Integer triangle

An integer triangle or integral triangle is a triangle all of whose sides have lengths that are integers. A rational triangle can be defined as one having all sides with rational length; any such rational triangle can be integrally rescaled (can have all sides multiplied by the same integer, namely a common multiple of their denominators) to obtain an integer triangle, so there is no substantive difference between integer triangles and rational triangles in this sense. Note however, that other definitions of the term "rational triangle" also exist: In 1914 Carmichael[1] used the term in the sense that we today use the term Heronian triangle; Somos[2] uses it to refer to triangles whose ratios of sides are rational; Conway and Guy [3] define a rational triangle as one with rational sides and rational angles measured in degrees—in which case the only rational triangle is the rational-sided equilateral triangle.

There are various general properties for an integer triangle, given in the first section below. All other sections refer to classes of integer triangles with specific properties.

General properties for an integer triangle

Integer triangles with given perimeter

Any triple of positive integers can serve as the side lengths of an integer triangle as long as it satisfies the triangle inequality: the longest side is shorter than the sum of the other two sides. Each such triple defines an integer triangle that is unique up to congruence. So the number of integer triangles (up to congruence) with perimeter p is the number of partitions of p into three positive parts that satisfy the triangle inequality. This is the integer closest to p2⁄48 when p is even and to (p + 3)2⁄48 when p is odd.[4][5] It also means that the number of integer triangles with even numbered perimeters p = 2n is the same as the number of integer triangles with odd numbered perimeters p = 2n − 3. Thus there is no integer triangle with perimeter 1, 2 or 4, one with perimeter 3, 5, 6 or 8, and two with perimeter 7 or 10. The sequence of the number of integer triangles with perimeter p, starting at p = 1, is:

Integer triangles with given largest side

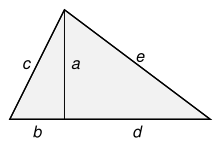

The number of integer triangles (up to congruence) with given largest side c and integer triple (a, b, c) is the number of integer triples such that a + b > c and a ≤ b ≤ c. This is the integer value Ceiling[ (c + 1)⁄2] * Floor[ (c + 1)⁄2].[4] Alternatively, for c even it is the double triangular number c⁄2( c⁄2 + 1) and for c odd it is the square (c + 1)2⁄4. It also means that the number of integer triangles with greatest side c exceeds the number of integer triangles with greatest side c−2 by c. The sequence of the number of non-congruent integer triangles with largest side c, starting at c = 1, is:

- 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 16, 20, 25, 30, 36, 42, 49, 56, 64, 72, 81, 90 ... (sequence A002620 in the OEIS)

The number of integer triangles (up to congruence) with given largest side c and integer triple (a, b, c) that lie on or within a semicircle of diameter c is the number of integer triples such that a + b > c , a2 + b2 ≤ c2 and a ≤ b ≤ c. This is also the number of integer sided obtuse or right (non-acute) triangles with largest side c. The sequence starting at c = 1, is:

- 0, 0, 1, 1, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, 13, 15, 17, 22, 25, 30, 33, 38, 42, 48 ... (sequence A236384 in the OEIS)

Consequently, the difference between the two above sequences gives the number of acute integer sided triangles (up to congruence) with given largest side c. The sequence starting at c = 1, is:

- 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 11, 13, 15, 17, 21, 25, 27, 31, 34, 39, 43, 48, 52 ... (sequence A247588 in the OEIS)

Area of an integer triangle

By Heron's formula, if T is the area of a triangle whose sides have lengths a, b, and c then

Since all the terms under the radical on the right side of the formula are integers it follows that all integer triangles must have an integer value of 16T2 and T2 will be rational.

Angles of an integer triangle

By the law of cosines, every angle of an integer triangle has a rational cosine.

If the angles of any triangle form an arithmetic progression then one of its angles must be 60°.[6] For integer triangles the remaining angles must also have rational cosines and a method of generating such triangles is given below. However, apart from the trivial case of an equilateral triangle there are no integer triangles whose angles form either a geometric or harmonic progression. This is because such angles have to be rational angles of the form πp⁄q with rational 0 < p⁄q < 1. But all the angles of integer triangles must have rational cosines and this will occur only when p⁄q = 1⁄3 [7]:p.2 i.e. the integer triangle is equilateral.

