Seam (sewing)

In sewing, a seam is the join where two or more layers of fabric, leather, or other materials are held together with stitches. Prior to the invention of the sewing machine, all sewing was done by hand. Seams in modern mass-produced household textiles, sporting goods, and ready-to-wear clothing are sewn by computerized machines, while home shoemaking, dressmaking, quilting, crafts, haute couture and tailoring may use a combination of hand and machine sewing.[1]

In clothing construction, seams are classified by their type (plain, lapped, abutted, or French seams[1]) and position in the finished garment (center back seam, inseam, side seam). Seams are finished with a variety of techniques to prevent raveling of raw fabric edges and to neaten the inside of garments.[2]

Types

All basics seams used in clothing construction are variants on four basic types of seams:[1]

- Plain seams

- French seams

- Flat or abutted seams

- Lapped seams

A plain seam is the most common type of machine-sewn seam. It joins two pieces of fabric together face-to-face by sewing through both pieces, leaving a seam allowance with raw edges inside the work. The seam allowance usually requires some sort of seam finish to prevent raveling.[3]

Either piping or cording may be inserted into a plain seam.

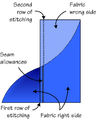

In a French seam, the raw edges of the fabric are fully enclosed for a neat finish. The seam is first sewn with wrong sides together, then the seam allowances are trimmed and pressed. A second seam is sewn with right sides together, enclosing the raw edges of the original seam.[4]

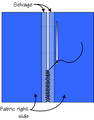

In a flat or abutted seam, two pieces of fabric are joined edge-to edge with no overlap and sewn with hand or machine stitching that encloses the raw edges. Antique or old German seam is the 19th century name for a hand-sewn flat seam that joins two pieces of fabric at their selvages. This type of construction is found in traditional linen garments such as shirts and chemises, and in hand-made sheets pieced from narrow loom widths of linen.[5]

In a lapped seam, the two layers overlap with the wrong side of the top layer laid against the right side of the lower layer. Lapped seams are typically used for bulky materials that do not ravel, such as leather and felt.

Plain seam

Plain seam French seam

French seam Ancient or Old German flat seam

Ancient or Old German flat seam

Finishes

A seam finish is a treatment that secures and neatens the raw edges of a plain seam to prevent raveling,[6] by sewing over the raw edges or enclosing them in some sort of binding.

On mass-produced clothing, the seam allowances of plain seams are usually trimmed and stitched together with an overlock stitch using a serger. Plain seams may also be pressed open, with each seam allowance separately secured with an overlock stitch. Traditional home sewing techniques for finishing plain seams include trimming with pinking shears, oversewing with a zig-zag stitch, and hand or machine overcasting.

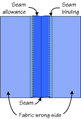

A bound seam has each of the raw edges of its seam allowances enclosed in a strip of fabric, lace or net 'binding' that has been folded in half lengthwise. An example of binding is double-fold bias tape. The binding's fold is wrapped around the raw edge of the seam allowance and is stitched, through all thicknesses, catching underside of binding in stitching.[7]Bound seams are often used on lightweight fabrics including silk and chiffon and on unlined garments to produce a neat finish.

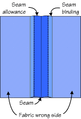

A Hong Kong seam or Hong Kong finish is a home sewing term[8] for a type of bound seam in which each raw edge of the seam allowance is separately encased in a fabric binding. In couture sewing or tailoring, the binding is usually a bias-cut strip of lightweight lining fabric; in home sewing, commercial bias tape is often used.

In a Hong Kong finish, a bias strip of fabric is cut to the width of the seam allowance plus 1/4". The bias strip is placed on top of the seam allowance, right sides together, and stitched 1/8" from raw edges. The bias strip is then folded over the raw edge and around to the underside and stitched in place.

Bound seam – The binding is wrapped around each raw edge and sewn in place with one line of stitching.

Bound seam – The binding is wrapped around each raw edge and sewn in place with one line of stitching. Hong Kong finish

Hong Kong finish

Position

In clothing construction, seams are identified by their position in the finished garment.

A center front seam runs vertically down the front of a garment.

A center back seam or back seam runs vertically down the center-back of a garment. It can be used to create anatomical shaping to the back portion of a garment particularly through the waist area and hips. It can also be used for styling and functional purposes involving pleats, vents, flare toward the hem or for back closures such as buttoned plackets or zippers.

A side seam runs vertically down the side of a garment.

A side-back seam runs from the armscye to the waist, and fits the garment to the curve below the shoulder blades. Side-back seams may be used instead of, or in combination with, side and center back seams.

A shoulder seam runs from the neckline to the armscye, usually at the highest point of the shoulder.

Princess seams in the front or back run from the shoulder or armscye to the hem at the side-back or side-front. Princess seams shape the garment to the body's curves and eliminate the need for darting at the bust, waist, and shoulder.[9]

An inseam is the seam that binds the length of the inner trouser leg. The distance from the bottom crotch to the lower ankle is also known as the inseam. The inseam length determines the length of the inner pant leg to appropriately fit the wearer.[10] In the UK this is usually known as the inside-leg measurement (for trousers fit).

Notching or clipping a curved seam

When making an outward-curved seam, the material will have reduced bulk and lie flat if notches are cut into the seam allowance. Alternatively, when making an inward-curved seam, clips are cut into the seam allowance to help the seam lie flat with reduced bulk in the fabric.[11]

Once seam allowances are pinned or basted, they are often pressed flat with an iron before sewing the final seam. Pressing the seam allowances makes it easier to sew a consistent finished seam.

Clipping done along the seam allowance of an inward-curving seam

Clipping done along the seam allowance of an inward-curving seam Notches cut into the seam allowance of an outward-curved seam

Notches cut into the seam allowance of an outward-curved seam Pressing seam allowances flat with an iron before making final seams – Seams may be basted, tacked or pinned in place before final stitching is done.

Pressing seam allowances flat with an iron before making final seams – Seams may be basted, tacked or pinned in place before final stitching is done.

See also

- Embroidery stitch

- Glossary of sewing terminology

- Glossary of textile manufacturing

- List of sewing stitches

- Notions

Notes

- 1 2 3 Schaeffer (2001), p. 35

- ↑ Readers Digest (1976), pp. 144-158

- ↑ Picken (1957), p. 288

- ↑ Picken (1957), p. 287

- ↑ Dillmont (1884), Chapter 1

- ↑ Readers Digest (1976), p. 148

- ↑ Readers Digest (1976), p. 148

- ↑ Schaeffer (2001), p. 212

- ↑ Readers Digest (1976), p. 158

- ↑ How Do I Measure My Son's Inseam?: Information @JUST FOR KIX.about.com

- ↑ Maresh, Jan Saunders (2011). Sewing For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 5–43. ISBN 9781118054222.

References

- Anawalt, Patricia Rieff (2007). The Worldwide History of Dress. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51363-7.

- Dillmont, Thérèse de (1884). Encyclopedia of Needlework.

- Reader's Digest (1976). Complete Guide to Sewing. The Reader's Digest Association, Inc. ISBN 0-89577-026-1.

- Picken, Mary Brooks (1957). The Fashion Dictionary. Funk and Wagnalls.

- Schaeffer, Claire B. (2001). Couture Sewing Techniques. Taunton Press. ISBN 1-56158-497-5.