Imamate of Futa Toro

| Imamate of Futa Toro | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

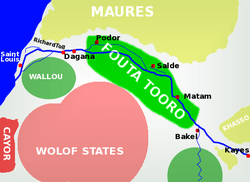

Futa Toro and neighbors, circa 1850 | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Orefonde | |||||||||||

| Languages | Pulaar language | |||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | |||||||||||

| Government | Theocratic Monarchy | |||||||||||

| Almaami | ||||||||||||

| • | 1776–1804 | Abdul Kaader | ||||||||||

| • | 1875–1891 | Abdul Ba Bakar | ||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||

| • | Established | 1776 | ||||||||||

| • | Torobe Islamic Revolution | |||||||||||

| • | Fractured state absorbed into Tukulor Empire | |||||||||||

| • | Incorporated into Senegal Colony | 1877 | ||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 1861 | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

The Imamate of Futa Toro (1776-1861) was a pre-colonial West African theocratic state of the Fula-speaking people (Fulɓe and Toucouleurs) centered on the middle valley of the Senegal River. The region is known as Futa Toro.[1]

Origins

Futa Toro is a strip of agricultural land along both sides of the Senegal River.[2][lower-alpha 1] The people of the region speak Pulaar, a dialect of the greater Fula languages spanning West Africa from Senegal to Cameroon. They identify themselves by the language, which gives rise to the name Haalpulaar'en (those who speak Pulaar). The Haalpulaar'en are also known as Toucouleur people, a name derived from the ancient state of Takrur. From 1495 to 1776, the country was part of the Denanke Kingdom. The Denianke leaders were a clan of non-Muslim Fulbe who ruled over most of Senegal.[1]

A class of Muslim scholars called the Torodbe[lower-alpha 2] seem to have originated in Futa Toro, later spreading throughout the Fulbe territories. Two of the Torodbe clans in Futa Toro claimed to be descended from a seventh-century relative of one of the companions of the prophet Muhammad who was among a group of invaders of Futa Toro. The Torodbe may well have already been a distinct group when the Denianke conquered Futa Toro.[3]

In the last quarter of the seventeenth century the Mauritanian Zawāyā reformer Nasir al-Din launched a jihad to restore purity of religious observance in the Futa Toro. He gained support from the Torodbe clerical clan against the warriors, but by 1677 the movement had been defeated.[4] After this defeat, some of the Torodbe migrated south to Bundu and some continued on to the Futa Jallon.[5] The farmers of Futa Toro continued to suffer from attacks by nomads from Mauritania.[2] By the eighteenth century there was growing resentment among the largely Muslim lower class at lack of protection against these attacks.[1]

Jihad

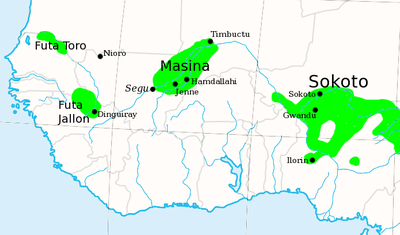

In 1726 or 1727 Karamokho Alfa led a jihad in Futa Jallon to the south, leading to formation of the Imamate of Futa Jallon. This was followed by a jihad in Futa Toro between 1769 and 1776 led by Sulaymān Baal.[6] In 1776 the Torodbe threw out the ruling Denianke Dynasty.[2] Sulayman died in 1776 and was succeeded by Abdul Kader ('Abd al-Qadir), a learned teacher and judge who had studied in Cayor.[7]

Abdul Kader became the first almami[lower-alpha 3] of the theocratic Imamate of Futa Toro.[2] He encouraged construction of mosques, and pursued an aggressive policy towards his neighbors.[7] The Torodbe prohibited the trade in slaves on the river. In 1785 they obtained an agreement from the French to stop trading in Muslim slaves and to pay customs duties to the state. Abdul Kader defeated the emirates of Trarza and Brakna to the north, but was defeated and captured when he attacked the Wolof states of Cayor and Waalo around 1797. After his release the jihad impetus had been lost. By the time of Abdul Kader's death in 1806 the state was dominated by a few elite Torodbe families.[2]

Government

The Imamate was ruled by an Almami elected from a group of eligible lineages who possessed the necessary credentials of learning by local chiefs called jaggorde or jaggorgal. There was an electoral council, which contained a fixed core and a fluctuating periphery of members. Two families were eligible for the post of Almami, the Lih of Jaaba in Hebbiyaabe province and the Wan of Mbummba in Laaw province.[1] Almamis continued to be appointed in Futa Toro throughout the nineteenth century, but the position had become ceremonial.[7]

The Almamate survived through the nineteenth century albeit in a much weaker state. The state was governed officially by the Almami, but effective control lay with regional chiefs of the central provinces who possessed considerable land, followers and slaves. The struggle of various coalitions of electors and eligibles further hastened the decline of the Imamate.[1] In the middle of the nineteenth century Toro was threatened by the French under the leadership of Governor Louis Faidherbe.[9] The Imamate at this time was divided into three parts. The Central region contained the seat of the elected Almani, subject to a council of 18 electors. The west, called the Toro region, was administered by the Lam-Toro. The east, called the Futa Damga was theoretically administered by a chief called El-Feki, but in practice he had only nominal authority.[10]

