Ladin language

| Ladin | |

|---|---|

| Ladin | |

| |

| Native to | Italy – Dolomite Mountains, Non Valley |

| Region |

Trentino-South Tyrol Veneto |

Native speakers | 31,000 (2013)[1] |

| Dialects | |

| Official status | |

| Regulated by |

The office for Ladin language planning Ladin Cultural Centre Majon di Fascegn Istitut Ladin Micurà de Rü Istituto Ladin de la Dolomites |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

lld |

| Glottolog |

ladi1250[2] |

| Linguasphere |

51-AAA-l |

| Languages of South Tyrol. Majorities per municipality in 2011: | |

|---|---|

|

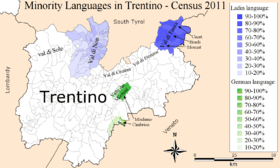

| Languages of Trentino. Percentage per municipality in 2011: | |

|---|---|

|

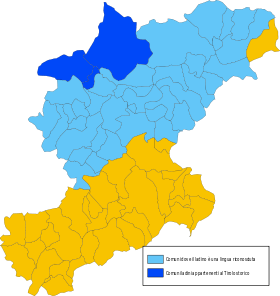

| Languages of the Province of Belluno. Recognized Ladin area | |

|---|---|

|

Ladin (/læˈdiːn/[3] or /ləˈdiːn/;[4] Ladin: Ladin, Italian: Ladino, German: Ladinisch) is a Romance language consisting of a group of dialects (which some consider part of a unitary Rhaeto-Romance language) mainly spoken in the Dolomite Mountains in Northern Italy in South Tyrol, the Trentino and the province of Belluno by the Ladin people. It exhibits similarities to Swiss Romansh and Friulian.

The precise extension of the Ladin language area is the subject of scholarly debates. A more narrow perspective includes only the dialects of the valleys around the Sella group, wider definitions comprise the dialects of adjacent valleys in the Province of Belluno and even dialects spoken in the northwestern Trentino.[5][6]

A standard written variety of Ladin (Ladin Dolomitan) has been developed by the Office for Ladin Language Planning as a common communication tool across the whole Ladin-speaking region,[7] but it is not popular among Ladin speakers.

Ladin should not be confused with Ladino (also called Judeo-Spanish), which, although also Romance, is derived from Old Spanish.

Geographic distribution

Ladin is recognized as a minority language in 54 Italian municipalities[8] belonging to the provinces of South Tyrol, Trentino and Belluno. It is not possible to assess the exact number of Ladin speakers, because only in the provinces of South Tyrol and Trentino are the inhabitants asked to identify their native language in the general census of the population, which takes place every ten years.

South Tyrol

In the 2011 census, 20,548 inhabitants of South Tyrol declared Ladin as their native language.[9] Ladin is an officially recognised language, taught in schools and used in public offices (in written as well as spoken form). The following municipalities of South Tyrol have a majority of Ladin speakers:

| Ladin name | Inhabitants | Ladin speakers |

|---|---|---|

| Badia | 3366 | 94.07% |

| Corvara | 1320 | 89.70% |

| La Val | 1299 | 97.66% |

| Mareo | 2914 | 92.09% |

| Urtijëi | 4659 | 84.19% |

| San Martin de Tor | 1733 | 96.71% |

| Santa Cristina Gherdëina | 1873 | 91.40% |

| Sëlva | 2664 | 89.74% |

| Kastelruth | 6465 | 15.37%[10] |

| Province total | 505,067[11] | 4.53% |

Trentino

In the 2011 census, 18,550 inhabitants of Trentino declared Ladin as their native language.[12] It is prevailing in the following municipalities of Trentino in the Fassa Valley, where Ladin is recognized as a minority language:

| Italian name | Ladin name | Inhabitants | Ladin speakers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campitello di Fassa | Ciampedel | 740 | 608 | 82.2% |

| Canazei | Cianacei | 1,911 | 1,524 | 79.7% |

| Mazzin | Mazin | 493 | 381 | 77.3% |

| Moena | Moena | 2,698 | 2,126 | 78.8% |

| Pozza di Fassa | Poza | 2,138 | 1,765 | 82.6% |

| Soraga | Sorega | 736 | 629 | 85.5% |

| Vigo di Fassa | Vich | 1,207 | 1,059 | 87.7% |

| Province total | 526,510 | 18,550 | 3.5% |

The Nones language in the Non Valley and the related Solandro language found in the Sole Valley are Gallo-Romance languages and often grouped together into a single linguistic unit due to their similarity. They are spoken in 38 municipalities, but have no official status. Their more precise classification is uncertain. Both dialects show a strong resemblance to Trentinian dialect and Eastern Lombard, and scholars debate whether they are Ladin dialects or not.

