Ibn Qudamah

| Imam Ibn Qudāmah | |

|---|---|

|

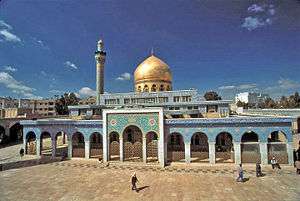

A 2010 photograph of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, where Ibn Qudamah frequently taught and prayed | |

| Jurisconsult, Theologian, Mystic; Shaykh of Islam, Champion of Hanbalism, Prince of the Qadiriyya Saints, Great Master of Hanbalite Law | |

| Venerated in | All of Sunni Islam, but particularly in the Hanbali school (Salafi Sunnis honor rather than venerate him). |

| Major shrine | Tomb of Imam Ibn Qudāmah, Damascus, Syria |

| Ibn Qudāmah | |

|---|---|

| Title | Sheikh ul-Islam |

| Born |

AH 541 (1146/1147)/Jan.-Feb. 1147 Jamma'in, Nablus, Palestine |

| Died |

1st Shawwal, 620 AH/7 July 1223 (aged 79) Damascus, Ayyubid dynasty, Syria |

| Region | Syrian scholar |

| Occupation | Islamic Scholar, Muhaddith, Muslim Jurist |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Sunni |

| Jurisprudence | Hanbali[1] |

| Creed | Athari[2] |

| Main interest(s) | Fiqh, Sufism |

| Notable work(s) |

al-ʿUmda al-Mug̲h̲nī |

| Sufi order | Qadiriyya |

|

Influenced by

| |

|

Influenced

| |

Ibn Qudāmah al-Maqdīsī Muwaffaq al-Dīn Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh b. Aḥmad b. Muḥammad (Arabic ابن قدامة, Ibn Qudāmah; 1147 - 7 July 1223), often referred to as Ibn Qudamah or Ibn Qudama for short, was a Sunni Muslim ascetic, jurisconsult, traditionalist theologian, and religious mystic.[4] Having authored many important treatises on jurisprudence and religious doctrine, including one of the standard works of Hanbali law, the revered al-Mug̲h̲nī,[5] Ibn Qudamah is highly regarded in Sunnism for being one of the most notable and influential thinkers of the Hanbali school of orthodox Sunni jurisprudence.[6] Within that school, he is one of the few thinkers to be given the honorific epithet of Shaykh of Islam, which is a prestigious title bestowed by Sunnis on some of the most important thinkers of their tradition.[6] A proponent of the classical Sunni position of the "differences between the scholars being a mercy," Ibn Qudamah is famous for having said: "The consensus of the Imams of jurisprudence is an overwhelming proof and their disagreement is a vast mercy."[7]

Life

Ibn Qudamah was born in Palestine in Jammain,[4] a town near Jerusalem (Bayt al-Maqdīs in the Arabic vernacular, whence his extended name), in 1147[6] to the revered Hanbali preacher and mystic Aḥmad b. Muḥammad b. Qudāmah (d. 1162), "a man known for his asceticism" and in whose honor "a mosque was [later] built in Damascus."[6][8] Having received the first phase of his education in Damascus,[4] where he studied the Quran and the hadith extensively,[4] Ibn Qudamah made his first trip to Baghdad in 1166,[6] in order to study law and Sufi mysticism[6] under the tutelage of the renowned Hanbali mystic and jurist Abdul-Qadir Gilani (d. ca. 1167),[6] who would go onto become one of the most widely-venerated saints in all of Sunni Islam.[6] Although Ibn Qudamah's "discipleship was cut short by the latter’s death ... [the] experience [of studying under Abdul-Qadir Gilani] ... had its influence on the young" scholar,[6] "who was to reserve a special place in his heart for mystics and mysticism" for the rest of his life.[6]

