Immersion (virtual reality)

Immersion into virtual reality is a perception of being physically present in a non-physical world. The perception is created by surrounding the user of the VR system in images, sound or other stimuli that provide an engrossing total environment.

The name is a metaphoric use of the experience of submersion applied to representation, fiction or simulation. Immersion can also be defined as the state of consciousness where a "visitor" (Maurice Benayoun) or "immersant" (Char Davies)'s awareness of physical self is transformed by being surrounded in an artificial environment; used for describing partial or complete suspension of disbelief, enabling action or reaction to stimulations encountered in a virtual or artistic environment. The degree to which the virtual or artistic environment faithfully reproduces reality determines the degree of suspension of disbelief. The greater the suspension of disbelief, the greater the degree of presence achieved.

Types

According to Ernest W. Adams, author and consultant on game design,[1] immersion can be separated into three main categories:

- Tactical immersion

- Tactical immersion is experienced when performing tactile operations that involve skill. Players feel "in the zone" while perfecting actions that result in success.

- Strategic immersion

- Strategic immersion is more cerebral, and is associated with mental challenge. Chess players experience strategic immersion when choosing a correct solution among a broad array of possibilities.

- Narrative immersion

- Narrative immersion occurs when players become invested in a story, and is similar to what is experienced while reading a book or watching a movie.

Staffan Björk and Jussi Holopainen, in Patterns In Game Design,[2] divide immersion into similar categories, but call them sensory-motoric immersion, cognitive immersion and emotional immersion, respectively. In addition to these, they add a new category:

- Spatial immersion

- Spatial immersion occurs when a player feels the simulated world is perceptually convincing. The player feels that he or she is really "there" and that a simulated world looks and feels "real".

Presence

Presence, a term derived from the shortening of the original "telepresence", is a phenomenon enabling people to interact with and feel connected to the world outside their physical bodies via technology. It is defined as a person's subjective sensation of being there in a scene depicted by a medium, usually virtual in nature (Barfield et al., 1995). Most designers focus on the technology used to create a high-fidelity virtual environment; however, the human factors involved in achieving a state of presence must be taken into account as well. It is the subjective perception, although generated by and/or filtered through human-made technology, that ultimately determines the successful attainment of presence. [4]

Virtual reality glasses can produce a visceral feeling of being in a simulated world, a form of spatial immersion called Presence. According to Oculus VR, the technology requirements to achieve this visceral reaction are low-latency and precise tracking of movements.[5][6][7]

Michael Abrash gave a talk on VR at Steam Dev Days in 2014.[8] According to the VR research team at Valve, all of the following are needed to establish presence.

- A wide field of view (80 degrees or better)

- Adequate resolution (1080p or better)

- Low pixel persistence (3 ms or less)

- A high enough refresh rate (>60 Hz, 95 Hz is enough but less may be adequate)

- Global display where all pixels are illuminated simultaneously (rolling display may work with eye tracking.)

- Optics (at most two lenses per eye with trade-offs, ideal optics not practical using current technology)

- Optical calibration

- Rock-solid tracking – translation with millimeter accuracy or better, orientation with quarter degree accuracy or better, and volume of 1.5 meter or more on a side

- Low latency (20 ms motion to last photon, 25 ms may be good enough)

Immersive virtual reality

Immersive virtual reality is a hypothetical future technology that exists today as virtual reality art projects, for the most part.[9] It consists of immersion in an artificial environment where the user feels just as immersed as they usually feel in consensus reality.

Direct interaction of the nervous system

The most considered method would be to induce the sensations that made up the virtual reality in the nervous system directly. In functionalism/conventional biology we interact with consensus reality through the nervous system. Thus we receive all input from all the senses as nerve impulses. It gives your neurons a feeling of heightened sensation. It would involve the user receiving inputs as artificially stimulated nerve impulses, the system would receive the CNS outputs (natural nerve impulses) and process them allowing the user to interact with the virtual reality. Natural impulses between the body and central nervous system would need to be prevented. This could be done by blocking out natural impulses using nanorobots which attach themselves to the brain wiring, whilst receiving the digital impulses of which describe the virtual world, which could then be sent into the wiring of the brain. A feedback system between the user and the computer which stores the information would also be needed. Considering how much information would be required for such a system, it is likely that it would be based on hypothetical forms of computer technology.