About 23% of the inhabitants from Val di Non and 1.5% from Val di Sole declared Ladin as their native language at the 2011 census. The number of Ladin speakers in those valleys amounts to 8,730, outnumbering the native speakers in the Fassa Valley.[13] In order to stress the difference between the dialects in Non and Fassa valleys, it has been proposed to distinguish between ladins dolomitiches (Dolomitic Ladinians) and ladins nonejes (Non Valley Ladinians) at the next census.[14]

Province of Belluno

As there is no linguistic census in the province of Belluno, the number of Ladin speakers can only be estimated. Around 3,000 speakers are estimated to live in the part of the province that was part of the County of Tyrol until 1918, and including the communes of Cortina d'Ampezzo, Colle Santa Lucia, Livinallongo del Col di Lana.

The provincial administration of Belluno has enacted to identify Ladin as a minority language in additional municipalities. Those are: Agordo, Alleghe, Auronzo di Cadore, Borca di Cadore, Calalzo di Cadore, Canale d'Agordo, Cencenighe Agordino, Cibiana di Cadore, Comelico Superiore, Danta di Cadore, Domegge di Cadore, Falcade, Forno di Zoldo, Gosaldo, La Valle Agordina, Lozzo di Cadore, Ospitale di Cadore, Perarolo di Cadore, Pieve di Cadore, Rivamonte Agordino, Rocca Pietore, San Nicolò di Comelico, San Pietro di Cadore, San Tomaso Agordino, San Vito di Cadore, Santo Stefano di Cadore, Selva di Cadore, Taibon Agordino, Vallada Agordina, Valle di Cadore, Vigo di Cadore, Vodo di Cadore, Voltago Agordino, Zoldo Alto, Zoppè di Cadore. Ladinity in the province of Belluno is more ethnic than linguistic. The varieties spoken by Ladin municipalities are Venetian alpine dialects, grammatically no different to those spoken in municipalities that did not declare themselves as Ladin.[15] Their language is called Ladino Bellunese.[16]

All Ladin dialects spoken in the province of Belluno, including those in the former Tyrolean territories, enjoy a varying degree of influence by Venetian.[17]

History

The name derives from Latin, because Ladin is originally a Vulgar Latin language left over from the Romanized Alps. Ladin is often attributed to be a relic of Vulgar Latin dialects associated with Rhaeto-Romance languages. Whether a proto-Romance language ever existed is controversially discussed amongst linguists and historians, a debate known as Questione Ladina. Starting in the 6th century, the Bavarii started moving in from the north, while from the south Gallo-Italic languages started pushing in, which further shrank the original extent of the Ladin area. Only in the more remote mountain valleys did Ladin survive among the isolated populations.

Starting in the very early Middle Ages, the area was mostly ruled by the County of Tyrol or the Bishopric of Brixen, both belonging to the realms of the Austrian Habsburg rulers. The area of Cadore was under the rule of the Republic of Venice. During the period of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and, after 1804, the Austrian Empire, the Ladins underwent a process of Germanization.

After the end of World War I in 1918, Italy annexed the southern part of Tyrol, including the Ladin areas. The Italian nationalist movement of the 19th and 20th centuries regarded Ladin as an "Italian dialect", a notion rejected by various Ladin exponents and associations,[19] despite their having been counted as Italians by the Austrian authorities as well. The programme of Italianization, professed by fascists such as Ettore Tolomei and Benito Mussolini, added further pressure on the Ladin communities to subordinate their identities to Italian. This included changing Ladin place names into the Italian pronunciation according to Tolomei's Prontuario dei nomi locali dell'Alto Adige.

