Interstate Commerce Commission

|

Seal | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | February 4, 1887 |

| Dissolved | January 1, 1996 |

| Superseding agency | |

| Jurisdiction | United States |

| Key documents |

|

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) was a regulatory agency in the United States created by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. The agency's original purpose was to regulate railroads (and later trucking) to ensure fair rates, to eliminate rate discrimination, and to regulate other aspects of common carriers, including interstate bus lines and telephone companies. Congress expanded ICC authority to regulate other modes of commerce beginning in 1906. The agency was abolished in 1995, and its remaining functions were transferred to the Surface Transportation Board.

The Commission's five members were appointed by the President with the consent of the United States Senate. This was the first independent agency (or so-called Fourth Branch).

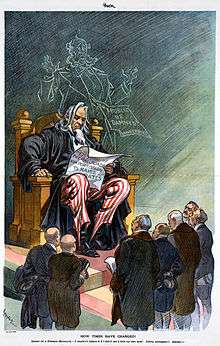

Creation

The ICC was established by the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland.[1] The creation of the commission was the result of widespread and longstanding anti-railroad agitation. Western farmers, specifically those of the Grange Movement, were the dominant force behind the unrest, but Westerners generally — especially those in rural areas — believed that the railroads possessed economic power that they systematically abused. A central issue was rate discrimination between similarly situated customers and communities.[2]:42ff Other potent issues included alleged attempts by railroads to obtain influence over city and state governments and the widespread practice of granting free transportation in the form of yearly passes to opinion leaders (elected officials, newspaper editors, ministers, and so on) so as to dampen any opposition to railroad practices.

Various sections of the Interstate Commerce Act banned "personal discrimination" and required shipping rates to be "just and reasonable."

President Cleveland appointed Thomas M. Cooley as the first chairman of the ICC. Cooley had been Dean of the University of Michigan Law School and Chief Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court.[3]

Initial implementation and legal challenges

The Commission had a troubled start because the law that created it failed to give it adequate enforcement powers.

- "The Commission is, or can be made, of great use to the railroads. It satisfies the popular clamor for a government supervision of the railroads, while at the same time that supervision is almost entirely nominal." - William H. H. Miller, US Attorney General, circa 1889.[4]

Following passage of the 1887 act, the ICC proceeded to set maximum shipping rates for railroads. However, in the late 1890s several railroads challenged the agency's ratemaking authority in litigation, and the courts severely limited the ICC's powers.[2]:90ff[5]

Expansion of ICC authority

Congress expanded the commission's powers through subsequent legislation. The 1893 Railroad Safety Appliance Act gave the ICC jurisdiction over railroad safety, removing this authority from the states, and this was followed with amendments in 1903 and 1910.[6] The Hepburn Act of 1906 authorized the ICC to set maximum railroad rates, and extended the agency's authority to cover bridges, terminals, ferries, sleeping cars, express companies and oil pipelines.[7]

A long-standing controversy was how to interpret language in the Act that banned long haul-short haul fare discrimination. The Mann-Elkins Act of 1910 addressed this question by strengthening ICC authority over railroad rates, This amendment also expanded the ICC's jurisdiction to include regulation of telephone, telegraph and wireless companies.[8]

The Valuation Act of 1913 required the ICC to organize a Bureau of Valuation that would assess the value of railroad property. This information would be used to set rates.[9]

In 1934, Congress transferred the telecommunications authority to the new Federal Communications Commission.[10]

In 1935, Congress passed the Motor Carrier Act, which extended ICC authority to regulate interstate bus lines and trucking as common carriers.[11]

Ripley Plan to consolidate railroads into regional systems

The Transportation Act of 1920 directed the Interstate Commerce Commission to prepare and adopt a plan for the consolidation of the railway properties of the United States into a limited number of systems. Between 1920 and 1923, William Z. Ripley, a professor of political economy at Harvard University, wrote up ICC's plan for the regional consolidation of the U.S. railways.[12] His plan became known as the Ripley Plan. In 1929 the ICC published Ripley's Plan under the title Complete Plan of Consolidation. Numerous hearings were held by ICC regarding the plan under the topic "In the Matter of Consolidation of the Railways of the United States into a Limited Number of Systems".[13]

The proposed 21 regional railroads were as follows:

- Boston and Maine Railroad; Maine Central Railroad; Bangor and Aroostook Railroad; Delaware and Hudson Railroad

- New Haven Railroad; New York, Ontario and Western Railway; Lehigh and Hudson River Railway; Lehigh and New England Railroad

- New York Central Railroad; Rutland Railroad; Virginian Railway; Chicago, Attica and Southern Railroad

- Pennsylvania Railroad; Long Island Rail Road

- Baltimore and Ohio Railroad; Central Railroad of New Jersey; Reading Railroad; Buffalo and Susquehanna Railroad; Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh Railway; 50% of Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad; 50% of Detroit and Toledo Shore Line Railroad; 50% of Monon Railroad; Chicago and Alton Railroad (Alton Railroad)

- Chesapeake and Ohio-Nickel Plate Road; Hocking Valley Railway; Erie Railroad; Pere Marquette Railway; Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad; Bessemer and Lake Erie Railroad; Chicago and Illinois Midland Railroad; 50% of Detroit and Toledo Shore Line Railroad

- Wabash-Seaboard Air Line Railway; Lehigh Valley Railroad; Wheeling and Lake Erie Railway; Pittsburgh and West Virginia Railway; Western Maryland Railway; Akron, Canton and Youngstown Railway; Norfolk and Western Railway; 50% of Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad; Toledo, Peoria and Western Railroad; Ann Arbor Railroad; 50% of Winston-Salem Southbound Railway

- Atlantic Coast Line Railroad; Louisville and Nashville Railroad; Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis Railway; Clinchfield Railroad; Atlanta, Birmingham and Coast Railroad; Mobile and Northern Railroad; New Orleans Great Northern Railroad; 25% of Chicago, Indianapolis and Louisville Railway (Monon Railway); 50% of Winston-Salem Southbound Railway

- Southern Railway; Norfolk Southern Railroad; Tennessee Central Railway (east of Nashville); Florida East Coast Railway; 25% of Chicago, Indianapolis and Louisville Railway (Monon Railway)

- Illinois Central Railroad; Central of Georgia Railway; Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway; Tennessee Central Railway (west of Nashville); St. Louis Southwestern Railway (Cotton Belt Railway); Atlanta and St. Andrews Bay Railroad

- Chicago and North Western Railway; Chicago and Eastern Illinois Railway; Litchfield and Madison Railway; Mobile and Ohio Railroad; Columbus and Greenville Railway; Lake Superior and Ishpeming Railroad

- Great Northern-Northern Pacific Railway; Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway; 50% of Butte, Anaconda and Pacific Railway

- Milwaukee Road; Escanaba and Lake Superior Railroad; Duluth, Missabe and Northern Railway; Duluth and Iron Range Railroad; 50% of Butte, Anaconda and Pacific Railway; trackage rights on Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway to Portland, Oregon.

- Burlington Route; Colorado and Southern Railway; Fort Worth and Denver Railway; Green Bay and Western Railroad; Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad; 50% of Trinity and Brazos Valley Railroad; Oklahoma City-Ada-Atoka Railway

- Union Pacific Railroad; Kansas City Southern Railway

- Southern Pacific Railroad

- Santa Fe Railway; Chicago Great Western Railway; Kansas City, Mexico and Orient Railway; Missouri and North Arkansas Railway; Midland Valley Railroad; Minneapolis, Northfield and Southern Railway

- Missouri Pacific Railroad; Texas and Pacific Railway; Kansas, Oklahoma and Gulf Railway; Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad; Denver and Salt Lake Railroad; Western Pacific Railroad; Fort Smith and Western Railroad

- Rock Island-Frisco Railway; Alabama, Tennessee and Northern Railroad; 50% of Trinity and Brazos Valley Railroad; Louisiana and Arkansas Railway; Meridian and Bigbee Railroad

- Canadian National; Detroit, Grand Haven and Milwaukee Railway; Grand Trunk Western Railway

- Canadian Pacific; Soo Line; Duluth, South Shore and Atlantic Railway; Mineral Range Railroad

Terminal railroads proposed

There were 100 terminal railroads that were also proposed. Below is a sample:

- Toledo Terminal Railroad; Detroit Terminal Railroad; Kankakee & Seneca Railroad

