Insular illumination

Insular illumination refers to the production of illuminated manuscripts in the monasteries of Ireland and Great Britain between the 6th and 9th centuries, as well as in monasteries under their influence on continental Europe. It is characterised by decoration strongly influenced by metalwork, the constant use of interlacing, and the importance assigned to calligraphy. The most celebrated books of this sort are largely gospel books. Around sixty manuscripts are known from this period.

History

The insular artistic style began after the conversion of Ireland by St Patrick in the 4th and 5th centuries AD. The new religious institutions of Celtic Christianity, mostly organised around monasteries, ordered the creation of numerous works of art, liturgical objects and vestments, and also manuscripts. Two types of manuscripts dominated: small format gospels to be used by preachers and missionaries or in private worship (e.g. the Book of Dimma and the Book of Mulling), and large works, reserved for the liturgical services of the monasteries (such as the Book of Kells).[1]

The Irish monks took part in the conversion of Scotland and the north of Great Britain], establishing numerous monasteries, such as Iona Abbey, founded by Columba in Scotland in 563 and Lindisfarne, founded by Aidan in Northumbria in 635. The Irish missionaries brought their art to Britain along with their religion. Over the course of the 6th and 7th centuries, especially after the Gregorian mission, the south of Britain came under the direct influence of continental Christianity, mainly Italian. Some Italian and Byzantine manuscripts came to the island as a result, influencing the development of insular illumination as well.[2] In turn, the major centres of production were concentrated first in Northumbria, then in southern England and Kent over the 7th and 8th centuries. The monasteries in these places benefited from more conditions which were more prosperous than those in Ireland as well as from the protection and patronage of the Anglo-Saxon kings. The scriptoria of Lindisfarne and Iona were the most prolific at the end of the 8th century.[3]

At the end of the 7th century, several Irish missionaries led by Columbanus travelled to the continent and contributed to the creation of several monasteries in France, Switzerland and Northern Italy. Columbanus' disciple, Saint Gall, took part in the foundation of an abbey in Switzerland and St Kilian of Würzburg was active in southern Germany. All these establishments helped to spread the insular calligraphy and decorative techniques to manuscripts produced on the continent in this period.[1] Often referred to as "Franco-Saxon", the manuscripts made in northern France in the Carolingian period also show a direct insular influence.[4]

Characteristics

Despite the great diversity of origins of manuscripts of the insular style, several common characteristics can be identified.

Treatment of the parchment

The treatment of the parchment creates a suede-like appearance, which makes it very receptive to ink and colour. This treatment was applied to both veal-skin and sheep. It enables both calligraphy and ornamentation.[5]

Types of ornamental motifs

The interlace is the best-known motif of insular art. This decoration, however, is not limited to Celtic art of Insular illumination. It is also seen in some Egyptian papyrus, Byzantine and Italian works and some Anglo-Saxon works of art, like those found in the tomb at Sutton Hoo. But the use of this pattern in insular manuscripts is almost systematic from the middle of the 7th century onwards. It can fill out the space around other types of illumination, as well as initials, frames, margins, and carpet pages. Different types of interlace can be identified: simple, double, or triple.[6]

Rectilinear motifs include diamonds, chequerboard patterns, clefs and Greek frets. Round motifs include circles, spirals, and winding helixes.[7]

Zoomorphic motifs generally extend into the interlace: their heads are located at an end and occasionally the rear of the animal reappears at the other end of the interlace. In the earlier manuscripts, their character remains very schematic and it is difficult to identify specific species of animal. From the Lindisfarne Gospels onwards, some kinds of animal begin to appear with more realism, especially dogs and predators, which recall the art of the hunt appreciated by the Anglo-Saxon elite.[8]

Detail from the Book of Kells, showing interlacing and a zoomorphic spiral, f.24

Detail from the Book of Kells, showing interlacing and a zoomorphic spiral, f.24 Detail of the interlacing and zoomorphic decoration of a Chi-Rho in the Book of Kells

Detail of the interlacing and zoomorphic decoration of a Chi-Rho in the Book of Kells Decoration in the form of a cat, from the Lindisfarne Gospels, f.139r

Decoration in the form of a cat, from the Lindisfarne Gospels, f.139r

Initials

The Cathach of St. Columba (beginning of 7th century) is the oldest extant manuscript with initials decorated in the characteristic style of insular illumination: the first letter is incorporated into the text and is followed by other letters whose size decreases until they reach the size of the main text.The initials themselves are decorated with curves, spirals, points and even animal heads. This type of decoration is found in Celtic art from the la Tène period onwards and marks the true beginning of the distinction between insular and late antique manuscripts.[9]

Initial in the Cathach of St. Columba

Initial in the Cathach of St. Columba Detail of an initial in the Echternach Gospels

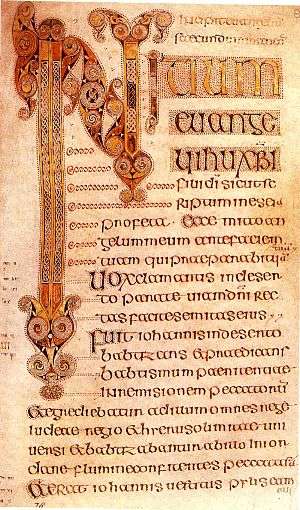

Detail of an initial in the Echternach Gospels Beginning of the Gospel of Mark in the Book of Durrow

Beginning of the Gospel of Mark in the Book of Durrow

Miniatures

The earliest insular designs are generally images of the cross, sometimes included in a carpet page. The first representations of individuals in insular manuscripts probably only occur as a result of the influence of works acquired from the continent. Specialists have been able to distinguish several details of these earliest miniatures which are shared with ancient manuscripts of the Diatessaron from Persia, which might have come to the British Isles as a result of pilgrimage to the Near East. Representations of humans are very schematic, with individuals on foot, usually the Evangelists are represented without wings or nimbus. Sometimes their representation is limited to their symbols (lion, cow, eagle, man) depicted in a heraldic manner.[10]

Cross integrated into a carpet page in the Lindisfarne Gospels

Cross integrated into a carpet page in the Lindisfarne Gospels Portrait of St Luke in the Lichfield Gospels

Portrait of St Luke in the Lichfield Gospels The lion, symbol of St Mark, Echternach Gospels

The lion, symbol of St Mark, Echternach Gospels

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Bernard Meehan, Le Livre de Kells, Thames & Hudson, 1995, ISBN 2878110900, p. 9-10

- ↑ Nordenfalk, p.96–107

- ↑ Nordenfalk, p.25-26

- ↑ "L'école franco-insulaire". Le scriptorium de l'abbaye de Saint-Amand - Bibliothèque de Valencienne. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Nordenfalk, p.14-15

- ↑ Nordenfalk, p.13-14

- ↑ Nordenfalk, p.16

- ↑ Nordenfalk, p.16-17

- ↑ Nordenfalk, p.13

- ↑ Nordenfalk, p.19-20

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Insular manuscripts. |

- Nordenfalk, Carl. Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Painting: Book illumination in the British Isles 600–800. Chatto & Windus, London (New York: George Braziller), 1977.

Further reading

- Alexander, Jonathan J.G. (1978). A survey of manuscripts illuminated in the British Isles: part 1 : Insular manuscripts : 6th to the 9th century. London: Harvey Miller ed. p. 219. ISBN 0905203011.

External links

- L'influence insulaire sur l'enluminure carolingienne on the website of the BNF