Hypoxia (environmental)

Hypoxia refers to low oxygen conditions. Normally, 20.9% of the gas in the atmosphere is oxygen. The partial pressure of oxygen in the atmosphere is 20.9% of the total barometric pressure.[1] In water however, oxygen levels are much lower, approximately 1%, and fluctuate locally depending on the presence of photosynthetic organisms and relative distance to the surface (if there is more oxygen in the air, it will diffuse across the partial pressure gradient).[2]

Atmospheric hypoxia

Atmospheric hypoxia occurs naturally at high altitudes. Total atmospheric pressure decreases as altitude increases, causing a lower partial pressure of oxygen which is defined as hypobaric hypoxia. Oxygen remains at 20.9% of the total gas mixture, differing from hypoxic hypoxia, where the percentage of oxygen in the air (or blood) is decreased. This is common, for example, in the sealed burrows of some subterranean animals, such as blesmols.[3] Atmospheric hypoxia is also the basis of altitude training which is a standard part of training for elite athletes. Several companies mimic hypoxia using normobaric artificial atmosphere.

Aquatic hypoxia

Oxygen depletion is a phenomenon that occurs in aquatic environments as dissolved oxygen (DO; molecular oxygen dissolved in the water) becomes reduced in concentration to a point where it becomes detrimental to aquatic organisms living in the system. Dissolved oxygen is typically expressed as a percentage of the oxygen that would dissolve in the water at the prevailing temperature and salinity (both of which affect the solubility of oxygen in water; see oxygen saturation and underwater). An aquatic system lacking dissolved oxygen (0% saturation) is termed anaerobic, reducing, or anoxic; a system with low concentration—in the range between 1 and 30% saturation—is called hypoxic or dysoxic. Most fish cannot live below 30% saturation. A "healthy" aquatic environment should seldom experience less than 80%. The exaerobic zone is found at the boundary of anoxic and hypoxic zones.

Hypoxia can occur throughout the water column and also at high altitudes as well as near sediments on the bottom. It usually extends throughout 20-50% of the water column, but depending on the water depth and location of pycnoclines (rapid changes in water density with depth). It can occur in 10-80% of the water column. For example, in a 10-meter water column, it can reach up to 2 meters below the surface. In a 20-meter water column, it can extend up to 8 meters below the surface.[4]

Causes of hypoxia

Oxygen depletion can result from a number of natural factors, but is most often a concern as a consequence of pollution and eutrophication in which plant nutrients enter a river, lake, or ocean, and phytoplankton blooms are encouraged. While phytoplankton, through photosynthesis, will raise DO saturation during daylight hours, the dense population of a bloom reduces DO saturation during the night by respiration. When phytoplankton cells die, they sink towards the bottom and are decomposed by bacteria, a process that further reduces DO in the water column. If oxygen depletion progresses to hypoxia, fish kills can occur and invertebrates like worms and clams on the bottom may be killed as well.

Hypoxia may also occur in the absence of pollutants. In estuaries, for example, because freshwater flowing from a river into the sea is less dense than salt water, stratification in the water column can result. Vertical mixing between the water bodies is therefore reduced, restricting the supply of oxygen from the surface waters to the more saline bottom waters. The oxygen concentration in the bottom layer may then become low enough for hypoxia to occur. Areas particularly prone to this include shallow waters of semi-enclosed water bodies such as the Waddenzee or the Gulf of Mexico, where land run-off is substantial. In these areas a so-called "dead zone" can be created. Low dissolved oxygen conditions are often seasonal, as is the case in Hood Canal and areas of Puget Sound, in Washington State.[5] The World Resources Institute has identified 375 hypoxic coastal zones around the world, concentrated in coastal areas in Western Europe, the Eastern and Southern coasts of the US, and East Asia, particularly in Japan.[6]

Hypoxia may also be the explanation for periodic phenomena such as the Mobile Bay jubilee, where aquatic life suddenly rushes to the shallows, perhaps trying to escape oxygen-depleted water. Recent widespread shellfish kills near the coasts of Oregon and Washington are also blamed on cyclic dead zone ecology.[7]

Solutions

To combat hypoxia, it is essential to reduce the amount of land-derived nutrients reaching rivers in runoff. This can be done by improving sewage treatment and by reducing the amount of fertilizers leaching into the rivers. Alternately, this can be done by restoring natural environments along a river; marshes are particularly effective in reducing the amount of phosphorus and nitrogen (nutrients) in water. Other natural habitat-based solutions include restoration of shellfish populations, such as oysters. Oyster reefs remove nitrogen from the water column and filter out suspended solids, subsequently reducing the likelihood or extent of harmful algal blooms or anoxic conditions.[8] Foundational work toward the idea of improving marine water quality through shellfish cultivation was conducted by Odd Lindahl et al., using mussels in Sweden.[9]

