Prisoner

| Criminology and penology |

|---|

|

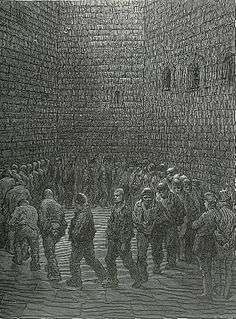

A prisoner, (also known as an inmate or detainee) is a person who is deprived of liberty against his or her will. This can be by confinement, captivity, or by forcible restraint. The term applies particularly to those on trial or serving a prison sentence in a prison.[1]

English law

"Prisoner" is a legal term for a person who is imprisoned.[2]

In section 1 of the Prison Security Act 1992, the word "prisoner" means any person for the time being in a prison as a result of any requirement imposed by a court or otherwise that he be detained in legal custody.[3]

"Prisoner" was a legal term for a person prosecuted for felony. It was not applicable to a person prosecuted for misdemeanour.[4] The abolition of the distinction between felony and misdemeanour by section 1 of the Criminal Law Act 1967 has rendered this distinction obsolete.

Glanville Williams described as "invidious" the practice of using the term "prisoner" in reference to a person who had not been convicted.[5]

History

The earliest evidence of the existence of the prisoner dates back to 8,000 BC from prehistoric graves in Lower Egypt. This evidence suggests that people from Libya enslaved a San-like tribe.[6][7]

Psychological effects

In solitary confinement

Among the most extreme adverse effects suffered by prisoners, appear to be caused by solitary confinement for long durations. When held in "Special Housing Units" (SHU), prisoners are subject to sensory deprivation and lack of social contact that can have a severe negative impact on their mental health.

Long durations may lead to depression and changes to brain physiology. In the absence of a social context that is needed to validate perceptions of their environment, prisoners become highly malleable, abnormally sensitive, and exhibit increased vulnerability to the influence of those controlling their environment. Social connection and the support provided from social interaction are prerequisite to long-term social adjustment as a prisoner.

Prisoners exhibit the paradoxical effect of social withdrawal after long periods of solitary confinement. A shift takes place from a craving for greater social contact, to a fear of it. They may grow lethargic and apathetic, and no longer be able to control their own conduct when released from solitary confinement. They can come to depend upon the prison structure to control and limit their conduct.

Long-term stays in solitary confinement can cause prisoners to develop clinical depression, and long-term impulse control disorder. Those with pre-existing mental illnesses are at a higher risk for developing psychiatric symptoms. Some common behaviours are self-mutilation, suicidal tendencies, and psychosis.

A psychopathological condition identified as "SHU syndrome" has been observed among such prisoners. Symptoms are characterized as problems with concentration and memory, distortions of perception, and hallucinations. Most convicts suffering from SHU syndrome exhibit extreme generalized anxiety and panic disorder, with some suffering amnesia.[8]

Stockholm syndrome

The psychological syndrome known as Stockholm syndrome, describes a paradoxical phenomenon where, over time, hostages develop positive feelings towards their captors.

Inmate culture

The founding of ethnographic prison sociology as a discipline, from which most of the meaningful knowledge of prison life and culture stems, is commonly credited to the publication of two key texts:[9] Donald Clemmer's The Prison Community,[10] which was first published in 1940 and republished in 1958; and Gresham Sykes classic study The Society of Captives,[11] which was also published in 1958. Clemmer's text, based on his study of 2,400 convicts over three years at the Menard Branch of the Illinois State Penitentiary where he worked as a clinical sociologist,[12] propagated the notion of the existence of a distinct inmate culture and society with values and norms antithetical to both the prison authority and the wider society.

In this world, for Clemmer, these values, formalized as the "inmate code", provided behavioural precepts that unified prisoners and fostered antagonism to prison officers and the prison institution as a whole. The process whereby inmates acquired this set of values and behavioural guidelines as they adapted to prison life he termed "prisonization", which he defined as the "taking on, in greater or lesser degree, the folkways, mores, customs and general culture of the penitentiary'.[13] However, while Clemmer argued that all prisoners experienced some degree of prisonization this was not a uniform process and factors such as the extent to which a prisoner involved himself in primary group relations in the prison and the degree to which he identified with the external society all had a considerable impact.[14]

Prisonization as the inculcation of a convict culture was defined by identification with primary groups in prison, the use of prison slang and argot,[15] the adoption of specified rituals and a hostility to prison authority in contrast to inmate solidarity and was asserted by Clemmer to create individuals who were acculturated into a criminal and deviant way of life that stymied all attempts to reform their behaviour.[16]

