Hearing aid

A hearing aid or deaf aid is a device designed to improve hearing. Hearing aids are classified as medical devices in most countries, and regulated by the respective regulations. Small audio amplifiers such as PSAPs or other plain sound reinforcing systems cannot be sold as "hearing aids".

Earlier devices, such as ear trumpets or ear horns,[1][2] were passive amplification cones designed to gather sound energy and direct it into the ear canal. Modern devices are computerised electroacoustic systems that transform environmental sound to make it more intelligible or comfortable, according to audiometrical and cognitive rules. Such sound processing can be considerable, such as highlighting a spatial region, shifting frequencies, cancelling noise and wind, or highlighting voice.

Modern hearing aids require configuration to match the hearing loss, physical features, and lifestyle of the wearer. This process is called "fitting" and is performed by audiologists. The amount of benefit a hearing aid delivers depends in large part on the quality of its fitting. Devices similar to hearing aids include the bone anchored hearing aid, and cochlear implant.

Uses

Hearing aids are incapable of truly correcting a hearing loss; they are an aid to make sounds more accessible. Two primary issues minimize the effectiveness of hearing aids:

- When the primary auditory cortex does not receive regular stimulation, this part of the brain loses cells which process sound. Cell loss increases as the degree of hearing loss increases.

- Damage to the hair cells of the inner ear results in sensorineural hearing loss, which affects the ability to discriminate between sounds. This often manifests as a decreased ability to understand speech, and simply amplifying speech (as a hearing aid does) is often insufficient to improve speech perception.

Adjustment

Hearing aids are incapable of truly correcting a hearing loss; they are an aid to make sounds more accessible. Three primary issues minimize the effectiveness of hearing aids:

- The occlusion effect is a common complaint, especially for new users. Though if the aids are worn regularly, most people will become acclimated after a few weeks. If the effect persists, an audiologist or Hearing Instrument Specialist can sometimes further tune the hearing aid(s).

- The compression effect: The amplification needed to make quiet sounds audible, if applied to loud sounds would damage the inner ear (cochlea). Louder sounds are therefore reduced giving a smaller audible volume range and hence inherent distortion. Hearing protection is also provided by an overall cap to the sound pressure. Also of protective value is impulse noise suppression, available in some high-end aids.

- The initial fitting appointment is rarely sufficient, and multiple follow-up visits are often necessary. Most audiologists or Hearing Instrument Specialists will recommend an up-to-date audiogram at the time of purchase and at subsequent fittings.

Evaluation

There are several ways of evaluating how well a hearing aid compensates for hearing loss. One approach is audiometry which measures a subject's hearing levels in laboratory conditions. The threshold of audibility for various sounds and intensities is measured in a variety of conditions. Although audiometric tests may attempt to mimic real-world conditions, the patient's own every day experiences may differ. An alternative approach is self-report assessment, where the patient reports their experience with the hearing aid.[3][4]

Hearing aid outcome can be represented by three dimensions:[5]

- hearing aid usage

- aided speech recognition

- benefit/satisfaction

The most reliable method for assessing the correct adjustment of a hearing aid is through real ear measurement.[6] Real ear measurements (or probe microphone measurements) are an assessment of the characteristics of hearing aid amplification near the ear drum using a silicone probe tube microphone.[7]

Types

There are many types of hearing aids (also known as hearing instruments), which vary in size, power and circuitry. Among the different sizes and models are:

_Hearing_Aid%2C_Model-A3A%2C_Pastel_Coralite_Case%2C_Bone-Air%2C_Original_Cost_%3D_50.00_USD%2C_Circa_1944_(10840966755).jpg) Vacuum tube hearing aid, circa 1944

Vacuum tube hearing aid, circa 1944_Hearing_Aid%2C_Model_70A%2C_Made_in_the_USA_(12483173304).jpg) Transistor body-worn hearing aid.

Transistor body-worn hearing aid. Pair of BTE hearing aids with earmolds.

Pair of BTE hearing aids with earmolds.- Receiver-in-the-Canal hearing aids

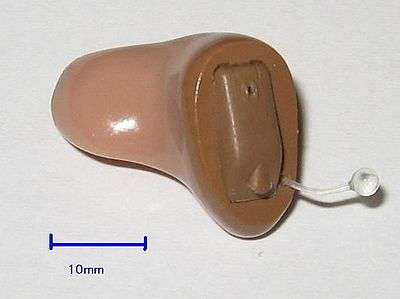

In-the-Ear Hearing Aid

In-the-Ear Hearing Aid In-the-canal hearing aid

In-the-canal hearing aid Completely in the canal hearing aids

Completely in the canal hearing aids- Woman wearing a bone anchored hearing aid

Body worn aids

This was the first type of hearing aid invented by Harvey Fletcher while working at Bell Laboratories.[8] Body aids consist of a case and an earmold, attached by a wire. The case contains the electronic amplifier components, controls and battery while the earmold typically contains a miniature loudspeaker. The case is typically about the size of a pack of playing cards and is carried in a pocket or on a belt.[9] Without the size constraints of smaller hearing devices, body worn aid designs can provide large amplification and long battery life at a lower cost. Body aids are still marketed in emerging markets because of their lower cost.[9]

Behind the ear aids

Behind the ear aids are also called "receiver-in-the-aid" or RITA devices.[10] These devices are useful for people who require significant amplification across many frequencies due to moderate to severe hearing loss.[10] Larger models tend to be easier to handle for changing batteries or configuring controls.[10] The earmolds on these are easier to clean than other sorts of devices, but they also will be more visible and prone to buildup of wax.[10] If the earmold is not vented then that can make the ear feel plugged.[10]

Behind the ear aids (BTE) consist of a case, an earmold or dome and a connection between them. The case contains the electronics, controls, battery, microphone(s) and often the loudspeaker. Generally, the case sits behind the pinna with the connection from the case coming down the front into the ear. The sound from the instrument can be routed acoustically or electrically to the ear. If the sound is routed electrically, the speaker (receiver) is located in the earmold or an open-fit dome, while acoustically coupled instruments use a plastic tube to deliver the sound from the case’s loudspeaker to the earmold.[11] BTEs are also easily connected to assistive listening devices, such as FM systems, to directly integrate sound sources with the instrument. BTE aids are commonly worn by children who need a durable type of hearing aid.[9]

