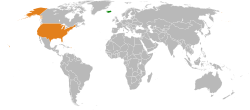

Iceland–United States relations

| |

Iceland |

United States |

|---|---|

Iceland–United States relations are bilateral relations between the Republic of Iceland and the United States of America. Both Iceland and the U.S. are NATO allies.

According to the 2012 U.S. Global Leadership Report, 17% of Icelanders approve of U.S. leadership, with 25% disapproving and 58% uncertain.[1]

Overview

The United States has maintained an interest in Iceland since the mid-1800s. In 1868, U.S. Department of State under William H. Seward authored a report that contemplated the purchase of Iceland from Denmark.[2]

The United States military established a presence in Iceland and around its waters after the Nazi occupation of Denmark (even before the U.S. entered World War II) in order to deny Nazi Germany access to its strategically important location (which would have been considered a threat to the Western Hemisphere).

The United States was the first country to recognize Icelandic independence from Denmark in June 1944, union with Denmark under a common king, and German and British occupation during World War II. Iceland is a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) but has no standing military of its own. The United States and Iceland signed a bilateral defense agreement in 1951, which stipulated that the U.S. would make arrangements for Iceland's defense on behalf of NATO and provided for basing rights for U.S. forces in Iceland; the agreement remains in force, although U.S. military forces are no longer permanently stationed in Iceland.

In 2006, the U.S. announced it would continue to provide for Iceland's defense but without permanently basing forces in the country. That year, Naval Air Station Keflavik closed and the two countries signed a technical agreement on base closure issues (e.g., facilities return, environmental cleanup, residual value) and a "joint understanding" on future bilateral security cooperation (focusing on defending Iceland and the North Atlantic region against emerging threats such as terrorism and trafficking). The United States also worked with local officials to mitigate the impact of job losses at the Air Station, notably by encouraging U.S. investment in industry and tourism development in the Keflavik area. Cooperative activities in the context of the new agreements have included joint search and rescue, disaster surveillance, and maritime interdiction training with U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard units; and U.S. deployments to support the NATO air surveillance mission in Iceland.

The U.S.–Icelandic relationship is founded on cooperation and mutual support. The two countries share a commitment to individual freedom, human rights, and democracy. U.S. policy aims to maintain close, cooperative relations with Iceland, both as a NATO ally interested in the shared objectives of enhancing world peace; respect for human rights; economic development; arms control; and law enforcement cooperation, including the fight against terrorism, narcotics, and human trafficking. The United States and Iceland work together on a wide range of issues from enhancing peace and stability in Afghanistan (Iceland is part of the ISAF coalition), to harnessing new green energy sources, to ensuring peaceful cooperation in the Arctic.

Economic relations

Both countries are part of the United Nations. Not only that, but the United States seeks to strengthen bilateral economic and trade relations. Most of Iceland's exports go to the European Union and the European Free Trade Association countries, followed by the United States and Japan. The U.S. is one of the largest foreign investors in Iceland, primarily in the aluminum sector. The United States and Iceland signed a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement in 2008.

Iceland's membership in international organizations

Iceland's ties with other Nordic states, the United States, and other NATO member states are particularly close. Iceland and the United States belong to a number of the same international organizations, including the United Nations, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Arctic Council, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and World Trade Organization.

Diplomatic visits

Only two U.S. presidents have visited Iceland whilst in office: Richard Nixon in 31 May-1 June 1973 and Ronald Reagan in 9-12 October 1986. President Richard Nixon was the first U.S. president to visit Iceland when he visited on 31 May - 1 June 1973. Reagan attended the Reykjavík Summit in 9-12 October 1986.[3]

Numerous other U.S. dignitaries have visited Iceland. First Lady Hillary Clinton spoke at a conference on Women and Democracy in Reykjavik in October 1999. She returned to Iceland as a U.S. senator in August 2004 on a fact-finding trip that also included her husband, former President Bill Clinton, and Senator John McCain. Secretary of State Colin Powell attended a NATO summit in Iceland in May 2002, and his successor, Condoleezza Rice, visited the country in May 2008.

The U.S. maintains an embassy in Reykjavik, Iceland.

Icelandic diplomats have also visited the United States on several occasions. Icelandic President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson attended a technology summit hosted by Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin in October 2007. He also met with Maine Gov. Paul LePage at an international trade summit in Portland, Maine in May 2013.

On May 13, 2016, President Barack Obama hosted a summit and state dinner for Nordic leaders from Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. Among the attendees from the Icelandic delegation were Prime Minister Sigurður Ingi Jóhannsson and the Icelandic Ambassador to the U.S., former Prime Minister Geir Haarde.

U.S. embassy in Iceland

Principal U.S. officials include:

- Ambassador—Robert C. Barber

- Charge D'Affairs–Paul O'Friel

- Deputy Chief of Mission—Neil Klopfenstein

- Political Officer—Brad Evans

- Economic/Commercial Officer—Fiona Evans

- Management Officer—Richard Johnson

- Information Management Officer—Ted Cross

- Public Affairs Officer—Robert Domaingue

- Consular Officer—Amiee McGimpsey

- Regional Security Officer—Peter A. Dinoia

Embassy of Iceland in the U.S.

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of State website http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/index.htm (Background Notes).

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of State website http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/index.htm (Background Notes).

- ↑ U.S. Global Leadership Project Report - 2012 Gallup

- ↑ Andersen, Anna (April 20, 2015). "That Time The United States Was Thinking Of Buying Iceland". The Reykjavík Grapevine. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ↑ Lab, Digital Scholarship. "The Executive Abroad". dsl.richmond.edu. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iceland – United States relations. |

- http://iceland.usembassy.gov/

- http://www.iceland.org/us/

- https://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/3396.htm

- http://country-facts.findthedata.com/compare/1-165/United-States-vs-Iceland

.svg.png)