Following the end of World War II, the Gruber-De Gasperi Agreement of 1946 between Austria and Italy introduced a level of autonomy for Trentino and South Tyrol, but did not include any provisions for the Ladin language. Only in the second autonomy statute for South Tyrol in 1972 was Ladin recognized as a partially official language.

Status

Ladin is officially recognised in Trentino and South Tyrol by provincial and national law. Italy signed the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages of 1991, but has not ratified it so far. The charter calls for minority rights to be respected and minority languages, to which Ladin belongs, to be appropriately protected and promoted. Starting in the 1990s, the Italian parliament and provincial assembly have passed laws and regulations protecting the Ladin language and culture. A cultural institute was founded to safeguard and educate in the language and culture. School curricula were adapted in order to teach in Ladin, and street signs are being changed to bilingual.[20]

Ladin is also recognized as a protected language in the Province of Belluno in Veneto region pursuant to the Standards for Protection of Historic Language Minorities Act No. 482 (1999). In comparison with South Tyrol and Trentino, the wishes of the Ladins have barely been addressed by the regional government. In a popular referendum in October 2007, the inhabitants of Cortina d'Ampezzo overwhelmingly voted to leave Veneto and return to South Tyrol.[21][22] The redrawing of the provincial borders would return Cortina d'Ampezzo, Livinallongo del Col di Lana and Colle Santa Lucia to South Tyrol, to which they traditionally belonged when part of the County of Tyrol or the Bishopric of Brixen.

Although the Ladin communities are spread out over three neighbouring regions, the Union Generala di Ladins dles Dolomites is asking that they be reunited.[23] The Ladin Autonomist Union and the Fassa Association run on a Ladin list and have sought more rights and autonomy for Ladin speakers. Ladins are also guaranteed political representations in the assemblies of Trentino and South Tyrol due to a reserved seats system.

In South Tyrol, in order to reach a fair allocation of jobs in public service, a system called "ethnic proportion" was established in the 1970s. Every ten years, when the general census of population takes place, each citizen has to identify with a linguistic group. The results determine how many potential positions in public service are allocated for each linguistic group. This has theoretically enabled Ladins to receive guaranteed representation in the South Tyrolean civil service according to their numbers.

The recognition of minority languages in Italy has been criticised since the implementation of Act No. 482 (1999), especially due to alleged financial benefits. This applies also to Ladin language, especially in the province of Belluno.[24]

Subdivisions

A possible subdivision of Ladin language[25] identifies six major groups.

Athesian Group of the Sella

The dialects of the Athesian group (from the river Adige Basin) of the Sella are spoken in South Tyrol:

- Gherdëina, spoken in Val Gardena by 8,148 inhabitants (80–90 % of the population);

- Badiot and Maró, spoken in Val Badia and in Mareo by 9,229 people, i.e. 95% as native language.

The South Tyrolean dialects are the ones which preserverd the original Ladin characteristics better than all others.

|

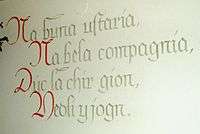

Sample of Ladin language from Gherdëina

Adele Moroder-Lenert talks about her grandparents. (From the Archive Radio Ladin – Alex Moroder) |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

|

Sample of Ladin language from Gherdëina

Tresl Gruber talks about her youth. (Aired on Radio Ladin in 1961)[26] |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Trentinian Group of the Sella

The names of the Ladin dialects spoken in the Fassa Valley in Trentino are Moenat, Brach, and Cazet. 82,8% of the inhabitants of Fassa Valley are natively Ladin speaking;[27] the Ladin language in Fassa is influenced by Trentinian dialects.

Agordino Group of the Sella

In the Province of Belluno the following dialects are considered as part of the Agordino group:

- Fodom, also called Livinallese, spoken in Livinallongo del Col di Lana and Colle Santa Lucia, native language of 80–90% of the people;

- Rocchesano in the area of Rocca Pietore. While Laste di Sopra (Ladin Laste de Sora) and Sottoguda (Ladin Stagùda) are predominantely Ladin, in Alleghe, San Tomaso, Falcade so called Ladin-Venetian dialects are spoken, with strong Venetian influx;

- Ladin in the area of Agordo and Valle del Biois, even if some regard it rather as Venetian-Ladin.

