Inglewood Oil Field

Location of Inglewood Oil Field in southern California | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| Region | Los Angeles Basin |

| Location | Los Angeles County, California |

| Offshore/onshore | onshore |

| Operators | Freeport McMoran Oil & Gas (a division of Freeport-McMoRan) |

| Field history | |

| Discovery | 1924 |

| Start of development | 1924 |

| Start of production | 1924 |

| Peak year | 1925 |

| Production | |

| Current production of oil | 7,484 barrels per day (~3.729×105 t/a) |

| Year of current production of oil | 2013 |

| Estimated oil in place | 30.265 million barrels (~4.129×106 t) |

| Producing formations | Pico, Repetto, Topanga |

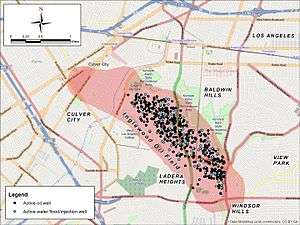

The Inglewood Oil Field in Los Angeles County, California, is the 18th-largest oil field in the state and the second-most productive in the Los Angeles Basin. Discovered in 1924 and in continuous production ever since, in 2012 it produced almost over 2.8 million barrels of oil from some five hundred wells. Since 1924 it has produced almost 400 million barrels, and the California Department of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR) has estimated that there are about 30 million barrels remaining in the field's one thousand acres, recoverable with present technology.[1]

The field is operated by Freeport McMoRan Oil & Gas, Inc, which acquired it from Plains Exploration & Production in 2013. Surrounded by Los Angeles and its suburbs, and having over one million people living within five miles of its boundary, it is the largest urban oil field in the United States.[2] Freeport has begun a vigorous program of field development through water-flooding and well stimulation to increase production, which has been slowly declining since the field's peak in 1925.

In recent years, field expansion and revitalization have been controversial with adjacent communities, which include Culver City, Baldwin Hills, and Ladera Heights. Several organizations have formed to oppose field development, in particular the proposed use of hydraulic fracturing as a well stimulation technique. In response, to assuage the fears of the surrounding community, Freeport McMoran's consultants have published reports attempting to show that such practices are safe. Additionally, in 2008 the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors adopted a Community Standards District (CSD) for Baldwin Hills, specifically to regulate development and operations in the oil field to make it compliant with community environmental standards.

Geographic setting

The Inglewood Oil Field underlies the Baldwin Hills, a range of low hills near the northern end of the Newport–Inglewood Fault Zone. The hills are cut by numerous canyons, and include a central depression along the east side of which is a scarp representing the surface trace of the Newport–Inglewood Fault. The hills terminate abruptly on the north, east, and west, and slope gradually down to the south. Surface drainage from the hills is generally south and west, with runoff from the oil field going into six retention basins which drain into the Los Angeles County storm drainage network, and then into either Centinela Creek or Ballona Creek.[3]

Climate in the area is Mediterranean, with cool rainy winters and mild summers, with the heat moderated by morning fog and low clouds. The field contains both native and non-native vegetation, primarily on hillsides and in the narrow areas between drilling pads, tank farms, and work areas, as the field is densely developed. Surrounding land use is residential, recreational, commercial, and industrial, including high-density housing. Racial makeup of the population living within one mile of the field boundary in 2006 was approximately 50% African-American and 15% Hispanic.[4] The 338-acre Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area is adjacent to the oilfield on the northeast.[5]

The oilfield is unusual in urban Los Angeles in being entirely open to view, developed in the traditional manner of individual pumpjacks on drilling pads. Most other oil fields in the entirely urbanized parts of Los Angeles, such as the Beverly Hills and Salt Lake fields, hide their pumping and drilling equipment, storage tanks, and other operations in large windowless buildings disguised to blend in with the urban landscape.

Geology

The Inglewood Oil Field is along the Newport–Inglewood Fault, which is one of several major faults running through the Los Angeles Basin. Several large oil and gas fields have accumulated along the fault zone where motion along the fault has positioned impermeable rock units in the path of hydrocarbon migration, forming structural traps. Other fields along the same fault zone include the Beverly Hills Oil Field to the north, and the Long Beach Oil Field to the south.[6] The Baldwin Hills region is complexly faulted, with the primary Newport–Inglewood Fault on the northeast, another parallel fault to the southwest, a structural block between them offset downwards vertically (a graben), and the entire region criss-crossed by even smaller faults perpendicular to the main Newport–Inglewood zone.