- "Mini" BTE (or "on-the-ear") aids

A new type of BTE aid called the mini BTE (or "on-the-ear") aid. It also fits behind/on the ear, but is smaller. A very thin, almost invisible tube is used to connect the aid to the ear canal. Mini BTEs may have a comfortable ear piece for insertion ("open fit"), but may also use a traditional earmold. Mini BTEs allow not only reduced occlusion or "plugged up" sensations in the ear canal, but also increase comfort, reduce feedback and address cosmetic concerns for many users.[12]

- Receiver in the canal/ear (CRT/RIC/RITE)

In a "receiver in the canal" device, the receiver is the speaker which sends sound into the ear.[10] To fit this device may have either a custom-made mold or a general use dome fitting.[10] Many users find this device to be more comfortable.[10] The larger versions are easier to wear.[10] Disadvantages are that these need to be replaced more often due to moisture and wax damage.[10] Also they have technical limits on how much low frequency amplification they can do.[10]

- BTE Cross System

Cross systems are used for people with hearing loss in one ear or significantly more in one ear, this system allows the user to wear technically a microphone in one ear and the speech is transferred into a speaker in the good ear, whilst the cone in the good ear allow normal hearing

- BTE Bi Cross System

BTE Bi Cross System is the same as the Cross system, however it can also enhance the hearing in the individuals better ear by enhancing the volume of the input, therefore channeling the sound into the good ear, whilst enhancing the clarity and volume for it also

- Earmolds

An earmold is created from an impression taken of the individual's outer ear. This usually ensures a comfortable fit and reduces the possibility of feedback.[9] Earmolds are made from a variety of hard (firm) and soft (pliable) materials. The color of the case and earmold of a BTE aid can be modified and optional decorations can be added.[13]

In the ear aids

In the ear aids (ITE) devices fit in the outer ear bowl (called the concha). Being larger, these are easier to insert and can hold extra features.[10] They are sometimes visible when standing face to face with someone. ITE hearing aids are custom made to fit each individual's ear. They can be used in mild to some severe hearing losses. Feedback, a squealing/whistling caused by sound (particularly high frequency sound) leaking and being amplified again, may be a problem for severe hearing losses.[14] Some modern circuits are able to provide feedback regulation or cancellation to assist with this. Venting may also cause feedback. A vent is a tube primarily placed to offer pressure equalization. However, different vent styles and sizes can be used to influence and prevent feedback.[15] Traditionally, ITEs have not been recommended for young children because their fit could not be as easily modified as the earmold for a BTE, and thus the aid had to be replaced frequently as the child grew.[16] However, there are new ITEs made from a silicone type material that mitigates the need for costly replacements. ITE hearing aids can be connected wirelessly to FM systems, for instance with a body-worn FM receiver with induction neck-loop which transmits the audio signal from the FM transmitter inductively to the telecoil inside the hearing instrument.

Mini in canal (MIC) or completely in canal (CIC) aids are generally not visible unless the viewer looks directly into the wearer's ear.[17][18] These aids are intended for mild to moderately severe losses. CICs are usually not recommended for people with good low-frequency hearing, as the occlusion effect is much more noticeable.[19] Completely-in-the-canal hearing aids fit tightly deep in the ear.[10] It barely visible.[10] Being small, it will not have a directional microphone, and its small batteries will have a short life, and the batteries and controls may be difficult to manage.[10] Its position in the ear prevents wind noise and makes it easier to use phones without feedback.[10] In-the-canal hearing aids are placed deep in the ear canal.[10] They are barely visible.[10] Larger versions of these can have directional microphones.[10] Being in the canal, they are less likely to cause a plugged feeling.[10] These models are easier to manipulate than the smaller completely in-the-canal models but still have the drawbacks of being rather small.[10]

In-the-ear hearing aids are typically more expensive than behind-the-ear counterparts of equal functionality, because they are custom fitted to the patient's ear. In fitting, an audiologist takes a physical impression (mold) of the ear. The mold is scanned by a specialized CAD system, resulting in a 3D model of the outer ear. During modeling, the venting tube is inserted. The digitally modeled shell is printed using a rapid prototyping technique such as stereolithography. Finally, the aid is assembled and shipped to the audiologist after a quality check.[20]

Invisible in canal hearing aids

Invisible in canal hearing aids (IIC) style of hearing aids fits inside the ear canal completely, leaving little to no trace of an installed hearing aid visible. This is because it fits deeper in the canal than other types, so that it is out of view even when looking directly into the ear bowl (concha). A comfortable fit is achieved because the shell of the aid is custom-made to the individual ear canal after taking a mould. Invisible hearing aid types use venting and their deep placement in the ear canal to give a more natural experience of hearing. Unlike other hearing aid types, with the IIC aid the majority of the ear is not blocked (occluded) by a large plastic shell. This means that sound can be collected more naturally by the shape of the ear, and can travel down into the ear canal as it would with unassisted hearing. Depending on their size, some models allow the wearer to use a mobile phone as a remote control to alter memory and volume settings, instead of taking the IIC out to do this. IIC types are most suitable for users up to middle age, but are not suitable for more elderly people.

Extended wear hearing aids

Extended wear hearing aids are hearing devices that are non-surgically placed in the ear canal by a hearing professional. The extended wear hearing aid represents the first "invisible" hearing device. These devices are worn for 1–3 months at a time without removal. They are made of soft material designed to contour to each user and can be used by people with mild to moderately severe hearing loss. Their close proximity to the ear drum results in improved sound directionality and localization, reduced feedback, and improved high frequency gain.[21] While traditional BTE or ITC hearing aids require daily insertion and removal, extended wear hearing aids are worn continuously and then replaced with a new device. Users can change volume and settings without the aid of a hearing professional. The devices are very useful for active individuals because their design protects against moisture and earwax and can be worn while exercising, showering, etc. Because the device’s placement within the ear canal makes them invisible to observers, extended wear hearing aids are popular with those who are self-conscious about the aesthetics of BTE or ITC hearing aid models. As with other hearing devices, compatibility is based on an individual’s hearing loss, ear size and shape, medical conditions, and lifestyle. The disadvantages include regular removal and reinsertion of the device when the battery dies, inability to go underwater, earplugs when showering, and for some discomfort with the fit since it is inserted deeply in the ear canal, the only part of the body where skin rests directly on top of bone.