Ibn Qudamah's first stay in Baghdad lasted four years, during which time he is also said to have written an important work criticizing what he deemed to be the excessive rationalism of Ibn Aqil (d. 1119), entitled Taḥrīm al-naẓar fī kutub ahl al-kalām (The Censure of Rationalistic Theology).[6] During this sojourn in Baghdad, Ibn Qudamah studied hadith under numerous teachers, including three female hadith masters, namely Khadīja al-Nahrawāniyya (d. 1175), Nafīsa al-Bazzāza (d. 1168), and Shuhda al-Kātiba (d. ca. 1175).[9] In turn, all these various teachers gave Ibn Qudamah the permission to begin teaching the principles of hadith to his own students, including important female disciples such as Zaynab bint al-Wāsiṭī (d. ca. 1240).[9] Ibn Qudamah visited Baghdad again in 1189 and 1196, making his pilgrimage to Mecca the previous year in 1195, before finally settling down in Damascus in 1197,[6] which he only left in 1205 to fight in the army of Saladin against the Franks, "particularly in the conquest of Jerusalem, which occurred that year."[6] Ibn Qudamah died on Saturday, the Day of Eid al-Fitr, on July 7th, 1223.[6]

Views

God

In theological creed, Ibn Qudamah was one of the primary proponents of the Athari school of Sunni theology,[6][10] which held that overt theological speculation was spiritually detrimental and supported drawing theology exclusively from the two sources of the Quran and the hadith.[6] Regarding theology, Ibn Qudamah famously said: "We have no need to know the meaning of what God—Exalted is He—intended by His attributes—He is Great and Almighty. No deed is intended by them. No obligation is linked to them except belief in them. Belief in them is possible without knowing their meaning."[11][12] According to one scholar, it is evident that Ibn Qudamah "completely opposed discussion of theological matters and permitted no more than repeating what was said about God in the data of revelation."[13] In other words, Ibn Qudamah rejected "any attempt to link God’s attributes to the referential world of ordinary human language,"[11] which has led some scholars to describe Ibn Qudamah's theology as "unreflective traditionalism,"[14] that is to say, as a theological point of view which purposefully avoided any type of speculation or reflection upon the nature of God.[14] Ibn Qudamah's attitude towards theology was challenged by certain later Hanbali thinkers like Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 1328), who broke with this type of "unreflective traditionalism" in order to engage "in [bold and unprecedented] interpretation[s] of the meanings of God’s attributes."[14]

Heresy

Ibn Qudamah seems to have been a formidable opponent of heresy in Islamic practice, as is evidenced by his famous words: "There is nothing outside of Paradise but hell-fire; there is nothing outside of the truth but error; there is nothing outside of the Way of the Prophet but heretical innovation."[15]

Intercession

Ibn Qudamah appears to have been a supporter of seeking the intercession of the prophet Muhammad in personal prayer, for he approvingly cites the famous prayer attributed to Ibn Hanbal (d. 855): "O God! I am turning to Thee with Thy Prophet, the Prophet of Mercy. O Muhammad! I am turning with you to my Lord for the fulfillment of my need."[16][17] Ibn Qudama also relates that which al-’Utbiyy narrated concerning one's visitation to the grave of Muhammad in Medina:

I was sitting by the grave of the Prophet, peace and blessings be upon him, when a bedouin man [a‘rābī] entered and said, “Peace be upon you, oh Messenger of God. I have heard God say [in the Qur’an], ‘Had they come to you [the Prophet] after having done injustice to themselves [sinned] and asked God for forgiveness and [additionally had] the Messenger asked for forgiveness on their behalf, they would have found God to be oft-turning [in repentance] and merciful.’[18] And I have come to you seeking forgiveness for my sin[s], and seeking your intercession near God.” He [the bedouin man] then said the following poem:

O he who is the greatest of those buried in the grandest land,

[Of] those whose scent has made the valley and hills fragrant,

May my life be sacrificed for the grave that is your abode,

Where chastity, generosity and nobility reside!