- Indianapolis Union Railway; Boston Terminal; Ft. Wayne Union Railway; Norfolk & Portsmouth Belt Line Railroad

- Toledo, Angola & Western Railway

- Akron and Barberton Belt Railroad; Canton Railroad; Muskegon Railway & Navigation

- Philadelphia Belt Line Railroad; Fort Street Union Depot; Detroit Union Railroad Depot & Station; 15 other properties throughout the United States

- St. Louis & O'Fallon Railway; Detroit & Western Railway; Flint Belt Railroad; 63 other properties throughout the United States

- Youngstown & Northern Railroad; Delray Connecting Railroad; Wyandotte Southern Railroad; Wyandotte Terminal Railroad; South Brooklyn Railway

Plan rejected

Many small railroads failed during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Of those lines that survived, the stronger ones were not interested in supporting the weaker ones.[13] Congress repudiated Ripley's Plan with the Transportation Act of 1940, and the consolidation idea was scrapped.[14]

Racial integration of transport

Although racial discrimination was never a major focus of its efforts, the ICC had to address civil rights issues when passengers filed complaints.

History

- April 28, 1941 - In Mitchell v. United States, the United States Supreme Court rules that discrimination in which a colored man who had paid a first class fare for an interstate journey was compelled to leave that car and ride in a second class car was essentially unjust, and violated the Interstate Commerce Act.[15] The court thus overturns an ICC order dismissing a complaint against an interstate carrier.

- June 3, 1946 - In Morgan v. Virginia, the Supreme Court invalidates provisions of the Virginia Code which require the separation of white and colored passengers where applied to interstate bus transport. The state law is unconstitutional insofar as it is burdening interstate commerce, an area of federal jurisdiction.[16]

- June 5, 1950 - In Henderson v. United States, the Supreme Court rules to abolish segregation of reserved tables in railroad dining cars.[17] The Southern Railway had reserved tables in such a way as to allocate one table conditionally for blacks and multiple tables for whites; a black passenger traveling first-class was not served in the dining car as the one reserved table was in use. The ICC ruled the discrimination to be an error in judgement on the part of an individual dining car steward; both the United States District Court for the District of Maryland and the Supreme Court disagreed, finding the published policies of the railroad itself to be in violation of the Interstate Commerce Act.

- September 1, 1953 - In Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company, Women's Army Corps private Sarah Keys, represented by civil rights lawyer Dovey Roundtree, becomes the first black to challenge the "separate but equal" doctrine in bus segregation before the ICC. While the initial ICC reviewing commissioner declined to accept the case, claiming Brown v. Board of Education (1954) "did not preclude segregation in a private business such as a bus company," Roundtree ultimately prevailed in obtaining a review by the full eleven-person commission.[18]

- November 7, 1955 – ICC bans bus segregation in interstate travel in Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company.[19] This extends the logic of Brown v. Board of Education, a precedent ending the use of "separate but equal" as a defence against discrimination claims in education, to bus travel across state lines.

- December 5, 1960 - In Boynton v. Virginia, the Supreme Court holds that racial segregation in bus terminals is illegal because such segregation violates the Interstate Commerce Act.[20] This ruling, in combination with the ICC's 1955 decision in Keys v. Carolina Coach, effectively outlaws segregation on interstate buses and at the terminals servicing such buses.

- September 23, 1961 - The ICC, at Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy’s insistence, issues new rules ending discrimination in interstate travel. Effective November 1, 1961, six years after the commission's own ruling in Keys v. Carolina Coach Company, all interstate buses required to display a certificate that reads: “Seating aboard this vehicle is without regard to race, color, creed, or national origin, by order of the Interstate Commerce Commission.”

Relationship between regulatory body and the regulated

A friendly relationship between the regulators and the regulated is evident in several early civil rights cases. Throughout the South, railroads had established segregated facilities for sleeping cars, coaches and dining cars. At the same time, the plain language of the Act (forbidding "undue or unreasonable preference" as well as "personal discrimination") could be read as an implied invitation for activist regulators to chip away at racial discrimination.