Open-fit devices

"Open-fit" or "over-the-ear" (OTE) hearing aids are small behind-the-ear type devices. This type is characterized by a minimal amount of effect on the ear canal resonances, as it traditionally leaves the ear canal as open as possible, often only being plugged up by a small speaker resting in the middle of the ear canal space. Traditionally, these hearing aids have a small plastic case behind the ear and a small clear tube running into the ear canal. Inside the ear canal, a small soft silicone dome or a molded, highly vented acrylic tip holds the tube in place. This design is intended to reduce the occlusion effect. Conversely, because of the increased possibility of feedback, and because an open fit allows low frequency sounds to leak out of the ear canal, they are limited to moderately severe high-frequency losses. While the design approach is attractive to a general hearing aid user, open-fit devices can by their design have problems when connected to Assistive Listening Devices (ALD's). This problem has been addressed by manufacturers, who provide assistive listening devices that can be paired with the hearing aid.

Personal, user, self, or consumer programmable

The personal programmable, consumer programmable, consumer adjustable, or self programmable hearing aid allows the consumer to adjust their own hearing aid settings to their own preference using their own PC. Personal programmable hearing aid manufacturers or dealers can also remotely adjust these types of hearing aids for the customer. Available in all hearing aid styles, these hearing aids differ from traditional hearing aids only in that they are adjustable by the consumer.

Disposable hearing aids

Disposable hearing aids are hearing aids that have a non-replaceable battery. These aids are designed to use power sparingly, so that the battery lasts longer than batteries used in traditional hearing aids. Disposable hearing aids are meant to remove the task of battery replacement and other maintenance chores (adjustment or cleanings).

Bone anchored hearing aids

A bone anchored hearing aid (BAHA) is an auditory prosthetic based on bone conduction which can be surgically implanted. It is an option for patients without external ear canals, when conventional hearing aids with a mould in the ear cannot be used. The BAHA uses the skull as a pathway for sound to travel to the inner ear. For people with conductive hearing loss, the BAHA bypasses the external auditory canal and middle ear, stimulating the functioning cochlea. For people with unilateral hearing loss, the BAHA uses the skull to conduct the sound from the deaf side to the side with the functioning cochlea.

Individuals under the age of two (five in the USA) typically wear the BAHA device on a Softband. This can be worn from the age of one month as babies tend to tolerate this arrangement very well. When the child's skull bone is sufficiently thick, a titanium "post" can be surgically embedded into the skull with a small abutment exposed outside the skin. The BAHA sound processor sits on this abutment and transmits sound vibrations to the external abutment of the titanium implant. The implant vibrates the skull and inner ear, which stimulate the nerve fibers of the inner ear, allowing hearing.

The surgical procedure is simple both for the surgeon, involving very few risks for the experienced ear surgeon. For the patient, minimal discomfort and pain is reported. Patients may experience numbness of the area around the implant as small superficial nerves in the skin are sectioned during the procedure. This often disappears after some time. There is no risk of further hearing loss due to the surgery. One important feature of the Baha is that, if a patient for whatever reason does not want to continue with the arrangement, it takes the surgeon less than a minute to remove it. The Baha does not restrict the wearer from any activities such as outdoor life, sporting activities etc.

A BAHA can be connected to an FM system by attaching a miniaturized FM receiver to it.

Two main brands manufacture BAHAs today – the original inventors Cochlear, and the hearing aid company Oticon.

Eyeglass aids

During the late 1950s through 1970s, before in-the-ear aids became common (and in an era when thick-rimmed eyeglasses were popular), people who wore both glasses and hearing aids frequently chose a type of hearing aid that was built into the temple pieces of the spectacles.[22] However, the combination of glasses and hearing aids was inflexible: the range of frame styles was limited, and the user had to wear both hearing aids and glasses at once or wear neither. Today, people who use both glasses and hearing aids can use in-the-ear types, or rest a BTE neatly alongside the arm of the glasses. There are still some specialized situations where hearing aids built into the frame of eyeglasses can be useful, such as when a person has hearing loss mainly in one ear: sound from a microphone on the "bad" side can be sent through the frame to the side with better hearing.

This can also be achieved by using CROS or bi-CROS style hearing aids, which are now wireless in sending sound to the better side.

- Spectacle hearing aids

These are generally worn by people with a hearing loss who either prefer a more cosmetic appeal of their hearing aids by being attached to their glasses or where sound cannot be passed in the normal way, via a hearing aids, perhaps due to a blockage in the ear canal. pathway or if the client suffers from continual infections in the ear. Spectacle aids come in two forms, bone conduction spectacles and air conduction spectacles.

- Bone conduction spectacles

Sounds are transmitted via a receiver attached from the arm of the spectacles which are fitted firmly behind the boney portion of the skull at the back of the ear, (mastoid process) by means of pressure, applied on the arm of the spectacles. The sound is passed from the receiver on the arm of the spectacles to the inner ear (cochlea), via the bony portion. The process of transmitting the sound through the bone requires a great amount of power. Bone conduction aids generally have a poorer high pitch response and are therefore best used for conductive hearing losses or where it is impractical to fit standard hearing aids.

- Air conduction spectacles

Unlike the bone conduction spectacles the sound is transmitted via hearing aids which are attached to the arm or arms of the spectacles. When removing your glasses for cleaning, the hearing aids are detached at the same time. Whilst there are genuine instances where spectacle aids are a preferred choice, they may not always be the most practical option.

- Directional spectacles

These 'hearing glasses' incorporate a directional microphone capability: four microphones on each side of the frame effectively work as two directional microphones, which are able to discern between sound coming from the front and sound coming from the sides or back of the user.[23] This improves the signal-to-noise ratio by allowing for amplification of the sound coming from the front, the direction in which the user is looking, and active noise control for sounds coming from the sides or behind. Only very recently has the technology required become small enough to be fitted in the frame of the glasses. As a recent addition to the market, this new hearing aid is currently available only in the Netherlands and Belgium.[24]

Stethoscope hearing aid

These hearing aids are designed for medical practitioners with hearing loss who use stethoscopes. The hearing aid is built into the speaker of the stethoscope, which amplifies the sound.

Technology

The first electrical hearing aid used the carbon microphone of the telephone and was introduced in 1896. The vacuum tube made electronic amplification possible, but early versions of amplified hearing aids were too heavy to carry around. Miniaturization of vacuum tubes lead to portable models, and after World War II, wearable models using miniature tubes. The transistor invented in 1948 was well suited to the hearing aid application due to low power and small size; hearing aids were an early adopter of transistors. The development of integrated circuits allowed further improvement of the capabilities of wearable aids, including implementation of digital signal processing techniques and programmability for the individual user's needs.

