Indo-Roman trade relations

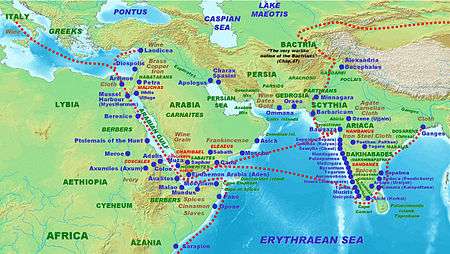

Indo-Roman trade relations (see also the spice trade and incense road) was trade between the Indian subcontinent and the Roman Empire in Europe and the Mediterranean. Trade through the overland caravan routes via Asia Minor and the Middle East, though at a relative trickle compared to later times, antedated the southern trade route via the Red Sea and monsoons which started around the beginning of the Common Era (CE) following the reign of Augustus and his conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE.[1]

The southern route so helped enhance trade between the ancient Roman Empire and the Indian subcontinent, that Roman politicians and historians are on record decrying the loss of silver and gold to buy silk to pamper Roman wives, and the southern route grew to eclipse and then totally supplant the overland trade route.[2]

Roman and Greek traders frequented the ancient Tamil country, present day Southern India and Sri Lanka, securing trade with the seafaring Tamil states of the Pandyan, Chola and Chera dynasties and establishing trading settlements which secured trade with the Indian Subcontinent by the Greco-Roman world since the time of the Ptolemaic dynasty[3] a few decades before the start of the Common Era and remained long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.[4] As recorded by Strabo, Emperor Augustus of Rome received at Antioch an ambassador from a South Indian king called Pandyan of Dramira. The country of the Pandyas, Pandi Mandala, was described as Pandyan Mediterranea in the Periplus and Modura Regia Pandyan by Ptolemy.[5] They also outlasted Byzantium's loss of the ports of Egypt and the Red Sea[6] (c. 639–645 CE) under the pressure of the Muslim conquests. Sometime after the sundering of communications between the Axum and Eastern Roman Empire in the 7th century, the Christian kingdom of Axum fell into a slow decline, fading into obscurity in western sources. It survived, despite pressure from Islamic forces, until the 11th century, when it was reconfigured in a dynastic squabble. Communications were reinstated after the Muslim forces retreated.

Background

The Seleucid dynasty controlled a developed network of trade with the Indian Subcontinent which had previously existed under the influence of the Achaemenid Empire. The Greek-Ptolemaic dynasty, controlling the western and northern end of other trade routes to Southern Arabia and the Indian Subcontinent,[7] had begun to exploit trading opportunities in the region prior to the Roman involvement but, according to the historian Strabo, the volume of commerce between Indians and the Greeks was not comparable to that of later Indo-Roman trade.[2]

The Periplus Maris Erythraei mentions a time when sea trade between Egypt and the subcontinent did not involve direct sailings.[2] The cargo under these situations was shipped to Aden:[2]

Aden – Arabia Eudaimon was called the fortunate, being once a city, when, because ships neither came from India to Egypt nor did those from Egypt dare to go further but only came as far as this place, it received the cargoes from both, just as Alexandria receives goods brought from outside and from Egypt.— Gary Keith Young, Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy

The Ptolemaic dynasty had developed trade with Indian kingdoms using the Red Sea ports.[1] With the establishment of Roman Egypt, the Romans took over and further developed the already existing trade using these ports.[1]

Classical geographers such as Strabo and Pliny the Elder were generally slow to incorporate new information into their works and, from their positions as esteemed scholars, were seemingly prejudiced against lowly merchants and their topographical accounts.[8] Ptolemy's Geography represents somewhat of a break from this since he demonstrated an openness to their accounts and would not have been able to chart the Bay of Bengal so accurately had it not been for the input of traders.[8] It is perhaps no surprise then that Marinus and Ptolemy relied on the testimony of a Greek sailor named Alexander for how to reach "Cattigara" (most likely Oc Eo, Vietnam, where Antonine-period Roman artefacts have been discovered) in the Magnus Sinus (i.e. Gulf of Thailand and South China Sea) located east of the Golden Chersonese (i.e. Malay Peninsula).[9][10] In the 1st-century CE Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, its anonymous Greek-speaking author, a merchant of Roman Egypt, provides such vivid accounts of trade cities in Arabia and India, including travel times from rivers and towns, where to drop anchor, the locations of royal courts, lifestyles of the locals and goods found in their markets, and favorable times of year to sail from Egypt to these places in order to catch the monsoon winds, that it is clear he visited many of these locations.[11]