The square of each internal angle bisector of an integer triangle is rational, because the general triangle formula for the internal angle bisector of angle A is where s is the semiperimeter (and likewise for the other angles' bisectors).

Side split by an altitude

Any altitude dropped from a vertex onto an opposite side or its extension will split that side or its extension into rational lengths.

Medians

The square of twice any median of an integer triangle is an integer, because the general formula for the squared median ma2 to side a is , giving (2ma)2 = 2b2 + 2c2 − a2 (and likewise for the medians to the other sides).

Circumradius and inradius

Because the square of the area of an integer triangle is rational, the square of its circumradius is also rational, as is the square of the inradius.

The ratio of the inradius to the circumradius of an integer triangle is rational, equaling for semiperimeter s and area T.

The product of the inradius and the circumradius of an integer triangle is rational, equaling

Thus the squared distance between the incenter and the circumcenter of an integer triangle, given by Euler's theorem as R2−2Rr, is rational.

Heronian triangles

General formula

A Heronian triangle, also known as a Heron triangle or a Hero triangle, is a triangle with integer sides and integer area. Every Heronian triangle has sides proportional to[8]

for integers m, n and k subject to the constraints:

- .

The proportionality factor is generally a rational where reduces the generated Heronian triangle to its primitive and scales up this primitive to the required size.

Pythagorean triangles

A Pythagorean triangle is right angled and Heronian. Its three integer sides are known as a Pythagorean triple or Pythagorean triplet or Pythagorean triad.[9] All Pythagorean triples with hypotenuse which are primitive (the sides having no common factor) can be generated by

where m and n are coprime integers and one of them is even with m > n.

Every even number greater than 2 can be the leg of a Pythagorean triangle (not necessarily primitive) because if the leg is given by and we choose as the other leg then the hypotenuse is .[10] This is essentially the generation formula above with set to 1 and allowing to range from 2 to infinity.

Pythagorean triangles with integer altitude from the hypotenuse

There are no primitive Pythagorean triangles with integer altitude from the hypotenuse. This is because twice the area equals any base times the corresponding height: 2 times the area thus equals both ab and cd where d is the height from the hypotenuse c. The three side lengths of a primitive triangle are coprime, so d = ab⁄c is in fully reduced form; since c cannot equal 1 for any primitive Pythagorean triangle, d cannot be an integer.

However, if we have a non-primitive Pythagorean triple (ka, kb, kc), where (a, b, c) is a primitive Pythagorean triple and k a positive integer, then we see that d = kab⁄c, so we have an integer altitude iff c | k. Such a triangle is called decomposable, as dividing it into two similar smaller triangles with that altitude yields two more Pythagorean triangles. This is because in each smaller triangle generated, the altitude of the main triangle corresponds to one of the legs of the main triangle under the rescaling, but it is an integer multiple of that leg's value in the primitive triangle, as can be seen from the equation for the altitude above, so this is our scale factor from the primitive triangle to this subtriangle. Thus, in short, each subtriangle is the result of scaling our primitive triangle by some positive integer scale factor and thus is still a Pythagorean triangle. Unfortunately, these triangles are not in general decomposable themselves, so we don't get any fractal-type pattern.

A simple example is the Pythagorean triangle corresponding to (15, 20, 25). This has d = 12 an integer, because it is expressible as (5*3, 5*4, 5*5), so k = 5 and (a, b, c) = (3, 4, 5). And indeed, we have that our scale factor 5 is a multiple of our primitive hypotenuse 5. This is actually the smallest example possible.

Furthermore, any Pythagorean triangle with legs x, y and hypotenuse z can generate a Pythagorean triangle with an integer altitude, by scaling up the sides by the length of the hypotenuse z. If d is the altitude, then the generated Pythagorean triangle with integer altitude is given by[11]

Consequently, all Pythagorean triangles with legs a and b, hypotenuse c, and integer altitude d from the hypotenuse, with gcd (a, b, c, d) = 1, which necessarily have both a2 + b2 = c2 and , are generated by[12][11]

for coprime integers m, n with m > n.

