Imperial and Royal Aviation Troops

| Imperial and Royal Aviation Troops | |

|---|---|

|

An Oeffag built Albatros D.III flown by Godwin Brumowski (the man on the left) | |

| Active | 1893–1918 |

| Country |

|

| Size | 5431 aircraft produced for the KuKLFT |

| Engagements | World War I |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Emil Uzelac Conrad von Hötzendorf |

| Insignia | |

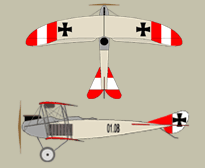

| National Markings |

|

| Tail Markings |

|

| Aircraft flown | |

| Bomber | Hansa-Brandenburg G.I |

| Fighter |

Aviatik D.I Phönix D.I |

| Reconnaissance | Hansa-Brandenburg C.I |

The Imperial and Royal Aviation Troops (Kaiserliche und Königliche Luftfahrtruppen or K.u.K. Luftfahrtruppen) was the air force of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire until the empire's demise in 1918. It saw combat on both the Eastern Front and Italian Front during World War I.

History

.png)

The Air Service began in 1893 as a balloon corps (Militär-Aeronautische Anstalt) and would later be re-organized in 1912 under the command of Major Emil Uzelac, an army engineering officer. The Air Service would remain under his command until the end of World War I in 1918. The first officers of the air force were private pilots with no prior military aviation training.

At the outbreak of war, the Air Service was composed of 10 observation balloons, 85 pilots, and 39 operable aircraft.[1] By the end of 1914, they managed to have 147 operational aircraft deployed in 14 units.[2] Just as Austria-Hungary fielded a joint army and navy, they also had army and naval aviation arms.[3] The latter operated seaplanes;[4] Gottfried Freiherr von Banfield became an ace in one.[5] The Adriatic Coast seaplane stations also hosted bombers. Lohners were the most common variant; however, the K Series heavy bombers mounted a successful offensive against the Italians that suffered few casualties.[6]

Austro-Hungarian pilots and aircrew originally faced off against the air forces of Romania and Russia, while also fielding air units in Serbia, Albania, and Montenegro. Only the Imperial Russian Air Service posed a credible threat, although its wartime production of 4,700 air frames gave it no logistical edge over the Luftfahrtruppen before the IRAS ceased operations in mid-1917.[7] Nevertheless, the Austro-Hungarians requested, and received, aerial reinforcements from their German allies, especially in Galicia.[8]

On 30 September 1915, troops of the Serbian Army observed three Austro-Hungarian aircraft approaching Kragujevac. Soldiers shot at them with shotguns and machine-guns but failed to prevent them from dropping 45 bombs over the city, hitting military installations, the railway station and many other, mostly civilian, targets in the city. During the bombing raid, private Radoje Ljutovac fired his cannon at the enemy aircraft and successfully shot one down. It crashed in the city and both pilots died from their injuries. The cannon Ljutovac used was not designed as an anti-aircraft gun, it was a slightly modified Turkish cannon captured during the First Balkan War in 1912. This was the first occasion in military history that a military aircraft was shot down with artillery ground-to-air fire.

Italy's entry into the war on 15 May 1915 opened another front and brought the Empire's greatest opponent into the air war.[9] The new front was in the southern Alps, making for hazardous flying and near-certain death to any aviators crash-landing in the mountains.[10] To remedy Italy's initial shortage of fighter planes, France posted a squadron to defend Venice and oppose the Austro-Hungarians.[11]

The 1916 Austro-Hungarian aviation program called for expansion to 48 squadrons by year's end; however, only 37 were activated in time. Two-seater reconnaissance and bomber squadrons often had a number of single-seat fighters integrated into the unit to serve as escorts on missions.[12] This reflected the army high command's emphasis on tying fighters to defensive duty.[13]

During 1917, Austria-Hungary pushed its number of flying training schools to 14, with 1,134 trainees. The expansion program was stretched to 68 squadrons, and the Air Service managed to activate the 31 units needed. Nevertheless, the Luftfahrtruppen began to lose its Italian campaign as Italian superior numbers began to tell. By 19 June 1917, the situation had deteriorated to the point where an Italian attack force of 61 bombers and 84 escorting planes was opposed by an Austro-Hungarian defense of only 3 fighters and 23 two-seaters. Within two months, the Luftfahrtruppen found itself facing over 200 enemy aircraft every day. Some of the disparity can be explained by the importation of four squadrons of the Royal Flying Corps to augment the Italian fighter force in the wake of the Battle of Caporetto. Then, when winter came on, shortages of coal and other crucial supplies further hampered production for the Empire's Air Service.[14]