Ampezzan Group

Spoken in Cortina d'Ampezzo (Anpezo), similar to Cadorino dialect.

Even in Valle di Zoldo (from Forno-Fôr upwards) there are elements of the Ampezzan Group.

Cadorino Group

Spoken in Cadore and Comelico and best known as Cadorino dialect.[28]

Nones and Solandro Group

In Western Trentino, in Non Valley, Val di Sole, Val di Peio, Val di Rabbi and part of Val Rendena, detached from the dolomitic area, dialects are spoken that are often considered as Ladin language (Anaunic Ladin), but enjoy strong influences from Trentinian an Eastern Lombard dialects.

Sample texts

Lord's Prayer

The first part of the 'Lord's Prayer' in Standard Ladin, Latin and Italian for comparison:

| Ladin | Latin | Italian | Spanish | Portuguese | French | Romanian | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pere nost, che t'ies en ciel, |

Pater noster, qui es in caelis: |

Padre nostro che sei nei cieli, |

Padre nuestro que estás en los cielos, |

Pai nosso, que estais no céu, |

Notre Père, qui es aux cieux, |

Tatăl nostru, care eşti în ceruri, |

Our Father, who art in heaven, |

Common phrases

| English | Italian | Gherdëina | Fassa Valley | Zoldo | Alleghe | Nones | Solandro |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What's your name? | Come ti chiami? | Co es'a inuem? | Co èste pa inom? | Ke asto gnóm? | kome te ciameto? | Come te clames po? (Che gias nom po?) |

Che jas nòm po? |

| How old are you? | Quanti anni hai? | Tan d'ani es'a? | Cotenc egn èste pa? | Quainch agn asto? | Kotanc agn asto? | Canti ani gias po? | Cuanti àni gh'às/jas po? |

| I go home. | Vado a casa. | Vede a cësa. | Vae a cèsa. | Vade a casa. | Vade a ciesa. | Von a ciasa. | Von a chjasô / casa. |

| I live in Trent. | Vivo a Trento. | Stei a Trent. | Stae ja Trent. | Staghe a Trento. | Stae a Trient. | Ston a Trent | Ston a Trent |

| Where do you live? | Dove abiti? | Ulà stessa? | Olà stèste pa? | An do stasto? | Ulà stasto? | En do abites? | Ndo abites po? |

Numbers in Ladin

- Badiot

|

|

|

|

- Fashan

|

|

|

|

- Gherdëina

|

|

|

|

- Fodom and Rocchesàn

|

Phonology

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tʃ | |||

| voiced | dʒ | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | h | |

| voiced | v | z | ʒ | |||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Approximant | l | |||||

- /m, p, b/ are bilabial, whereas /f, v/ are labiodental.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Close mid | e | o | |

| Open mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | a |

The [ɜ] vowel, spelled ⟨ë⟩, as in Urtijëi (![]() pronunciation ), occurs in some local dialects but is not a part of Standard Ladin.

pronunciation ), occurs in some local dialects but is not a part of Standard Ladin.

See also

References

- ↑ Ladin at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Ladin". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Collins English Dictionary (Online)". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ "Merriam-Webster Dictionary (Online)". Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ↑ Giovan Battista Pellegrini: Ladinisch: Interne Sprachgeschichte II. Lexik. In: Lexikon der Romanistischen Linguistik, III. Tübingen, Niemeyer 1989, ISBN 3-484-50250-9, p. 667: È necessaria innanzi tutto una precisazione geografica circa l'estensione del gruppo linguistico denominato «ladino centrale», dato che le interpretazioni possono essere varie.

- ↑ Johannes Kramer: Ladinisch: Grammatikographie und Lexikographie. In: Lexikon der Romanistischen Linguistik, III. Tübingen, Niemeyer 1989, ISBN 3-484-50250-9, p. 757: Im folgenden sollen die Grammatiken und Wörterbücher im Zentrum stehen, die das Dolomitenladinische im engeren Sinne ([...] Gadertalisch [...], Grödnerisch, Buchensteinisch, Fassanisch [...]) behandeln, während Arbeiten zum Cadorinischen [...] und zum Nonsbergischen [...] summarisch behandelt werden.

