Telugu language

| Telugu | |

|---|---|

| తెలుగు | |

| |

| Pronunciation | IPA: [t̪el̪uɡu] |

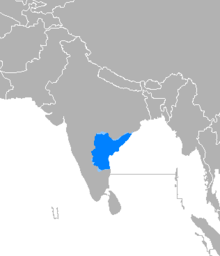

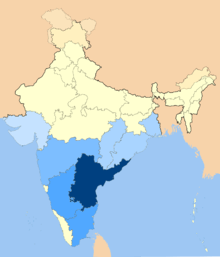

| Native to | India |

| Region | Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Yanam (Puducherry) and neighbouring states |

| Ethnicity | Telugu people |

Native speakers | 79.2 million (2016)[1] |

|

Dravidian

| |

|

Telugu alphabet Telugu Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

te |

| ISO 639-2 |

tel |

| ISO 639-3 |

tel |

| Glottolog |

telu1262 Telugu[2]oldt1249 Old Telugu[3] |

| Linguasphere |

49-DBA-aa |

|

| |

Telugu (English: /ˈtɛlᵿɡuː/;[4] telugu [t̪el̪uɡu]) is a Dravidian language native to India. It stands alongside Hindi, English, and Bengali as one of the few languages with official status in more than one Indian state;[5] Telugu is the primary language in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and in the town of Yanam, Puducherry, and is also spoken by significant minorities in Karnataka (8.03%), Tamil Nadu (8.63%), Maharashtra (1.4%), Chhattisgarh (1%), Odisha (1.9%), the Andaman and Nicobar Islands (12.9%), and by the Sri Lankan Gypsy people. It is one of six languages designated a classical language of India by the Government of India.[6][7]

Telugu ranks third by the number of native speakers in India (74 million, 2001 census),[8] fifteenth in the Ethnologue list of most-spoken languages worldwide[9] and is the most widely spoken Dravidian language in the world. It is one of the twenty-two scheduled languages of the Republic of India.[10]Approximately 10,000 inscriptions exist in the Telugu language.[11]

Etymology

The speakers of the language call it "Telugu".[12] The older forms of the name include Teluṅgu, Tenuṅgu and Teliṅga.[13]

The etymology of Telugu is not certain. Some historical scholars have suggested a derivation from Sanskrit triliṅgam, as in Trilinga Desa, "the country of the three lingas".

Tradition holds that Shiva descended as a lingam on three mountains: Kaleshwaram, Srisailam, and Bhimeswaram, which are said to have marked the boundaries of the Trilinga Desa. Atharvana Acharya in the 13th century wrote a grammar of Telugu, calling it the "Trilinga grammar" (Trilinga Śabdānusāsana).[14] Appa Kavi in the 17th century explicitly wrote that "Telugu" was derived from Trilinga. Scholar Charles P. Brown comments that it was a "strange notion" as all the predecessors of Appa Kavi had no knowledge of such a derivation.[15]

Atharvana Acharya in the 13th century wrote a grammar of Telugu in Sanskrit, calling it the "Trilinga grammar" (Trilinga Śabdānusāsana) in this grammar it was stated that God Brahma created Telugu for an ancient and legendary king called Andhra Vishnu, who ruled Andhra Desa or Trlinga Desa from his capital Srikakulam, on the banks of river Krishna, and Telugu was the language of the land and people of Trilinga Desa.

George Abraham Grierson and other linguists doubt this derivation, holding rather that Telugu was the older term and Trilinga must be a later Sanskritisation of it.[16][17] If so the derivation itself must have been quite ancient because Triglyphum, Trilingum and Modogalingam are attested in ancient Greek sources, the last of which can be interpreted as a Telugu rendition of "Trilinga".[18]

Another view holds that tenugu is derived from the proto-Dravidian word ten– "south"[19] to mean "the people who lived in the south/southern direction" (relative to Sanskrit and Prakrit-speaking peoples). The name telugu then, is a result of 'n' -> 'l' alternation established in Telugu.[20][21]

Lost literature and grammar

According to the native tradition Telugu grammar has an ancient past. Sage Kanva was said to be the first grammarian of Telugu. A Rajeswara Sarma discussed the historicity and content of Kanva's grammar written in Sanskrit. He cited twenty grammatical aphorisms ascribed to Kanva, and concluded that Kanva wrote an ancient Telugu Grammar which was lost.[22]

History

According to the Russian linguist M. S. Andronov, Proto-South-Dravidian languages split from the Proto-Dravidian language between 1500 and 1000 BC.[23][24] According to linguist Bhadriraju Krishnamurti, Telugu, as a Dravidian language, descends from Proto-Dravidian, a proto-language. Linguistic reconstruction suggests that Proto-Dravidian was spoken around the third millennium BC, possibly in the region around the lower Godavari river basin in peninsular India. The material evidence suggests that the speakers of Proto-Dravidian were of the culture associated with the Neolithic societies of South India.[25]

A legend gives the Lepakshi town a significant place in the Ramayana — this was where the bird Jatayu fell, wounded after a futile battle against Ravana who was carrying away Sita. When Sri Rama reached the spot, he saw the bird and said compassionately, “Le Pakshi” — ‘rise, bird’ in Telugu. This indicates the presence of Telugu Language during Ramayana period.[26]

There is a mention of Telugu people or Telugu country in ancient Tamil literature as Telunka Nadu [27] (Land of Telugu people).