Compatibility with telephones

A hearing aid and a telephone are "compatible" when they can connect to each other in a way that produces clear, easily understood sound. The term "compatibility" is applied to all three types of telephones (wired, cordless, and mobile). There are two ways telephones and hearing aids can connect with each other:

- Acoustically: the sound from the phone's speaker is picked up by the hearing aid's microphone.

- Electromagnetically: the signal inside the phone's speaker is picked up by the hearing aid's "telecoil" or "T-coil", a special loop of wire inside the hearing aid.

Note that telecoil coupling has nothing to do with the radio signal in a cellular or cordless phone: the audio signal picked up by the telecoil is the weak electromagnetic field that is generated by the voice coil in the phone's speaker as it pushes the speaker cone back and forth.

The electromagnetic (telecoil) mode is usually more effective than the acoustic method. This is mainly because the microphone is often automatically switched off when the hearing aid is operating in telecoil mode, so background noise is not amplified. Since there is an electronic connection to the phone, the sound is clearer and distortion is less likely. But in order for this to work, the phone has to be hearing-aid compatible. More technically, the phone's speaker has to have a voice coil that generates a relatively strong electromagnetic field. Speakers with strong voice coils are more expensive and require more energy than the tiny ones used in many modern telephones; phones with the small low-power speakers cannot couple electromagnetically with the telecoil in the hearing aid, so the hearing aid must then switch to acoustic mode. Also, many mobile phones emit high levels of electromagnetic noise that creates audible static in the hearing aid when the telecoil is used. A workaround that resolves this issue on many mobile phones is to plug a wired (not Bluetooth) headset into the mobile phone; with the headset placed near the hearing aid the phone can be held far enough away to attenuate the static. Another method is to use a "neckloop" (which is like a portable, around-the-neck induction loop), and plug the neckloop directly into the standard audio jack (headphones jack) of a smartphone (or laptop, or stereo, etc.). Then, with the hearing aids' telecoil turned on (usually a button to press), the sound will travel directly from the phone, through the neckloop and into the hearing aids' telecoils.[25]

On 21 March 2007, the Telecommunications Industry Association issued the TIA-1083 standard,[26] which gives manufacturers of cordless telephones the ability to test their products for compatibility with most hearing aids that have a T-Coil magnetic coupling mode. With this testing, digital cordless phone manufacturers will be able to inform consumers about which products will work with their hearing aids.[27]

The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) has a ratings scale for compatibility between hearing aids and phones:

- When operating in acoustic (Microphone) mode, the ratings are from M1 (worst) to M4 (best).

- When operating in electromagnetic (Telecoil) mode, the ratings are from T1 (worst) to T4 (best).

The best possible rating is M4/T4 meaning that the phone works well in both modes. Devices rated below M3 are unsatisfactory for people with hearing aids.

Wireless hearing aids

Recent hearing aids include wireless hearing aids. One hearing aid can transmit to the other side so that pressing one aid's program button simultaneously changes the other aid, so that both aids change background settings simultaneously. FM listening systems are now emerging with wireless receivers integrated with the use of hearing aids. A separate wireless microphone can be given to a partner to wear in a restaurant, in the car, during leisure time, in the shopping mall, at lectures, or during religious services. The voice is transmitted wirelessly to the hearing aids eliminating the effects of distance and background noise. FM systems have shown to give the best speech understanding in noise of all available technologies. FM systems can also be hooked up to a TV or a stereo.

2.4 gigahertz Bluetooth connectivity is the most recent innovation in wireless interfacing for hearing instruments to audio sources such as TV streamers or Bluetooth enabled mobile phones. Current hearing aids generally do not stream directly via Bluetooth but rather do so through a secondary streaming device (usually worn around the neck or in a pocket), this bluetooth enabled secondary device then streams wirelessly to the hearing aid but can only do so over a short distance. This technology can be applied to ready-to-wear devices (BTE, Mini BTE, RIE, etc.) or to custom made devices that fit directly into the ear.[28]

In developed countries FM systems are considered a cornerstone in the treatment of hearing loss in children. More and more adults discover the benefits of wireless FM systems as well, especially since transmitters with different microphone settings and Bluetooth for wireless cell phone communication have become available.[29]

Many theatres and lecture halls are now equipped with assistive listening systems that transmit the sound directly from the stage; audience members can borrow suitable receivers and hear the program without background noise. In some theatres and churches FM transmitters are available that work with the personal FM receivers of hearing instruments.

Directional microphones

Most older hearing aids have only an omnidirectional microphone. An omnidirectional microphone amplifies sounds equally from all directions. In contrast, a directional microphone amplifies sounds from one direction more than sounds from other directions. This means that sounds originating from the direction the system is steered toward are amplified more than sounds coming from other directions. If the desired speech arrives from the direction of steering and the noise is from a different direction, then compared to an omnidirectional microphone, a directional microphone provides a better signal to noise ratio. Improving the signal-to-noise ratio improves speech understanding in noise. Directional microphones have been found to be the second best method to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (the best method was an FM system, which locates the microphone near the mouth of the desired talker).[30]

Many hearing aids now have both an omnidirectional and a directional microphone mode. This is because the wearer may not need or desire the noise-reducing properties of the directional microphone in a given situation. Typically, the omnidirectional microphone mode is used in quiet listening situations (e.g. living room) whereas the directional microphone is used in noisy listening situations (e.g. restaurant). The microphone mode is typically selected manually by the wearer. Some hearing aids automatically switch the microphone mode.

