Il Perdono di Gesualdo

| Il Perdono di Gesualdo | |

|---|---|

Il Perdono di Gesualdo, Santa Maria delle Grazie Church | |

| Artist | Giovanni Balducci |

| Year | 1609 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Movement | Religious Painting |

| Dimensions | 481 cm × 310 cm (189 in × 120 in) |

| Location | Santa Maria delle Grazie Church, Italy |

Il Perdono di Gesualdo (in English, The Pardon of Gesualdo) is an altarpiece created in 1609 by the Florentine painter Giovanni Balducci for a commission from the madrigal composer Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa, of the kingdom of Naples. Conserved in the private chapel of Gesualdo’s church, Santa Maria delle Grazie, the painting underwent important restorations in the late twentieth century, following the destructive Irpinia earthquake of 1980.

A unique testimony, in the field of religious painting, to the devotion of the composer prince, Il Perdono di Gesualdo has been the object of numerous commentaries and analyses since the seventeenth century. These interpretations, focusing on the musician’s murder of his adulterous wife and her lover, have shrouded the artwork in mystery.

In the early twenty-first century, art historians and musicologists agree that certain ambiguities in the Perdono reflect the fascinating personality of its patron. The American musicologist Glenn Watkins believes the painting to be the only authentic portrait of Gesualdo.

Introduction

Location

Il Perdono di Gesualdo was commissioned for the high altar in Carlo Gesualdo’s private chapel, in the church attached to the Capuchin convent founded in the mid-1580s by his father Fabrizio.[1]

This convent, today largely destroyed, “once formed a beautiful monastic complex with a large garden, vast convent buildings, and a magnificent church: Santa Maria delle Grazie."[2] Denis Morrier points out that this monastery was “endowed with a comfortable annuity by Gesualdo.” The chapel bears an inscription recalling that the prince began its construction in 1592:[3]

Dominvs Carolvs Gesvaldvs |

Don Carlo Gesualdo, |

In fact, the composer-prince oversaw the construction of “two convents, one Dominican, the other Capuchin, and their respective churches: Santissimo Rosario, completed in 1592, and Santa Maria delle Grazie, which Gesualdo never saw completed.”[4]

According to Catherine Deutsch, “certain historians[5] have been tempted to draw a connection between the founding of these institutions and the murder that Gesualdo had just committed” against his wife, Maria d’Avalos, caught red-handed in adultery with Fabrizio Carafa, Duke of Andria, at Gesualdo’s palace in Naples, during the night of October 16 or 17, 1590.[6] This interpretation of “a tentative remission of his recent sins” applies equally to the Perdono, a painting loaded with allegorical figures that invite multiple levels of interpretation.[7]

Description

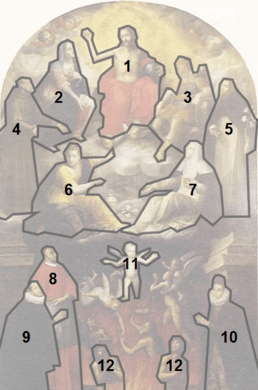

The painting presents itself as a Last Judgement scene with ten main characters, including Gesualdo and his second wife. The prince is supplicating Christ by the side of his maternal uncle, St. Charles Borromeo, who is clothed in cardinal red and positioned as his protector.[8]

Denis Morrier points out the canvas’ three-tiered composition:

- “At the summit, Christ Pantocrator, in majesty, judges the living and the dead. He is surrounded by several saints, among whom we recognize the Virgin Mary, ‘consoler of the afflicted,’ who intercedes with her son for the pardon of sinners, and Mary Magdalene, symbol of repentance,[9]”

- In the middle section, we see the composer supported by his uncle St. Charles Borromeo. Across from him is his wife, Eleonora d’Este, clothed “in the Spanish style,”[10]

- “In the lower section we see purgatory, where a man and a woman wait, lost in the flames.”[11]

Moreover, Glenn Watkins, who identifies the two upper levels of the canvas as “a typical sacra conversazione,”[12] points out the guardian figures of the archangel Michael—sitting near Christ and somewhat effaced—and of St. Francis of Assisi and St. Dominic, the founders of the religious orders that occupied the two convents built by Gesualdo.[13]

History

According to Glenn Watkins, the imposing dimensions of the Perdono di Gesualdo testify to the patron's preoccupation not only with grandeur, but also with religious fervour.[14]