It has been argued that there is a historical connection between the civilizations of ancient southern Mesopotamia and ancient Telugu speaking peoples.[28]

Earliest records

Earliest Telugu words have been found in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh

One of the earliest (350BC-200BC) [29][30]inscribed coins yielding Telugu Prakritic names[31] were of the Pre-Satavahana kings found around Koti Lingala, Telangana - Gobadha,Sama gopa,Kamvaaya Siri,Siri Vaaya,Siri Naarana.Contemporary to Sama gopa, Mahatalavara[32] coins were found [Tala in Telugu means head (Talai in Tamil)]

These artefacts, antiquities and structures offered dates ranging in between the 5th century BC to the 2nd century BC representing the early Janapada, the Mauryan, pre-Satavahana (local kings) and Satavahana dynasties.[33]The sites yielded undecipherable pre-Mauryan Brahmi characters(500BC-300BC)[30]. This script is under study.

Andhra Pradesh's Bhattiprolu inscriptions considered to be post-Mauryan script(200BC) by most scholars [34][35][36]. Some scholars view that they are pre-Mauryan script but which is not yet crystallized.

Prakrit Inscriptions with some Telugu words dating back to 400 BC to 100 BC have been discovered in Bhattiprolu in the Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh.[37] The English translation of one inscription reads, "gift of the slab by venerable Midikilayakha".[38][39][40]

Dated between 200 BCE and 200 CE, a Prakrit work called Gāthā Saptaśatī written by Sathavahana King Hala, Telugu words like అత్త, వాలుంకి, పీలుఅ, పోట్టం, కిలించిఅః, అద్దాఏ, భోండీ, సరఅస్స, తుప్ప, ఫలహీ, వేంట, రుంప-రంప, మడహసరిఆ, వోడసుణఓ, సాఉలీ and తీరఏ have been used.[41]

Post-Ikshvaku period

The period from 575 AD to 1022 AD corresponds to the second phase of Telugu history, after the Andhra Ikshvaku period. This is evidenced by the first inscription that is entirely in Telugu, dated 575 AD, which was found in the Rayalaseema region and is attributed to the Renati Cholas, who broke with the prevailing custom of using Sanskrit and began writing royal proclamations in the local language. During the next fifty years, Telugu inscriptions appeared in Anantapuram and other neighboring regions.

Telugu was more influenced by Sanskrit and Prakrit during this period, which corresponded to the advent of Telugu literature. Telugu literature was initially found in inscriptions and poetry in the courts of the rulers, and later in written works such as Nannayya's Mahabharatam (1022 AD).[42] During the time of Nannayya, the literary language diverged from the popular language. It was also a period of phonetic changes in the spoken language.

Middle Ages

The third phase is marked by further stylization and sophistication of the literary language. During this period the split of the Telugu and Kannada alphabets took place.[43] Tikkana wrote his works in this script.

Vijayanagara Empire

The Vijayanagara Empire gained dominance from 1336 to the late 17th century, reaching its peak during the rule of Krishnadevaraya in the 16th century, when Telugu literature experienced what is considered its Golden Age.[42]

Delhi Sultanate and Mughal influence

With the exception of Coastal Andhra, a distinct dialect developed in the Telangana State and the parts of Rayalaseema region due to Persian/Arabic influence: the Delhi Sultanate of the Tughlaq dynasty was established earlier in the northern Deccan Plateau during the 14th century. In the latter half of the 17th century, the Mughal Empire extended further south, culminating in the establishment of the princely state of Hyderabad State by the dynasty of the Nizam of Hyderabad in 1724. This heralded an era of Persian influence on the Telugu language, especially Hyderabad State. The effect is also evident in the prose of the early 19th century, as in the Kaifiyats.[42]

In the princely Hyderabad State, the Andhra Mahasabha was started in 1921 with the main intention of promoting Telugu language, literature, its books and historical research led by Madapati Hanumantha Rao (the founder of the Andhra Mahasabha), Komarraju Venkata Lakshmana Rao (Founder of Library Movement in Hyderabad State), Suravaram Pratapareddy and others.

Colonial period

The 16th-century Venetian explorer Niccolò de' Conti, who visited the Vijayanagara Empire, found that the words in Telugu language end with vowels, just like those in Italian, and hence referred it as "The Italian of the East";[44] a saying that has been widely repeated.[45]

In the period of the late 19th and the early 20th centuries saw the influence of the English language and modern communication/printing press as an effect of the British rule, especially in the areas that were part of the Madras Presidency. Literature from this time had a mix of classical and modern traditions and included works by scholars like Gidugu Venkata Ramamoorty, Kandukuri Veeresalingam, Gurazada Apparao, Gidugu Sitapati and Panuganti Lakshminarasimha Rao.[42]

Since the 1930s, what was considered an elite literary form of the Telugu language, has now spread to the common people with the introduction of mass media like movies, television, radio and newspapers. This form of the language is also taught in schools and colleges as a standard.

Post-independence period

- Telugu is one of the 22 languages with official status in India.

