Indre Wijdefjorden National Park

| Indre Wijdefjorden National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

| |

| |

| Location | Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway |

| Nearest city | Longyearbyen |

| Coordinates | 79°N 16°E / 79°N 16°ECoordinates: 79°N 16°E / 79°N 16°E |

| Area |

1,127 km2 (435 sq mi), of which 745 km2 (288 sq mi) is land 382 km2 (147 sq mi) is water |

| Established | 9 September 2005 |

| Governing body | Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management |

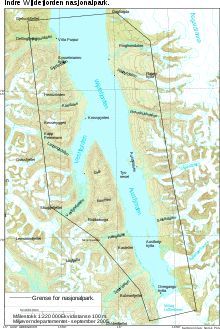

Indre Wijdefjorden National Park (Norwegian: Indre Wijdefjorden nasjonalpark) is located in a steep fjord landscape in northern Spitsbergen in Svalbard, Norway. It covers the inner part of Wijdefjorden—the longest fjord on Svalbard. The national park was established on 9 September 2005 and covers 1,127 km2 (435 sq mi), of which 745 km2 (288 sq mi) is on land and 382 km2 (147 sq mi) is sea. The marine environment changes vastly from the mouth of the fjord, through a still, cold, water basin, becoming deeper before reaching the glacier Mittag-Lefflerbreen at the inner-most sections of the fjord.

On both sides of Wijdefjorden there is High Arctic steppe vegetation, dominated by grasses and extremely dry, basic earth. There are some areas dominated by exposure of mineral earth. The area around the fjord has a vegetation which is unique and not preserved in other areas of Svalbard. Along with vegetation found on nesting cliffs, it is the most exclusive flora in Svalbard. There are several exclusive species in the national park, including Stepperøykvein, Puccinellia svalbardensis, Gentianella tenella and Kobresia simpliciuscula. Of the larger fjords on Svalbard, Wijdefjorden is the least affected by humans, although a trapping station has been built at Austfjordnes.

Geography

Indre Wijdefjorden National Park covers 1,127 km2 (435 sq mi), of which 745 km2 (288 sq mi) is on land and 382 km2 (147 sq mi) is sea, making it the smallest national park in Svalbard. It is located in the steep fjord landscape on both sides of the inner ("Indre") parts of Wijdefjorden ("The Wide Fjord") on Spitsbergen.[1] At 108 kilometres (67 mi) length, Wijdefjorden is the longest fjord on Svalbard. It is located on the northern coast of Spitsbergen, between Andrée Land to the west, Dickson Land to the south and Ny-Friesland to the east.[2] The inner parts of Wijdefjorden split into two, with the eastern, 32-kilometre (20 mi) long part known as Austfjorden ("The East Fjord"),[3] and the shorter as Vestfjorden ("The West Fjord").[4] At the end of Austfjorden is the glacier Mittag-Lefflerbreen.[5]

The inner parts of the fjord receive some of the lowest precipitation of the archipelago. Combined with the exposed basic earth, this results in Europe's only High Arctic steppe. The only other area with this landscape is the north of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The rock bed on each side of the fjord is different. On the west side there are Devonian deposits, while there is bedrock on the east side, resulting in different vegetation on each side.[6] The fjord has a unique shape; it has a wide mouth (thus the name), but at Elvetangen there is a shallow section which is 50 metres (160 ft) deep. This reduces the circulation in the inner parts of the fjord, which have a cold-water basin 250 metres (820 ft) deep.[7]

Average July temperatures range from 4 to 6 °C (39 to 43 °F), and in January temperatures are normally between −12 and −16 °C (10 and 3 °F).[8] The Arctic climate results in permafrost, which can be up to 100 metres (330 ft) deep.[9] The North Atlantic Current moderates Svalbard's temperatures, particularly during winter, giving it up to 20 °C (36 °F) higher winter temperature than similar latitudes in continental Russia and Canada, keeping the surrounding waters open and navigable most of the year. The shelter of the mountains gives the inland fjord areas less temperature difference than the coast.[10]

History

The area around Wijdefjorden was first used by Russian, and later Norwegian, trappers. The cabin at Krosspynten was erected in 1910, and two years later the cabin at Purpurdalen was built. Trappers considered the area to have few polar bears but much fox; they could also supplement the catch with common eider. In 1928, a season of trapping gave about 50 Arctic foxes.[7] In 1932, the area's special vegetation was protected, which was assimilated into the national park when it was created.[6] Since the 1980s, trapping has again been taken up, and the Governor of Svalbard has one cabin at Austfjordnes that can be rented for a season of trapping.[7] Of the larger fjords on Svalbard, Wijdefjorden is the least affected by humans.[11]

During the considerations prior to the establishment of the national park, there was a conflict with the mining industry. Svalbard Minerals had found baryte within the national park borders, and Arktikugol holds two mining claim areas just south of the national park.[12] The national park was established on 9 September 2005. It completed a several-year-long plan to increase the amount of protected areas of Svalbard from 55% to 65%, which had two years earlier resulted in Nordenskiöld Land National Park, Sassen – Bünsow Land National Park and Nordre Isfjorden National Park.[13]

Management

The establishment of the national park and the protection is based on the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act, which takes its mandate from the requirements in the Svalbard Treaty to protect the environment of the archipelago.[14] The overall responsibility for protection lies with the Norwegian Ministry of the Environment, which has delegated management to the Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management and the Governor of Svalbard. The latter performs all day-to-day practical management, including registration and inspection. In aspects related to cultural heritage, the Governor reports to the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage, and in issues relating to pollution, to the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority. While it has no authority, the Norwegian Polar Institute performs monitoring, mapping and research.[15]