Requirements

- Understanding of the nervous system

A comprehensive understanding of which nerve impulses correspond to which sensations, and which motor impulses correspond to which muscle contractions will be required. This will allow the correct sensations in the user, and actions in the virtual reality to occur. The Blue Brain Project is the current, most promising research with the idea of understanding how the brain works by building very large scale computer models.

- Ability to manipulate CNS

The nervous system would obviously need to be manipulated. Whilst non-invasive devices using radiation have been postulated, invasive cybernetic implants are likely to become available sooner and be more accurate. Manipulation could occur at any stage of the nervous system – the spinal cord is likely to be simplest; as all nerves pass through here, this could be the only site of manipulation. Molecular Nanotechnology is likely to provide the degree of precision required and could allow the implant to be built inside the body rather than be inserted by an operation.

- Computer hardware/software to process inputs/outputs

A very powerful computer would be necessary for processing virtual reality complex enough to be nearly indistinguishable from consensus reality and interacting with central nervous system fast enough.

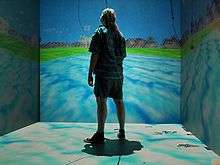

Immersive digital environments

An immersive digital environment is an artificial, interactive, computer-created scene or "world" within which a user can immerse themselves.[10]

Immersive digital environments could be thought of as synonymous with virtual reality, but without the implication that actual "reality" is being simulated. An immersive digital environment could be a model of reality, but it could also be a complete fantasy user interface or abstraction, as long as the user of the environment is immersed within it. The definition of immersion is wide and variable, but here it is assumed to mean simply that the user feels like they are part of the simulated "universe". The success with which an immersive digital environment can actually immerse the user is dependent on many factors such as believable 3D computer graphics, surround sound, interactive user-input and other factors such as simplicity, functionality and potential for enjoyment. New technologies are currently under development which claim to bring realistic environmental effects to the players' environment – effects like wind, seat vibration and ambient lighting.

Perception

To create a sense of full immersion, the 5 senses (sight, sound, touch, smell, taste) must perceive the digital environment to be physically real. Immersive technology can perceptually fool the senses through:

- Panoramic 3D displays (visual)

- Surround sound acoustics (auditory)

- Haptics and force feedback (tactile)

- Smell replication (olfactory)

- Taste replication (gustation)

Interaction

Once the senses reach a sufficient belief that the digital environment is real (it is interaction and involvement which can never be real), the user must then be able to interact with the environment in a natural, intuitive manner. Various immersive technologies such as gestural controls, motion tracking, and computer vision respond to the user's actions and movements. Brain control interfaces (BCI) respond to the user's brainwave activity.

Examples and applications

Training and rehearsal simulations run the gamut from part task procedural training (often buttonology, for example: which button do you push to deploy a refueling boom) through situational simulation (such as crisis response or convoy driver training) to full motion simulations which train pilots or soldiers and law enforcement in scenarios that are too dangerous to train in actual equipment using live ordinance.

Computer games from simple arcade to massively multiplayer online game and training programs such as flight and driving simulators. Entertainment environments such as motion simulators that immerse the riders/players in a virtual digital environment enhanced by motion, visual and aural cues. Reality simulators, such as one of the Virunga Mountains in Rwanda that takes you on a trip through the jungle to meet a tribe of mountain gorillas.[11] Or training versions such as one which simulates taking a ride through human arteries and the heart to witness the buildup of plaque and thus learn about cholesterol and health.[12]

In parallel with scientist, artists like Knowbotic Research, Donna Cox, Rebecca Allen, Robbie Cooper, Maurice Benayoun, Char Davies, and Jeffrey Shaw use the potential of immersive virtual reality to create physiologic or symbolic experiences and situations.