- The Andhra Pradesh Official Language Act, 1966, declares Telugu the official language of the state that is currently divided into Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. This enactment was implemented by GOMs No 420 in 2005.[46][47]

- Telugu also has official language status in the Yanam district of the union territory of Puducherry.

- Telugu, along with Kannada, was declared as one of the classical languages of India in the year 2008.

- The fourth World Telugu Conference was organized in Tirupati in the last week of December 2012 and deliberated at length on issues related to Telugu language policy

- Telugu is the third most spoken native language in India after Hindi and Bengali.

Epigraphical Records

According to the famous Japanese Historian Noboru Karashima who once served as the President of the Epigraphical Society of India in 1985 calculated that there are approximately 10,000 inscriptions which exist in the Telugu language as of the year 1996 making it one of the most densely inscribed languages.[11] Telugu inscriptions are found in all the districts of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. They are also found in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Orissa, and Chhattisgarh.[48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58] [59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66]

Telugu Country Boundaries

Andhra is characterised as having its own mother tongue, and its territory has been equated with the extent of the Telugu language. The equivalence between the Telugu linguistic sphere and geographical boundaries of Andhra is also brought out in an eleventh century description of Andhra boundaries. Andhra, according to this text, was bounded in north by Mahendra mountain in the modern Ganjam District of Orissa and to the south by Kalahasti temple in Chittor District. But Andhra extended westwards as far as Srisailam in the Kurnool District, about halfway across the modern state. Page number-36.[67] According to other sources in the early sixteenth century, the northern boundary is Simhachalam and the southern limit is Tirupati or Tirumala Hill of the Telugu Country.[68][69][70][71][72][73]

Dialects

There are three major dialects: Telangana dialect, laced with Urdu words, spoken mainly in Telangana, Andhra dialect spoken in the eastern region of Khammam district of Telangana in addition to coastal districts of Andhra Pradesh, and finally Rayalaseema dialect spoken in the four Rayalaseema districts of Andhra Pradesh.[74]

Waddar, Chenchu, and Manna-Dora are all closely related to Telugu.[75] Dialects of Telugu are Berad, Dasari, Dommara, Golari, Kamathi, Komtao, Konda-Reddi, Salewari, Vadaga, Srikakula, Vishakhapatnam, East Godaveri, Rayalseema, Nellore, Guntur, Vadari and Yanadi.[76]

In Karnataka the dialect sees more influence of Kannada and is a bit different than what is spoken in Andhra. There are significant populations of Telugu speakers in the eastern districts of Karnataka viz. Bangalore Urban, Bellari, Chikballapur, Kolar.

In Tamil Nadu the Telugu dialect is classified into Salem, Coimbatore, Vellore, Tiruvannamalai and Madras Telugu dialects. It is also spoken in pockets of Virudhunagar, Tuticorin, Tirunelveli, Madurai, Theni, Madras (Chennai) and Thanjavur districts.

Geographic distribution

Telugu is natively spoken in the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana and Yanam district of Puducherry. Telugu speaking migrants are also found in the neighboring states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, some parts of Jharkhand and the Kharagpur region of West Bengal in India. At 7.2% of the population, Telugu is the third-most-spoken language in the Indian subcontinent after Hindi and Bengali. In Karnataka, 7.0% of the population speak Telugu, and 5.6% in Tamil Nadu.[77]

The Telugu diaspora numbers more than 800,000 in the United States, with the highest concentration in Central New Jersey (Little Andhra[78]); Telugu speakers are found as well in Australia, New Zealand, Bahrain, Canada (Toronto), Fiji, Malaysia, Singapore, Mauritius, Myanmar, Ireland, South Africa, Trinidad and Tobago, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.

According to the M.L.A representing Hosur constituency, K.Gopinath, the Telugu population in Tamil Nadu is 40%.[79] Telugu is primary language in some parts of Chennai.

Phonology

The roman transliteration of the Telugu script is in National Library at Kolkata romanisation.

Telugu words generally end in vowels. In Old Telugu, this was absolute; in the modern language m, n, y, w may end a word. Atypically for a Dravidian language, voiced consonants were distinctive even in the oldest recorded form of the language. Sanskrit loans have introduced aspirated and murmured consonants as well.

Telugu does not have contrastive stress, and speakers vary on where they perceive stress. Most place it on the penultimate or final syllable, depending on word and vowel length.[80]

Vowels

Telugu features a form of vowel harmony wherein the second vowel in disyllabic noun and adjective roots alters according to whether the first vowel is tense or lax.[81] Also, if the second vowel is open (i.e., /aː/ or /a/), then the first vowel is more open and centralized (e.g., [mɛːka] 'goat', as opposed to [meːku] 'nail'). Telugu words also have vowels in inflectional suffixes that are harmonized with the vowels of the preceding syllable.[82]

| Vowels – అచ్చులు acculu | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /i/ ఇ i | /iː/ ఈ ī | /u/ ఉ u | /uː/ ఊ ū | ||

| /e/ ఎ e | /eː/ ఏ ē | /o/ ఒ o | /oː/ ఓ ō | ||

| /æː/ | /a/ అ a | /aː/ ఆ ā | |||

/æː/ only occurs in loan words.

Telugu has two diphthongs: /ai/ ఐ ai and /au/ ఔ au .