Early Common Era

Prior to Roman expansion, the various peoples of the subcontinent had established strong maritime trade with other countries. The dramatic increase in the importance of Indian ports, however, did not occur until the opening of the Red Sea by the Greeks and the Romans' attainment concerning the region’s seasonal monsoons. The first two centuries of the Common Era indicate a marked increase in trade between western India and the Roman east by sea. Th expansion of trade was made possible by the stability bright to the region by the Roman Empire from the time of Augustus (r. 27 BCE-14 CE) which allowed for new explorations and the creation of a sound silver and gold coinage. .

The west coast of present-day India is mentioned frequently in literature, such as the Periplus Maris Erythraei. The area was noted for its strong tidal currents, turbulent waves and rocky sea-beds were dangerous for shipping experience. The anchors of ships would be caught by the waves and quickly detach to capsize the vessel or cause a shipwreck. Stone anchors have been observed near Bet Dwarka, an island situated in the Gulf of Kachchh, from ship lsot at sea. Onshore and offshore explorations have been carried out around Bet Dwarka Island since 1983. The finds discovered include lead and stone objects buried in sediment and considered to be anchors due to their axial holes. Though it is unlikely that the remains of the shipwreck’s hull survived, offshore explorations in 2000 and 2001 have yielded seven differently-sized amphoras, two lead anchors, forty-two stone anchors of different types, a supply of potsherds, and a circular lead ingot. The remains of the seven amphoras were of a thick, coarse fabric with a rough surface, which was used for exporting wine and olive oil from the Roman Empire. Archeologists have concluded that most of these were wine amphoras, since olive oil was in less demand in the subcontinent.

Since the discoveries at Bet Dwarka are significant for the maritime history of the region, archeologists have researched the resources in India. Despite the unfavorable conditions the island is situated in, the following items have made Bet Dwarka as well as the rest of western India an important place for trade. From Latin literature, Rome imported Indian tigers, rhinoceros, elephants, and serpents to use for circus shows – a method employed as entertainment to prevent riots in Rome. It has been noted in the Periplus that Roman women also wore Indian Ocean pearls and used a supply of herbs, spices, pepper, lyceum, costus, sesame oil and sugar for food. Indigo was used as a color while cotton cloth was used as articles of clothing. Furthermore, the subcontinent exported ebony for fashioned furniture in Rome. The Roman Empire also imported Indian lime, peach, and various other fruits for medicine. Western India, as a result, was the recipient of large amounts of Roman gold during this time.

Since one must sail against the narrow gulfs of western India, special large boats were used and ship development was demanded. At the entrance of the gulf, large ships called trappaga and cotymba helped guide foreign vessels safely to the harbor. These ships were capable of relatively long coastal cruises, and several seals have depicted this type of ship. In each seal, parallel bands were suggested to represent the beams of the ship. In the center of the vessel is a single mast with a tripod base.

Apart from the recent explorations, close trade relations as well as the development of ship building were supported by the discovery of several Roman coins. On these coins were depictions of two strongly constructed masted ships. Thus, these depictions of Indian ships, originating from both coins and literature (Pliny and Pluriplus), indicate Indian development in seafaring due to the increase in Indo-Roman commerce. In addition, the silver Roman coins discovered in western India primarily come from the 1st, 2nd, and 5th centuries. These Roman coins also suggest that the Indian peninsula possessed a stable sea borne trade with Rome during 1st and 2nd century AD. Land routes, during the time of Augustus, were also used for Indian embassies to reach Rome.

The discoveries found on Bet Dwarka and on other areas on the western coast of India strongly indicate that there were strong Indo-Roman trade relations during the first two centuries of the Common Era. The 3rd century, however, was the demise of the Indo-Roman trade. The sea-route between Rome and India was shut down, and as a result, the trading reverted to the time prior to Roman expansion and exploration.