Adaptive directional microphones automatically vary the direction of maximum amplification or rejection (to reduce an interfering directional sound source). The direction of amplification or rejection is varied by the hearing aid processor. The processor attempts to provide maximum amplification in the direction of the desired speech signal source or rejection in the direction of the interfering signal source. Unless the user manually temporarily switches to a "restaurant program, forward only mode" adaptive directional microphones frequently amplify the speech of other talkers in a cocktail party type environments, such as restaurants or coffee shops. The presence of multiple speech signals makes it difficult for the processor to correctly select the desired speech signal. Another disadvantage is that some noises often contain characteristics similar to speech, making it difficult for the hearing aid processor to distinguish the speech from the noise. Despite the disadvantages, adaptive directional microphones can provide improved speech recognition in noise[31]

FM systems have been found to provide a better signal to noise ratio even at larger speaker-to-talker distances in simulated testing conditions.[32]

Telecoil

Telecoils or T-coils (from "Telephone Coils"), are a small device installed in a hearing aid or cochlear implant. Audio induction loops generate an electromagnetic field that can be detected by T-coils, allowing audio sources to be directly connected to a hearing aid. The T-coil is intended to help the wearer filter out background noise. They can be used with telephones, FM systems (with neck loops), and induction loop systems (also called "hearing loops") that transmit sound to hearing aids from public address systems and TVs. In the UK and the Nordic countries, hearing loops are widely used in churches, shops, railway stations, and other public places. In the U.S.A., telecoils and hearing loops are gradually becoming more common. Audio induction loops, telecoils and hearing loops are gradually becoming more common also in Slovenia.

A T-coil consists of a metal core (or rod) around which ultra-fine wire is coiled. T-coils are also called induction coils because when the coil is placed in a magnetic field, an alternating electric current is induced in the wire (Ross, 2002b; Ross, 2004). The T-coil detects magnetic energy and transduces (converts) it to electrical energy. In the United States, the Telecommunications Industry Association's TIA-1083 standard, specifies how analog handsets can interact with telecoil devices, to ensure the optimal performance.[33]

Although T-coils are effectively a wide-band receiver, interference is unusual in most hearing loop situations. Interference can manifest as a buzzing sound, which varies in volume depending on the distance the wearer is from the source. Sources are electromagnetic fields, such as CRT computer monitors, older fluorescent lighting, some dimmer switches, many household electrical appliances and airplanes.

The states of Florida and Arizona have passed legislation that requires hearing professionals to inform patients about the usefulness of telecoils.

Legislation affecting use

In the United States, the Hearing Aid Compatibility Act of 1988 requires that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ensure that all telephones manufactured or imported for use in the United States after August 1989, and all "essential" telephones, be hearing aid-compatible (through the use of a telecoil).[34]

"Essential" phones are defined as "coin-operated telephones, telephones provided for emergency use, and other telephones frequently needed for use by persons using such hearing aids." These might include workplace telephones, telephones in confined settings (like hospitals and nursing homes), and telephones in hotel and motel rooms. Secure telephones, as well as telephones used with public mobile and private radio services, are exempt from the HAC Act. "Secure" phones are defined as "telephones that are approved by the U.S. Government for the transmission of classified or sensitive voice communications."

In 2003, the FCC adopted rules to make digital wireless telephones compatible with hearing aids and cochlear implants. Although analog wireless phones do not usually cause interference with hearing aids or cochlear implants, digital wireless phones often do because of electromagnetic energy emitted by the phone's antenna, backlight, or other components. The FCC has set a timetable for the development and sale of digital wireless telephones that are compatible with hearing aids. This effort promises to increase the number of digital wireless telephones that are hearing aid-compatible.

Direct audio input

Direct audio input (DAI) allows the hearing aid to be directly connected to an external audio source like a CD player or an assistive listening device (ALD). By its very nature, DAI is susceptible to far less electromagnetic interference, and yields a better quality audio signal as opposed to using a T-coil with standard headphones. An audio boot is a type of device that may be used to facilitate DAI.[35]

Processing

Every electronic hearing aid has at minimum a microphone, a loudspeaker (commonly called a receiver), a battery, and electronic circuitry. The electronic circuitry varies among devices, even if they are the same style. The circuitry falls into three categories based on the type of audio processing (analog or digital) and the type of control circuitry (adjustable or programmable).

- Analog audio

- Adjustable control: The audio circuit is analog with electronic components that can be adjusted. The hearing professional determines the gain and other specifications required for the wearer, and then adjusts the analog components either with small controls on the hearing aid itself or by having a laboratory build the hearing aid to meet those specifications. After the adjustment the resulting audio does not change any further, other than overall loudness that the wearer adjusts with a volume control. This type of circuitry is generally the least flexible. The first practical electronic hearing aid with adjustable analog audio circuitry was based on US Patent 2,017,358, "Hearing Aid Apparatus and Amplifier" by Samual Gordon Taylor, filed in 1932.

- Programmable control: The audio circuit is analog but with additional electronic control circuitry that can be programmed by an audiologist, often with more than one program.[36] The electronic control circuitry can be fixed during manufacturing or in some cases, the hearing professional can use an external computer temporarily connected to the hearing aid to program the additional control circuitry. The wearer can change the program for different listening environments by pressing buttons either on the device itself or on a remote control or in some cases the additional control circuitry operates automatically. This type of circuitry is generally more flexible than simple adjustable controls. The first hearing aid with analog audio circuitry and automatic digital electronic control circuitry was based on US Patent 4,025,721, "Method of and means for adaptively filtering near-stationary noise from speech" by D Graupe, GD Causey, filed in 1975. This digital electronic control circuitry was used to identify and automatically reduce noise in individual frequency channels of the analog audio circuits and was known as the Zeta Noise Blocker.

- Digital audio, programmable control: Both the audio circuit and the additional control circuits are fully digital. The hearing professional programs the hearing aid with an external computer temporarily connected to the device and can adjust all processing characteristics on an individual basis. Fully digital circuitry allows implementation of many additional features not possible with analog circuitry, can be used in all styles of hearing aids and is the most flexible; for example, digital hearing aids can be programmed to amplify certain frequencies more than others, and can provide better sound quality than analog hearing aids. Fully digital hearing aids can be programmed with multiple programs that can be invoked by the wearer, or that operate automatically and adaptively. These programs reduce acoustic feedback (whistling), reduce background noise, detect and automatically accommodate different listening environments (loud vs soft, speech vs music, quiet vs noisy, etc.), control additional components such as multiple microphones to improve spatial hearing, transpose frequencies (shift high frequencies that a wearer may not hear to lower frequency regions where hearing may be better), and implement many other features. Fully digital circuitry also allows control over wireless transmission capability for both the audio and the control circuitry. Control signals in a hearing aid on one ear can be sent wirelessly to the control circuitry in the hearing aid on the opposite ear to ensure that the audio in both ears is either matched directly or that the audio contains intentional differences that mimic the differences in normal binaural hearing to preserve spatial hearing ability. Audio signals can be sent wirelessly to and from external devices through a separate module, often a small device worn like a pendant and commonly called a “streamer”, that allows wireless connection to yet other external devices. This capability allows optimal use of mobile telephones, personal music players, remote microphones and other devices. With the addition of speech recognition and internet capability in the mobile phone, the wearer has optimal communication ability in many more situations than with hearing aids alone. This growing list includes voice activated dialing, voice activated software applications either on the phone or on the internet, receipt of audio signals from databases on the phone or on internet, or audio signals from television sets or from global positioning systems. The first practical, wearable, fully digital hearing aid was invented by Maynard Engebretson, Robert E Morley, Jr. and Gerald R Popelka.[37] Their work resulted in US Patent 4,548,082, "Hearing aids, signal supplying apparatus, systems for compensating hearing deficiencies, and methods" by A Maynard Engebretson, Robert E Morley, Jr. and Gerald R Popelka, filed in 1984. This patent formed the basis of all subsequent fully digital hearing aids from all manufacturers, including those produced currently.