Technological solutions are also possible, such as that used in the redeveloped Salford Docks area of the Manchester Ship Canal in England, where years of runoff from sewers and roads had accumulated in the slow running waters. In 2001 a compressed air injection system was introduced, which raised the oxygen levels in the water by up to 300%. The resulting improvement in water quality led to an increase in the number of invertebrate species, such as freshwater shrimp, to more than 30. Spawning and growth rates of fish species such as roach and perch also increased to such an extent that they are now amongst the highest in England.[10]

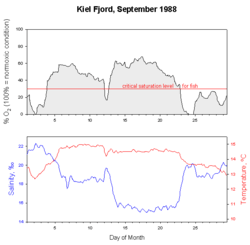

In a very short time the oxygen saturation can drop to zero when offshore blowing winds drive surface water out and anoxic depth water rises up. At the same time a decline in temperature and a rise in salinity is observed (from the longterm ecological observatory in the seas at Kiel Fjord, Germany). New approaches of long-term monitoring of oxygen regime in the ocean observe online the behavior of fish and zooplankton, which changes drastically under reduced oxygen saturations (ecoSCOPE) and already at very low levels of water pollution.

See also

- Algal blooms

- Anoxic event

- Dead zone (ecology)

- Denitrification

- Eutrophication

- Hypoxia in fish

- Ocean deoxygenation

- Oxygen minimum zone

References

- ↑ Brandon, John. "The Atmosphere, Pressure and Forces". Meteorology. Pilot Friend. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ↑ "Dissolved Oxygen". Water Quality. Water on the Web. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ↑ Roper, T.J.; et al. (2001). "Environmental conditions in burrows of two species of African mole-rat, Georychus capensis and Cryptomys damarensis". Journal of Zoology. 254 (1): 101–107. doi:10.1017/S0952836901000590.

- ↑ Rabalais, Nancy; Turner, R. Eugene; Justic´, Dubravko; Dortch, Quay; Wiseman, William J. Jr. Characterization of Hypoxia: Topic 1 Report for the Integrated Assessment on Hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico. Ch. 3. NOAA Coastal Ocean Program, Decision Analysis Series No. 15. May 1999. < http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/products/hypox_t1final.pdf>. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Puget Sound: Hypoxia http://www.eopugetsound.org/science-review/section-4-dissolved-oxygen-hypoxia

- ↑ Selman, Mindy (2007) Eutrophication: An Overview of Status, Trends, Policies, and Strategies. World Resources Institute.

- ↑ oregonstate.edu – Dead Zone Causing a Wave of Death Off Oregon Coast (8/9/2006)

- ↑ Kroeger, Timm (2012) Dollars and Sense: Economic Benefits and Impacts from two Oyster Reef Restoration Projects in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. TNC Report.

- ↑ Lindahl, O.; Hart, R.; Hernroth, B.; Kollberg, S.; Loo, L. O.; Olrog, L.; Rehnstam-Holm, A. S.; Svensson, J.; Svensson, S.; Syversen, U. (2005). "Improving marine water quality by mussel farming: A profitable solution for Swedish society". Ambio. 34 (2): 131–138. PMID 15865310. doi:10.1579/0044-7447-34.2.131.

- ↑ Hindle, P.(1998) (2003-08-21). "Exploring Greater Manchester — a fieldwork guide: The fluvioglacial gravel ridges of Salford and flooding on the River Irwell" (pdf). Manchester Geographical Society. Retrieved 2007-12-11. p.13

Sources

- Kils, U., U. Waller, and P. Fischer (1989). "The Fish Kill of the Autumn 1988 in Kiel Bay". International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. C M 1989/L:14.

- Fischer P.; U. Kils (1990). "In situ Investigations on Respiration and Behaviour of Stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus and the Eelpout Zoaraes viviparus During Low Oxygen Stress". International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. C M 1990/F:23.

- Fischer P.; K. Rademacher; U. Kils (1992). "In situ investigations on the respiration and behaviour of the eelpout Zoarces viviparus under short term hypoxia". Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 88: 181–184. doi:10.3354/meps088181.

External links

- Hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico

- Scientific Assessment of Hypoxia in U.S. Coastal Waters Council on Environmental Quality

- Dead zone in front of Atlantic City

- Hypoxia in Oregon Waters