Al-’Utbiyy then narrates that he fell asleep and saw the Prophet in a dream and was informed that the bedouin man had indeed been forgiven.[19][20]

After quoting the above event, Ibn Qudamah explicitly recommends that Muslims should use the above prayer when visiting the Prophet.[21] He thus approves of asking the Prophet for his intercession even after his earthly death.[21]

Mysticism

As is attested to by numerous sources, Ibn Qudamah was a devoted mystic and ascetic of the Qadiriyya order of Sufism,[6] and reserved "a special place in his heart for mystics and mysticism" for the entirety of his life.[6] Having inherited the "spiritual mantle" (k̲h̲irqa) of Abdul-Qadir Gilani prior to the renowned spiritual master's death, Ibn Qudamah was formally invested with the authority to initiate his own disciples into the Qadiriyya tariqa.[6] Ibn Qudamah later passed on the initiatic mantle to his cousin Ibrāhīm b. ʿAbd al-Wāḥid (d. 1217), another important Hanbali jurist, who became one of the primary Qadiriyya spiritual masters of the succeeding generation.[6] According to some classical Sufi chains, another one of Ibn Qudamah's major disciples was his nephew Ibn Abī ʿUmar Qudāmah (d. 1283), who later bestowed the k̲h̲irqa upon Ibn Taymiyyah, who, as many recent academic studies have shown, actually appears to have been a devoted follower of the Qadiriyya Sufi order in his own right, despite his criticisms of several of the most widespread, orthodox Sufi practices of his day and, in particular, of the philosophical influence of the Akbari school of Ibn Arabi.[22][23][24] Due to Ibn Qudamah's public support for the necessity of Sufism in orthodox Islamic practice, he gained a reputation for being one of "the eminent Sufis" of his era.[25]

Relics

Ibn Qudamah supported using the relics of Muhammad for the deriving of holy blessings,[26] as is evident from his approved citing, in al-Mug̲h̲nī 5:468, of the case of Abdullah ibn Umar (d. 693), whom he records as having placed "his hand on the seat of the Prophet's minbar ... [and] then [having proceeded to] wipe his face with it."[26] This view was not novel or even unusual in any sense,[26] as Ibn Qudamah would have found established support for the use of relics in the Quran, hadith, and in Ibn Hanbal's well-documented love for the veneration of Muhammad's relics.[26]

Saints

Ibn Qudamah staunchly criticized all who questioned or rejected the existence of saints, the veneration of whom had become an integral part of Sunni piety by the time period[27] and which he "roundly endorsed."[28] As scholars have noted, Hanbali authors of the period were "united in their affirmation of sainthood and saintly miracles,"[27] and Ibn Qudamah was no exception.[27] Thus, Ibn Qudamah vehemently criticized what he perceived to be the rationalizing tendencies of Ibn Aqil for his attack against the veneration of saints, saying: "As for the people of the Sunna who follow the traditions and pursue the path of the righteous ancestors, no imperfection taints them, not does any disgrace occur to them. Among them are the learned who practise their knowledge, the saints and the righteous men, the God-fearing and pious, the pure and the good, those who have attained the state of sainthood and the performance of miracles, and those who worship in humility and exert themselves in the study of religious law. It is with their praise that books and registers are adorned. Their annals embellish the congregations and assemblies. Hearts become alive at the mention of their life histories, and happiness ensues from following their footsteps. They are supported by religion; and religion is by them endorsed. Of them the Quran speaks; and the Quran they themselves express. And they are a refuge to men when events afflict them: for kings, and others of lesser rank, seek their visits, regarding their supplications to God as a means of obtaining blessings, and asking them to intercede for them with God."[28]

See also

References

- ↑ A.C. Brown, Jonathan (2014). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oneworld Publications. p. 63. ISBN 978-1780744209.

- ↑ Halverson, Jeffry R. (2010). Theology and Creed in Sunni Islam: The Muslim Brotherhood, Ash'arism, and Political Sunnism. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 37.

- 1 2 Calder, Norman; Mojaddedi, Jawid; Rippin, Andrew (24 Oct 2012). Classical Islam: A Sourcebook of Religious Literature. Routledge. p. 185. ISBN 190688417X.

- 1 2 3 4 Lewis, B.; Menage, V.L.; Pellat, Ch.; Schacht, J. (1986) [1st. pub. 1971]. Encyclopaedia of Islam (New Edition). Volume III (H-Iram). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. p. 842. ISBN 9004081186.

- ↑ Al-A'zami, Muhammad Mustafa (2003). The History of The Qur'anic Text: From Revelation to Compilation: A Comparative Study with the Old and New Testaments. UK Islamic Academy. p. 188. ISBN 978-1872531656.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Makdisi, G., “Ibn Ḳudāma al-Maḳdīsī”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs.