Other examples of immersion technology include physical environment / immersive space with surrounding digital projections and sound such as the CAVE, and the use of virtual reality headsets for viewing movies, with head-tracking and computer control of the image presented, so that the viewer appears to be inside the scene. The next generation is VIRTSIM, which achieves total immersion through motion capture and wireless head mounted displays for teams of up to thirteen immersants enabling natural movement through space and interaction in both the virtual and physical space simultaneously.

Use in medical care

New fields of studies linked to the immersive virtual reality emerges every day. Researchers see a great potential in virtual reality tests serving as complementary interview methods in psychiatric care.[13] Immersive virtual reality have in studies also been used as an educational tool in which the visualization of psychotic states have been used to get increased understanding of patients with similar symptoms.[14] New treatment methods are available for schizophrenia[15] and other newly developed research areas where immersive virtual reality is expected to achieve melioration is in education of surgical procedures,[16] rehabilitation program from injuries and surgeries[17] and reduction of phantom limb pain.[18]

Detrimental effects

Simulation sickness, or simulator sickness, is a condition where a person exhibits symptoms similar to motion sickness caused by playing computer/simulation/video games (Oculus Rift is working to solve simulator sickness).[19]

Motion sickness due to virtual reality is very similar to simulation sickness and motion sickness due to films. In virtual reality, however, the effect is made more acute as all external reference points are blocked from vision, the simulated images are three-dimensional and in some cases stereo sound that may also give a sense of motion. Studies have shown that exposure to rotational motions in a virtual environment can cause significant increases in nausea and other symptoms of motion sickness.[20]

Other behavioural changes such as stress, addiction, isolation and mood changes are also discussed to be side-effects caused by immersive virtual reality.[21]

See also

- Alternate reality game

- Cave automatic virtual environment

- Environmental sculpture

- Escapism

- Immersive design

- Immersive technology

- Interactive art

- Motion sickness

- Narrative transportation

- Neo-conceptual art

- Simulated reality

- Simulation sickness

- Sound art

- Sound installation

- Video installation

- Virtual art

Footnotes

- ↑ Adams, Ernest (July 9, 2004). "Postmodernism and the Three Types of Immersion". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- ↑ Björk, Staffan; Jussi Holopainen (2004). Patterns In Game Design. Charles River Media. p. 206. ISBN 1-58450-354-8.

- ↑ "10.000 moving cities - same but different, interactive net-and-telepresence-based installation 2015". Marc Lee. Retrieved 2017-03-12.

- ↑ Thornson, Carol; Goldiez, Brian (January 2009). "Predicting presence: Constructing the Tendency toward Presence Inventory". International Journal of Human Computer Studies. 67 (1): 62–78. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2008.08.006. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ↑ Seth Rosenblatt (19 March 2014). "Oculus Rift Dev Kit 2 now on sale for $350". CNET. CBS Interactive.

- ↑ "Oculus Rift DK2 hands-on and first-impressions". SlashGear.

- ↑ Announcing the Oculus Rift Development Kit 2 (DK2)

- ↑ Abrash M. (2014). What VR could, should, and almost certainly will be within two years

- ↑ Joseph Nechvatal, Immersive Ideals / Critical Distances. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. 2009, pp. 367-368

- ↑ Joseph Nechvatal, Immersive Ideals / Critical Distances. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. 2009, pp. 48-60

- ↑ pulseworks.com

- ↑ "Thank You".

- ↑ Freeman, D.; Antley, A.; Ehlers, A.; Dunn, G.; Thompson, C.; Vorontsova, N.; Garety, P.; Kuipers, E.; Glucksman, E.; Slater, M. (2014). "The use of immersive virtual reality (VR) to predict the occurrence 6 months later of paranoid thinking and posttraumatic stress symptoms assessed by self-report and interviewer methods: A study of individuals who have been physically assaulted". Psychological Assessment. 26 (3): 841. doi:10.1037/a0036240.

