Electrotherapy

| Electrotherapy | |

|---|---|

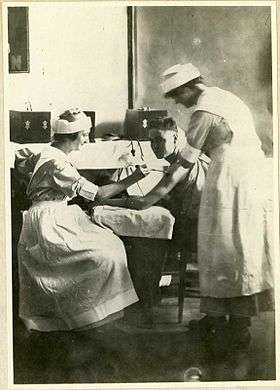

Use of electrical apparatus. Interrupted galvanism used in regeneration of deltoid muscle. First half of the twentieth century. | |

| MeSH | D004599 |

Electrotherapy is the use of electrical energy as a medical treatment.[1] In medicine, the term electrotherapy can apply to a variety of treatments, including the use of electrical devices such as deep brain stimulators for neurological disease. The term has also been applied specifically to the use of electric current to speed wound healing. Additionally, the term "electrotherapy" or "electromagnetic therapy" has also been applied to a range of alternative medical devices and treatments.

It has not been found to be effective in increasing bone healing.[2]

History

The first medical treatments with electricity in London have been recorded as far back as 1767 at Middlesex Hospital in London using a special apparatus. The same was purchased for St. Bartholomew's Hospital only ten years later. The record of uses other than being therapeutic is not clear, however Guy's Hospital has a published list of cases from the earlier 1800s.[3]

See also Oudin coils, in use around 1900.

Muscle stimulation

In 1856 Guillaume Duchenne announced that alternating was superior to direct current for electrotherapeutic triggering of muscle contractions.[4] What he called the 'warming affect' of direct currents irritated the skin, since, at voltage strengths needed for muscle contractions, they cause the skin to blister (at the anode) and pit (at the cathode). Furthermore, with DC each contraction required the current to be stopped and restarted. Moreover, alternating current could produce strong muscle contractions regardless of the condition of the muscle, whereas DC-induced contractions were strong if the muscle was strong, and weak if the muscle was weak.

Since that time almost all rehabilitation involving muscle contraction has been done with a symmetrical rectangular biphasic waveform. During the 1940s, however, the U.S. War Department, investigating the application of electrical stimulation not just to retard and prevent atrophy but to restore muscle mass and strength, employed what was termed galvanic exercise on the atrophied hands of patients who had an ulnar nerve lesion from surgery upon a wound.[5] These galvanic exercises employed a monophasic wave form, direct current.

Cancer treatment

In the field of cancer treatment, DC electrotherapy showed promise as early as 1959, when a study published in the journal Science reported total destruction of tumor in 60% of subjects, which was very noteworthy for an initial study.[6] In 1985, the journal Cancer Research published the most remarkable such study, reporting 98% shrinkage of tumor in animal subjects on being treated with DC electrotherapy for only five hours over five days.[7] The mechanism for the effectiveness of DC electrotherapy in treating cancer was suggested in an article published in 1997.[8] The free-radical (unpaired electron) containing active-site of enzyme Ribonucleotide Reductase, RnR—which controls the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of DNA—can be disabled by a stream of passing electrons.

Modern use

Although a 1999 meta-analysis found that electrotherapy could speed the healing of wounds,[9] in 2000 the Dutch Medical Council found that although it was widely used, there was insufficient evidence for its benefits.[10] Since that time, a few publications have emerged that seem to support its efficacy, but data is still scarce.[11]

The use of electrotherapy has been researched and accepted in the field of rehabilitation[12] (electrical muscle stimulation). The American Physical Therapy Association acknowledges the use of electrotherapy for:[13]

- Improves range of joint movement

2. Treatment of neuromuscular dysfunction

- Improvement of strength

- Improvement of motor control

- Retards muscle atrophy

- Improvement of local blood flow

3. Improves range of joint mobility

- Induces repeated stretching of contracted, shortened soft tissues

4. Tissue repair

- Enhances microcirculation and protein synthesis to heal wounds

- Increased blood flow to the injured tissues increases macrophages to clean up debri