- ↑ Ibn Qudamah, Lam‘at al-I‘tiqad, trans. G. F. Haddad

- ↑ Nuʿaymī, Dāris, ii, 354

- 1 2 Asma Sayeed, Women and Transmission of Religious Knowledge in Islam (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 170

- ↑ Muwaffaq al-Dīn Ibn Qudāma al-Maqdisi, Ta!hrīm al-na)zar fī kutub al-kalām, ed. Abd al-Ra!hmān b. Mu!hammad Saīd Dimashqiyya (Riyadh: Dār ālam al-kutub, 1990); translated into English by George Makdisi, Ibn Qudāma’s Censure of Speculative Theology (London: Luzac, 1962)

- 1 2 Jon Hoover, Ibn Taymiyya's Theodicy of Perpetual Optimism (Leiden: Brill, 2007), p. 53

- ↑ Waines, David (2003). An Introduction to Islam. Cambridge University Press. p. 122. ISBN 0521539064.

- ↑ Jon Hoover, Ibn Taymiyya's Theodicy of Perpetual Optimism (Leiden: Brill, 2007), p. 19

- 1 2 3 Jon Hoover, Ibn Taymiyya's Theodicy of Perpetual Optimism (Leiden: Brill, 2007), p. 236

- ↑ John B. Henderson, The Construction of Orthodoxy and Heresy (New York: SUNY Press, 1998), epilogue

- ↑ Gibril F. Haddad, The Four Imams and Their Schools (London: Muslim Academic Trust, 2007), p. 322 [trans slightly revised].

- ↑ Ibn Quduma, Wasiyya al-Muwaffaq Ibn Quduma al-Maqdisi, p. 93

- ↑ Qur'an, 4:64

- ↑ Zargar, Cameron (2014). The Hanbali and Wahhabi Schools of Thought As Observed Through the Case of Ziyārah. The Ohio State University. pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Ibn Qudāmah, Abū Muḥammad, Al-Mughnī, (Beirut: Bayt al-Afkār al-Dawliyyah, 2004), p 795.

- 1 2 Zargar, Cameron (2014). The Hanbali and Wahhabi Schools of Thought As Observed Through the Case of Ziyārah. The Ohio State University. p. 29.

- ↑ Makdisi, 'Ibn Taymiya: a Sufi of the Qadiriya order', American Journal of Arabic Studies 1, part 1 (1973), pp 118-28

- ↑ Spevack, Aaron (2014). The Archetypal Sunni Scholar: Law, Theology, and Mysticism in the Synthesis of Al-Bajuri. State University of New York Press. p. 91. ISBN 143845371X.

- ↑ Rapoport, Yossef; Ahmed, Shahab (2010-01-01). Ibn Taymiyya and His Times. Oxford University Press. p. 334. ISBN 9780195478341.

- ↑ Najm al-Dīn al-Ṭūfī, al-Ta‘līq ‘alā al-Anājīl al-arba‘a wa-al-ta‘līq ‘alā al-Tawrāh wa-‘alā ghayrihā min kutub al-anbiyā’, 383, tr. L. Demiri, Muslim Exegesis of the Bible in Medieval Cairo, p. 16

- 1 2 3 4 Gibril F. Haddad, The Four Imams and Their Schools (London: Muslim Academic Trust, 2007), p. 322

- 1 2 3 Ahmet T. Karamustafa, Sufism: The Formative Period (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), pp. 131-132

- 1 2 Ahmet T. Karamustafa, Sufism: The Formative Period (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), p. 132

Further reading

- H. Laoust, Le Précis de Droit d’Ibn Qudāma, Beirut 1950

- idem., "Le Ḥanbalisme sous le califat de Baghdad," in REI, xxvii (1959), 125-6

- G. Makdisi, Kitāb at-Tauwābīn “Le Livre des Pénitents” de Muwaffaq ad-Dīn Ibn Qudāma al-Maqdisī, Damascus 1961

- idem., Ibn Qudāma’s censure of speculative theology, London 1962

External links

| Arabic Wikisource has original text related to this article: |