Commission

The attribution of the painting to a painter remained hypothetical for a long time. According to Denis Morrier, “Silvestro Bruno, and Girolamo Imparato, two minor mannerist painters” of the Neapolitan school, were among the first artists considered.[15] Following the painting’s restoration, more advanced research has enabled the attribution of the Perdono di Gesualdo to Giovanni Balducci and to his Florentine workshop.[16] Protégé of the Cardinal Gesualdo in Rome, the artist followed his master to Naples, where the cardinal presided as dean of the College of Cardinals, and then as Archbishop in 1596. The historian Francesco Abbate considers Giovanni Balducci to have been the “official painter of Gesualdo’s house” from this date on.[17]

The exact date of the commission is unknown, but the painting, which follows precise instructions in terms of character representation and composition, was completed in 1609.[18] Today, the revelatory circumstances surrounding this commission are well established: Glenn Watkins sees in them a perfect example of Ars moriendi, “where elements of the Last Judgement and the search for pardon are principle themes.”[19]

In fact, the American musicologist paints a powerful picture of the state Gesualdo found himself in during the early seventeenth century: “the Prince’s health was in such decline that many feared for his life. It was also the year of witchcraft trials, a period in which the psychological strain would have been extraordinary. A review of his life could bring little consolation: a first marriage had ended in infidelity and murder; a second marriage had provided only a momentary consolation before deteriorating into an untenable domestic situation; the son from his first marriage was estranged and living elsewhere; and a son born of his second marriage had died in October 1600.”[20]

Deterioration

The painting was significantly damaged during the earthquake of November 23, 1980. The earthquake’s epicentre was located in Conza della Campania, a feudal domain of the Gesualdos in the province of Avellino since the fifteenth century.[21]

This event was catastrophic for the two convents built on the prince’s orders,[22] for his castle in Gesualdo (which was never restored) and for the town, which counted 2,570 dead and 9,000 injured and homeless.[23] A large part of the Gesualdos’s family heritage in Venosa was thus irremediably lost, the family line having been extinguished with the death of the composer on September 8, 1613.[24] Glenn Watkins concludes from this that “history is a story of loss and recovery and comes down to us in bits and pieces.”[25]

Restoration

The painting had suffered other damages before the 1980 earthquake. During his first visit to Santa Maria delle Grazie, in 1961, Glenn Watkins noticed “that the altarpiece had been transferred to the wall at the left of the main altar but also that it had a prominent tear at the lower left-hand side.”[26] It was reproduced with this tear on the cover of the first edition of Watkins’s book Gesualdo, The Man and his Music in 1973.[27]

After the earthquake, which destroyed a large portion of the church, the painting remained stored on its side on the ground for many years. Restorative work was decided on at the end of the 1990s, and the canvas was remounted in its original location on June 6, 2004.[28]

This work led to a number of discoveries concerning the state of the original painting. The restoration uncovered several pentimenti, such as Mary Magdalene’s originally more open décolleté. But the influence of the Counter-Reformation affected more than the painting's modesty: the most impressive alteration was done to the figure of Eleonora d’Este, entirely covered by a Capuchin Poor Clare nun in a monastic robe.[29]

The identification of the princess of Venosa put an end to a controversy that had agitated the community of historians and musicologist up to that point. Among interpretations suggested for this figure in the Perdono, Glenn Watkins mentions Sister Corona, the sister of Cardinal Borromeo,[30] as well as the wife of the duke Gesualdo assinated.[31] The restored figure's court dress and collarless ruff are in keeping with the grandee attire worn by the Duke of Andria.[32]

Technical considerations

Giovanni Balducci's work on the Perdono di Gesualdo has not been the object of any particular commentary. Judgements of the Florentine painter’s technique in general tend to be critical. According to Françoise Viatte, “his drawing style, directly descendent from the teaching of Vasari and very close to that of Naldini, is marked by an attachment to traditional models of representation.”[33] William Griswold, curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, adds that, “Although he was a prolific artist, profoundly influenced by Naldini, Balducci was a timid draftsman, and his pen drawings—characterized by thin, nervous contours and pale washes—are seldom to be confused with those of his master.”[34]

Francesco Abbate therefore describes the Perdono di Gesualdo as “a prestigious commission” for a painter of minor importance who had not found a way to impose himself in the face of “fierce competition in Rome,”[35] and whose pictorial technique was readily critiqued by his colleague Filippo Baldinucci as “mannered and somewhat crude.”[36] From the seventeenth century to the present, art historians and music critics have been interested in the painting primarily for the “history” it evokes.[37]

Analysis

The characters represented in the Perdono di Gesualdo can be classified into three categories: members of Carlo Gesualdo’s family treated in a realist manner, sacred figures treated in a classical manner, and allegorical figures, more challenging to interpret.

