2002). Biology (6th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-112261-3. LCCN 2001030052. OCLC 45806501.

- Tattersall, Ian (1995). The Fossil Trail: How We Know What We Think We Know About Human Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506101-2. LCCN 94031633. OCLC 30972979.

- Weichert, Charles K.; Presch, William (1975). Elements of Chordate Anatomy. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-069008-1. LCCN 74017151. OCLC 1032188.

Further reading

- Charlesworth, Brian; Charlesworth, Deborah (2003). Evolution: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280251-8. LCCN 2003272247. OCLC 51668497.

- Ellis, R. John (2010). How Science Works: Evolution: A Student Primer. Dordrecht; New York: Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-3182-2. LCCN 2009941981. OCLC 465370643. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3183-9.

- Horvitz, Leslie Alan (2002). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Evolution. Indianapolis, IN: Alpha Books. ISBN 0-02-864226-0. LCCN 2001094735. OCLC 48402612.

- Krukonis, Greg; Barr, Tracy L. (2008). Evolution For Dummies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-11773-6. LCCN 2008922285. OCLC 183916075.

- Pallen, Mark J. (2009). The Rough Guide to Evolution. Rough Guides Reference Guides. London; New York: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-85828-946-5. LCCN 2009288090. OCLC 233547316.

- Sís, Peter (2003). The Tree of Life: A Book Depicting the Life of Charles Darwin, Naturalist, Geologist & Thinker (1st ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-45628-3. LCCN 2002040706. OCLC 50960680.

- Thomson, Keith (2005). Fossils: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280504-1. LCCN 2005022027. OCLC 61129133.

- Villarreal, Luis (2005). Viruses and the Evolution of Life. ASM Press.

- Zimmer, Carl (2010). The Tangled Bank: An Introduction to Evolution. Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts & Company Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9815194-7-0. LCCN 2009021802. OCLC 403851918.

External links

- "Introduction to evolution and natural selection". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- Brain, Marshall (July 25, 2001). "How Evolution Works". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 2015-01-06.

- "The Talk.Origins Archive: Evolution FAQs". TalkOrigins Archive. Houston, TX: The TalkOrigins Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2015-01-12.

- Melton, Lisa (2007); Reza, Julie (2007); Jones, Ian (2014); Staves, Jennifer Trent (2014) (January 2007). "Evolution". Big Picture. London: Wellcome Trust. ISSN 1745-7777. Retrieved 2015-01-06. Updated for the Web in 2014.

- "Understanding Evolution: your one-stop resource for information on evolution". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 2015-01-08.

- "An Introduction To Evolution". Vectors (Web resource). Greg Goebel. Retrieved 2010-06-01.