Establishment

The replacement of Greek kingdoms by the Roman empire as the administrator of the eastern Mediterranean basin led to the strengthening of direct maritime trade with the east and the elimination of the taxes extracted previously by the middlemen of various land based trading routes.[12] Strabo's mention of the vast increase in trade following the Roman annexation of Egypt indicates that monsoon was known from his time.[13]

The trade started by Eudoxus of Cyzicus in 130 BCE kept increasing according to Strabo (II.5.12.):[14]

At any rate, when Gallus was prefect of Egypt, I accompanied him and ascended the Nile as far as Syene and the frontiers of Kingdom of Aksum (Ethiopia), and I learned that as many as one hundred and twenty vessels were sailing from Myos Hormos to the subcontinent, whereas formerly, under the Ptolemies, only a very few ventured to undertake the voyage and to carry on traffic in Indian merchandise.— Strabo

By the time of Augustus up to 120 ships were setting sail every year from Myos Hormos to India.[14] So much gold was used for this trade, and apparently recycled by the Kushan Empire (Kushans) for their own coinage, that Pliny the Elder (NH VI.101) complained about the drain of specie to India:[15]

India, China and the Arabian peninsula take one hundred million sesterces from our empire per annum at a conservative estimate: that is what our luxuries and women cost us. For what fraction of these imports is intended for sacrifices to the gods or the spirits of the dead?— Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.[16]

Gold coin of Claudius (50-51 CE) excavated in South India.

Gold coin of Claudius (50-51 CE) excavated in South India. Gold coin of Justinian I (527-565 CE) excavated in India probably in the south.

Gold coin of Justinian I (527-565 CE) excavated in India probably in the south.

Trade of exotic animals

There is evidence of animal trade between Indian Ocean harbours and the Mediterranean. This can be seen in the mosaics and frescoes of the remains of Roman villas in Italy. For example, the Villa del Casale has mosaics depicting the capture of animals in India, Indonesia and Africa. The intercontinental trade of animals was one of the sources of wealth for the owners of the villa. In the Ambulacro della Grande Caccia, the hunting and capture of animals is represented in such detail that it is possible to identify the species. There is a scene that shows a technique to distract a mother tiger with a shimmering ball of glass or mirror in order to take her cubs. Tiger hunting with red ribbons serving as a distraction is also shown. In the mosaic there are also numerous other animals such as rhinoceros, an Indian elephant (recognized from the ears) with his Indian conductor, and the Indian peafowl, and other exotic birds. There are also numerous animals from Africa. Tigers, leopards and Asian and African lions were used in the arenas and circuses. The European lion was already extinct at that time. Probably the last lived in the Balkan Peninsula and were hunted to stock arenas. The birds and monkeys entertained the guests of many villas. Also in the Villa Romana del Tellaro there is a mosaic with a tiger in the jungle attacking a man with Roman clothes, probably a careless hunter. The animals were transported in cages by ship.[17]

Ports

Roman ports

The three main Roman ports involved with eastern trade were Arsinoe, Berenice and Myos Hormos. Arsinoe was one of the early trading centers but was soon overshadowed by the more easily accessible Myos Hormos and Berenice.

Arsinoe

The Ptolemaic dynasty exploited the strategic position of Alexandria to secure trade with the subcontinent.[3] The course of trade with the east then seems to have been first through the harbor of Arsinoe, the present day Suez.[3] The goods from the East African trade were landed at one of the three main Roman ports, Arsinoe, Berenice or Myos Hormos.[18] The Romans repaired and cleared out the silted up canal from the Nile to harbor center of Arsinoe on the Red Sea.[19] This was one of the many efforts the Roman administration had to undertake to divert as much of the trade to the maritime routes as possible.[19]

Arsinoe was eventually overshadowed by the rising prominence of Myos Hormos.[19] The navigation to the northern ports, such as Arsinoe-Clysma, became difficult in comparison to Myos Hormos due to the northern winds in the Gulf of Suez.[20] Venturing to these northern ports presented additional difficulties such as shoals, reefs and treacherous currents.[20]