Heronian triangles with sides in arithmetic progression

A triangle with integer sides and integer area has sides in arithmetic progression if and only if[13] the sides are (b – d, b, b + d), where

and where g is the greatest common divisor of , and

Heronian triangles with one angle equal to twice another

All Heronian triangles with B=2A are generated by[14] either

with integers k, s, r such that s2 > 3r2, or

- ,

- ,

- ,

- ,

with integers q, u, v such that v > u and v2 < (7+4√3)u2.

No Heronian triangles with B = 2A are isosceles or right triangles because all resulting angle combinations generate angles with non-rational sines, giving a non-rational area or side.

Isosceles Heronian triangles

All isosceles Heronian triangles are given by rational multiples of[15]

for coprime integers u and v with u>v.

Heronian triangles whose perimeter is four times a prime

It has been shown that a Heronian triangle whose perimeter is four times a prime is uniquely associated with the prime and that the prime is of the form . [16][17] It is well known that such a prime can be uniquely partitioned into integers and such that (see Euler's idoneal numbers). Furthermore, it has been shown that such Heronian triangles are primitive since the smallest side of the triangle has to be equal to the prime that is one quarter of its perimeter.

Consequently, all primitive Heronian triangles whose perimeter is four times a prime can be generated by

for integers and such that is a prime.

Furthermore, the factorization of the area is where is prime. However the area of a Heronian triangle is always divisible by . This gives the result that apart from when and which gives all other parings of and must have odd with only one of them divisible by .

Heronian triangles as faces of a tetrahedron

There exist tetrahedra having integer-valued volume and Heron triangles as faces. One example has one edge of 896, the opposite edge of 190, and the other four edges of 1073; two faces have areas of 436800 and the other two have areas of 47120, while the volume is 62092800.[18]:p.107

Properties of Heronian triangles

- The perimeter of a Heronian triangle is always an even number.[19] Thus every Heronian triangle has an odd number of sides of even length,[20]:p.3 and every primitive Heronian triangle has exactly one even side.

- The semiperimeter s of a Heronian triangle with sides a, b and c can never be prime. This can be seen from the fact that s(s−a)(s−b)(s−c) has to be a perfect square and if s is a prime then one of the other terms must have s as a factor but this is impossible as these terms are all less than s.

- The area of a Heronian triangle is always divisible by 6.[19]

- All the altitudes of a Heronian triangle are rational.[2] This can be seen from the fact that the area of a triangle is half of one side times its altitude from that side, and a Heronian triangle has integer sides and area. Some Heronian triangles have three non-integer altitudes, for example the acute (15, 34, 35) with area 252 and the obtuse (5, 29, 30) with area 72. Any Heronian triangle with one or more non-integer altitudes can be scaled up by a factor equalling the least common multiple of the altitudes' denominators in order to obtain a similar Heronian triangle with three integer altitudes.

- Heronian triangles that have no integer altitude (in-decomposable and non-Pythagorean) have sides that are all divisible by primes of the form 4k+1.[21]:p.40 However decomposable Heronian triangles must have two sides that are the hypotenuse of Pythagorean triangles. Hence all Heronian triangles that are not Pythagorean have at least two sides that are divisible by primes of the form 4k+1. Finally all Heronian triangles have at least one side that is divisible by primes of the form 4k+1.

- All the interior perpendicular bisectors of a Heronian triangle are rational: For any triangle these are given by and where the sides are a ≥ b ≥ c and the area is T;[22] in a Heronian triangle all of a, b, c, and T are integers.

- There are no equilateral Heronian triangles.[2]

- There are no Heronian triangles with a side length of either 1 or 2.[23]

- There exist an infinite number of primitive Heronian triangles with one side length equal to a provided that a > 2.[23]

- There are no Heronian triangles whose side lengths form a geometric progression.[13]

- If any two sides (but not three) of a Heronian triangle have a common factor, that factor must be the sum of two squares.[24]

- Every angle of a Heronian triangle has a rational sine. This follows from the area formula Area = (1/2)ab sin C, in which the area and the sides a and b are integers (and equivalently for the other angles). Since all integer triangles have all angles' cosines rational, this implies that each oblique angle of a Heron triangle has a rational tangent.