Opposed to these theories, several European sociologists[17] have shown that inmates were often fragmented and the links they have with society are often stronger than those forged in prison, particularly through the action of work on time perception[18]

Convict code

The convict code was theorized as a set of tacit behavioural norms which exercised a pervasive impact on the conduct of prisoners. Competency in following the routines demanded by the code partly determined the inmate’s identity as a convict.[19] As a set of values and behavioural guidelines, the convict code referred to the behaviour of inmates in antagonising staff members and to the mutual solidarity between inmates as well as the tendency to the non-disclosure to prison authorities of prisoner activities and to resistance to rehabilitation programmes.[20] Thus, it was seen as providing an expression and form of communal resistance and allowed for the psychological survival of the individual under extremely repressive and regimented systems of carceral control.[21]

Sykes outlined some of the most salient points of this code as it applied in the post-war period in the United States:

- Don't interfere with inmate interests.

- Never rat on a con.

- Don't be nosy.

- Keep off a man's back.

- Don't put a guy on the spot.

- Be loyal to your class.

- Be cool.

- Do your own time.

- Don't bring heat.

- Don't exploit inmates.

- Don't cop out.

- Be tough.

- Be wary, and try to be a man.

- Never talk to a screw.

- Have a connection.

- Be sharp.[22]

Rights

United States

Both federal and state laws govern the rights of prisoners. Prisoners in the United States do not have full rights under the Constitution, however, they are protected by Amendment VIII which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment.[23]

Growing research associates education with a number of positive outcomes for prisoners, the institution, and society. Although at the time of the ban’s enactment there was limited knowledge about the relationship between education and recidivism, there is growing merit to idea that education in prison is a preventative to re-incarceration. Several studies help illustrate the point. For example, one study in 1997 that focused on 3,200 prisoners in Maryland, Minnesota, and Ohio, showed that simply attending school behind bars reduced the likelihood of re-incarceration by 29 percent. In 2000, the Texas Department of Education conducted a longitudinal study of 883 men and women who earned college degrees while incarcerated, finding recidivism rates between 27.2 percent (completion of an AA degree) and 7.8 percent (completion of a BA degree), compared to a system-wide recidivism rate between 40 and 43 percent.10 One report, sponsored by the Correctional Education Association, focused on recidivism in three states, concluding that education prevented crime. More recently, a 2013 Department of Justice funded study from the RAND Corporation found that incarcerated individuals who participated in correctional education were 43% less likely to return to prison within 3 years than prisoners who did not participate in such programs. The research implies that education has the potential to impact recidivism rates positively by lowering them.[24]

Types

- Civilian Internees are civilians who are detained by a party to a war for security reasons. They can either be friendly, neutral, or enemy nationals.

- Convicts are prisoners that are incarcerated under the legal system. In the United States, a federal inmate is a person convicted of violating federal law, who is then incarcerated at a federal prison that exclusively houses similar criminals. The term most often applies to those convicted of a felony.

- Detainees is a frequent term used by certain governments to refer to individuals who are held in custody and are not liable to be classified and treated under the law as either prisoners of war or suspects in criminal cases. It is generally defined with the broad definition: "someone held in custody".

- Hostages are historically defined as prisoners held as security for the fulfillment of an agreement, or as a deterrent against an act of war. In modern times, it refers to someone who is seized by a criminal abductor.

- Prisoners of war, also known as a POWs, are individuals incarcerated in relation to wars. They can be either civilians affiliated with combatants, or combatants acting within the bounds of the laws and customs of war.

- Political prisoners describe those imprisoned for participation or connection to political activity. Such inmates challenge the legitimacy of the detention.

- Slaves are prisoners that are held captive for their use as labourers. Various methods have been used throughout history to deprive slaves of their liberty, including forcible restraint.

- Prisoner of conscience are anyone imprisoned because of their race, sexual orientation, religion, or political views.

Other types of prisoners can include those under police arrest, house arrest, those in insane asylums, internment camps, and peoples restricted to a specific area such as Jews in the Warsaw ghetto.