Myos Hormos and Berenice

Myos Hormos and Berenice appear to have been important ancient trading ports, possibly used by the Pharaonic traders of ancient Egypt and the Ptolemaic dynasty before falling into Roman control.[1]

The site of Berenice, since its discovery by Belzoni (1818), has been equated with the ruins near Ras Banas in Southern Egypt.[1] However, the precise location of Myos Hormos is disputed with the latitude and longitude given in Ptolemy's Geography favoring Abu Sha'ar and the accounts given in classical literature and satellite images indicating a probable identification with Quseir el-Quadim at the end of a fortified road from Koptos on the Nile.[1] The Quseir el-Quadim site has further been associated with Myos Hormos following the excavations at el-Zerqa, halfway along the route, which have revealed ostraca leading to the conclusion that the port at the end of this road may have been Myos Hormos.[1]

Major regional ports

The regional ports of Barbaricum (modern Karachi), Sounagoura (central Bangladesh) Barygaza, Muziris in Kerala, Korkai, Kaveripattinam and Arikamedu on the southern tip of present-day India were the main centers of this trade, along with Kodumanal, an inland city. The Periplus Maris Erythraei describes Greco-Roman merchants selling in Barbaricum "thin clothing, figured linens, topaz, coral, storax, frankincense, vessels of glass, silver and gold plate, and a little wine" in exchange for "costus, bdellium, lycium, nard, turquoise, lapis lazuli, Seric skins, cotton cloth, silk yarn, and indigo".[21] In Barygaza, they would buy wheat, rice, sesame oil, cotton and cloth.[21]

Barigaza

Trade with Barigaza, under the control of the Indo-Scythian Western Satrap Nahapana ("Nambanus"), was especially flourishing:[21]

There are imported into this market-town (Barigaza), wine, Italian preferred, also Laodicean and Arabian; copper, tin, and lead; coral and topaz; thin clothing and inferior sorts of all kinds; bright-colored girdles a cubit wide; storax, sweet clover, flint glass, realgar, antimony, gold and silver coin, on which there is a profit when exchanged for the money of the country; and ointment, but not very costly and not much. And for the King there are brought into those places very costly vessels of silver, singing boys, beautiful maidens for the harem, fine wines, thin clothing of the finest weaves, and the choicest ointments. There are exported from these places spikenard, costus, bdellium, ivory, agate and carnelian, lycium, cotton cloth of all kinds, silk cloth, mallow cloth, yarn, long pepper and such other things as are brought here from the various market-towns. Those bound for this market-town from Egypt make the voyage favorably about the month of July, that is Epiphi.— Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (paragraph 49).

Muziris

Muziris is a lost port city on the south-western coast of India which was a major center of trade in the ancient Tamil land between the Chera kingdom and the Roman Empire.[22] Its location is generally identified with modern-day Cranganore (central Kerala).[23][24] Large hoards of coins and innumerable shards of amphorae found at the town of Pattanam (near Cranganore) have elicited recent archeological interest in finding a probable location of this port city.[22]

According to the Periplus, numerous Greek seamen managed an intense trade with Muziris:[21]

Then come Naura and Tyndis, the first markets of Damirica (Limyrike), and then Muziris and Nelcynda, which are now of leading importance. Tyndis is of the Kingdom of Cerobothra; it is a village in plain sight by the sea. Muziris, of the same Kingdom, abounds in ships sent there with cargoes from Arabia, and by the Greeks; it is located on a river, distant from Tyndis by river and sea five hundred stadia, and up the river from the shore twenty stadia"— The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (53–54)

Arikamedu

The Periplus Maris Erythraei mentions a marketplace named Poduke (ch. 60), which G.W.B. Huntingford identified as possibly being Arikamedu in Tamil Nadu, a centre of early Chola trade (now part of Ariyankuppam), about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from the modern Pondicherry.[25] Huntingford further notes that Roman pottery was found at Arikamedu in 1937, and archeological excavations between 1944 and 1949 showed that it was "a trading station to which goods of Roman manufacture were imported during the first half of the 1st century AD".[25]