- There are no Heronian triangles whose three internal angles form an arithmetic progression. This is because at least one angle has to be 60°, which does not have a rational sine.[6]

- Any square inscribed in a Heronian triangle has rational sides: For a general triangle the inscribed square on side of length a has length where T is the triangle's area;[25] in a Heronian triangle, both T and a are integers.

- Every Heronian triangle has a rational inradius (radius of its inscribed circle): For a general triangle the inradius is the ratio of the area to half the perimeter, and both of these are rational in a Heronian triangle.

- Every Heronian triangle has a rational circumradius (the radius of its circumscribed circle): For a general triangle the circumradius equals one-fourth the product of the sides divided by the area; in a Heronian triangle the sides and area are integers.

- In a Heronian triangle the distance from the centroid to each side is rational, because for all triangles this distance is the ratio of twice the area to three times the side length.[26] This can be generalized by stating that all centers associated with Heronian triangles whose barycentric coordinates are rational ratios have a rational distance to each side. These centers include the circumcenter, orthocenter, nine-point center, symmedian point, Gergonne point and Nagel point.[27]

Integer automedian triangles

An automedian triangle is one whose medians are in the same proportions (in the opposite order) as the sides. If x, y, and z are the three sides of a right triangle, sorted in increasing order by size, and if 2x < z, then z, x + y, and y − x are the three sides of an automedian triangle. For instance, the right triangle with side lengths 5, 12, and 13 can be used in this way to form the smallest integer automedian triangle, with side lengths 13, 17, and 7.[28]

Consequently, using Euclid's formula, which generates primitive Pythagorean triangles, it is possible to generate primitive integer automedian triangles as

with and coprime and odd, and or to satisfy the triangle inequality.

Integer triangles in a 2D lattice

A 2D lattice is a regular array of isolated points where if any one point is chosen as the Cartesian origin (0, 0), then all the other points are at (x, y) where x and y range over all positive and negative integers. A lattice triangle is any triangle drawn within a 2D lattice such that all vertices lie on lattice points. By Pick's theorem a lattice triangle has a rational area that either is an integer or has a denominator of 2. If the lattice triangle has integer sides then it is Heronian with integer area.[20]

Furthermore, it has been proved that all Heronian triangles can be drawn as lattice triangles.[29][30] Consequently, it can be stated that an integer triangle is Heronian if and only if it can be drawn as a lattice triangle.

Integer triangles with specific angle properties

Integer triangles with a rational angle bisector

A triangle family with integer sides and with rational bisector of angle A is given by[31]

with integers .

Integer triangles with integer n-sectors of all angles

There exist infinitely many non-similar triangles in which the three sides and the bisectors of each of the three angles are integers.[32]

There exist infinitely many non-similar triangles in which the three sides and the two trisectors of each of the three angles are integers.[32]

However, for n > 3 there exist no triangles in which the three sides and the (n–1) n-sectors of each of the three angles are integers.[32]

Integer triangles with one angle with a given rational cosine

Some integer triangles with one angle at vertex A having given rational cosine h/k (h<0 or >0; k>0) are given by[33]

where p and q are any coprime positive integers such that p>qk.

Integer triangles with a 60° angle (angles in arithmetic progression)

All integer triangles with a 60° angle have their angles in an arithmetic progression. All such triangles are proportional to:[6]

with coprime integers m, n and 1 ≤ n ≤ m or 3m ≤ n. From here, all primitive solutions can be obtained by dividing a, b, and c by their greatest common divisor.

Integer triangles with a 60° angle can also be generated by[34]

with coprime integers m, n with 0 < n < m (the angle of 60° is opposite to the side of length a). From here, all primitive solutions can be obtained by dividing a, b, and c by their greatest common divisor (e.g. an equilateral triangle solution is obtained by taking m = 2 and n = 1, but this produces a = b = c = 3, which is not a primitive solution). See also [35][36]

More precisely, If , then , otherwise . Two different pairs and generate the same triple. Unfortunately the two pairs can both be of gcd=3, so we can't avoid duplicates by simply skipping that case. Instead, duplicates can be avoided by going only till . Note that we still need to divide by 3 if gcd=3. The only solution for under the above constraints is for . With this additional constraint all triples can be generated uniquely.