Traditionally, the mining industry in Svalbard has had more rights to operations within protected areas than in mainland Norway, where all such activities would be completely banned. Indre Wijdefjorden has the most strict regulations, with a total ban on construction of buildings and facilities, laying of cables and roads, earthwork, drainage, drilling, blasting, and excavation of petroleum, gas and minerals.[16] It is the authorities' goal that Svalbard is to be one of the best-managed wilderness areas in the world.[17] Svalbard, and thus the national park, is on Norway's tentative list for nomination as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[18]

Nature

The vegetation on both sides of the fjord is High Arctic steppe, which is characterized by grasses. It is caused by extremely low precipitation, basic earth with salt deposits in the surface, and large areas of exposed mineral earth.[19] The area around the fjord has a unique vegetation, which has not preserved in other areas of Svalbard. Along with vegetation found on nesting cliffs, it is the most exclusive flora in Svalbard. There are several unique species in the national park, including Stepperøykvein, which is featured in the national park's logo and for which Svalbard is the only known location in Europe, Puccinellia svalbardensis, Gentianella tenella and Kobresia simpliciuscula.[20] There is breeding ground for pink-footed goose within the park,[7] although Svalbard ptarmigan can also be found.[21] Animals that can be found in the park include polar bear, Svalbard reindeer and Arctic fox.[22]

Both fauna and flora are affected by the cold temperatures and the extreme light conditions. Activity is at a stand-still during the polar night, which lasts for many months. During the summer, months of midnight sun help accelerate the natural processes.[22] The nature in the area is especially susceptible to global warming. Models show that the winter temperatures will increase more than the summer temperatures, resulting in more precipitation. Because the vegetation requires little rain and much wind, this may result in major changes.[6]

Recreation

Entrance to national park is available by boat in Wijdefjorden from the north, or over land from Billefjorden and Dicksonfjorden from the south. During winter, the area is accessible from Longyearbyen, either by snowmobile or by ski. There are several older trapper cabins in the park, and some of these are lent to residents of Longyearbyen.[23] Except for Einsteinvatnet, a lake with Arctic char, there are few destinations within the park, although the park can be used as a basis for other destinations. This includes trips to Perriertoppen, Svalbard's second-highest peak, and the glacier Åsgårdsfonna. Because of the shape of the park, there is little good hiking within the park, except for walking along the beaches on either side of the fjord. It is possible to see the entire national park from Mittag-Lefflerbreen, which can be hiked to from Pyramiden.[24]

The freedom to roam is strong in Norwegian culture and law, and also applies to Svalbard. However, there more restrictions on the archipelago.[25] The freedom includes the right to tent, but this must be done at least 100 metres (330 ft) from any cultural monuments. As far as possible, tenting must occur on vegetation-free land. Tenting for more than one week at a site requires a permit from the Governor. Beaches have large amounts of driftwood from Siberia, which can be used for campfires with the same location restrictions as tenting.[26]

As in all Norwegian national parks, motorized land transport is banned. However, on Svalbard this does not include snowmobiles. On the other hand, cycling is banned.[27] The Governor can, however, enforce temporary bans on snowmobiles or even all travel within the national park.[14] Use of helicopters and aircraft for sight-seeing are also prohibited.[28] Polar bears are protected, but anyone outside of settlements is required to carry a rifle to kill polar bears in self-defense, as a last resort, should they attack.[29] Most flora and fauna are protected; the right to gather established with the freedom to roam does not apply in national parks, although there are some exceptions. Hunting is permitted after explicit permit from the Governor, and locals have more access to hunting rights than tourists.[30] Fishing is not permitted, although dispensations can be given.[31]

All tourists traveling to Svalbard must pay a tourist tax of 150 Norwegian krone, which is entirely used for conservation. The tax is included in all ship and air tickets to the archipelago, which residents can get refunded.[32] Everyone roaming outside of the settlements must report to the Governor.[33] This includes the requirement to sign a special insurance policy to cover any search and rescue costs the Governor would incur, should it be necessary.[34]

References

- ↑ "Særpreget planteliv rundt Svalbards lengste fjord" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ "Wijdefjorden". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ "Austfjorden". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ "Vestfjorden". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ "Mittag-Lefflerbreen". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 Aasheim (2008): 129

- 1 2 3 4 Aasheim (2008): 130

- ↑ "Temperaturnormaler for Spitsbergen i perioden 1961 – 1990" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Meteorological Institute. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 19

- ↑ Torkilsen (1984): 98–99

- ↑ "Menneskelig aktivitet" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ Rapp, Ole Magnus (23 May 2005). "Stepper blir nasjonalpark". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ Hareide, Knut Arild (9 September 2005). "Fullfører nå vern av villmarksnaturen på Svalbard" (in Norwegian). Government.no. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- 1 2 Aasheim (2008): 47

- ↑ "Protected Areas in Svalbard" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. p. 34. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 53

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 57

- ↑ "Svalbard". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ "Høyarktiske steppeområder" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ "Unik vegetasjon og sjelden flora" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate for Nature Management. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 40

- 1 2 Aasheim (2008): 27

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 131

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 132

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 75

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 81

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 82

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 83

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 77

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 83

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 84

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 56

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 80

- ↑ Aasheim (2008): 81

Bibliography

- Aasheim, Stein P. (2008). Norges nasjonalparker: Svalbard (in Norwegian). Oslo: Gyldendal. ISBN 978-82-05-37128-6.

- Torkildsen, Torbjørn; et al. (1984). Svalbard: vårt nordligste Norge (in Norwegian). Oslo: Forlaget Det Beste. ISBN 82-7010-167-2.