Portraits

The first group is limited to the Princess and Prince of Venosa and the latter’s uncle. The restored figure of Eleonora d’Este, however, shows her strangely isolated from the rest of the figures.[38]

Eleonora d’Este

Gesualdo’s wife is the only figure whose gaze is turned toward the viewer. In a way, the modified version of this figure, with her gaze turned toward Christ, was in greater harmony with the attitudes of the other figures.[39] In his analysis of the Perdono, Glenn Watkins suggests that Gesualdo intended for his wife to appear “as the sole person in the painting to maintain a blank frontal stare, a completely passive witness to the implorations of forgiveness.”[40]

Biographical information on the couples marriage sheds some light on the nature of their conjugal relations: with the support of her brother Cesare d’Este, Eleonora obtained her husband’s permission to return to the court of Modena, where she stayed first from October 1607 to November 1608, then again from October 1609 to November 1610, “not without provoking the irritation of Gesualdo, who implored her to return to the conjugal residence.”[41]

Considering this absence, her portrait was likely created from a pre-existing portrait, such as the one conserved in the house of Este museum at the Ducal Palace of Modena, rather than from life.[42]

Carlo Gesualdo

The portrait of Carlo Gesualdo has an otherworldly eloquence: clothed in black, his tense face resting on his Spanish ruff, his gaze dark despite his blue-grey eyes, his hair cut short, his beard sparse, his air austere and his hands joined together. Glenn Watkins describes him as “a sallow-faced El Greco-like figure.”[43]

In the first monograph on the composer-prince, Gesualdo: Musician and Murderer (1926), Cecil Gray claims that “the portrait of the Prince contained in this picture makes a curiously disagreeable impression on one.”[44] Analyzing the traits of Gesualdo’s face, Gray discovers “a character of the utmost perversity, cruelty, vindictiveness. At the same time it is a weak rather than a strong face—almost feminine, in fact. Physically he is the very type of the degenerate descendant of a long aristocratic line.”[45]

This image of the composer has descended fixedly through history, even more so than that of his wife. For this reason, the Perdono di Gesualdo is of major interest to music historians. In an article on the portraits of Gesualdo (“A Gesualdo Portrait Gallery”), Glenn Watkins points out that, outside of the Perdono of 1609, only three painted portraits of the composer exist. The first, uncovered in 1875 and created in the late eighteenth century, is so remote from the other representations of the Prince of Venosa that the musicologist gives it no credit. Gesualdo appears in it as “a bloated, obese figure with Daliesque moustache and billy-goatee.”[46]

The second, dating probably from the seventeenth century but only discovered in the early 1990s, has been reproduced on the cover of numerous scores. Gesualdo’s names and titles are inscribed in large print, but the canvas has not been the object of any analysis, and its authenticity therefore remains undetermined.[47]

A final portrait, a fresco in Gesualdo’s Church of san Nicola, shows the composer––sword at his side, hands together, smiling enigmatically––following the Pope Liberius among a procession of cardinals with his wife Eleonora, all under the benevolent gaze of the Virgin and the baby Jesus.[48] Although formally dated to the first half of the seventeenth century, this work was certainly begun after Gesualdo’s death.[49]

According to some historians, the figures represented in this latter portrait are actually the princess Isabella Gesualdo di Venosa, the composer’s granddaughter, and her husband, Don Niccolo Ludovisi.[50] Glenn Watkins concludes from this “that the Santa Maria delle Grazie altarpiece offers us the only authenticated portrait of our composer.”[51]

Charles Borromeo

The portrait of St. Charles Borromeo in the Perdono is interesting in several ways. The noble figure of the cardinal draws our attention: he holds himself upright, and his scarlet robe and immaculately white surplice highlight his nephew’s dark silhouette.[52] The bishop of Milan, deceased November 3, 1584, was the object of great devotion in Italy, but more importantly he was Gesualdo’s godfather,[53] and his godson held him in “almost obsessive veneration.”[54]