History

The first hearing aids were ear trumpets, and were created in the 17th century. Some of the first hearing aids were external hearing aids. External hearing aids directed sounds in front of the ear and blocked all other noises. The apparatus would fit behind or in the ear.

The movement toward modern hearing aids began with the creation of the telephone, and the first electric hearing aid, the "akouphone," was created about 1895 by Miller Reese Hutchison. By the late 20th century, digital hearing aids were commercially available.[38]

The invention of the carbon microphone, transmitters, digital signal processing chip or DSP, and the development of computer technology helped transform the hearing aid to its present form.[39]

Regulation

Ireland

Like much of the Irish health care system, hearing aid provision is a mixture of public and private.

Hearing aids are provided by the State to children, OAPs and to people whose income is at or below that of the State Pension. The Irish State hearing aid provision is extremely poor; people often have to wait for two years for an appointment.

It is estimated that the total cost to the State, of supplying one hearing aid, exceeds €2,000.

Hearing aids are also available privately, and there is grant assistance available for insured workers. Currently for the fiscal year ending 2016, the grant stands at a maximum of €500 per ear.[40]

Irish taxpayers can also claim tax relief, at the standard rate, as hearing aids are recognised as a medical device.

Hearing aids in the Republic of Ireland are exempt from VAT.

Hearing aid providers in Ireland mostly belong to the Irish Society of Hearing Aid Audiologists.

United States

Ordinary hearing aids are Class I regulated medical devices under Federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rules.[41] A 1976 statute explicitly prohibits any state requirement that is "different from, or in addition to, any requirement applicable" to regulated medical devices (which includes hearing aids) which relates "to the safety and effectiveness of the device."[42] Inconsistent state regulation is preempted under the federal law.[43] In the late 1970s, the FDA established federal rules governing hearing aid sales,[44] and addressed various requests by state authorities for exemptions from federal preemption, granting some and denying others.[45]

Cost

Several industrialized countries supply free or heavily discounted hearing aids through their publicly funded health care system.

Australia

The Australian Department of Health and Ageing provides eligible Australian citizens and residents with a basic hearing aid free-of-charge, though recipients can pay a "top up" charge if they wish to upgrade to a hearing aid with more or better features. Maintenance of these hearing aids and a regular supply of batteries is also provided, on payment of a small annual maintenance fee.[46]

Canada

In Canada, health care is a responsibility of the provinces. In the province of Ontario, the price of hearing aids is partially reimbursed through the Assistive Devices Program of the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, up to $500 for each hearing aid. Like eye appointments, audiological appointments are no longer covered through the provincial public health plan. Audiometric testing can still easily be obtained, often free of charge, in private sector hearing aid clinics and some ear, nose and throat doctors offices. Hearing aids may be covered to some extent by private insurance or in some cases through government programs such as Veterans Affairs Canada or Workplace Safety & Insurance Board.

Iceland

Social Insurance pays a one time fee of ISK 30,000 for any kind of hearing aid. However, the rules are complicated and require that both ears have a significant hearing loss in order to qualify for reimbursement. BTE hearing aids range from ISK 60,000 to ISK 300,000.[47]

India

In India hearing aids of all kinds are easily available. Under Central and state government health services, the poor can often avail themselves of free hearing devices. However, market prices vary for others and can range from Rs 1,000 to Rs 275,000 per ear.

United Kingdom

From 2000 to 2005 the Department of Health worked with Action on Hearing Loss (then called RNID) to improve the quality of NHS hearing aids so every NHS audiology department in England was fitting digital hearing aids by March 2005. By 2003 Over 175,000 NHS digital hearing aids had been fitted to 125,000 people. Private companies were recruited to enhance the capacity, and two were appointed – David Ormerod Hearing Centres, partly owned by Alliance Boots and Ultravox Group, a subsidiary of Amplifon.[48]

Within the United Kingdom, the NHS provides digital BTE hearing aids to NHS patients, on long-term loan, free of charge. Other than BAHAs (Bone anchored hearing aid), where specifically required, BTEs are usually the only style available. Private purchases may be necessary if a user desires a different style. Batteries are free.[49]

In 2014 the Clinical Commissioning Group in North Staffordshire considered proposals to end provision of free hearing aids for adults with mild to moderate age related hearing loss, which currently cost them £1.2m a year. Action on Hearing Loss mobilised a campaign against the proposal.[50]

United States

Most private healthcare providers in the United States do not provide coverage for hearing aids, so all costs are usually borne by the recipient. The cost for a single hearing aid can vary between $500 and $6,000 or more, depending on the level of technology and whether the clinician bundles fitting fees into the cost of the hearing aid. Though if an adult has a hearing loss which substantially limits major life activities, some state-run vocational rehabilitation programs can provide upwards of full financial assistance. Severe and profound hearing loss often falls within the "substantially limiting" category.[51] Less expensive hearing aids can be found on the internet or mail order catalogs, but most in the under-$200 range tend to amplify the low frequencies of background noise, making it harder to hear the human voice.[52][53]

Military Veterans receiving VA medical care are eligible for hearing aids based on medical need. The Veterans Administration pays the full cost of testing and hearing aids to qualified military Veterans. Major VA medical facilities provide complete diagnostic and audiology services.