The field is within a layer-cake of Pliocene- and Miocene-age sediments, with multiple producing zones stacked vertically, each zone within a permeable rock layer separated from the others by impermeable layers. Above the oil field's producing zones is a layer of alluvium of Holocene and Pleistocene age.[7] Nine pools have been identified within the oil field, given in order from top to bottom, with geologic formation, average depth below ground surface, and date of discovery:[8]

- Upper Investment (Pico Formation, 950 feet, 1948)

- Investment (Pico/Repetto Formation, 1,050 feet, 1924)

- Vickers (Repetto Formation, 1,500 feet, 1924)

- Rindge (Repetto Formation, 2,400 feet, 1925)

- Rubel (Repetto Formation, 3,400 feet, 1934)

- Moynier (Repetto Formation, 4,200 feet, 1932)

- Bradna (Puente Formation, 8,000 feet, 1957)

- Sentous (Topanga Formation, 8,200 feet, 1940)

- City of Inglewood (Puente Formation, 9,000 feet, 1960)

Groundwater in the vicinity of the oil field was formerly thought to exist only in perched zones not connected to the major aquifers of the Los Angeles Basin, and found mainly in canyon sediments and weathered bedrock.[9] However, more recent modeling of regional groundwater occurrence and dynamics suggests that the Newport–Inglewood Fault is only a partial barrier to groundwater, and some hydraulic communication between the groundwater in the Baldwin Hills and the surrounding aquifers exists. Since the hills are higher than the adjoining plains, groundwater would necessarily move outward from the hills and the oilfield area.[10] The base of fresh water in the oilfield area varies from about 200 to 350 feet below ground surface.[11]

History

Oil has been known in the Los Angeles basin since prehistoric times. Not far from the Inglewood field, the La Brea Tar Pits are a surface expression of the Salt Lake Oil Field; crude oil seeps to the surface along a fault, biodegrading to asphalt. The native inhabitants of the region used the tar for many purposes, including as a sealant, and the first European settlers found similar uses. In the mid-19th century, oil had become a valuable commodity as an energy source, commencing a period of exploration and discovery for its sources. By the 1890s, prospectors were drilling for oil in the basin, and in 1893 the first large field – the Los Angeles City Oil Field, adjacent and underneath the then-small city of Los Angeles – became the largest oil producer in the state. Oil companies began finding other rich fields not far away, such as the Beverly Hills and Salt Lake fields. In the 1920s drillers began exploring the long band of hills along the Newport–Inglewood Fault zone, suspecting it was an anticlinal structure capable of holding oil, and they were not disappointed, as the huge fields along the zone were discovered one after another: the Huntington Beach Oil Field in 1920, the Long Beach Oil Field in 1921, the Dominguez Oil Field in 1923, and both the Inglewood Oil Field and Rosecrans fields in 1924.[12][13]

The Baldwin Hills area had tempted drillers for years, but all early attempts to find oil were unsuccessful, probably because erosion and faulting made the anticlinal structure appear farther east than it really was.[14] The first well to find oil was completed September 28, 1924 by Standard Oil Company, one of the predecessors of Chevron Corporation. Development of the field commenced rapidly but in a more orderly way than was usual for a Los Angeles Basin oil field.[15] Peak production occurred less than a year after the first well was installed. The first companies to work the field were Associated Oil Company, California Petroleum Corporation, O.R. Howard & Company, Mohawk Oil and Gas Syndicate, Petroleum Securities Company, Shell Company of California, and Standard Oil Company of California.[16]

Production declined through the late 1920s and 1930s, as other fields came online and the Great Depression reduced demand. Production increased briefly in the war years of the 1940s before declining again.[17] In 1953, the field operators began using waterflooding, the earliest enhanced oil recovery technique, to increase reservoir pressure and make oil extraction easier. In 1964 cyclic steaming, another enhanced recovery technique, began, resulting in a bulge in production through the 1960s before entering a period of steady decline that persisted until after 2000.[11][17]

Baldwin Hills Dam disaster

North of the oil field, the Baldwin Hills once contained a reservoir behind a dam built between 1947 and 1951. On the afternoon of December 14, 1963, the dam collapsed, sending a wall of water north through the neighborhoods, roughly along Cloverdale Avenue, killing 5 people, destroying 65 houses and damaging hundreds more.[18] The cause of the collapse was not immediately known, but investigations over the following decades implicated oilfield operations – specifically subsidence due to extraction of hundreds of millions of barrels of oil and water over the preceding decades.[19] The site of the reservoir is now part of the Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area.