It shall be unlawful for any common carrier subject to the provisions of this part to make, give, or cause any undue or unreasonable preference or advantage to any particular person, company, firm, corporation, association, locality, port, port district, gateway, transit point, region, district, territory, or any particular description of traffic, in any respect whatsoever; or to subject any particular person, company, firm, corporation, association, locality, port, port district, gateway, transit point, region, district, territory, or any particular description of traffic to any undue or unreasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any respect whatsoever. . .[21]

In at least two landmark cases, however, the Commission sided with the railroads rather than with the African-American passengers who had filed complaints. In both Mitchell v. United States (1941) and Henderson v. United States, the Supreme Court took a more expansive view of the Act than the Commission.[15][17] In 1962, the ICC banned racial discrimination in buses and bus stations, but it did not do so until several months after a binding pro-integration Supreme Court decision Boynton v. Virginia and the Freedom Rides (in which activists engaged in civil disobedience to desegregate interstate buses).

Criticism

The limitation on railroad rates in 1906-07 depreciated the value of railroad securities, a factor in causing the panic of 1907.[22]

Some economists and historians, such as Milton Friedman assert that existing railroad interests took advantage of ICC regulations to strengthen their control of the industry and prevent competition, constituting regulatory capture.[23]

Economist David D. Friedman argues that the ICC always served the railroads as a cartelizing agent and used its authority over other forms of transportation to prevent them, where possible, from undercutting the railroads.[24]

Abolition

Congress passed various deregulation measures in the 1970s and early 1980s which diminished ICC authority, including the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976 ("4R Act"), the Motor Carrier Act of 1980 and the Staggers Rail Act of 1980. Senator Fred R. Harris of Oklahoma was a strong supporter of abolishing the Commission.[25] In December 1995, with most of the ICC's powers had been eliminated or repealed, Congress finally abolished the agency with the ICC Termination Act of 1995.[26] Final Chair Gail McDonald oversaw transferring its remaining functions to a new agency, the U.S. Surface Transportation Board (STB), which reviews merger/acquisitions, rail line abandonments and railroad corporate filings. Regulation of motor carriers is now under the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT), in the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA).

ICC jurisdiction on rail safety (hours of service rules, equipment and inspection standards) was transferred to the USDOT under the Federal Rail Administration per the Federal Rail Safety Act of 1970.

Prior to its abolition, the ICC issued identification numbers to Motor Carriers (bus lines, trucking companies) which it issued licenses. These identification numbers were generally in the form of ICC MC-000000. When the ICC was dissolved, the function of licensing interstate Motor Carriers was transferred to the U.S. Department of Transportation, so now all motor carriers which have federal licenses have a USDOT number such as USDOT 000000.

Legacy

The ICC served as a model for later regulatory efforts. Unlike, for example, state medical boards (historically administered by the doctors themselves), the seven Interstate Commerce Commissioners and their staffs were full-time regulators who could have no economic ties to the industries they regulated. Since 1887, some state and other federal agencies adopted this structure. And, like the ICC, later agencies tended to be organized as multi-headed independent commissions with staggered terms for the commissioners. At the federal level, agencies patterned after the ICC included the Federal Trade Commission (1914), the Federal Communications Commission (1934), the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (1934), the National Labor Relations Board (1935), the Civil Aeronautics Board (1940), Postal Regulatory Commission (1970) and the Consumer Product Safety Commission (1975).

In recent decades, this regulatory structure of independent federal agencies has gone out of fashion. The agencies created after the 1970s generally have single heads appointed by the President and are divisions inside executive Cabinet Departments (e.g., the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (1970) or the Transportation Security Administration (2002)). The trend is the same at the state level, though it is probably less pronounced.

International influence

The Interstate Commerce Commission had a strong influence on the founders of Australia. The Constitution of Australia provides (§§ 101-104; also § 73) for the establishment of an Inter-State Commission, modeled after the United States' Interstate Commerce Commission. However, these provisions have largely not been put into practice; the Commission existed between 1913–1920, and 1975–1989, but never assumed the role which Australia's founders had intended for it.

See also

- Category: Interstate Commerce Commission litigation

- Category: People of the Interstate Commerce Commission

- Civil Aeronautics Board, a comparable body regulating American air travel

- Airline deregulation in the United States, an overview of the CAB's rise and fall

- History of rail transport in the United States

- United States administrative law

References

- ↑ United States. Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, Pub.L. 49–104, 24 Stat. 379, enacted February 4, 1887.

- 1 2 Sharfman, I. Leo (1915). Railway Regulation. Chicago: LaSalle Extension University.