- Restores integrity of connective and dermal tissues

5. Acute and chronic edema

- Accelerates absorption rate

- Affects blood vessel permeability

- Increases mobility of proteins, blood cells and lymphatic flow

6. Peripheral blood flow

- Induces arterial, venous and lymphatic flow

- Delivery of pharmacological agents

- DC (direct current) transports ions through skin

- Common drugs used:

- Dexamethasone

- Acetic acid

- Lidocaine

8. Urine and fecal incontinence

- Affects pelvic floor musculature to reduce pelvic pain and strengthen musculature

- Treatment may lead to complete continence

9. Lymphatic Drainage

- Stimulate lymphatic system to reduce edema

Electrotherapy is primarily used in physical therapy for relaxation of muscle spasms, prevention and retardation of disuse atrophy, increase of local blood circulation, muscle rehabilitation and re-education electrical muscle stimulation, maintaining and increasing range of motion, management of chronic and intractable pain, post-traumatic acute pain, post surgical acute pain, immediate post-surgical stimulation of muscles to prevent venous thrombosis, wound healing and drug delivery.

Some of the treatment effectiveness mechanisms are little understood, with effectiveness and best practices for their use still anecdotal.

Electrotherapy devices have been studied in the treatment of chronic wounds and pressure ulcers. A 1999 meta-analysis of published trials found some evidence that electrotherapy could speed the healing of such wounds, though it was unclear which devices were most effective and which types of wounds were most likely to benefit.[9] However, a more detailed review by the Cochrane Library found no evidence that electromagnetic therapy, a subset of electrotherapy, was effective in healing pressure ulcers[14] or venous stasis ulcers.[15]

Versus manual therapy

Current research displays that manual therapy is more effective than electrotherapy in the treatment and rehabilitation of orthopedic injuries; with improved pain modulation, improved range of motion and physical function, and communication between patient and clinician. Manual therapy is significantly more effective treating pain, stiffness, and physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis than electrotherapy.[16] An up-and-coming manual therapy technique called positional-release therapy (PRT) addresses the damaged muscle fibers and puts them in a position to be able to return to normal efficient function.[17] Contrast to PRT many electrotherapy treatments, such as a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), do not provide any long term changes to the tissue it only addresses the acute pain. Despite the fact that the research states manual therapy is ideal and overall more effective, there are numerous variables involved in determining success rates for treatments.

See also

- Alfred Charles Garratt

- Cranial electrotherapy stimulation

- Deep brain stimulation

- Electrical brain stimulation

- Electrical muscle stimulation

- Electroanalgesia

- Electroconvulsive therapy

- Electrotherapy (cosmetic)

- Galvanic bath

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation

References

- ↑ Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, "The IEEE standard dictionary of electrical and electronics terms". 6th ed. New York, N.Y., Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, c1997. IEEE Std 100-1996. ISBN 1-55937-833-6 [ed. Standards Coordinating Committee 10, Terms and Definitions; Jane Radatz, (chair)]

- ↑ Mollon B, da Silva V, Busse JW, Einhorn TA, Bhandari M (November 2008). "Electrical stimulation for long-bone fracture-healing: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 90 (11): 2322–30. PMID 18978400. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00111.

- ↑ Steavenson, William Edward (1892). Medical electricity. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston, Son & Company. p. 3.

- ↑ Licht, Sidney Herman., "History of Electrotherapy", in Therapeutic Electricity and Ultraviolet Radiation, 2nd ed., ed. Sidney Licht, New Haven: E. Licht, 1967, Pp. 1-70.

- ↑ Licht, "History of Electrotherapy"

- ↑ Humphrey, C.E.; Seal, E.H. (1959). "Biophysical approach toward tumor regression in mice". Science. 130: 388–390. doi:10.1126/science.130.3372.388.

- ↑ David, S.L; Absolom, D.R.; Smith, C.R.; Gams, J.; Herbert, M.A. (1985). "Effect of low level direct current on in vivo tumor growth in hamsters". Cancer Research. 45: 5625–5631.

- ↑ Kulsh, J. (1997). "Targeting a key enzyme in cell growth: a novel therapy for cancer". Medical Hypotheses. 49: 297–300. doi:10.1016/s0306-9877(97)90193-6.