An Eisenstein triple is a set of integers which are the lengths of the sides of a triangle where one of the angles is 60 degrees.

Integer triangles with a 120° angle

Integer triangles with a 120° angle can be generated by[37]

with coprime integers m, n with 0 < n < m (the angle of 120° is opposite to the side of length a). From here, all primitive solutions can be obtained by dividing a, b, and c by their greatest common divisor (e.g. by taking m = 4 and n = 1, one obtains a = 21, b = 9 and c = 15, which is not a primitive solution, but leads to the primitive solution a = 7, b = 3, and c = 5 which, up to order, can be obtained with the values m = 2 and n = 1). See also.[35][36]

More precisely, If , then , otherwise . Since the biggest side a can only be generated with a single pair, each primitive triple can be generated in precisely two ways: once directly with gcd=1, and once indirectly with gcd=3. Therefore, in order to generate all primitive triples uniquely, one can just add additional condition.

Integer triangles with one angle equal to an arbitrary rational number times another angle

For positive relatively prime integers h and k, the triangle with the following sides has angles , , and and hence two angles in the ratio h : k, and its sides are integers:[38]

where and p and q are any relatively prime integers such that .

Integer triangles with one angle equal to twice another

With angle A opposite side and angle B opposite side , some triangles with B=2A are generated by[39]

with integers m, n such that 0 < n < m < 2n.

Note that all triangles with B = 2A (whether integer or not) have[40] .

Integer triangles with one angle equal to 3/2 times another

The equivalence class of similar triangles with are generated by[39]

with integers such that , where is the golden ratio .

Note that all triangles with (whether with integer sides or not) satisfy .

Integer triangles with one angle three times another

We can generate the full equivalence class of similar triangles that satisfy B=3A by using the formulas [41]

where and are integers such that .

Note that all triangles with B = 3A (whether with integer sides or not) satisfy .

Integer triangles with integer ratio of circumradius to inradius

Conditions are known in terms of elliptic curves for an integer triangle to have an integer ratio N of the circumradius to the inradius.[42][43] The smallest case, that of the equilateral triangle, has N=2. In every known case, N ≡ 2 (mod 8)—that is, N–2 is divisible by 8.

5-Con triangle pairs

A 5-Con triangle pair is a pair of triangles that are similar but not congruent and that share three angles and two sidelengths. Primitive integer 5-Con triangles, in which the four distinct integer sides (two sides each appearing in both triangles, and one other side in each triangle) share no prime factor, have triples of sides and for positive coprime integers x and y. The smallest example is the pair (8, 12, 18), (12, 18, 27), generated by x = 2, y = 3.

Particular integer triangles

- The only triangle with consecutive integers for sides and area has sides (3, 4, 5) and area 6.

- The only triangle with consecutive integers for an altitude and the sides has sides (13, 14, 15) and altitude from side 14 equal to 12.

- The (2, 3, 4) triangle and its multiples are the only triangles with integer sides in arithmetic progression and having the complementary exterior angle property.[44][45][46] This property states that if angle C is obtuse and if a segment is dropped from B meeting perpendicularly AC extended at P, then ∠CAB=2∠CBP.

- The (3, 4, 5) triangle and its multiples are the only integer right triangles having sides in arithmetic progression[46]

- The (4, 5, 6) triangle and its multiples are the only triangles with one angle being twice another and having integer sides in arithmetic progression.[46]

- The (3, 5, 7) triangle and its multiples are the only triangles with a 120° angle and having integer sides in arithmetic progression.[46]

- The only integer triangle with area=semiperimeter[47] has sides (3, 4, 5).

- The only integer triangles with area = perimeter have sides[47][48] (5, 12, 13), (6, 8, 10), (6, 25, 29), (7, 15, 20), and (9, 10, 17). Of these the first two, but not the last three, are right triangles.