Redevelopment

In 1977, Standard Oil became part of Chevron Corporation. Chevron, the sole operator remaining on the field, having absorbed or bought out all the smaller operators over the years, sold it to Stocker Resources in 1990 at a time when many of the major oil companies were divesting their onshore assets in California. Stocker was acquired by Plains Resources, Inc., the predecessor to Plains Exploration & Production (PXP) in 1992. In 2002 PXP was incorporated, including Plains Resources, and PXP operated the field until Freeport McMoran acquired them in 2013.[20]

The field had long been in decline, and neighborhood residents had long understood, without having an agreement in writing, that the field operators would eventually abandon and remediate the field. This would allow Baldwin Hills and the other nearby communities to create a 2000-acre urban park, the largest urban park in the United States to be created in over 100 years, a greenspace in an area otherwise almost devoid of parks.[21] Unfortunately for those plans, PXP begin a vigorous program of field redevelopment in the early 2000s after seismic testing and modeling showed more unrecovered oil than previously believed.[2]

In January 2006, drillers encountered a pocket of methane gas while pushing through a shale unit. The resulting gas cloud, released from the top of the drilling rig and enhanced with fragrance from contaminated drilling mud, drifted over the houses to the south, resulting in the midnight evacuation of the Culver Crest neighborhood, residents having been alarmed by the foul smell. For this incident PXP received a Notice of Violation from the South Coast Air Quality Management District, who had received about 60 separate citizen complaints that night. A month later another noxious gas release from the field further outraged area residents.[2][22]

To assuage community concerns, Los Angeles County imposed a drilling moratorium on PXP while they worked together with the oil company to develop a Community Standards District (CSD) for Baldwin Hills.[2] A CSD is a Los Angeles planning document – essentially a series of supplmental, enforceable regulations – that address concerns specific to a geographic area. In the case of Baldwin Hills, that meant curtailing or mitigating noxious impacts from the oilfield operations.[23]

Hydraulic fracturing controversy

One of the causes of controversy, and a major fear of area residents, is the potential earthquake risk from using hydraulic fracturing ("fracking") on the field. PXP, and later Freeport McMoRan, have been open with their plans to use the technique on several new wells. The field straddles the Newport–Inglewood Fault, a seismic hazard the United States Geological Survey (USGS) has judged capable of a 7.4 MW magnitude earthquake.[24] Additionally, residents fear that hydraulic fracturing may result in groundwater contamination and other environmental and health problems.[25]

In 2008, community groups filed suit against Los Angeles County and PXP, questioning the effectiveness of the Community Standards District. The various parties settled the suit in 2011, agreeing on scaled-back field development, greater noise and air pollution protection, and in addition, PXP was required to commission an outside consultant to do a thorough study of the potential effects of hydraulic fracturing on the oilfield and surrounding communities. The hydraulic fracturing report was published October 2012. Its findings were principally in line with what PXP had originally said, that hydraulic fracturing would have no adverse impact on the communities; however this was criticized vigorously by community organizations, who alleged, among other things, that some of the consultants were not sufficiently independent of the oil company.[25][26][27]

Activity and controversy on the Inglewood field takes place in an environment of increasing public and regulatory scrutiny of the practice of hydraulic fracturing. In 2013, California Senate Bill 4 required the California Department of Conservation to produce a draft and final Environmental Impact Report on the statewide use of the technique. The final EIR was certified July 1, 2015.[28]

In October 2015, Culver City proposed its own rules for the portion of the field within its limits, including new buffers between drilling sites and homes, and whether or not to allow hydraulic fracturing.[29]

Operations

Oil recovered from the Inglewood field is processed onsite to remove water and gas. Produced water – water pumped up from the formation along with the oil – is reinjected into the formation by means of a series of water injection wells scattered throughout the oilfield. Gas is processed onsite to remove hydrogen sulfide and other contaminants, and once it is of marketable quality is sold to the Southern California Gas Company. Oil after processing is temporarily stored in tank farms onsite and moved by pipeline to the sales facility in the northeastern part of the oil field, immediately south of the Community Center at Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area.[30] Oil is sold and transported away from the field in a pipeline owned by Chevron to area refineries where it is mostly made into gasoline for sale in the Southern California market.[31]