- 1 2 Gardner SE, Frantz RA, Schmidt FL (1999). "Effect of electrical stimulation on chronic wound healing: a meta-analysis". Wound Repair Regen. 7 (6): 495–503. PMID 10633009. doi:10.1046/j.1524-475X.1999.00495.x.

- ↑ Bouter LM (March 2000). "[Insufficient scientific evidence for efficacy of widely used electrotherapy, laser therapy, and ultrasound treatment in physiotherapy]". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd (in Dutch and Flemish). 144 (11): 502–5. PMID 10735134.

- ↑ Nicolakis P, et al. (August 2002). "Pulsed magnetic field therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee--a double-blind sham-controlled trial". Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 114: 678–84. PMID 12602111.

- ↑ Robinson AJ, Snyder-Mackler, L. Clinical electrophysiology: electrotherapy and electrophysiologic testing 3rd ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2008;151-196, 198-237, 239-274

- ↑ Alon G et al. Electrotherapeutic Terminology in Physical Therapy; Section on Clinical Electrophysiology. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association, 2005

- ↑ Aziz Z, Flemming K (2015). "Electromagnetic therapy for treating pressure ulcers". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 9: CD002930. PMID 26334539. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002930.pub6.

- ↑ Aziz Z, Cullum N, Flemming K (2015). "Electromagnetic therapy for treating venous leg ulcers". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7: CD002933. PMID 26134172. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002933.pub6.

- ↑ Ali, S. S., Ahmed, S. I., Khan, M., & Soomro, R. R. (2014). Comparing the effects of manual therapy versus electrophysical agents in the management of knee osteoarthritis. Pakistan Journal Of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 27, 1103-1106. Retrieved from http://www.pjps.pk

- ↑ Speicher, T., & Draper, D. (2006, September 1). Top 10 Positional-Release Therapy Techniques to Break the Chain of Pain. Athletic Therapy Today, 56-62. Retrieved from https://mymasonportal.gmu.edu/bbcswebdav/pid-5287265-dt-content-rid-77501707_1/courses/78587.201570/PRT%20article.pdf

Further reading

- Singh, Jagmohan; "Textbook of Electrotherapy", Ed.1/2005, ISBN 81-8061-384-4; Pub: JAYPEE Brothers Medical Publishers, New Delhi; Cover type: Paperback

- Nelson, Roger M.; Currier, Dean P.; "Clinical Electrotherapy"; 2nd ed., ISBN 0-8385-1334-4; 422 p. Appleton & Lange, a publishing division of Prentice Hall, c1991 c1987; 3rd ed., ISBN 0-8385-1491-X;

- Becker, Robert O.; "The Body Electric. Electromagnetism and the Foundation of Life" (with Gary Selden). Morrow, New York 1985, ISBN 0-688-06971-1

- Becker, Robert O.; "Cross Currents. The Promise of Electromedicine, the Perils of Electropollution" Torcher, Los Angeles 1990, ISBN 0-87477-536-1

- Watkins, Arthur Lancaster, "A manual of electrotherapy.". 2d ed., thoroughly rev. Philadelphia : Lea & Febiger, c1962. 272 p.

- Scott, Bryan O., "The principles and practice of electrotherapy and actinotherapy". Springfield, Ill., C.C. Thomas, c1959. 314 p. LCCN 60004533 /L

- Neuroelectric Conference (1969 : San Francisco, Calif.), " Neuroelectric research; electroneuroprosthesis, electroanesthesia and nonconvulsive electrotherapy". Editor, David V. Reynolds and Anita E. Sjoberg. Springfield, Ill., Thomas, 1971. LCCN 75115389 (ed. Selected papers presented at the 1969 Neuroelectric Conference, the second annual conference of the Neuroelectric Society.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Electrotherapy. |

- Electrotherapy on the Web Tim Watson's website on electrotherapy, containing in-depth discussion and dose calculations.

- The Turn of The Century Electrotherapy Museum

- Atlas of electrotherapy (PDF)