- There exist integer triangles with three rational medians.[9]:p. 64 The smallest has sides (68, 85, 87). Others include (127, 131, 158), (113, 243, 290), (145, 207, 328) and (327, 386, 409).

- There are no isosceles Pythagorean triangles.[15]

- The only primitive Pythagorean triangles for which the square of the perimeter equals an integer multiple of the area are (3, 4, 5) with perimeter 12 and area 6 and with the ratio of perimeter squared to area being 24; (5, 12, 13) with perimeter 30 and area 30 and with the ratio of perimeter squared to area being 30; and (9, 40, 41) with perimeter 90 and area 180 and with the ratio of perimeter squared to area being 45.[49]

See also

- Robbins pentagon, a cyclic pentagon with integer sides and integer area

- Euler brick, a cuboid with integer edges and integer face diagonals

- Tetrahedron#Integer tetrahedra

References

- ↑ Carmichael, R. D. (1959) [1914]. "Diophantine Analysis". In R. D. Carmichael. The Theory of Numbers and Diophantine Analysis. Dover. pp. 11–13.

- 1 2 3 Somos, M., "Rational triangles", http://somos.crg4.com/rattri.html

- ↑ Conway, J. H., and Guy, R. K., "The only rational triangle", in The Book of Numbers, 1996, Springer-Verlag, pp. 201 and 228–239.

- 1 2 Tom Jenkyns and Eric Muller, Triangular Triples from Ceilings to Floors, American Mathematical Monthly 107:7 (August 2000) 634–639

- ↑ Ross Honsberger, Mathematical Gems III, pp. 39–37

- 1 2 3 Zelator, K., "Triangle Angles and Sides in Progression and the diophantine equation x2+3y2=z2", Cornell Univ. archive, 2008

- ↑ Jahnel, Jörg (2010). "When is the (Co)Sine of a Rational Angle equal to a rational number?". arXiv:1006.2938

.

. - ↑ Carmichael, R. D. The Theory of Numbers and Diophantine Analysis. New York: Dover, 1952.

- 1 2 Sierpiński, Wacław. Pythagorean Triangles, Dover Publ., 2003 (orig. 1962).

- ↑ "Sloane's A009111 (see the comment from Mar 02 2017)". The On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. OEIS Foundation. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- 1 2 Richinick, Jennifer, "The upside-down Pythagorean Theorem", Mathematical Gazette 92, July 2008, 313–317.

- ↑ Voles, Roger, "Integer solutions of a−2+b−2=d−2", Mathematical Gazette 83, July 1999, 269–271.

- 1 2 Buchholz, R. H.; MacDougall, J. A. (1999). "Heron Quadrilaterals with sides in Arithmetic or Geometric progression". Bulletin of the Australian Mathematical Society. 59: 263–269.

- ↑ Mitchell, Douglas W., "Heron triangles with ∠B=2∠A", Mathematical Gazette 91, July 2007, 326–328.

- 1 2 Sastry, K. R. S., "Construction of Brahmagupta n-gons", Forum Geometricorum 5 (2005): 119–126.

- ↑ Yiu, P., "CRUX, Problem 2331, Proposed by Paul Yiu", Memorial University of Newfoundland (1998): 175-177

- ↑ Yui, P. and Taylor, J. S., "CRUX, Problem 2331, Solution" Memorial University of Newfoundland (1999): 185-186

- ↑ Wacław Sierpiński, Pythagorean Triangles, Dover Publications, 2003 (orig. ed. 1962).

- 1 2 Friche, Jan (2 January 2002). "On Heron Simplices and Integer Embedding" (PDF). Ernst-Moritz-Arndt Universät Greiswald Publication.

- 1 2 Buchholz, R. H.; MacDougall, J. A. (2001). "Cyclic Polygons with Rational Sides and Area". CiteSeerX Penn State University: 3. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.169.6336

.

. - ↑ Yiu, Paul (2008). "Heron triangles which cannot be decomposed into two integer right triangles" (PDF). 41st Meeting of Florida Section of Mathematical Association of America.