The sales terminal at the northeastern part of the oilfield also receives crude oil, gas, and produced water by pipeline from Freeport McMoRan's drilling island at the Beverly Hills Oil Field on Pico Boulevard.[32]

References

- California Oil and Gas Fields, Volumes I, II and III. Vol. I (1998), Vol. II (1992), Vol. III (1982). California Department of Conservation, Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources ("DOGGR"). 1,472 pp. Inglewood Oil Field information pp. 192–194. PDF file available on CD from www.consrv.ca.gov.

- "2009 Report of the state oil & gas supervisor" (PDF). Department of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources. California Department of Conservation. 2010. Retrieved January 1, 2015. ("DOGGR 2010")

- "SB4 Final Environmental Impact Report". California Department of Conservation. July 1, 2015. Retrieved January 3, 2016. ("SB4 EIR")

- García, Robert; Meerkatz, Elise; Strongin, Seth (May 2010). "Keeping the Baldwin Hills Clean and Green for Generations to Come" (PDF). Concerned Citizens of South Central Los Angeles, The City Project. Retrieved January 4, 2016. ("García, Meerkatz, Strongin")

- "Hydraulic Fracturing Study: PXP Inglewood Oil Field" (PDF). Cardno Entrix. October 10, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2015. ("Entrix")

- Vives, Ruben (June 23, 2012). "Inglewood Oil Field's neighbors want answers about land shift". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- Rodriguez, Ashlie (July 7, 2011). "Culver City groups settle suit with oil company, L.A. County". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

Notes

- ↑ DOGGR 2010, p. 65

- 1 2 3 4 Vives, Ruben (June 23, 2012). "Inglewood Oil Field's neighbors want answers about land shift". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- ↑ Baldwin Hills EIR, p. 4.6-1

- ↑ Baldwin Hills EIR, ES-5

- ↑ "Kenneth Hahn State Recreation area". Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ↑ Huguenin, E. Inglewood Oil Field: Summary of Operations, California Oil Fields. California State Mining Bureau, State Oil and Gas Supervisor. 1926. Vol. 11 No 12, p. 5

- ↑ DOGGR, p. 192

- ↑ DOGGR, p. 193-4

- ↑ Ramboll, p. 3

- ↑ SB4 EIR, p. C.7-46

- 1 2 DOGGR, p. 193

- ↑ "Oil and Gas Production: History in California" (PDF). California Department of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR). California Department of Conservation. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ↑ DOGGR, p. 429, etc.

- ↑ Huguenin, p. 9

- ↑ Huguenin, p. 5, 15

- ↑ Huguenin, p. 5

- 1 2 CSD EIR, p. 2-12

- ↑ http://framework.latimes.com/2013/12/13/the-1963-baldwin-hills-dam-collapse/#/0 Baldwin Hills dam collapse

- ↑ Jansen, R.B. (2012). Advanced Dam Engineering for Design, Construction, and Rehabilitation. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 125. ISBN 1461308577.

- ↑ "Hydraulic Fracturing Study: PXP Inglewood Oil Field" (PDF). Cardno Entrix. October 10, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ↑ García, Meerkatz, Strongin, p. 19-22

- ↑ García, Meerkatz, Strongin, p. 28

- ↑ "Community Standards Districts". Los Angeles County Department of Regional Planning. June 29, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ↑ Tessa Stuart (May 17, 2012). "Could fracking in Los Angeles cause an earthquake?". LA Weekly. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- 1 2 Ruben Vives (October 15, 2012). "Baldwin Hills fracking study is questioned". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ↑ Entrix, p. ES 1-4

- ↑ Vives, Ruben (October 10, 2012). "Inglewood Oil Field fracking study finds no harm from the method". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ↑ "SB4 Final Environmental Impact Report". California Department of Conservation. July 1, 2015. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ↑ "New rules for Inglewood Oil Field to be proposed by Culver City". Southern California Public Radio. October 22, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ↑ Baldwin Hills EIR, p. 2-15

- ↑ Baldwin Hills EIR, p. 2-14

- ↑ Baldwin Hills EIR, p. 2-11

Coordinates: 34°00′17″N 118°22′08″W / 34.0047°N 118.3690°W