The cost of hearing aids is a tax-deductible medical expense for those who itemize medical deductions.[54]

Batteries

While there are some instances that a hearing aid uses a rechargeable battery or a long-life disposable battery, the majority of modern hearing aids use one of five standard button cell zinc–air batteries. (Older hearing aids often used mercury battery cells, but these cells have become banned in most countries today.) Modern hearing aid button cell types are typically referred to by their common number name or the color of their packaging.

They are typically loaded into the hearing aid via a rotating battery door, with the flat side (case) as the positive terminal (cathode) and the rounded side as the negative terminal (anode).

These batteries all operate from 1.35 to 1.45 volts.

The type of battery a specific hearing aid utilizes depends on the physical size allowable and the desired lifetime of the battery, which is in turn determined by the power draw of the hearing aid device. Typical battery lifetimes run between 1 and 14 days (assuming 16-hour days).

| Type/ Color Code | Dimensions (Diameter×Height) | Common Uses | Standard Names | Misc Names |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 675 | 11.6 mm × 5.4 mm | High-Power BTEs, Cochlear Implants | IEC: PR44, ANSI: 7003ZD | 675, 675A, 675AE, 675AP, 675CA, 675CP, 675HP, 675HPX, 675 Implant Plus, 675P (HP), 675PA, 675SA, 675SP, A675, A675P, AC675, AC675E, AC675E/EZ, AC675EZ, AC-675E, AP675, B675PA, B6754, B900PA, C675, DA675, DA675H, DA675H/N, DA675N, DA675X, H675AE, L675ZA, ME9Z, P675, P675i+, PR44, PR44P, PR675, PR675H, PR675P, PR-675PA, PZ675, PZA675, R675ZA, S675A, V675, V675A, V675AT, VT675, XL675, Z675PX, ZA675, ZA675HP |

| 13 | 7.9 mm × 5.4 mm | BTEs, ITEs | IEC: PR48, ANSI: 7000ZD | 13, 13A, 13AE, 13AP, 13HP, 13HPX, 13P, 13PA, 13SA, 13ZA, A13, AC13, AC13E, AC13E/EZ, AC13EZ, AC-13E, AP13, B13BA, B0134, B26PA, CP48, DA13, DA13H, DA13H/N, DA13N, DA13X, E13E, L13ZA, ME8Z, P13, PR13, PR13H, PR-13PA, PZ13, PZA13, R13ZA, S13A, V13A, VT13, V13AT, W13ZA, XL13, ZA13 |

| 312 | 7.9 mm × 3.6 mm | miniBTEs, RICs, ITCs | IEC: PR41, ANSI: 7002ZD | 312, 312A, 312AE, 312AP, 312HP, 312HPX, 312P, 312PA, 312SA, 312ZA, AC312, AC312E, AC312E/EZ, AC312EZ, AC-312E, AP312, B312BA, B3124, B347PA, CP41, DA312, DA312H, DA312H/N, DA312N, DA312X, E312E, H312AE, L312ZA, ME7Z, P312, PR312, PR312H, PR-312PA, PZ312, PZA312, R312ZA, S312A, V312A, V312AT, VT312, W312ZA, XL312, ZA312 |

| 10 | 5.8 mm × 3.6 mm | CICs, RICs | IEC: PR70, ANSI: 7005ZD | 10, 10A, 10AE, 10AP, 10DS, 10HP, 10HPX, 10SA, 10UP, 20PA, 230, 230E, 230EZ, 230HPX, AC10, AC10EZ, AC10/230, AC10/230E, AC10/230EZ, AC230, AC230E, AC230E/EZ, AC230EZ, AC-230E, AP10, B0104, B20BA, B20PA, CP35, DA10, DA10H, DA10H/N, DA10N, DA230, DA230/10, L10ZA, ME10Z, P10, PR10, PR10H, PR230H, PR536, PR-10PA, PR-230PA, PZA230, R10ZA, S10A, V10, VT10, V10AT, V10HP, V230AT, W10ZA, XL10, ZA10 |

| 5 | 5.8 mm × 2.1 mm | CICs | IEC: PR63, ANSI: 7012ZD | 5A, 5AE, 5HPX, 5SA, AC5, AC5E, AP5, B7PA, CP63, CP521, L5ZA, ME5Z, P5, PR5H, PR-5PA, PR521, R5ZA, S5A, V5AT, VT5, XL5, ZA5 |

See also

- Ear trumpet

- Electronic nose

- El Deafo ( Cece Bell novel)

- Orkney Wireless Museum – has a 1930s Ardent hearing aid in its collection

- Sonotone 1010 – first electronic hearing aid to use a transistor

- Spatial hearing loss

References

- ↑ Bentler Ruth A., Duve, Monica R. (2000). "Comparison of Hearing Aids Over the 20th Century". Ear & Hearing. 21 (6): 625–639. doi:10.1097/00003446-200012000-00009.

- ↑ "Ear Horn Q&A". Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ↑ Bentler, R. A.; Kramer, S. E. (2000). "Guidelines for choosing a self-report outcome measure". Ear and hearing. 21 (4 Suppl): 37S–49S. PMID 10981593. doi:10.1097/00003446-200008001-00006.

- ↑ Taylor, Brian (22 October 2007). "Self-Report Assessment of Hearing Aid Outcome – An Overview". AudiologyOnline. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ Humes, Larry E. and Humes, Lauren E. (2004). "Factors Affecting Long-Term Hearing Aid Success". Seminars in Hearing. 25 (1): 63–72. doi:10.1055/s-2004-823048.

- ↑ Katz, Jack; Medwetsky, Larry; Burkard, Robert; Hood, Linda (2009). "Chapter 38, Hearing Aid Fitting for Adults: Selection, Fitting, Verification, and Validation". Handbook of Clinical Audiology (6th ed.). Baltimore MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 858. ISBN 978-0-7817-8106-0.

- ↑ Stach, Brad (2003). Comprehensive Dictionary of Audiology (2nd ed.). Clifton Park NY: Thompson Delmar Learning. p. 167. ISBN 1-4018-4826-5.