Austro-Hungarian plans for 1918 called for ramping up its aerial force to 100 squadrons containing 1,000 pilots. Production climbed to 2,378 aircraft for the year.[15] However, withdrawal of German air units to fight in France worsened the Austro-Hungarians' shortage of aircraft.[16] By June 1918, the Luftfahrtruppen's strength peaked at 77 Fliks; only 16 were fighter squadrons. By 26 October, a fighter mass of some 400 Italian, British, and French airplanes attacked in the air even as Italian ground forces pushed for victory.[17] The attrited Austro-Hungarians could only launch 29 airplanes in opposition.[18] The local armistice on 3 November 1918 was the effective end of the Luftfahrtruppen, as its parent nation passed into history.[19]

Luftfahrtruppen strength had peaked at only 550 aircraft during the war, despite having four fronts to cover. Its wartime losses amounted to 20 percent of its naval fliers killed in action or accident, and 38 percent of its army aviators.[20]

Aircraft

The aircraft employed by the Air Service were a combination of Austro-Hungarian designs built within the empire, German models that were domestically manufactured by Austrian firms (often with modifications), and planes that were imported from Germany. These aircraft included:

- Etrich Taube

- Etrich Luft-Limousine

- Lohner Type AA

- Lohner L

- Lohner B.VII

- Lohner C.I

- Fokker A.III

- Fokker E.III

- Knoller C.II

- Hansa-Brandenburg B.I

- Hansa-Brandenburg C.I

- Hansa-Brandenburg D.I

- Hansa-Brandenburg G.I(U)

- Aviatik B.III

- Aviatik D.I

- Albatros B.I

- Albatros D.II

- Albatros D.III

- Phönix D.I

Although all of the European powers were unprepared for modern air warfare in the beginning of the conflict, Austria-Hungary was one of the most disadvantaged due to the empire's traditionalist military and civilian leadership combined with a relatively low degree of industrialisation. The Empire's agricultural economy mitigated against innovation. Such industry as it possessed was used to full extent for aircraft manufacture; instead of producing single types of aircraft from dedicated assembly lines, contracts were let to multiple factories, and individual factories were producing multiple types of aircraft. Shortage of unskilled labor also hampered production. Technological backwardness was not limited to the usage of handicraft construction instead of assembly lines. For instance, the most widely used Austro-Hungarian fighter, the Hansa-Brandenburg D.I, lacked the gun synchronization gear that would allow aiming the airplane's nose and firing its weaponry through the propeller.

Wartime production totaled 5,180 airplanes for four years of war; by comparison, Austria-Hungary's major foe, Italy, built about 18,000 in three years.[21] Austro-Hungarian practice included inspection of completed aircraft by army officers before they left the factory.[22]

Before the war, the army also operated four airships at Fischamend:

- Militärluftschiff I (1909-1914), also known as Parseval PL 4.

- Militärluftschiff II (1910-1913), also known as Lebaudy 6 Autrichienne

- Militärluftschiff III (1911-1914)

- Militärluftschiff IV (1912)

Militärluftschiff III was destroyed in a mid-air collision with a Farman HF.20 on 20 June 1914. This ended the airship program. During the war the military expressed interest in purchasing Zeppelins from Germany but failed to acquire any. The navy ordered four to be locally manufactured in 1917 but none were completed before the armistice. They were scrapped by the Allies after the war.

Organization

The K. u. K Luftfahrtruppen was organized into a trilevel organization. At the top was the Fliegerarsenal ("aviation arsenal"), a complex bureaucracy working for a civilian Ministry of War. New airplanes were shipped from factory to a Flars group for acceptance. These groups were located:

- No. I at Aspern, Austria

- No. II at Budapest, Hungary

- No. III at Wiener-Neustadt (later moved to the Anatra plant in Odessa

- No. IV at Campoformido, Italy

- An unnumbered group in Berlin to accept German aircraft[23]

In turn, the Flars forwarded aircraft received to Fliegeretappenpark ("aviation parks"). These Fleps were each responsible for supplying a combat sector of the Austro-Hungarian forces. They supplied hardware and supplies to the aviation units. They also served as repair depots for severely damaged aircraft; they would repair some airplanes that were damaged beyond a frontline unit's repair capabilities, and send the worst back to a factory. There were three Flars at war's beginning; there were eleven by war's end.[24]