Cultural exchanges

The Rome-subcontinental trade also saw several cultural exchanges which had lasting effect for both the civilizations and others involved in the trade. The Ethiopian kingdom of Aksum was involved in the Indian Ocean trade network and was influenced by Roman culture and Indian architecture.[4] Traces of Indian influences are visible in Roman works of silver and ivory, or in Egyptian cotton and silk fabrics used for sale in Europe.[26] The Indian presence in Alexandria may have influenced the culture but little is known about the manner of this influence.[26] Clement of Alexandria mentions the Buddha in his writings and other Indian religions find mentions in other texts of the period.[26]

Han China was perhaps also involved in the Roman trade, with Roman embassies recorded for the years 166, 226, and 284 that allegedly landed in Rinan (Jianzhi) in northern Vietnam, according to Chinese histories.[9][27][28][29] Roman coins and goods such as glasswares and silverwares have been found in China,[30][31] as well as Roman coins, bracelets, glass beads, a bronze lamp, and Antonine-period medallions in Vietnam, especially at Oc Eo (belonging to the Funan Kingdom).[9][27][32] The 1st-century Periplus notes how a country called This, with a great city called Thinae (comparable to Sinae in Ptolemy's Geography), produced silk and exported it to Bactria before it traveled overland to Barygaza in India and down the Ganges River.[33] While Marinus of Tyre and Ptolemy provided vague accounts of the Gulf of Thailand and Southeast Asia,[34] the Alexandrian Greek monk and former merchant Cosmas Indicopleustes, in his Christian Topography (c. 550), spoke clearly about China, how to sail there, and how it was involved in the clove trade stretching to Ceylon.[35][36] Comparing the small amount of Roman coins found in China as opposed to India, Warwick Ball asserts that most of the Chinese silk purchased by the Romans was done so in India, with the land route through ancient Persia playing a secondary role.[37]

Christian and Jewish settlers from Rome continued to live in India long after the decline in bilateral trade.[4] Large hoards of Roman coins have been found throughout India, and especially in the busy maritime trading centers of the south.[4] The Tamilakkam kings reissued Roman coinage in their own name after defacing the coins in order to signify their sovereignty.[38] Mentions of the traders are recorded in the Tamil Sangam literature of India.[38] One such mention reads: "The beautiful warships of the Yavanas came to the prosperous and beautiful Muchiri (Muziris) breaking the white foams of 'Chulli', the big river, and returned with 'curry' (kari, the black pepper) paying for it in gold. (from poem no. 149 of 'Akananuru' of Sangam Literature)"[38]

Decline and aftermath

Roman decline

Trade declined from the mid-3rd century during a crisis period in the Roman Empire but recovered in the 4th century until the early 7th century when Khosrow II Shah of Persian occupied the Roman parts of the Fertile Crescent and Egypt beginning in 614 until defeated by the [39] Eastern Roman emperor Heraclius at the end of 627 after which the lost territories were returned to the Romans.

Destruction of the Gupta Empire by the Hunas

In India, the Alchon Huns invasions (496-534 CE) are said to have seriously damaged India's trade with Europe and Central Asia.[40] The Gupta Empire had been benefiting greatly from Indo-Roman trade. They had been exporting numerous luxury products such as silk, leather goods, fur, iron products, ivory, pearl or pepper from centers such as Nasik, Paithan, Pataliputra or Benares etc. The Huna invasion probably disrupted these trade relations and the tax revenues that came with it.[41]Soon after the invasions, the Gupta Empire, already weakened by these invasions and the rise of local rulers, ended as well.[42] Following the invasions, northern India was left in disarray, with numerous smaller Indian powers emerging after the crumbling of the Guptas.[43]

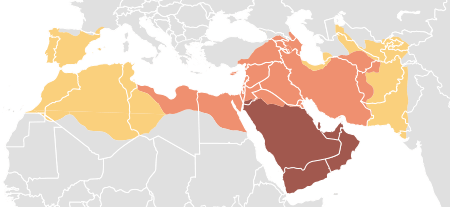

Arab expansion

The Arabs, led by 'Amr ibn al-'As, crossed into Egypt in late 639 or early 640 CE.[44] This advance marked the beginning of the Islamic conquest of Egypt[44]. The capture of Alexandria and the rest of the country ,[6] out an end to 670-year Roman trade with the subcontinent.[3]