See also

- Arbitrary arrest and detention

- Civil liberties

- Detention of suspects

- History of United States Prison Systems

- Hostage

- House arrest

- Human rights

- Incarceration

- Independent custody visitor

- List of countries by incarceration rate

- Older prisoners

- Prisoner support

- Prisoner's dilemma

- Prisoners' rights

- Prison uniform

- Judicial corporal punishment

- Foot whipping

- Detention

References

- ↑ "Prisoner - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ↑ John Rastell. Termes de la Ley. 1636. Page 202. Digital copy from Google Books.

- ↑ The Prison Security Act 1992, section 1(6)

- ↑ O. Hood Phillips. A First Book of English Law. Sweet and Maxwell. Fourth Edition. 1960. Page 151.

- ↑ Glanville Williams. Learning the Law. Eleventh Edition. Stevens. 1982. Page 3, note 3.

- ↑ "Historical survey > Slave-owning societies". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh: The Slave Trade Simon and Schuster; Rockefeller Centre; New York, New York; 1997

- ↑ Bruce A. Arrigo, Jennifer Leslie Bullock (November 2007). "The Psychological Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prisoners in Supermax Units". International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 52 (6): 622. doi:10.1177/0306624X07309720.

- ↑ Simon, Jonathan (1 August 2000). "The `Society of Captives' in the Era of Hyper-Incarceration". Theoretical Criminology. 4 (3): 287. doi:10.1177/1362480600004003003. Crewe, Ben (2006). "Male prisoners’ orientations towards female officers in an English prison". Punishment & Society. 8 (4): 395–421. doi:10.1177/1462474506067565.

- ↑ Clemmer, Donald (1940). The Prison Community. New York: Holt, Rhineheart and Winston.

- ↑ Sykes, Gresham M. (1958). The Society of Captives: A Study of a Maximum Security Prison. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Clemmer, Donald (Mar–Apr 1938). "Leadership Phenomena in a Prison Community". Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 28 (6): 861 n. 1. doi:10.2307/1136755.

- ↑ DeRosia, Victoria R. (1998). Living Inside Prison Walls: Adjustment Behavior (1. publ. ed.). Westport, CT: Praeger. p. 23. ISBN 0-275-95895-7.

- ↑ Faine, John R. (Autumn 1973). "A self-consistency approach to prisonization". Sociological Quarterly. 14 (4): 576. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1973.tb01392.x.

- ↑ Pollack, Joycelyn M. (2006). Prisons: Today and Tomorrow. Ontario: Jones & Bartlett Publishers Inc. pp. 95–96. ISBN 0-7637-2904-3.

- ↑ Bright, Charles (1996). The Powers that Punish : Prison and Politics in the Era of the "Big House," 1920-2009. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-472-10732-1.

- ↑ Thomas Mathiesen, T. (1965) The Defences of the Weak: a Study of Norwegian Correctional Institution, London: Tavistock

- ↑ Guilbaud, Fabrice (2010) "Working in Prison: Time as Experienced by Inmate-Workers", 51-Annual English Selection-Supplement, p. 41-68

- ↑ Watson, Rod; Sharrock, Wes (1990). "Conversational actions and organizational actions" (PDF). 8 (2): 26.

- ↑ Brannigan, Augustine (May 1976). "Review: D. Lawrence Wieder, Language and Social Reality: The Case of Telling the Convict Code". Contemporary Sociology. 5 (3): 349. doi:10.2307/2064132.

- ↑ Colvin, Mark (February 2010). "Review: David Ward. Alcatraz: The Gangster Years". The American Historical Review. 115 (1): 247. doi:10.1086/ahr.115.1.246.

- ↑ Pollack, Joycelyn M. (2006). Prisons: Today and Tomorrow. Ontario: Jones & Bartlett Publishers Inc. p. 94. ISBN 0-7637-2904-3.

- ↑ "Prisoners' rights | LII / Legal Information Institute". Topics.law.cornell.edu. 2012-03-02. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ↑ SpearIt, Restoring Pell Grants for Prisoners- Growing Momentum for Reform http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2814358

Further reading

- Grassian, S. (1983). Psychopathological effects of solitary confinement. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140(11).

- Grassian, S., & Friedman, N. (1986). Effects of sensory deprivation in psychiatric seclusion and solitary confinement. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 8(1).

- Haney, C. (1993). "Infamous punishment": The psychological consequences of isolation. National Prison Project Journal, 8(1).

External links

| Look up prisoner, inmate, convict, or detainee in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prisoners. |

- Human Rights Watch on Detainees

- ACLU on Detainees

- Prisoner Search in U.S.A

- Victorian Prisoners' Photograph Albums from Wandsworth prison on The National Archives' website.