The cardinal’s position in the painting ensures a transition between the terrestrial sphere, where Eleonora d’Este and Carlo Gesualdo kneel, and the celestial sphere, where the saints intercede with Christ for the salvation of Gesualdo’s soul. However, Charles Borromeo’s canonization by the Pope Paul V only occurred in 1610, that is, one year after the completion of the painting, “securing an even more powerful resonance for Gesualdo’s altar commission.”[55]

Devotion or exorcism

In his analysis of the Perdono di Gesualdo, Glenn Watkins presents the seven celestial figures as elements of a conventional sacra conversazione,[56] only to then show the ambiguity that distinguishes them. This ambiguity sets off the outline of the composition and underlines the importance Gesualdo attached to certain devotional practices[57] and spiritual exercises, such as flagellation,[58] which contributed to his posthumous celebrity.[59]

Saints at the Devil's Prey

Pointing to the influence of Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend on Renaissance art, Glenn Watkins reveals a layer of signification that a modern spectator might not see: “The collection of saints in the altarpiece clearly held a special meaning as all of them, like Gesualdo, had encountered the devil or demons but had nonetheless prevailed.”[60]

In his first book, Gesualdo, the Man and his Music, the American musicologist notes that the prince thought of the flagellation that adolescent boys, hired for this purpose, performed on him as a form of exorcism to drive his demons away.[61] Watkins also reminds us that “St. Francis exorcising the demons from Arezzo became a popular subject for artists”[62] since the thirteenth century.

Catherine of Siena

Considering that Catherine of Siena was the object of great veneration both at the Vatican and all over Italy, Gesualdo must have been particularly impressed by her fight against the devil,[63] which he could read about in her major work, The Dialogue.

Deceased in 1380, Catherine of Siena had supported Pope Urban VI during the Western Schism.[64] In recognition, Pope Pius II canonized her in 1461.[65] Glenn Watkins observes that Urban VI was Neapolitan, and that the succession of Pius II elevated Gesualdo’s maternal great-uncle to the throne of St. Peter under the name of Pius IV in 1559. The presence of St. Catherine of Siena therefore appears “as a prefiguration of Borromeo’s own ascension to saintly status the very next year.”[66]

Mary Magdalene

The presence of Mary Magdalene has long puzzled historians.[67] Three possible Maries have been proposed for this figure: the “sinful woman” mentioned in the Gospel of Luke (Lk 7:37-50), the sister of Martha and Lazarus (Lk 10:38-42) and Mary of Magdala, who is the most probable reference.[68]

Glenn Watkins describes the basis of the consensus between historians and musicologist on the identification of Mary Magdalene. In the New Testament, she is the first witness of the resurrection: “When Jesus rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, out of whom he had driven seven demons” (Mk 16:9).[69]

Mary Magdalene is the only character whose face is turned toward Gesualdo rather than toward Christ. In the sphere of the saints, she offers a pendant to the protective figure of St. Charles Borromeo. The characteristically Baroque rhetoric[70] of glances and gestures in the painting places Gesualdo and Christ the saviour on a continuous axis.[71] Moreover, Cecil Gray observes that the Virgin Mary and the archangel Michael, pointing toward Gesualdo from each side of Christ, form an arrow that complements this diagonal line.[72]

According to Glenn Watkins, in his 2010 book The Gesualdo Hex, “Gesualdo would have viewed Mary Magdalene primarily as a sinner who, according to the Gospel, found salvation through the power of exorcism, and is it in this context that she is portrayed in the altarpiece as his most personal intercessor in Gesualdo’s search for eternal pardon.”[73]

Allegories or "Black Legends"

Three unidentified figures in the Perdono di Gesualdo have attracted particular attention: the man, the woman, and the winged child in purgatory. Denis Morrier believes that “they can be approached as purely symbolic representations.” However, historians and musicologists have proposed diverse interpretations by lending a complacent ear to the dark tales of the composer’s biography.[74]

Adultery and double murder

According to Denis Morrier, “traditionally, the figures of the man and the woman have been interpreted as the tormented souls of Maria d’Avalos and the Duke of Andria,”[75] assassinated in 1590.