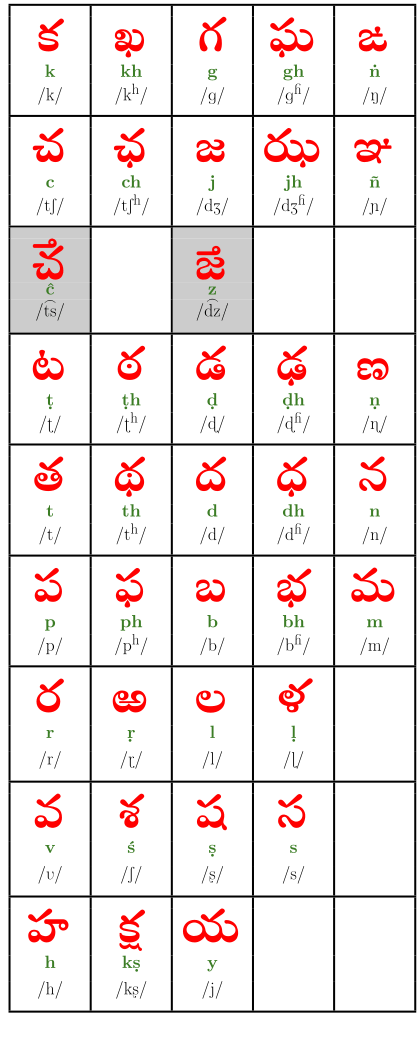

Consonants

The table below illustrates the articulation of the consonants.[83]

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Denti- alveolar |

Retroflex | "Palatal" | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | tenuis | /p/ ప pa | /t̪/ త ta | /ʈ/ ట ṭa | /t͡ʃ/ చ ca | /k/ క ka | |

| voiced | /b/ బ ba | /d̪/ ద da | /ɖ/ డ ḍa | /d͡ʒ/ జ ja | /ɡ/ గ ga | ||

| aspirated* | /pʰ/ ఫ pha | /t̪ʰ/ థ tha | /ʈʰ/ ఠ ṭha | /t͡ʃʰ/ ఛ cha | /kʰ/ ఖ kha | ||

| breathy voiced* | /bʱ/ భ bha | /d̪ʱ/ ధ dha | /ɖʱ/ ఢ ḍha | /d͡ʒʱ/ ఝ jha | /ɡʱ/ ఘ gha | ||

| Nasal | /m/ మ ma | /n̪/ న na | /ɳ/ ణ ṇa | ||||

| Fricative* | /f/ | /s̪/ స sa | /ʂ/ ష ṣa | /ɕ/ శ śa | /x/ హ ha | ||

| Approximant | central | /ʋ/ వ va | /j/ య ya | ||||

| lateral | /l̪/ ల la | /ɭ/ ళ ḷa | |||||

| Flap | /r̪/ రా ra | ||||||

*The aspirated and breathy-voiced consonants occur mostly in loan words, as do the fricatives apart from native /s̪/.

Grammar

The Telugu Grammar is called vyākaranam (వ్యాకరణం).

The first treatise on Telugu grammar, the Āndhra Śabda Cinṭāmaṇi, was written in Sanskrit by Nannayya, considered the first Telugu poet and translator, in the 11th century AD. This grammar followed patterns described in grammatical treatises such as Aṣṭādhyāyī and Vālmīkivyākaranam, but unlike Pāṇini, Nannayya divided his work into five chapters, covering samjnā, sandhi, ajanta, halanta and kriya. Every Telugu grammatical rule is derived from Pāṇinian concepts.

In the 19th century, Chinnaya Suri wrote a simplified work on Telugu grammar called Bāla Vyākaraṇam, borrowing concepts and ideas from Nannayya's grammar.

| Sentence | రాముడు బడికి వెళ్తాడు. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Words | రాముడు | బడికి | వెళ్తాడు. |

| Transliteration | rāmuḍu | baḍiki | veḷtāḍu |

| Gloss | Rama | to school | goes. |

| Parts | Subject | Object | Verb |

| Translation | Rama goes to school. | ||

This sentence can also be interpreted as 'Rama will go to school', depending on the context, but it does not affect the SOV order.

Inflection

Telugu nouns are inflected for number (singular, plural), gender (masculine, feminine, and neuter) and case (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, vocative, instrumental, and locative).[84]

Gender

Telugu has three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter.

Pronouns

Telugu pronouns include personal pronouns (the persons speaking, the persons spoken to, or the persons or things spoken about); indefinite pronouns; relative pronouns (connecting parts of sentences); and reciprocal or reflexive pronouns (in which the object of a verb is acted on by the verb's subject).

Telugu uses the same forms for singular feminine and neuter gender—the third person pronoun (అది /ad̪ɪ/) is used to refer to animals and objects.[85][86]

The nominative case (karta), the object of a verb (karma), and the verb are somewhat in a sequence in Telugu sentence construction. "Vibhakti" (case of a noun) and "pratyāyamulu" (an affix to roots and words forming derivatives and inflections) depict the ancient nature and progression of the language. The "Vibhaktis" of Telugu language " డు [ḍu], ము [mu], వు [vu], లు [lu]", etc., are different from those in Sanskrit and have been in use for a long time.

