Wayfinding

Wayfinding encompasses all of the ways in which people (and animals) orient themselves in physical space and navigate from place to place.

Basic process

The basic process of wayfinding involves four stages:

- Orientation is the attempt to determine one's location, in relation to objects that may be nearby and the desired destination.

- Route decision is the selection of a course of direction to the destination.

- Route monitoring is checking to make sure that the selected route is heading towards the destination.

- Destination recognition is when the destination is recognized.[1]

Historical

Historically, wayfinding refers to the techniques used by travelers over land and sea to find relatively unmarked and often mislabeled routes. These include but are not limited to dead reckoning, map and compass, astronomical positioning and, more recently, global positioning.

Wayfinding can also refer to the traditional navigation method used by indigenous peoples of Polynesia.[2] The ancient Polynesians and Pacific Islanders mastered the way of wayfinding to explore and settle on the islands of the Pacific, many using devices such as the Marshall Islands stick chart. With these skills, some of them were even able to navigate the ocean as well as they could navigate their own land. Despite the dangers of being out at sea for a long time, wayfinding was a way of life.[3] Today, The Polynesian Voyaging Society tries-out the traditional Polynesian ways of navigation. In October 2014, the crew of the Hokuleʻa arrived on another island in Tonga. [7]

Modern usage of the term

Recently, wayfinding has been used in the context of architecture to refer to the user experience of orientation and choosing a path within the built environment. Kevin A. Lynch used the term for his 1960 book The Image of the City, where he defined wayfinding as "a consistent use and organization of definite sensory cues from the external environment."

In 1984 environmental psychologist Romedi Passini published the full-length "Wayfinding in Architecture" and expanded the concept to include the use of signage and other graphic communication, visual clues in the built environment, audible communication, tactile elements, including provisions for special-needs users.

The wayfinding concept was further expanded in a further book by renowned Canadian graphic designer Paul Arthur, and Romedi Passini, published in 1992, "Wayfinding: People, Signs and Architecture." The book serves as a veritable wayfinding bible of descriptions, illustrations, and lists, all set into a practical context of how people use both signs and other wayfinding cues to find their way in complex environments. There is an extensive bibliography, including information on exiting information and how effective it has been during emergencies such as fires in public places.[4]

Wayfinding also refers to the set of architectural or design elements that aid orientation. Today, the term wayshowing, coined by Per Mollerup,[5] is used to cover the act of assisting way finding.[6] describes the difference between wayshowing and way finding, and codifies the nine wayfinding strategies we all use when navigating in unknown territories. However, there is some debate over the importance of using the term wayshowing, some argue that it merely adds confusion to a discipline that is already highly misunderstood.

In 2010 AHA Press Published "WAYFINDING FOR HEALTHCARE Best Practices for Today's Facilities", written by Randy R. Cooper. The book takes a comprehensive view of Wayfinding specifically for those in search of medical care.[7]

Whilst wayfinding applies to cross disciplinary practices including architecture, art and design, signage design, psychology, environmental studies, one of the most recent definitions by Paul Symonds [8] defines wayfinding as "The cognitive, social and corporeal process and experience of locating, following or discovering a route through and to a given space". Wayfinding is an embodied and sociocultural activity in addition to being a cognitive process in that wayfinding takes places almost exclusively in social environments with, around and past other peoples and influenced by stakeholders who manage and control the routes through which we try to find our way. The route is often one we might take for pleasure, such as to see a scenic highway, or one we take as a physical challenge such as trying to find the way through a set of underground caves. Wayfinding is a complex practice that very often involves techniques such as people-asking (asking people for directions) and crowd following and is thus a practice that combines psychological and sociocultural processes.

Wayfinding in architecture, signage and urban planning

Modern wayfinding has begun to incorporate research on why people get lost, how they react to signage and how these systems can be improved.

Urban planning

An example of an urban wayfinding scheme is the Legible London Wayfinding system.

Nashville, Tennessee has introduced a live music wayfinding plan. Posted outside each live music venue is a guitar pick reading Live Music Venue.[9]

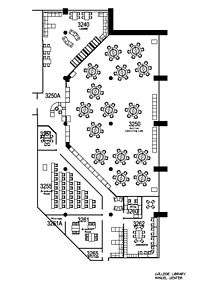

Indoor wayfinding

Indoor wayfinding in public buildings such as hospitals is commonly aided by kiosks,[10] indoor maps, and building directories. Such spaces that involve areas outside the normal vocabulary of visitors show the need for a common set of language-independent symbols. Offering indoor maps for handheld mobile devices is becoming common, as are digital information kiosk systems. Other frequent wayfinding aids are the use of color coding[11] and signage clustering.[12]

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) represented a milestone in helping to make spaces universally accessible and improving wayfinding for users.

See also

- Desire path

- Environmental psychology

- Location-based service

- Orienteering

- Space syntax

- Trail blazing (Waymarking)

- Urban planning

- Wayfinding software

Further reading

- Chris Calori (2007), Signage and Wayfinding Design: A Complete Guide to Creating Environmental Graphic Design Systems, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-465-06710-7

- Environmental Graphics: Projects and Process from Hunt Design.

Paul Arthur and Romedi Passini "Wayfinding: People, Signs and Architecture", (originally published 1992, McGraw Hill, reissued in a limited commemorative edition in 2002 by SEGD). ISBN 978-0075510161, ISBN 0075510162

References

- ↑ Lidwell, William, Kritina Holden and Jill Butler. Universal Principles of Design. (Rockport Publishers, Beverly, MA, 2010) p. 260. Link at Google Books.

- ↑ Polynesian Voyaging Society (2009)

- ↑ Daniel Lin, "Hokuleʻa: The Art of Wayfinding (Interview with a Master Navigator)," National Geographic website, 3 March 2014, retrieved on 29 October 2014.

- ↑ Originally published 1992, McGraw Hill, reissued in a limited commemorative edition in 2002 by SEGD. ISBN 978-0075510161

- ↑ Per Mollerup, Wayshowing, A Guide to Environmental Signage (Lars Muller Publisher)

- ↑ Per Mollerup, Wayshowing>Wayfinding: Basic & Interactive (BIS Publishers)

- ↑ AHA Press, Health Forum Inc., An American Hospital Association Company - Chicago

- ↑ Paul Symonds, " Wayfinding as an Embodied Sociocultural Experience" “Sociological Research Online website, 28 February 2017, retrieved on 17 April 2017.

- ↑

- ↑ Raven, A., Laberge, J., Ganton, J. & Johnson, M., Wayfinding in a Hospital: Electronic Kiosks Point the Way, UX Magazine 14.3, September 2014.

- ↑

- ↑