A great deal of ink has been spilled over this event, as much in Neapolitan and Roman chronicles of the sixteenth century[76] as in sonnets, quatrains and other occasional poems; Tasso composed three sonnets and one madrigal about this double homicide and “was soon followed by a number of poets. The theme thus became a topos among others, providing beaux-esprits with ample subject matter to poeticise.”[77] In France, Pierre de Bourdeille, Lord of Brantôme, took up the narrative in his Lives of Noble Women (first discourse: “On the ladies who make love and cuckold their husband”).[78][79]

According to Catherine Deutsch, “even if the viceroy sought to suppress the affaire, either of his own accord or through the Gesualdos’s insistence, this double crime left a profound and durable mark on the consciousness of Naples, Italy, and the rest of Europe.”[80] Denis Morrier sees the “Gesualdo affaire” as the crime of the century,[81] a crime that definitively established the composer’s reputation through “the extraordinary publicity” that accompanied it.[82]

Though not pursued by justice, “he paid in a certain measure for his acts, as he was ostracized from Neapolitan aristocracy” and “this forced retirement affected other members of Gesualdo’s family, notably his father, Fabrizio, who died December 2, 1591, far from Naples, in his castle in Calitri.”[83] Consequently, at the end of a year of exile, Carlo Gesualdo became the head of his family at twenty-five years of age, and one of the richest landowners in all of Southern Italy.[84]

In the popular imagination, a black legend soon surrounded the composer. “Crime and divine punishment, fault and expiation: barely twenty years after the death of the prince, all the ingredients were already in place for the mythic edification of the character of Gesualdo,” who become “the bloody murderer of the nineteenth century historiographies, the monster tortured by his conscience and by the ghost of his wife.”[85]

Infanticide

Dennis Morrier notes that “the presence of the small child at the centre of the painting has caused much speculation.”[86] Three possible explanations have been considered.

According to “a legend propagated in the village of Gesualdo, the representation of this child in purgatory would be the proof of a second assassination attributable to Carlo. In fact, this popular legend evokes the birth, after that of Don Emmanuele around 1587, of a second child to Donna Maria."[87] During his reclusion, “Believing that he recognised in its features a resemblance to the Duke of Andria, he had the cradle, and within it the unfortunate child, suspended by means of silk ropes attached to the four corners of the ceiling in the large hall of his castle. He then commanded the cradle to be subjected to ‘violent undulatory movements,’ until the infant, unable to draw breath, ‘rendered up its innocent soul to God’.”[88] It is even said that Gesualdo covered up the child’s cries with the sound of musicians performing one of his macabre madrigals.

The docufiction Death for Five Voices, directed by Werner Herzog for ZDF in 1995, associates this event with the madrigal Belta, poi che t’assenti of the Sixth Book of Madrigals,[89] a composition “on the beauty of death”[90] with audacious chromatics that “completely disorient the listener”[91] even today:

Beltà, poi che t'assenti |

Beautiful, you will recognize |

However, for twentieth century historians, “it is clear that this horrible crime, many times retold and embellished, is nothing but an invention of the ancient chroniclers. No official document has ever confirmed it.”[92]

Another story recounts that “Maria d’Avalaos was supposedly pregnant by the Duke of Andria when her husband killed her. The child in the painting would be this little lost soul in limbo before being born. Here again, no testimony worthy of faith can be cited to confirm this thesis.”[93]

There is “another explanation, less sensational but more plausible,”[94] for the presence of this infant soul. Gesualdo’s second son, born on January 20, 1595, from his marriage to Eleonora d’Este, named Alfonsino in homage to the Duke of Ferrare, Alfonso d’Este,[95] died on October 22, 1600, “dealing a fatal blow to the conjugal relations of the princely couple.”[96] According to Glenn Watkins, “we see a child understandably identified by many as Alfonsino, […] now somewhat unusually provided with wings and rising from the flames of purgatory.”[97]

The hostility shown by Eleonora’s family, especially by her brother Cesare d’Este, towards the Prince of Venosa comes across in their private correspondences, where “Carlo Gesualdo figures as a veritable monster who even prevented his wife from assisting her young son in his agony.”[98] They accuse him, directly and indirectly, of the death of his own child. For this reason, “commentators of the Perdono di Gesualdo could not help themselves from associating these allegorical figures with the assassinated lovers and with an even more horrible crime: infanticide.”[99]