- ↑ The office for Ladin language planning

- ↑ SECOND REPORT SUBMITTED BY ITALY PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 2 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES (received on 14 May 2004), APPROPRIATELY IDENTIFIED TERRITORIAL AREAS Decisions adopted by provincial councils, European Council; the Municipality of Calalzo di Cadore was recognized following the decision adopted by the provincial council of Belluno on 25 June 2003.

- ↑ "South Tyrol in Figures" (PDF). Declaration of language group affiliation – Population Census 2011. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- ↑ The subdivisions Bula, Roncadic and Sureghes have a majority of ladin speakers

- ↑ Census data 2011

- ↑ "15° Censimento della popolazione e delle abitazioni. Rilevazione sulla consistenza e la dislocazione territoriale degli appartenenti alle popolazioni di lingua ladina, mòchena e cimbra (dati provvisori)" (PDF). A (in Italian). Autonomous Province of Trento. 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- ↑ "Ladini: i nonesi superano i fassani". Trentino Corriere Alpi. 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ↑ "La pruma valutazions del diretor de l'Istitut Cultural Ladin Fabio Ciocchetti". La Usc di Ladins, nr. 26 /06 de messel 2012, p. 25. 2012.

- ↑ Italian Ministry of Education, contributions among others by Prof. Gabriele Jannaccaro, Univ. Milano-Bicocca, La ladinità bellunese è piuttosto etnica che linguistica, e le varietà parlate dei comuni ladini sono dei dialetti veneti alpini grammaticalmente non diversi da quelli dei comuni che non si sono dichiarati ladini (Ladinity in the province of Belluno is more ethnic than linguistic, and the varieties spoken by Ladin municipalities are Venetian alpine dialects grammatically identical to those spoken in the municipalities that did not declare themselves as Ladin)

- ↑ Paul Videsott, Chiara Marcocci, Bibliografia retoromanza 1729–2010

- ↑ Map showing similarity of dialects around Belluno, from "Dialectometric Analysis of the Linguistic Atlas of Dolomitic Ladin and Neighbouring Dialects (ALD-I & ALD-II)" by Prof. Dr. Roland Bauer, 2012, University of Salzburg

- ↑ |First Ladin-Gherdëina

- ↑ "Die Ladiner betrachten sich seit jeher als eigenständige Ethnie" and "Wir sind keine Italiener, wollen von jeher nicht zu ihnen gezählt werden und wollen auch in Zukunft keine Italiener sein! (..) Tiroler sind wir und Tiroler wollen wir bleiben!" (The ladins view themselves as a distinct ethnic group: ... we are not Italians and since ever do not want to be considered as part of them! We are Tyroleans and we want to stay Tyroleans!) from Die questione ladina – Über die sprachliche und gesellschaftliche Situation der Dolomitenladiner by Martin Klüners, ISBN 9 783638 159159

- ↑ "Canazei – Skiferie i Canazei i Italien" (in Danish). Canazei.dk. 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- ↑ "Cresce la Voglia di Trentino Alto Adige Quorum Raggiunto a Cortina d'Ampezzo". La Repubblica (in Italian). 28 October 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ↑ "Cortina Vuole Andare in Alto Adige". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 29 October 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ↑ Homepage of the Union Generala di Ladins dles Dolomites

- ↑ Fiorenzo Toso, Univ. di Sassari: I benefici (soprattutto di natura economica) previsti dalla legge482/1999 hanno indotto decine di amministrazioni comunali a dichiarare una inesistente appartenenza a questa o a quella minoranza: col risultato, ad esempio, che le comunità di lingua ladina si sono moltiplicate nel Veneto (financial benefits provided by the law 482/1999 led dozens of municipalities to declare a non-existent affiliation to some minority, resulting e.g. in a multiplication of the Ladin-speaking communities in the Veneto region)

- ↑ Mário Eduardo Viaro, O reto-românico: unidade e fragmentação. Caligrama. Belo Horizonte, 14: 101–156, December 2009.