Vocabulary

Sanskrit influenced Telugu of Andhra and Telangana regions for about 1500 years; however, there is evidence that suggests an older influence. During the period 1000–1100 AD, Nannaya's re-writing of the Mahābhārata in Telugu (మహాభారతము) re-established its use, and it dominated over the royal language, Sanskrit. Telugu absorbed tatsamas from Sanskrit.[87]

The vocabulary of Telugu, especially in Telangana state, has a trove of Persian–Arabic borrowings, which have been modified to fit Telugu phonology. This was due to centuries of Turkic rule in these regions, such as the erstwhile kingdoms of Golkonda and Hyderabad (e.g., కబురు, /kaburu/ for Urdu /xabar/, خبر or జవాబు, /dʒavaːbu/ for Urdu /dʒawɑːb/, جواب).

Modern Telugu vocabulary can be said to constitute a diglossia because the formal, standardised version of the language is either lexically Sanskrit or heavily influenced by Sanskrit, is taught in schools, and is used by the government and Hindu religious institutions. However, everyday Telugu varies depending upon region and social status.

Writing system

The Telugu script is an abugida consisting of 60 symbols – 16 vowels, 3 vowel modifiers, and 41 consonants. Telugu has a complete set of letters that follow a system to express sounds.Telugu Writing is highly influenced by Kannada writing system expect some letters [88] The script is derived from the Brahmi Script like that many other Indian languages.[89] The Telugu script is written from left to right and consists of sequences of simple and/or complex characters. The script is syllabic in nature—the basic units of writing are syllables. Since the number of possible syllables is very large, syllables are composed of more basic units such as vowels (“accu” or “swaram”) and consonants (“hallu” or “vyanjanam”). Consonants in consonant clusters take shapes that are very different from the shapes they take elsewhere. Consonants are presumed pure consonants, that is, without any vowel sound in them. However, it is traditional to write and read consonants with an implied 'a' vowel sound. When consonants combine with other vowel signs, the vowel part is indicated orthographically using signs known as vowel “mātras”. The shapes of vowel “mātras” are also very different from the shapes of the corresponding vowels.

Historically, a sentence used to end with either a single bar । (“pūrna virāmam”) or a double bar ॥ (“dīrgha virāmam”); in handwriting, Telugu words were not separated by spaces. However, in modern times, English punctuation (commas, semicolon, etc.) have virtually replaced the old method of punctuation.[90]

| Consonants – hallulu (హల్లులు) |

|---|

|

Telugu has full-zero (anusvāra) ( ం ), half-zero (arthanusvāra or candrabindu) (ఁ) and visarga ( ః ) to convey various shades of nasal sounds. [la] and [La], [ra] and [Ra] are differentiated.[90]

Telugu has ĉ and ĵ, which are not represented in Sanskrit. Their pronunciation is similar to the 's' sound in the word treasure (i.e., the postalveolar voiced fricative) and 'z' sound in zebra (i.e., the alveolar voiced fricative), respectively.

Telugu Gunintālu (తెలుగు గుణింతాలు)

These are some examples of combining a consonant with different vowels.

క కా కి కీ కు కూ కృ కౄ కె కే కై కొ కో కౌ క్ కం కః

ఖ ఖా ఖి ఖీ ఖు ఖూ ఖృ ఖౄ ఖె ఖే ఖై ఖొ ఖో ఖౌ ఖ్ ఖం ఖః

Number system

Telugu has ten digits employed with the Hindu–Arabic numeral system. However, in modern usage, the Arabic numerals have replaced them.

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 0 | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ |

| sunna (Telugu form of Sanskrit word śūnyam) | okaṭi | reṁḍu | mūḍu | nālugu | aidu | āru | ēḍu | enimidi | tommidi |

Telugu is assigned Unicode codepoints: 0C00-0C7F (3072–3199).[91]

Literature

The Pre-Nannayya Period (before 1020 AD): In the earliest period Telugu literature existed in the form of inscriptions, precisely from 575 AD on-wards.

The Jain Literature Phase(850-1000 AD): Prabandha Ratnavali[1](1918) & Pre-Nannayya Chandassu (Raja Raja Narendra Pattabhisekha Sanchika) by Veturi Prabhakara Sastry talk about the existence of Jain Telugu literature during 850-1000AD.A verse from Telugu Jinendra Puranam by Padma Kavi(Pampa),a couple of verses from Telugu Adi Puranam by Sarvadeva and Kavijanasrayam (a Telugu Chandassu poetic guide for poets) affiliation to Jainism were discussed.

Historically,Vemulawada was a Jain knowledge hub and played a significant role in patronizing Jain literature and poets.1980s excavations around Vemulawada revealed and affirmed the existence of Telugu Jain literature.

Malliya Rechana - First Telugu Author (940AD) - [11] P.V.Parabrahma Sastry, Nidadavolu Venkata Rao [12] .P.V.P Sastry also points out that many Jain works could have been destroyed[11] .Historical rivalry among Hinduism,Jainism and Buddhism is well known[13]

The Age of the Puranas (1020-1400AD) : This is the period of Kavi Trayam or Trinity of Poets. Nannayya, Tikkana and Yerrapragada (or Errana) are known as the Kavi Trayam.