Mutual pardon

Denis Morrier mentions yet another interpretive tradition. In August every year, the town of Gesualdo re-enacts an event that marked the city: the mutual pardon of Prince Carlo and his son Emmanuele. In the narratives of the early seventeenth century chroniclers, this ceremony is tied to the reconciliation, as well as to the very close deaths, of the two princes in 1613. Don Ferrante della Mara, chronicler of the great Neapolitan families,[100] evokes this ultimate drama of Gesualdo's life in his Rovine di case Napoletane del suo tempo (1632):

“It is in this state that Gesualdo died miserably, not without having known, for his fourth misfortune, the death of his only son, Don Emmanuele,[101] who hated his father and ardently desired his death. The worst was that this son disappeared without having left a child for the survival [of their house], as he had only two daughters by Donna Maria Polissena of Furstenberg, Princess of Bohemia.”[102]

This Mutual Pardon of Gesualdo is exactly contemporary to the completion of the Perdono di Gesualdo. In fact, Eleonora d’Este described the reunion of the father and his son in a letter date March 2, 1609, addressed to her brother Cesare: “My son Lord Don Emmanuele is here at our place (in Gesualdo), and he is seen with great joy and pleasure by his father, since the differences that opposed them are calmed, for the greatest pleasure of all, and in particular for myself who loves him so.”[103]

Painting and music

Glenn Watkins, who worked on the recovery of Gesualdo’s motets, draws a parallel between the composer’s religious music and the painting the prince commissioned.[104]

Resonances in Gesualdo’s oeuvre

Among the collections of religious music published in Naples in 1603, the book of Sacrae Cantiones for six voices contains a single motet for seven voices, Illumina nos, conclusion and culmination of the work, “composed with a singular artifice” (singualari artificio compositae):[105]

Illumina nos, misericordiarum Deus, |

Enlighten us, God of mercy, |

For the American musicologist, this piece sheds a new light on the Mary Magdalene who appears in the Perdono: “The seven devils of Mary Magdalene? Sevenfold Grace? Seven-voice counter-point?”[106] In a letter dated June 3, 1957, addressed to Robert Craft with a view of recording the three motets recomposed by Stravinsky under the title Tres Sacrae Cantiones (Da Pacem Domine, Assumpta est Maria and Illumina nos), the composer Ernst Krenek emphasizes how “In the tradition of the Church, the Holy Ghost has always been associated with the figure ‘seven’ […] The source of it seems to be Isaiah XI, 2, where the ‘seven gifts’ are attributed to the Spirit of the Lord.”[107]

Moreover, Glenn Watkins suggests that the motet Assumpat est Maria can be read as a musical equivalent to the representation of the Virgin who, surrounded by cherubs, sits to the right of Christ in the Perdono di Gesualdo.[108]

The subtleties of harmony and counterpoint in Gesualdo’s musical language, the expressive dissonances and chromaticisms, the very conscious use of word painting and of symbolic numbers in his religious pieces, “Such a collection of codes […] paves the way for a more intensive examination of the Passion message” halfway between liturgy and multimedia.[109]

In fact, Glenn Watkins suggests another parallel between Gesualdo’s religious music and the Perdono of 1609 from a close reading of the title page of Tenebrae Resposoria (or “Responsory to Darkness for Holy Week”), published in 1611 by Giovanni Giacomo Carlino in Gesualdo’s palace:[110]

“Here, uniquely in his lifetime, the Prince of Venosa not only signed his work with his name but implicitly signalled the connection of its contents to the worlds of music, literature, and art. And art? Clearly this music and text were specifically intended to be sung in a location involving two extremely personal commissions, one each of architecture and of painting: the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie and the altarpiece, Il perdono.”[111]

The twentieth century

In his opera, La terribile e spaventosa storia del Principe di Venosa e della bella Maria (“The terrible and frightful story of the Prince of Venosa and the beautiful Maria”), composed in 1999 for the Sicilian Puppet Opera, Salvatore Sciarrino concludes with a song per finire, “written in a decidedly pop mode,”[112] in which he clearly alludes to the Perdono di Gesualdo, and to its composition between heaven and hell:[113]

Gesualdo a Venosa |

Gesualdo of Venosa |

A partial reproduction of the Perdono, showing the composer, St. Charles Borromeo, Mary Magdalene, and the winged child of purgatory, was used as the CD cover-art for the release of the second book of the Sacrae Cantiones, reconstructed in 2013 by the English composer and musicologist James Wood on the occasion of the 400th anniversary of Gesualdo’s death.