- ↑ Hartmann, William M. (14 September 2004). Signals, Sound, and Sensation. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-1-56396-283-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Hearing Aid Basics, National Institute of Health, retrieved 2 December 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 "Hearing Aid Buying Guide". Consumer Reports. February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ↑ "Hearing Aids". National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ↑ "Types of Hearing Aids". Food And Drug Administration. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ↑ "Introduction to Ear Molds". HealthyHearing. 23 June 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "Problems with hearing aids: Ask our audiologist – Action On Hearing Loss: RNID". Action On Hearing Loss. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ↑ Sickel, K. (13 September 2007) Shortest Path Search with Constraints on Surface Models of In-ear Hearing Aids 52. IWK, Internationales Wissenschaftliches Kolloquium (Computer science meets automation Ilmenau 10.) Vol. 2 Ilmenau : TU Ilmenau Universitätsbibliothek 2007, pp. 221–226

- ↑ "Hearing Aids for Children". Hearing Aids for Children. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ Eisenberg, Anne (24 September 2005) The Hearing Aid as Fashion Statement. NY Times.

- ↑ Dybala, Paul (6 March 2006) ELVAS Sightings – Hearing Aid or Headset. AudiologyOnline.com.

- ↑ Ross, Mark (January 2004) The "Occlusion Effect" – What it is, and What to Do About it, hearingresearch.org.

- ↑ Sickel, K. et al. (2009) "Semi-Automatic Manufacturing of Customized Hearing Aids Using a Feature Driven Rule-based Framework". Proceedings of the Vision, Modeling, and Visualization Workshop 2009 (Braunschweig, Germany 16–18 November 2009), pp. 305–312

- ↑ Sanford, Mark J., MS; Anderson, Tamara; Sanford, Christine (10 March 2014). "The Extended-Wear Hearing Device: Observations on Patient Experiences and Its Integration into a Practice". The Hearing Review. 24 (3): 26–31. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ "Concealed Hearing Devices of the 20th Century". Concealed Hearing Devices of the 20th Century. Bernard Becker Medical Library. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ Netherlands: Dutch Unveil 'Varibel' – The Eyeglasses That Hear, Publish Date: 1 March 2007, Related Company Website: www, varibel.nl. Accessed 10 February 2008.

- ↑ The manufacturer's website is published in Dutch and French at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 2016-02-09. and there is a TV news report in English at http://varibel.nl/site/Files/default.asp?iChannel=4&nChannel=Files Archived 22 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Mestayer, Kathi. "Staff Writer". Hearing Health Magazine. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ↑ TIA-1083 Revision A, November 17, 2010. ihs.com

- ↑ "New TIA Standard Will Improve Hearing Aid Compatibility with Digital Cordless Phones". U.S. Telecommunications Industry Association. 5 April 2007. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ↑ Mroz, Mandy. "Hearing Aids and Bluetooth Technology". Hearing Aids and Bluetooth Technology. Healthy Hearing. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ↑ Dave Fabry; Hans Mülder; Evert Dijkstra (November 2007). "Acceptance of the wireless microphone as a hearing aid accessory for adults". The Hearing Journal. 60 (11): 32–36. doi:10.1097/01.hj.0000299170.11367.24.

- ↑ Hawkins D (1984). "Comparisons of speech recognition in noise by mildly-to-moderately hearing-impaired children using hearing aids and FM systems". Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 49 (4): 409. doi:10.1044/jshd.4904.409.

- ↑ Ricketts T.; Henry P. (2002). "Evaluation of an adaptive, directional-microphone hearing aid". International Journal of Audiology. 41 (2): 100–112. doi:10.3109/14992020209090400.

- ↑ Lewis, M. Samantha; Crandell, Carl C.; Valente, Michael; Horn, Jane Enrietto (2004). "Speech perception in noise: directional microphones versus frequency modulation (FM) systems". Journal of the American Academy of Audiology. 15 (6): 426–439. doi:10.3766/jaaa.15.6.4.

- ↑ TIA-1083: A NEW STANDARD TO IMPROVE CORDLESS PHONE USE FOR HEARING AID WEARERS. U.S. Telecommunications Industry Association

- ↑ "Public Law 100-394, [47 USC 610] – Hearing Aid Compatibility Act of 1988". PRATP. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ↑ "Boot Definition". www.nchearingloss.org. Retrieved 2017-06-02.

- ↑ Heidtman, Laurel (28 September 2010). "Analog Vs. Digital Hearing Aids". LiveStrong.com. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ↑ Levitt, Harry (26 December 2007). "Digital Hearing Aids". The Asha Leader. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ↑ Mills, Mara (2011). "Hearing Aids and the History of Electronics Miniaturization". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 33 (2): 24. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2011.43.

- ↑ Howard, Alexander (26 November 1998). "Hearing Aids: Smaller and Smarter." New York Times.

- ↑ "Aural". Ireland Department of Social Protection. Retrieved 23 July 2012.

- ↑ 21 U.S.C. § 360k (a) (2005)

- ↑ 21 U.S.C. 5 360k (a) (2005)

- ↑ Missouri Board of Examiners for Hearing Instrument Specialists v. Hearing Help Express, Inc., 447 3d 1033 (8th Cir. 2006)

- ↑ Final Rule issued in Docket 76N-0019, 42 Fed. Reg. 9286 (15 February 1977).

- ↑ Exemption from Preemption of State and Local Hearing Aid Requirements; Applications for Exemption, Docket No. 77N-0333, 45 Fed. Reg. 67326; Medical Devices: Applications for Exemption from Federal Preemption of State and Local hearing Aid Requirements, Docket No. 78P-0222, 45 Fed. 67325 (10 October 1980).

- ↑ "Understanding the Australian Government Hearing Services Program". Archived from the original on 9 September 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ↑ Social Insurance Administration – Iceland Accessed 30 November 2007 Archived 16 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Loud and clear". Health Service Journal. 18 December 2003. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ↑ NHS hearing aid service fact sheet Accessed 26 November 2007 Archived 2 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Hearing aid charging opposed in feedback exercise". Health Service Journal. 23 September 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ↑ The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission: Questions and Answers about Deafness and Hearing Impairments in the Workplace and the Americans with Disabilities Act Accessed 26 November 2007

- ↑ Now Hear This. Chicago Tribune (9 March 2011)

- ↑ Romano, Tricia (22 October 2012) The Hunt for an Affordable Hearing Aid. New York Times

- ↑ Topic 502 – Medical and Dental Expenses Accessed 26 November 2007

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hearing aids. |

- NIH Information from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

- American Hearing Research Foundation funds research in hearing and aims to help educate the public in the United States.

- Royal National Institute for Deaf Information and resources about hearing loss.

- Consumer Reports July 2009 independent survey of hearing aid marketplace

- Historical