Collapse

El Hadj Umar Tall, a native of Toro, launched a jihad in 1852. His forces succeeded in establishing several states in the Sudan to the east of Futa Toro, but the French under Major Louis Faidherbe prevented him from including Futa Toro into his empire.[2] To achieve his goals, Umar recruited heavily in Senegambia, especially in his native land. The recruitment process reached its culmination in a massive drive in 1858 and 1859. It had the effect of undermining the power of the Almaami even more.[1] The authority of the regional chiefs, and particularly that of the electors, was compromised much less than that of the Almaami. Some of these leaders became fully independent and fought off the French and Umar Tall on their own. As a result, the Almaami and the chiefs began to rely increasingly on French support.[1] 'Umar was defeated by the French at Medine in 1857, losing access to Futa Toro.[11]

Futa Toro was annexed by France in 1859, although in practice it had long been within the French sphere of influence.[9] In 1860 Umar concluded a treaty with the French in which he recognized their supremacy in Futa Toro, while he was recognized in Kaarta and Ségou.[11] In the 1860s the almami of Futa Toro was Abdul Boubakar,[lower-alpha 4] but his power was nominal.[9] In June 1864 the Moors and the Booseya group of Fula collaborated in plundering trade barges that had become stranded near Saldé in the east, drawing savage French reprisals against both groups.[9]

The French generally encouraged strongmen such as Abdul Bokar Kan of Bossea, Ibra Wan of Law and Samba Umahani in Toro when they attacked caravans in the region, since they hoped that would discourage migration away from the region to Umar's new state.[13] Fear of continuing Muslim migration, however, led the military authorities to attack France's remaining clients in 1890. Abdul Bokar Kan fled but was murdered in August 1891 by the Berbers of Mauritania.[14] The French consolidated their complete control of the region.[1]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ The word Futa was a general name the Fulbe gave to any area they lived in, while Toro was the actual identity of the region for its inhabitants.

- ↑ The name "Torodbe" comes from the verb tooraade, meaning to beg for alms in reference to the Qur'anic school pupils who supported themselves in that way. The label of begging was likely applied by the Denanke court who made fun of the Muslim underclass.[1]

- ↑ Almami is derived from the Arabic al-Imam, meaning the one who leads in prayer.[8]

- ↑ There is some confusion between Abdul Bubakar of the Imamate of Futa Jallon and Abdul Bubaker of Futa Toro. According to Charles Augustus Ludwig Reichardt, in the introduction to his 1879 Fula language grammar, the entire country between the upper Niger River and the Senegal River was occupied by Fula people. He placed the seat of government at Timbo [in Futa Jallon], saying that Futa Jallon had spread towards the Senegal River until it met the Sisibo Fula [in Futa Toro]. They had set up a joint system of government, with two Imams named Omar and Ibrahim, also called kings. Timbo was still the capital.[12] Another source says the two almamis in 1876 were absolutely unknown to each other. They were Ibrahim-Sawri in Futa Djallon and Abd-ul-Bubakar in the Senegal Futa [Futa Toro]. The title almami was a corruption of "el-Imam". The Futa did not have a word for "king": the governors were subordinate to the almami.[12]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Overview of Fuuta Tooro - Jamtan.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Klein 2005, p. 541-542.

- ↑ Gomez 2002, p. 36.

- ↑ Gray 1975, p. 205.

- ↑ Gray 1975, p. 206.

- ↑ Stanton, Ramsamy & Seybolt 2012, p. 148.

- 1 2 3 Lapidus 2002, p. 419.

- ↑ Hughes & Perfect 2008, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 McDougall & Scheele 2012, p. 151.

- ↑ Grimal de Guiraudon 1887, p. 19.

- 1 2 Lapidus 2002, p. 425.

- 1 2 Grimal de Guiraudon 1887, p. 19-20.

- ↑ Hanson 1996, p. 75.

- ↑ Fage, J, D. & al. The Cambridge History of Africa, vol. 6, p. 261. Cambridge University Press (Cambridge), 1995 reprinted 2004. Accessed 18 Apr 2014.

Sources

- Gomez, Michael A. (2002-07-04). Pragmatism in the Age of Jihad: The Precolonial State of Bundu. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52847-4. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- Gray, Richard (1975-09-18). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20413-2. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- Grimal de Guiraudon, Th. (1887). Notes de linguistique africaine: les Puls. E. Leroux. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- Hanson, John H. (1996). Migration, Jihad, and Muslim Authority in West Africa: The Futanke Colonies in Karta. Indiana University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-253-33088-8. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- Hughes, Arnold; Perfect, David (2008-09-11). Historical Dictionary of The Gambia. Scarecrow Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8108-6260-9. Retrieved 2013-02-17.

- Klein, Martin A. (2005). "Futa-Tooro: Early Nineteenth Century". Encyclopedia of African History. 1. Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 541. ISBN 978-1-57958-245-6. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2002-08-22). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- McDougall, James; Scheele, Judith (2012-06-08). Saharan Frontiers: Space and Mobility in Northwest Africa. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-00131-3. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- "Overview of Fuuta Tooro". Jamtan. Retrieved 2013-02-17.

- Stanton, Andrea L.; Ramsamy, Edward; Seybolt, Peter J.; Carolyn M. Elliott (2012-01-05). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-8176-7. Retrieved 2013-02-10.