- ↑ http://www.life-slc.org/docs/Bailenson_etal-immersiveVR.pdf

- ↑ Freeman, D. (2007). "Studying and Treating Schizophrenia Using Virtual Reality: A New Paradigm". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 34 (4): 605. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn020.

- ↑ Virtual Reality in Neuro-Psycho-Physiology, p. 36, at Google Books

- ↑ De Los Reyes-Guzman, A.; Dimbwadyo-Terrer, I.; Trincado-Alonso, F.; Aznar, M. A.; Alcubilla, C.; Pérez-Nombela, S.; Del Ama-Espinosa, A.; Polonio-López, B. A.; Gil-Agudo, Á. (2014). "A Data-Globe and Immersive Virtual Reality Environment for Upper Limb Rehabilitation after Spinal Cord Injury". XIII Mediterranean Conference on Medical and Biological Engineering and Computing 2013. IFMBE Proceedings. 41. p. 1759. ISBN 978-3-319-00845-5. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-00846-2_434.

- ↑ Llobera, J.; González-Franco, M.; Perez-Marcos, D.; Valls-Solé, J.; Slater, M.; Sanchez-Vives, M. V. (2012). "Virtual reality for assessment of patients suffering chronic pain: A case study". Experimental Brain Research. 225: 105. doi:10.1007/s00221-012-3352-9.

- ↑ "Oculus Rift is working to solve simulator sickness". Polygon. Retrieved 2015-05-05.

- ↑ So, R.H.Y. and Lo, W.T. (1999) "Cybersickness: An Experimental Study to Isolate the Effects of Rotational Scene Oscillations." Proceedings of IEEE Virtual Reality '99 Conference, March 13–17, 1999, Houston, Texas. Published by IEEE Computer Society, pp. 237–241

- ↑ http://www.agocg.ac.uk/reports/virtual/37/37.pdf

References

- media.ford.com

- on.aol.com

- Reyes, Stephanie. "Ford brings virtual reality presentation to UCF.", September 2012.

- Christiane Paul, Digital Art, Thames & Hudson Ltd.

- Oliver Grau, "Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion" MIT-Press, Cambridge 2003

- Timothy Murray, Derrick de Kerckhove, Oliver Grau, Kristine Stiles, Jean-Baptiste Barrière, Dominique Moulon, Maurice Benayoun Open Art, Nouvelles éditions Scala, 2011, French version, ISBN 978-2-35988-046-5

- Allen Varney, (August 8, 2006). "Immersion Unexplained" in "The Escapist"

- Frank Popper, "From Technological to Virtual Art", MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-16230-X.

- Oliver Grau (Ed.), Media Art Histories, MIT-Press, Cambridge 2007

- Joseph Nechvatal, "Immersive Excess in the Apse of Lascaux", Technonoetic Arts 3, no3. 2005

- Adams, Ernest (July 9, 2004). "Postmodernism and the Three Types of Immersion". Gamasutra. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- Björk, Staffan; Jussi Holopainen (2004). Patterns In Game Design. Charles River Media. p. 423. ISBN 1-58450-354-8.

- Edward A. Shanken, Art and Electronic Media. London: Phaidon, 2009. ISBN 978-0-7148-4782-5

- Joseph Nechvatal Towards an Immersive Intelligence: Essays on the Work of Art in the Age of Computer Technology and Virtual Reality (1993–2006). Edgewise Press. New York, N.Y. 2009

- Joseph Nechvatal, Immersive Ideals / Critical Distances. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. 2009

External links

- Annual Summit on Immersive Technology

- pdf download of Joseph Nechvatal's text book: Immersive Ideals / Critical Distances. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing. 2009

- Audio and Game Immersion PhD thesis about game audio (the IEZA Framework) and immersion.

- "Improvising Synesthesia: Comprovisation of Generative Graphics and Music" by Joshua B. Mailman, in Leonardo Electronic Almanac v.19 no.3, Live Visuals, 2013, pp. 352–84, about two immersive systems for improvising music and graphics through dance-like motion detected by an infrared video camera and other sensors.