Inductive effect

In chemistry and physics, the inductive effect is an experimentally observable effect of the transmission of charge through a chain of atoms in a molecule, resulting in a permanent dipole in a bond.[1] It is present in a σ bond as opposed to the electromeric effect which is present on a π bond. All halides are withdrawing groups

Bond polarization

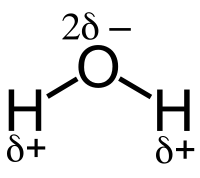

Covalent bonds can be polarized depending on the relative electronegativity of the atoms forming the bond. The electron cloud in a σ-bond between two unlike atoms is not uniform and is slightly displaced towards the more electronegative of the two atoms. This causes a permanent state of bond polarization, where the more electronegative atom has a fractional negative charge (δ–) and the less electronegative atom has a fractional positive charge (δ+).

For example, the water molecule H2O has an electronegative oxygen atom that attracts a negative charge. This is indicated by δ- in the water molecule in the vicinity of the O atom, as well as by a δ+ next to each of the two H atoms. The vector addition of the individual bond dipole moments results in a net dipole moment for the molecule.

Inductive effect

If the electronegative atom is then joined to a chain of atoms, usually carbon, the positive charge is relayed to the other atoms in the chain. This is the electron-withdrawing inductive effect, also known as the effect.

However, some groups, such as the alkyl group, are less electron-withdrawing than hydrogen and are therefore considered as electron-releasing. This is electron-releasing character and is indicated by the effect. In short, alkyl groups tend to give electrons, leading to induction effect.

As the induced change in polarity is less than the original polarity, the inductive effect rapidly dies out and is significant only over a short distance. Moreover, the inductive effect is permanent but feeble since it involves the shift of strongly held σ-bond electrons and other stronger factors may overshadow this effect.

Relative inductive effects

Relative inductive effects have been experimentally measured with reference to hydrogen, in decreasing order of -I effect or increasing order of +I effect, as follows:

- –NH3+ > –NO2 > –SO2R > –CN > –SO3H > –CHO > –CO > –COOH > –COCl> –CONH2 >

–F > –Cl > –Br > –I > –OR > -OH > –NH2 > –C6H5 > –CH=CH2 > –H

The strength of inductive effect is also dependent on the distance between the substituent group and the main group that react; the greater the distance, the weaker the effect.

Inductive effects can be measured through the Hammett equation, which describes the relationship between reaction rates and equilibrium constants with respect to substituents.

Fragmentation

The inductive effect can be used to determine the stability of a molecule depending on the charge present on the atom and the groups bonded to the atom. For example, if an atom has a positive charge and is attached to a −I group its charge becomes 'amplified' and the molecule becomes more unstable. Similarly, if an atom has a negative charge and is attached to a +I group its charge becomes 'amplified' and the molecule becomes more unstable. In contrast, if an atom has a negative charge and is attached to a −I group its charge becomes 'de-amplified' and the molecule becomes more stable than if I-effect was not taken into consideration. Similarly, if an atom has a positive charge and is attached to a +I group its charge becomes 'de-amplified' and the molecule becomes more stable than if I-effect was not taken into consideration. The explanation for the above is given by the fact that more charge on an atom decreases stability and less charge on an atom increases stability

Acidity and basicity

The inductive effect also plays a vital role in deciding the acidity and basicity of a molecule. Groups having +I effect attached to a molecule increases the overall electron density on the molecule and the molecule is able to donate electrons, making it basic. Similarly, groups having -I effect attached to a molecule decreases the overall electron density on the molecule making it electron deficient which results in its acidity. As the number of -I groups attached to a molecule increases, its acidity increases; as the number of +I groups on a molecule increases, its basicity increases.

Applications

Carboxylic acids

The strength of a carboxylic acid depends on the extent of its [ionization]: the more ionized it is, the stronger it is. As an acid becomes stronger, the numerical value of its pKa drops.

In acids, the electron-releasing inductive effect of the alkyl group increases the electron density on oxygen and thus hinders the breaking of the O-H bond, which consequently reduces the ionization. Greater ionization in formic acid when compared it to acetic acid makes formic acid (pKa=3.74) stronger than acetic acid (pKa=4.76). Monochloroacetic acid (pKa=2.82), though, is stronger than formic acid, since the electron-withdrawing effect of chlorine promotes ionization.

In benzoic acid, the carbon atoms which are present in the ring are sp2 hybridised. As a result, benzoic acid (pKa=4.20) is a stronger acid than cyclohexanecarboxylic acid (pKa=4.87). Also, in aromatic carboxylic acids, electron-withdrawing groups substituted at the ortho and para positions can enhance the acid strength.

Since the carboxyl group is itself an electron-withdrawing group, dicarboxylic acids are, in general, stronger than their monocarboxyl analogues. The Inductive effect will also help in polarization of a bond making certain carbon atom or other atom positions.

Comparision between Inductive effect and Electromeric effect

| Inductive Effect | Electromeric Effect |

|---|---|

| The polarization of single σ covalent bond due to the electronegativity difference between the bonding atoms is called inductive effect | The complete shift of the π bond electron pair of a double bond or triple bond to one of the atoms joined by it in the presence of a suitable electrophilic reagent is called electromeric effect |

| It is a permanent effect | It is a temporary effect |

| It doesn't need the presence of a reagent | It needs the presence of an electrophilic reagent |

See also

- Pi backbonding

- Baker–Nathan effect: the observed order in electron-releasing basic substituents is apparently reversed.

References

- ↑ Richard Daley. Organic Chemistry, Part 1 of 3. Lulu.com. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-1-304-67486-9.

- Stock, Leon M. (1972). "The origin of the inductive effect". Journal of Chemical Education. 49 (6): 400. ISSN 0021-9584. doi:10.1021/ed049p400.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Inductive effect |