Notes

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 39

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 97

- ↑ Morrier 2003, pp. 97–98

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 39

- ↑ Gray & Heseltine 1926, p. 41

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 39

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 97

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 128

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 98

- ↑ Morrier 2003, pp. 98–99

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 99

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 65

- ↑ Watkins 2010, pp. 65–66

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 324

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 98

- ↑ Vaccaro 1998, p. 162

- ↑ Abbate 2001, p. 240

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 65

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 63

- ↑ Watkins 2010, pp. 64–65

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 66

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 97

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 13

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 148

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 14

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 66

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 324

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 66

- ↑ Watkins 2010, pp. 66–67

- ↑ Gray & Heseltine 1926, p. 42

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 66

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 67

- ↑ Viatte 1988, p. 35

- ↑ Griswold 1994, p. 45

- ↑ Abbate 2001, p. 240

- ↑ Abbate 2001, p. 240

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 225

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 128

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 67

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 67

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 104

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 63

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 309

- ↑ Gray & Heseltine 1926, p. 42

- ↑ Gray & Heseltine 1926, p. 43

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 309

- ↑ Watkins 2010, pp. 309–310

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 129

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 311

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 312

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 66

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 66

- ↑ Gray & Heseltine 1926, p. 42

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 128

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 66

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 65

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, pp. 128–129

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 146

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, pp. 150–151

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 68

- ↑ Watkins 1973, p. 83

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 68

- ↑ De Courcelles 1999, p. 87

- ↑ Ferretti o.p. 1998, p. 133

- ↑ Ferretti o.p. 1998, p. 168

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 68

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 68

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 324

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 68

- ↑ Green 2001, p. 135

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 325

- ↑ Gray & Heseltine 1926, p. 41

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 68

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 100

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 99

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 37

- ↑ Brantôme 1972, pp. 12–13

- ↑ Morrier 2003, pp. 66–67

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 32

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 65

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 76

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 38

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 15

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 150

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 99

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 22

- ↑ Gray & Heseltine 1926, pp. 40–41

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 233

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 348

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 121

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 99

- ↑ Morrier 2003, pp. 99–100

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 100

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, pp. 76–77

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 101

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 67

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 102

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 100

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 109

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 110

- ↑ Morrier 2003, pp. 109–110

- ↑ Morrier 2003, p. 111

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 63

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 134

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 69

- ↑ Watkins 2010, pp. 69–70

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 71

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 73

- ↑ Deutsch 2010, p. 132

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 76

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 228

- ↑ Watkins 2010, p. 229

Further reading and external links

- Abbate, Francesco (2001). Storia dell'arte nell'Italia meridionale, vol.3. Éditions Donzeli. ISBN 978-8-879-89653-5.

- Brantôme, Pierre, seigneur de (1972). Vies des dames galantes. Jean de Bonnot.

- de Courcelles, Dominique (1999). Le " Dialogue " de Catherine de Sienne. CERF. ISBN 2-204-06270-7.

- Deutsch, Catherine (2010). Carlo Gesualdo. Bleu nuit. ISBN 978-2-35884-012-5.

- Ferretti o.p., Mgr Lodovio (1998). Catherine de Sienne. Éditions Cantagalli.

- Gray, Cecil; Heseltine, Philip (1926). Carlo Gesualdo: musician and murderer. Trubner & Co. ISBN 978-1-275-49010-9.

- Green, Eugène (2001). La Parole baroque. Desclée de Brouwer. ISBN 2-220-05022-X.

- Griswold, William (1994). Sixteenth-century Italian Drawings in New York Collections. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-870-99688-7.

- Morrier, Denis (2003). Carlo Gesualdo. Fayard. ISBN 2-213-61464-4.

- Vaccaro, Antonio (1998). Carlo Gesualdo, principe de Venosa: L'uomo e i tempi. Osanna Edizioni. ISBN 978-8-881-67197-7.

- Viatte, Françoise (1988). Dessins toscans, xvie siècle-xviiie siècle. Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux. ISBN 978-2-711-82137-2.

- Watkins, Glenn (1973). Gesualdo: The Man and his Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816197-2.

- Watkins, Glenn (2010). The Gesualdo Hex: Music, Myth, and Memory. W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-07102-3.