Tamil speaking south India turned to Southeast Asia for international trade where Indian culture influenced the native culture to a greater degree than the sketchy impressions made on Rome seen in the adoption of Hinduism and then Buddism [45] However, knowledge of the Indian subcontinent and its trade was preserved in Byzantine books and it is likely that the court of the emperor still maintained some form of diplomatic relation to the region up until at least the time of Constantine VII, seeking an ally against the rising influence of the Islamic states in the Middle East and Persia, appearing in a work on ceremonies called De Ceremoniis.[46]

The Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople in the 15th century (1453), marking the beginning of Turkish control over the most direct trade routes between Europe and Asia.[47] The Ottomans initially cut off eastern trade with Europe, leading in turn to the attempt by Europeans to find a sea route around Africa, spurring the European Age of Discovery, and the eventual rise of European Mercantilism and Colonialism.

See also

- Buddhism and the Roman world

- Chronology of European exploration of Asia

- Indian maritime history

- Sino-Roman relations

- Indo-Roman relations

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Shaw 2003: 426

- 1 2 3 4 Young 2001: 19

- 1 2 3 4 Lindsay 2006: 101

- 1 2 3 4 Curtin 1984: 100

- ↑ The cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia By Edward Balfour

- 1 2 Holl 2003: 9

- ↑ Potter 2004: 20

- 1 2 Parker 2008: 118.

- 1 2 3 Young 2001: 29.

- ↑ Mawer 2013: 38.

- ↑ William H. Schoff (2004) [1912]. Lance Jenott, ed. ""The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century" in The Voyage around the Erythraean Sea". Depts.washington.edu. University of Washington. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ Lach 1994: 13

- ↑ Young 2001: 20

- 1 2 "The Geography of Strabo published in Vol. I of the Loeb Classical Library edition, 1917".

- ↑ "minimaque computatione miliens centena milia sestertium annis omnibus India et Seres et paeninsula illa imperio nostro adimunt: tanti nobis deliciae et feminae constant. quota enim portio ex illis ad deos, quaeso, iam vel ad inferos pertinet?" Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.

- ↑ Original Latin: "minimaque computatione miliens centena milia sestertium annis omnibus India et Seres et paeninsula illa imperio nostro adimunt: tanti nobis deliciae et feminae constant. quota enim portio ex illis ad deos, quaeso, iam vel ad inferos pertinet?

- ↑ "Il Blog sulla Villa Romana del Casale Piazza Armerina". villadelcasale.it. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ↑ O'Leary 2001: 72

- 1 2 3 Fayle 2006: 52

- 1 2 Freeman 2003: 72

- 1 2 3 4 Halsall, Paul. "Ancient History Sourcebook: The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century". Fordham University.

- 1 2 "Search for India's ancient city". BBC. 11 June 2006. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ George Menachery (1987) Kodungallur City of St. Thomas; (2000) Azhikode alias Kodungallur Cradle of Christianity in India

- ↑ "The Telegraph - Calcutta (Kolkata) - Frontpage - Signs of ancient port in Kerala". telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- 1 2 Huntingford 1980: 119.

- 1 2 3 Lach 1994: 18

- 1 2 Ball 2016: 152–3

- ↑ Hill 2009: 27

- ↑ Yule 1915: 53–4

- ↑ An 2002: 83

- ↑ Harper 2002: 99–100, 106–107

- ↑ O'Reilly 2007: 97

- ↑ Schoff 2004 [1912]: paragraph #64. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ↑ Suárez (1999): 90–2

- ↑ Yule 1915: 25–8

- ↑ Lieu 2009: 227

- ↑ Ball 2016: 153–4.

- 1 2 3 Kulke 2004: 108

- ↑ Farrokh 2007: 252

- ↑ The First Spring: The Golden Age of India by Abraham Eraly p.48 sq

- ↑ Longman History & Civics ICSE 9 by Singh p.81

- ↑ Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen p.221

- ↑ A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India p.174

- 1 2 Meri 2006: 224

- ↑ Kulke 2004: 106

- ↑ Luttwak 2009: 167-168

- ↑ The Encyclopedia Americana 1989: 176

References

- An, Jiayao (2002). "When Glass Was Treasured in China". In Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner. Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road. Brepols Publishers. pp. 79–94. ISBN 2-503-52178-9.