- ↑ File from Archiv Radio Ladin – Alex Moroder Mediathek Bozen Signatur CRLG_216_Spur2

- ↑ Tav. I.5 appartenenza alla popolazione di lingua ladina (censimento 2001), Annuario statistico della provincia autonoma di Trento 2006 – Tav. I.5

- ↑ Giovan Battista Pellegrini, I dialetti ladino-cadorini, Miscellanea di studi alla memoria di Carlo Battisti, Firenze, Istituto di studi per l'Alto Adige, 1979

- 1 2 Gramatica dl Ladin Standard, Servisc de Planificazion y Elaborazion dl Lingaz Ladin, 2001, ISBN 88-8171-029-3

Further reading

- Rut Bernardi, Curs de gherdëina – Trëdesc lezions per mparé la rujeneda de Gherdëina/Dreizehn Lektionen zur Erlernung der grödnerischen Sprache. St. Martin in Thurn: Istitut Ladin Micurà de Rü, 1999, ISBN 88-8171-012-9

- Vittorio Dell'Aquila und Gabriele Iannàccaro, Survey Ladins: Usi linguistici nelle Valli Ladine. Trient: Autonome Region Trentino-Südtirol, 2006, ISBN 88-86053-69-X

- Marco Forni: Wörterbuch Deutsch–Grödner-Ladinisch. Vocabuler tudësch–ladin de Gherdëina. Istitut Ladin Micurà de Rü, St. Martin in Thurn 2002, ISBN 88-8171-033-1

- Günter Holtus, Michael Metzeltin, Christian Schmitt, eds., Lexikon der Romanistischen Linguistik (LRL), 12 vols. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1988–2005; vol. 3: Die einzelnen romanischen Sprachen und Sprachgebiete von der Renaissance bis zur Gegenwart. Rumänisch, Dalmatisch / Istroromanisch, Friaulisch, Ladinisch, Bündnerromanisch, 1989.

- Theodor Gartner, Ladinische Wörter aus den Dolomitentälern. Halle: Niemeyer, 1913 (Online version)

- Maria Giacin Chiades, ed., Lingua e cultura ladina. Treviso: Canova, 2004, ISBN 88-8409-123-3 ()

- Constanze Kindel, “Ladinisch für Anfänger”, Die Zeit 4 (2006) (Online version)

- Heinrich Schmid, Wegleitung für den Aufbau einer gemeinsamen Schriftsprache der Dolomitenladiner. St. Martin in Thurn: Istitut Cultural Ladin Micurà de Rü & San Giovanni: Istitut Cultural Ladin Majon di Fascegn, 1994 (Online version)

- Servisc de Planificazion y Elaborazion dl Lingaz Ladin (SPELL), Gramatica dl Ladin Standard. St. Martin in Thurn, Istitut Cultural Ladin Micurà de Rü, 2001, ISBN 88-8171-029-3 (http://www.spell-termles.ladinia.net/documents/gramatica_LS_2001.pdf Online version)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ladin language. |

| Ladin language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| For a list of words relating to Ladin, see the Ladin language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The office for Ladin language planning

- Rai Ladinia – Newscasts and broadcasts from public broadcaster Rai Sender Bozen.

- Noeles.info – News portal in Ladin.

- Weekly Paper – La Usc Di Ladins (The Voice of the Ladins, in Ladin).

- Ladinienatlas ALD-I

- Linguistic Atlas of Dolomitic Ladinian and neighbouring Dialects – Speaking Linguistic Atlas

- Grzega, Joachim, (in German) Ku-eichstaett.de, Materialien zu einem etymologischen Wörterbuch des Dolomitenladinischen (MEWD), Katholische Universität Eichstätt-Ingolstadt (KU) 2005.

- Italian-Fassano Ladin Dictionary

- Italian-Cadorino Ladin Dictionary

- Italian-Cadorino Ladin Dictionary

- Italian-Gardenese Ladin Dictionary

- Italian-Badiotto Ladin Dictionary

- German-Gardenese Ladin Dictionary

- German-Badiotto Ladin Dictionary

- Ladin basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Declaration of language group affiliation in South Tyrol – Population Census 2001