Nannaya Bhattarakudu or Adi Kavi (1022–1063 AD) : Nannaya Bhattarakudu's (Telugu: నన్నయ) Andhra mahabharatam, who lived around the 11th century, is commonly referred to as the first Telugu literary composition (aadi kaavyam).[citation needed] Although there is evidence of Telugu literature before Nannaya, he is given the epithet Aadi Kavi ("the first poet"). Nannaya was the first to establish a formal grammar of written Telugu. This grammar followed the patterns which existed in grammatical treatises like Aṣṭādhyāyī and Vālmīkivyākaranam but unlike Pāṇini, Nannayya divided his work into five chapters, covering samjnā, sandhi, ajanta, halanta and kriya.[14] Nannaya completed the first two chapters and a part of the third chapter of the Mahabharata epic, which is rendered in the Champu style.[citation needed]

[15]===== Tikanna Somayaji (1205–1288 AD) ===== Nannaya's Andhra Mahabharatam was almost completed by Tikanna Somayaji (Telugu: తిక్కన సోమయాజి) (1205–1288) who wrote chapters 4 to 18.[citation needed]

Errapragada : Errapragada, (Telugu: ఎర్రాప్రగడ) who lived in the 14th century, finished the epic by completing the third chapter.[citation needed] He mimics Nannaya's style in the beginning, slowly changes tempo and finishes the chapter in the writing style of Tikkana.[citation needed] These three writers – Nannaya, Tikanna and Yerrapragada – are known as the Kavitraya ("three great poets") of Telugu. Other such translations like Marana’s Markandeya Puranam, Ketana’s Dasakumara Charita, Yerrapragada’s Harivamsam followed. Many scientific[relevant? ] works, like Ganitasarasangrahamu by Pavuluri Mallana and Prakirnaganitamu by Eluganti Peddana, were written in the 12th century.[16][full citation needed]

Baddena Bhupala (1220-1280AD) : Sumati Shatakam, which is a neeti ("moral"), is one of the most famous Telugu Shatakams.[citation needed] Shatakam is composed of more than a 100 padyalu (poems). According to many literary critics[who?] Sumati Shatakam was composed by Baddena Bhupaludu (Telugu: బద్దెన భూపాల) (CE 1220–1280). He was also known as Bhadra Bhupala. He was a Chola prince and a vassal under the Kakatiya empress Rani Rudrama Devi, and a pupil of Tikkana.[citation needed] If we assume that the Sumati Shatakam was indeed written by Baddena, it would rank as one of the earliest Shatakams in Telugu along with the Vrushadhipa Satakam of Palkuriki Somanatha and the Sarveswara Satakam of Yathavakkula Annamayya.[original research?] The Sumatee Shatakam is also one of the earliest Telugu works to be translated into a European language, as C. P. Brown rendered it in English in the 1840s.[citation needed]

In the Telugu literature Tikkana was given agraasana (top position) by many famous critics.

Paravastu Chinnayya Soori (1807–1861) is a well-known Telugu writer who dedicated his entire life to the progress and promotion of Telugu language and literature. Sri Chinnayasoori wrote the Bala Vyakaranam in a new style after doing extensive research on Telugu grammar. Other well-known writings by Chinnayasoori are Neethichandrika, Sootandhra Vyaakaranamu, Andhra Dhatumoola, and Neeti Sangrahamu.

Kandukuri Veeresalingam (1848–1919) is generally considered the father of modern Telugu literature.[92] His novel Rajasekhara Charitamu was inspired by the Vicar of Wakefield. His work marked the beginning of a dynamic of socially conscious Telugu literature and its transition to the modern period, which is also part of the wider literary renaissance that took place in Indian culture during this period. Other prominent literary figures from this period are Gurajada Appa Rao, Viswanatha Satyanarayana, Gurram Jashuva, Rayaprolu Subba Rao, Devulapalli Krishnasastri and Srirangam Srinivasa Rao, popularly known as Mahakavi Sri Sri. Sri Sri was instrumental in popularising free verse in spoken Telugu (vaaduka bhasha), as opposed to the pure form of written Telugu used by several poets in his time. Devulapalli Krishnasastri is often referred to as the Shelley of Telugu literature because of his pioneering works in Telugu Romantic poetry.

Viswanatha Satyanarayana won India's national literary honour, the Jnanpith Award for his magnum opus Ramayana Kalpavrikshamu.[93] C. Narayana Reddy won the Jnanpith Award in 1988 for his poetic work, Viswambara. Ravuri Bharadhwaja won the 3rd Jnanpith Award for Telugu literature in 2013 for Paakudu Raallu, a graphic account of life behind the screen in film industry.[94] Kanyasulkam, the first social play in Telugu by Gurajada Appa Rao, was followed by the progressive movement, the free verse movement and the Digambara style of Telugu verse. Other modern Telugu novelists include Unnava Lakshminarayana (Maalapalli), Bulusu Venkateswarulu (Bharatiya Tatva Sastram), Kodavatiganti Kutumba Rao and Buchi Babu.