Other midlevel units in the K. u. K Luftfahrtruppen were the Fliegerersatzkompanie ("spare flier company"). These replacement depots served a dual purpose. They not only trained and supplied air crew and maintenance staff as replacements to frontline units; they also formed new units to be posted to the front. By war's end, there were 22 of these Fleks.[25]

Finally, there were the line units of the K. u. K Luftfahrtruppen. These Fliegerkompanies were understaffed, seldom having more than eight pilots per unit. There were 77 Fliks in existence by war's end.[26] By 1917, their unit numbers were extended by a letter suffix denoting the unit's mission. For instance:

- 'J' denoted Jagdfliegerkompanie, a fighter squadron

- 'P' meant Photoeinsitzerkompanie, or a single-seater photographic reconnaissance squadron. 'Rb' designated a squadron capable of flying photo sequences and mosaics.

- 'D' meant a squadron was a Divisionsfliegerkompanie flying short range reconnaissance for an army division.

- 'K' showed that the Korpsfligerkompanie was flying short range recon for a corps.

- 'F', by contrast, was a long range recon unit.

- 'S' was attached to ground support squadrons; they were often repurposed 'D' squadrons.

- 'G' denoted a bomber squadron.[27]

Markings

At the outbreak of war, Austro-Hungarian aircraft were brightly painted in red and white bands all along the fuselage. These were swiftly discarded, but the red/white/red bands on the wingtips and tail remained. Aircraft supplied from Germany generally arrived with the familiar black cross marking already applied, and this was adopted officially from 1916, though individual aircraft occasionally kept some red-white-red bands.

Austria-Hungary produced 413 seaplanes during the war.[28] These naval aircraft were more elaborately marked. Typically, a flying boat sported a black cross pattée on a box of white background for national insignia; the boxed crosses were found on top of upper wing surfaces both port and starboard, under both lower wing surfaces, and on the sides of the hull. Additionally, the rudder and elevators were blocked out in red and white; broad red and white bands were sometimes applied to the outboard ends of the wings also. There were also serial numbers on the hull.[29]

Notes

- ↑ O'Connor, p. 258.

- ↑ Franks, et al, p. 107.

- ↑ Franks, et al, p. 107.

- ↑ O'Connor, pp. 238–239, 252, 256.

- ↑ O'Connor, pp. 297–298.

- ↑ Franks, et al, p. 110.

- ↑ Chant, p. 19.

- ↑ Chant, p. 9.

- ↑ O'Connor, p. 258.

- ↑ Chant, p. 10.

- ↑ O'Connor, p. 111.

- ↑ Franks, et al, p. 109.

- ↑ Chant, p. 14.

- ↑ Franks, et al, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Franks, et al, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Chant, p. 15.

- ↑ Franks, et al, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Chant, p. 71.

- ↑ Franks, et al, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Chant, p. 16.

- ↑ Franks, et al, pp.109–110.

- ↑ O'Connor, p. 258.

- ↑ O'Connor, p. 259. Note: Although existent from war's beginning, it was not entitled until March 1915.

- ↑ O'Connor, p. 259.

- ↑ O'Connor, p. 259.

- ↑ O'Connor, pp. 258–259.

- ↑ O'Connor, p. 259. Note: there were several other less common designators.

- ↑ Franks, et al, p. 109.

- ↑ O'Connor, pp. 238–239, 253, 256.

References

- Chant, Christopher (2002). Austro-Hungarian aces of World War 1. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 9781841763767.

- Franks, Norman; Guest, Russell; Alegi, Gregory (1997). Above the war fronts : the British two-seater bomber pilot and observer aces, the British two-seater fighter observer aces, and the Belgian, Italian, Austro-Hungarian and Russian fighter aces 1914-1918. London: Grub Street. ISBN 978-1898697565.

- O'Connor, Martin (January 1986). Air Aces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, 1914-1918 (1st ed.). Oxford: FLYING MACHINES PRESS. ISBN 978-1891268069.

- "How was the first military airplane shot down". National Geographic. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "Ljutovac, Radoje". Amanet Society. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "Radoje Raka Ljutovac – first person in the world to shoot down an airplane with a cannon". Pečat. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- http://www.theaerodrome.com/forum/aircraft-articles/23234-national-markings.html

External links

- The Aerodrome – Austro-Hungarian Aircraft

- Austro-Hungarian World War I aviation

- Aircraft of Austria-Hungary

- Austria-Hungary and the LFT

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Austro-Hungarian Imperial and Royal Aviation Troops. |