- ↑ Mitchell, Douglas W. (2013), "Perpendicular Bisectors of Triangle Sides", Forum Geometricorum 13, 53−59: Theorem 2.

- 1 2 Carlson, John R. (1970). "Determination of Heronian triangles" (PDF). San Diego State College.

- ↑ Blichfeldt, H. F. (1896–1897). "On Triangles with Rational Sides and Having Rational Areas". Annals of Mathematics. 11 (1/6): 57–60. JSTOR 1967214. doi:10.2307/1967214.

- ↑ Bailey, Herbert, and DeTemple, Duane, "Squares inscribed in angles and triangles", Mathematics Magazine 71(4), 1998, 278–284.

- ↑ Clark Kimberling, "Trilinear distance inequalities for the symmedian point, the centroid, and other triangle centers", Forum Geometricorum, 10 (2010), 135−139. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2010volume10/FG201015index.html

- ↑ Clark Kimberling's Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-19. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

- ↑ Parry, C. F. (1991). "Steiner–Lehmus and the automedian triangle". The Mathematical Gazette. 75 (472): 151–154. JSTOR 3620241..

- ↑ P. Yiu, "Heronian triangles are lattice triangles", American Mathematical Monthly 108 (2001), 261–263.

- ↑ Marshall, Susan H.; Perlis, Alexander R. (2012). "Heronian tetrahedra are lattice tetrahedra" (PDF). University of Arizona: 2.

- ↑ Zelator, Konstantine, Mathematical Spectrum 39(3), 2006/2007, 59−62.

- 1 2 3 De Bruyn,Bart, "On a Problem Regarding the n-Sectors of a Triangle", Forum Geometricorum 5, 2005: pp. 47–52.

- ↑ Sastry, K. R. S., "Integer-sided triangles containing a given rational cosine", Mathematical Gazette 68, December 1984, 289−290.

- ↑ Gilder, J., Integer-sided triangles with an angle of 60°", Mathematical Gazette 66, December 1982, 261 266

- 1 2 Burn, Bob, "Triangles with a 60° angle and sides of integer length", Mathematical Gazette 87, March 2003, 148–153.

- 1 2 Read, Emrys, "On integer-sided triangles containing angles of 120° or 60°", Mathematical Gazette 90, July 2006, 299−305.

- ↑ Selkirk, K., "Integer-sided triangles with an angle of 120°", Mathematical Gazette 67, December 1983, 251–255.

- ↑ Hirschhorn, Michael D., "Commensurable triangles", Mathematical Gazette 95, March 2011, pp. 61−63.

- 1 2 Deshpande,M. N., "Some new triples of integers and associated triangles", Mathematical Gazette 86, November 2002, 464–466.

- ↑ Willson, William Wynne, "A generalisation of the property of the 4, 5, 6 triangle", Mathematical Gazette 60, June 1976, 130–131.

- ↑ Parris, Richard (November 2007). College Mathematics Journal. 38 (5): 345–355. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ MacLeod, Allan J., "Integer triangles with R/r = N", Forum Geometricorum 10, 2010: pp. 149−155.

- ↑ Goehl, John F. Jr., "More integer triangles with R/r = N", Forum Geometricorum 12, 2012: pp. 27−28

- ↑ Barnard, T., and Silvester, J., "Circle theorems and a property of the (2,3,4) triangle", Mathematical Gazette 85, July 2001, 312−316.

- ↑ Lord, N., "A striking property of the (2,3,4) triangle", Mathematical Gazette 82, March 1998, 93−94.

- 1 2 3 4 Mitchell, Douglas W., "The 2:3:4, 3:4:5, 4:5:6, and 3:5:7 triangles", Mathematical Gazette 92, July 2008.

- 1 2 MacHale, D., "That 3,4,5 triangle again", Mathematical Gazette 73, March 1989, 14−16.

- ↑ L. E. Dickson, History of the Theory of Numbers, vol.2, 181.

- ↑ Goehl, John F. Jr., "Pythagorean triangles with square of perimeter equal to an integer multiple of area", Forum Geometricorum 9 (2009): 281–282.