Telugu support on digital devices

Telugu input, display, and support were initially provided on the Microsoft Windows platform. Subsequently, various browsers, office applications, operating systems, and user interfaces were localized for Windows and Linux platforms by vendors and free and open-source software volunteers. Telugu-capable smart phones were also introduced by vendors in 2013.[95]

See also

- Telugu language day

- Telugu people

- Telugu grammar

- List of Indian languages by total speakers

- List of Telugu-language television channels

- States of India by Telugu speakers

- Telugu language policy

References

- ↑ Telugu at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Telugu". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Old Telugu". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- ↑ Schools, Colleges called for a shutdown in Telugu states

- ↑ "Declaration of Telugu and Kannada as classical languages". Press Information Bureau. Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Government of India. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ↑ "Telugu gets classical status". Times of India. 1 October 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-11-04. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ "Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues – 2000". Census of India, 2001. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- ↑ "Statistical Summaries/ Summary by language size".

- ↑ "PART A Languages specified in the Eighth Schedule (Scheduled Languages)". Archived from the original on 2013-10-29.

- 1 2 Morrison, Kathleen D.; Lycett, Mark T. (1997). "Inscriptions as Artifacts: Precolonial South India and the Analysis of Texts" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. Springer. 4 (3/4): 218 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Rao & Shulman 2002, Chapter 2.

- ↑ Parpola, Asko (2015), The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization, Oxford University Press Incorporated, p. 167, ISBN 0190226927

- ↑ Chenchiah, P.; Rao, Raja M. Bhujanga (1988). A History of Telugu Literature. Asian Educational Services. p. 55. ISBN 978-81-206-0313-4.

- ↑ Brown, Charles P. (1839), "Essay on the Language and Literature of Telugus", Madras Journal of Literature and Science, Volume X, Vepery mission Press., p. 53

- ↑ Grierson, George A. (1967) [1906]. "Telugu". Linguistic Survey of India. Volume IV, Mundā and Dravidian languages. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 576. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ↑ Sekaram, Kandavalli Balendu (1973), The Andhras through the ages, Sri Saraswati Book Depot, p. 4,

The easier and more ancient "Telugu" appears to have been converted here into the impressive Sanskrit word Trilinga, and making use of its enormous presitge as the classical language, the theory wa sput forth that the word Trilinga is the morther and not the child.

- ↑ Caldwell, Robert (1856), A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian Family of Languages (PDF), London: Harrison, p. 64

- ↑ Telugu Basha Charitra. Hyderabad: Osmania University. 1979. pp. 6, 7.

- ↑ The Dravidian Languages – Bhadriraju Krishnamurti.

- ↑ Rao & Shulman 2002, Introduction.

- ↑

- ↑ "Indian Encyclopaedia – Volume 1", p. 2067, by Subodh Kapoor, Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd, 2002

- ↑ "Proto-Dravidian Info". lists.hcs.harvard.edu.

- ↑ ["https://lists.hcs.harvard.edu/mailman/listinfo/proto-dravidian "https://lists.hcs.harvard.edu/mailman/listinfo/proto-dravidian] Check

|url=value (help). Missing or empty|title=(help), - ↑

- ↑ "Bengal".

- ↑

- ↑ The Andhra Pradesh Journal of Archaeology, Volume 3, Issue 2. 1995.

- 1 2 Annual Report of Department of Archaeology & Musuems. 1981.

- ↑ The Indian Encyclopaedia.

- ↑ Comprehensive History and Culture of Andhra Pradesh.

- ↑ E, Siva Nagi Reddy (Feb 2017). "HansIndia,The Cultural Centre of Vijayawada and Amaravati.".

- ↑ Researches in Archaeology, History, and Culture in the New Millennium. 2004.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ K S, Ramachandra (1980). Archaeology of South India.

- ↑ Bhattiprolu. Fact pres. 2012.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Agrawal, D. P.; Chakrabarti, Dilip K. (1979), Essays in Indian protohistory, The Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies/B.R. Pub. Corp., p. 326

- ↑ The Hindu News: Telugu is 2,400 years old, says ASI "The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has joined the Andhra Pradesh Official Languages Commission to say that early forms of the Telugu language and its script indeed existed 2,400 years ago"

- ↑ Indian Epigraphy and South Indian Scripts, C. S. Murthy, 1952, Bulletins of the Madras Government Museum, New Series IV, General Section, Vol III, No. 4

- ↑ Buhler, G. (1894), Epigraphica Indica, Vol.2

- ↑

- 1 2 3 4 "APonline – History and Culture-Languages". aponline.gov.in.

- ↑ Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0-521-77111-0.

- ↑ Venetian merchant-traveler Niccolo de Conti coins the term "Italian of the East"

- ↑ Morris, Henry (2005). A Descriptive and Historical Account of the Godavery District in the Presideny of Madras. Asian Educational Services. p. 86. ISBN 978-81-206-1973-9.

- ↑ Rao, M. Malleswara (18 September 2005). "Telugu declared official language". The Hindu. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ↑ "APonline – History and Culture – History-Post-Independence Era". aponline.gov.in.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ [ https://books.google.co.in/books?id=n0gwfmPFTLgC&pg=PA209&dq=telugu+inscriptions+in+maharashtra&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj5iteQpbPUAhXDrI8KHf1hCfAQ6AEIMjAD#v=onepage&q=telugu%20inscriptions%20in%20maharashtra&f=false]

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Cynthia Talbot (20 September 2001). Precolonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra. Oxford University Press. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-19-803123-9.