- Ball, Warwick (2016). Rome in the East: Transformation of an Empire (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-72078-6.

- Curtin, Philip DeArmond; el al. (1984). Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26931-8.

- The Encyclopedia Americana (1989). Grolier. ISBN 0-7172-0120-1.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2007). Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-108-7.

- Fayle, Charles Ernest (2006). A Short History of the World's Shipping Industry. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28619-0.

- Freeman, Donald B. (2003). The Straits of Malacca: Gateway Or Gauntlet?. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 0-7735-2515-7.

- Harper, P.O. (2002). "Iranian Luxury Vessels in China From the Late First Millennium B.C.E. to the Second Half of the First Millennium C.E.". In Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner. Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road. Brepols Publishers. pp. 95–113. ISBN 2-503-52178-9.

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE. BookSurge. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Holl, Augustin F. C. (2003). Ethnoarchaeology of Shuwa-Arab Settlements. Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0407-1.

- Huntingford, G.W.B. (1980). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Hakluyt Society.

- Kulke, Hermann; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32919-1.

- Lach, Donald Frederick (1994). Asia in the Making of Europe: The Century of Discovery. Book 1. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46731-7.

- Lieu, Samuel N.C. (2009). "Epigraphica Nestoriana Serica". Exegisti monumenta Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams. Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 227–246. ISBN 978-3-447-05937-4.

- Lindsay, W S (2006). History of Merchant Shipping and Ancient Commerce. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0-543-94253-8.

- Luttwak, Edward (2009). The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-03519-4.

- Mawer, Granville Allen (2013). "The Riddle of Cattigara". In Nichols, Robert and Martin Woods. Mapping Our World: Terra Incognita to Australia. National Library of Australia. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9780642278098.

- Meri, Josef W.; Jere L. Bacharach (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96690-6.

- O'Leary, De Lacy (2001). Arabia Before Muhammad. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23188-4.

- O'Reilly, Dougald J.W. (2007). Early Civilizations of Southeast Asia. AltaMira Press, Division of Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-7591-0279-1.

- Parker, Grant (2008). The Making of Roman India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85834-2.

- Potter, David Stone (2004). The Roman Empire at Bay: Ad 180–395. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10058-5.

- Schoff, Williamm H. (2004) [1912]. Lance Jenott, ed. ""The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century" in The Voyage around the Erythraean Sea". Depts.washington.edu. University of Washington. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- Shaw, Ian (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280458-8.

- Young, Gary Keith (2001). Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC-AD 305. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24219-3.

- Yule, Henry (1915). Henri Cordier, ed. Cathay and the Way Thither: Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China, Vol I: Preliminary Essay on the Intercourse Between China and the Western Nations Previous to the Discovery of the Cape Route. 1. Hakluyt Society.

Further reading

- Lionel Casson, The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text With Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Princeton University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-691-04060-5.

- Chami, F. A. 1999. “The Early Iron Age on Mafia island and its relationship with the mainland.” Azania Vol. XXXIV.

- McLaughlin, Raoul. (2010). Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India and China. Continuum, London and New York. ISBN 978-1-84725-235-7.

- Miller, J. Innes. 1969. The Spice Trade of The Roman Empire: 29 B.C. to A.D. 641. Oxford University Press. Special edition for Sandpiper Books. 1998. ISBN 0-19-814264-1.

- Sidebotham, Steven E. (2011). Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24430-6.

- Van der Veen, Marijke (2011). Consumption, Trade and Innovation. Exploring the Botanical Remains from the Roman and Islamic Ports at Quseir al-Qadim, Egypt. Frankfurt: Africa Magna Verlag. ISBN 978-3-937248-23-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indo-Roman trade and relations. |

- English translation of the Periplus Maris Erythraei (Voyage around the Erythraean Sea)

- BBC News: Search for India's ancient city

- Trade between the Romans and the Empires of Asia