- ↑ "Thomas McIntyre Cooley; 1824-1898". Thomas M. Cooley Law School. Lansing, MI: Western Michigan University. Retrieved 2017-02-25.

- ↑ Thomas Frank, "Politics will undermine regulation plan" Marketplace, American Public Media, June 18, 2009.

- ↑ U.S. Supreme Court. Interstate Commerce Commission v. Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific Railway Co., 167 U.S. 479 (1897).

- ↑ Safety Appliance Act of Mar. 2, 1893, 52nd Congress, 2nd session, ch. 196, 27 Stat. 531. Safety Appliance Act of March 2, 1903, 57th Congress, 2nd session, ch. 976, 32 Stat. 943. Safety Appliance Act of April 14, 1910, 61st Congress, 2nd session, ch. 160, 36 Stat. 298.

- ↑ United States. Hepburn Act of 1906, 59th Congress, Sess. 1, ch. 3591, 34 Stat. 584, approved 1906-06-29.

- ↑ Mann-Elkins Act of 1910, 61st Congress, ch. 309, 36 Stat. 539, approved 1910-06-18.

- ↑ Valuation Act, 62nd Congress, ch. 92, 37 Stat. 701, enacted 1913-03-01.

- ↑ Communications Act of 1934, 73rd Congress, ch. 652, Public Law 416, 48 Stat. 1064, June 19, 1934. 47 U.S.C. Chapter 5.

- ↑ Motor Carrier Act of 1935, 49 Stat. 543, ch. 498, approved 1935-08-09.

- ↑ Miranti, Jr., Paul J. (1996). "Ripley, William Z. (1867-1941)". In Chatfield, Michael; Vangermeersch, Richard. History of Accounting: An International Encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 502–505. ISBN 978-0-815-30809-6.

- 1 2 Kolsrud, Gretchen S., et al (1975). "Review of Recent Railroad Merger History." Appendix B of A Review of National Railroad Issues. Washington: U.S. Office of Technology Assessment. NTIS Document No. PB-250622.

- ↑ Transportation Act of 1940, Sept. 18, 1940, ch. 722, 54 Stat. 898.

- 1 2 Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 80 (1941).

- ↑ Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373 (1946)

- 1 2 Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816 (1950).

- ↑ Challenging the System: Two Army Women Fight for Equality, Judith Bellafaire Ph.D., Curator, Women In Military Service For America Memorial Foundation

- ↑ Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company, 64 MCC 769 (1955).

- ↑ Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U.S. 454 (1960).

- ↑ Interstate Commerce Act, 54 Stat. 902, 49 U.S.C. § 3(1).

- ↑ Edwards, Adolph (1907). The Roosevelt Panic of 1907. New York: Anitrock. p. 66.

- ↑ Friedman, Milton; Friedman, Rose (1990). Free to Choose: A Personal Statement. New York: Harcourt. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-15-633460-0.

- ↑ Friedman, David D. (1989). The Machinery of Freedom. LaSalle, Illinois: Open Court Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 0-8126-9069-9.

- ↑ Walker, Jesse (2009-11-01) Five Faces of Jerry Brown, The American Conservative.

- ↑ ICC Termination Act of 1995, Pub.L. 104–88, 109 Stat. 803, enacted December 29, 1995.

Sources

- Stone, Richard D. (1991). The Interstate Commerce Commission and the railroad industry: a history of regulatory policy. New York: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-93941-0.

- Barnes, Catherine A. (1983). Journey from Jim Crow: The Desegregation of Southern Transit. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-05380-8.

- Catsam, Derek Charles (2009). Freedom's Main Line: The Journey of Reconciliation and the Freedom Rides. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2511-4.

- Kolko, Gabriel (1965). Railroads and Regulation: 1877-1916. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-8885-0.

External links

- Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). "People & Events: Interstate Commerce Commission." (Notes for the television program The American Experience: Streamliners.)

- Historic technical reports from the Interstate Commerce Commission (and other Federal agencies) are available in the Technical Reports Archive and Image Library (TRAIL)

- Records of the Interstate Commerce Commission and Surface Transportation Board in the National Archives (Record Group 134)

-

Johnson, Emory Richard (1922). "Interstate Commerce". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.).

Johnson, Emory Richard (1922). "Interstate Commerce". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.).