- ↑ Velcheru Narayana Rao; David Shulman (2002). Classical Telugu Poetry: An Anthology. Univ of California Press. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-0-520-22598-5.

- ↑ International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics: IJDL. Department of Linguistics, University of Kerala. 2004.

- ↑ Ajay K. Rao (3 October 2014). Re-figuring the Ramayana as Theology: A History of Reception in Premodern India. Routledge. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-1-134-07735-9.

- ↑ S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar (1994). Evolution of Hindu Administrative Institutions in South India. Asian Educational Services. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-81-206-0966-2.

- ↑ Cynthia Talbot (2001). Precolonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra. Oxford University Press. pp. 195–. ISBN 978-0-19-513661-6.

- ↑ Sambaiah Gundimeda (14 October 2015). Dalit Politics in Contemporary India. Routledge. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-1-317-38104-4.

- ↑ Caffarel, Alice; Martin, J. R.; Matthiessen, Christian M. I. M. (2004). Language Typology: A Functional Perspective. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 434. ISBN 1-58811-559-3. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Teluguic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Telugu". Ethnologue. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ↑ "Census of India – DISTRIBUTION OF 10,000 PERSONS BY LANGUAGE". Censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ↑ Accessed June 17, 2017.

- ↑ "The Telugu man in the Tamil House". The Hindu. 30 December 2012.

- ↑ Lisker and Krishnamurti (1991), "Lexical stress in a 'stressless' language: judgments by Telugu- and English-speaking linguists." Proceedings of the XII International Congress of Phonetic Sciences (Université de Provence), 2:90–93.

- ↑ Wilkinson (1974:251)

- ↑ A Grammar of the Telugu Language, p. 295, Charles Philip Brown,

- ↑ Krishnamurti (1998), "Telugu". In Steever (ed.), The Dravidian Languages. Routledge. pp. 202–240, 260

- ↑ Charles Philip Brown (1857). A grammar of the Telugu language (2 ed.). Christian Knowledge Society's Press.

- ↑ Albert Henry Arden (1873). A progressive grammar of the Telugu language. Society for promoting Christian knowledge. p. 57. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Charles Philip Brown (1857). A grammar of the Telugu language (2 ed.). Christian Knowledge Society's Press. p. 39. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Ramadasu, G (1980). "Telugu bhasha charitra". Telugu academy

- ↑ Chenchiah, P.; Rao, Raja Bhujanga (1988). A History of Telugu Literature. Asian Educational Services. p. 18. ISBN 81-206-0313-3.

- ↑

- 1 2 Brown, Charles Philip (1857). A Grammar of the Telugu Language. London: W. H. Allen & Co. p. 5. ISBN 81-206-0041-X.

- ↑ United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names; United Nations Statistical Division (2007). Technical Reference Manual for the Standardization of Geographical Names. United Nations Publications. p. 110. ISBN 92-1-161500-3.

- ↑ Sarma, Challa Radhakrishna (1975). Landmarks in Telugu Literature. Lakshminarayana Granthamala. p. 30.

- ↑ Datta, Amaresh; Lal, Mohan (1991). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. p. 3294.

- ↑ George, K.M. (1992). Modern Indian Literature, an Anthology. Sahitya Akademi. p. 1121. ISBN 81-7201-324-8.

- ↑ "Samsung phones to support 9 Indian languages". thehindubusinessline.com.

Bibliography

- Albert Henry Arden, A Progressive Grammar of the Telugu Language (1873).

- Charles Philip Brown, English–Telugu dictionary (1852; revised ed. 1903;

- The Lingustic Legacy of Indo-Guyanese http://www.stabroeknews.com/2014/features/in-the-diaspora/04/21/linguistic-legacy-indian-guyanese/

- Languages of Mauritius https://mauritiusattractions.com/mauritius-languages-i-85.html

- Charles Philip Brown, A Grammar of the Telugu Language (1857)

- P. Percival, Telugu–English dictionary: with the Telugu words printed in the Roman as well as in the Telugu Character (1862, google books edition)

- Gwynn, J. P. L. (John Peter Lucius). A Telugu–English Dictionary Delhi; New York: Oxford University Press (1991; online edition).

- Uwe Gustafsson, An Adiwasi Oriya–Telugu–English dictionary, Central Institute of Indian Languages Dictionary Series, 6. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Language (1989).

- Rao, Velcheru Narayana; Shulman, David (2002), Classical Telugu Poetry: An Anthology, University of California Press

- Callā Rādhākr̥ṣṇaśarma, Landmarks in Telugu Literature: A Short Survey of Telugu Literature (1975).

- Wilkinson, Robert W. (1974). "Tense/lax vowel harmony in Telugu: The influence of derived contrast on rule application". Linguistic Inquiry. 5 (2): 251–270

External links

| Telugu edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Hints and resources for learning Telugu

- English to Telugu online dictionary

- 'Telugu to English' and 'English to Telugu' Dictionary

- Dictionary of mixed Telugu By Charles Philip Brown

- Origins of Telugu Script

- Online English – Telugu dictionary portal that includes many popular dictionaries

- Telugu literature online

- English–Telugu Dictionary