Hypocaust

A hypocaust (Latin hypocaustum) is a system of central heating in a building that produces and circulates hot air below the floor of a room, and may also warm the walls with a series of pipes through which the hot air passes; this air can warm the upper floors as well.[1] The word derives from the Ancient Greek hypo meaning "under" and caust-, meaning "burnt" (as in caustic). The earliest reference to such a system suggests that the temple of Ephesus in 350 BCE was heated in this manner,[2] although Vitruvius attributes its invention to Sergius Orata in c.80 BCE.[3] Its invention improved the hygiene and living conditions of citizens, and was a forerunner of modern central heating.

Roman operation

.jpg)

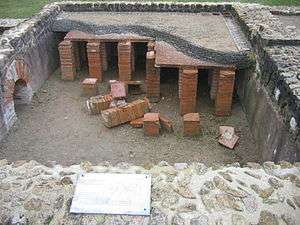

Hypocausts were used for heating hot baths and other public buildings in ancient Rome, but their use in homes was limited to the wealthy due to their high cost.[1] The ruins of Roman hypocausts have been found throughout Europe (for example in Italy, England,[4] Spain,[5] France, Switzerland and Germany[6]) and in Africa[6] as well.

The ceiling of the hypocaust was raised above the ground by pillars, called pilae stacks, supporting a layer of tiles, followed by a layer of concrete, then the floor tiles of the rooms above. Hot air and smoke from the furnace would circulate through this enclosed area and then up through clay or tile flues in the walls of the rooms above to outlets in the roof, thereby heating the floors and walls of the rooms above. Rooms intended to be the warmest were located nearest to the furnace below, the heat output of which was regulated by adjusting the amount of wood fed to the fire. It was expensive and labour-intensive to run a hypocaust, as it required constant attention to the fire and a lot of fuel, so it was a feature usually encountered only in large villas and public baths.

Vitruvius describes their construction and operation in his work De architectura in about 15 BCE, including details about how fuel could be conserved by building the hot room (caldarium) for men next to that for women, with both adjacent to the tepidarium, so as to run the public baths efficiently. He also describes a device for adjusting the heat by a bronze ventilator in the domed ceiling.

Remains of many Roman hypocausts have survived throughout Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa.

Non-Roman analogues

Excavations at Mohenjo-daro in what is now Pakistan have unearthed what is believed to be a hypocaust lined with bitumen-coated bricks. If it fulfilled a similar role, the structure would pre-date the earliest Roman hypocaust by as much as 2000 years.

In 1984–1985, in the Republic of Georgia, excavations in the ancient settlement of Dzalisi uncovered a large castle complex, featuring a well-preserved hypocaust built between 200–400 BCE.

Dating back to 1000 BCE,[7] Korean houses have traditionally used ondol to provide floor heating on similar principles as the hypocaust, drawing smoke from a wood fire typically used for cooking. Ondol heating was common in Korean homes until the 1960s, by which time dedicated ondol installations were typically used to warm the main room of the house, burning a variety of fuels such as coal and biomass.

On a smaller scale, in Northern China the Kang bed-stove has a long history.[8][9]

After the Romans

With the decline of the Roman Empire, the hypocaust fell into disuse, especially in the western provinces. In Britain, from c.400 until c.1900, central heating did not exist, and hot baths were rare.[10] In the Iberian Peninsula, the Roman system was adopted for the heating of Hispano-Islamic (Al Andalus) baths (hammams).[11] A derivation of hypocaust, the gloria, was in use in Castile until the arrival of modern heating. After the fuel (mainly wood) was reduced to ashes, the air intake was closed to keep hot air inside and to slow combustion.

See also

- De Architectura

- Roman engineering

- Roman technology

- Ondol

- Gloria (Spanish heating system)

- Masonry heater (similar to Kachelofen in the German Wikipedia).

- Kang bed-stove

- Vitruvius

- Underfloor heating

References

- 1 2 Tomlinson, Charles (1850-01-01). A rudimentary treatise on warming and ventilation: being a concise exposition of the general principles of the art of warming and ventilating domestic and public buildings, mines, lighthouses, ships, etc. J. Weale. p. 53.

- ↑ Mitchell, Patrick (2008-03-01). Central Heating, Installation, Maintenance and Repair. WritersPrintShop. p. 3. ISBN 9781904623625.

- ↑ Forbes (1966-01-01). Studies in Ancient Technology. BRILL. pp. 54–55. ISBN 9004006265.

- ↑ "hypocaust | architecture". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-01-13.

- ↑ Carr, Karen Eva (2002-01-01). Vandals to Visigoths: Rural Settlement Patterns in Early Medieval Spain. University of Michigan Press. p. 185. ISBN 0472108913.

- 1 2 Forbes, Robert James (1965-01-01). Studies in Ancient Technology. Brill Archive. pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Bean, Robert; Olesen, Bjarne W.; Kim, Kwang Woo (2010). "History of Radiant Heating & Cooling Systems". ASHRAE. 52 – via Gale: Educators Reference Complete.

- ↑ http://www.healthyheating.com/History_of_Radiant_Heating_and_Cooling/History_of_Radiant_Heating_and_Cooling_Part_1.pdf

- ↑ Zhuang, Zhi; Li, Yuguo; Chen, Bin; Jiye; Guo (2009), "Chinese kang as a domestic heating system in rural northern China—A review", Energy and Buildings, 41 (1): 111–119, doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2008.07.013

- ↑ Winston Churchill (1956), A History of the English Speaking Peoples: The Birth of Britain, Dodd, Mead & Company, p. 35

- ↑ Dodds, Jerrilynn Denise; N.Y.), Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York; Alhambra, Patronato de la (1992-01-01). Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 141. ISBN 9780870996368.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hypocausts. |

- About Roman baths (referring to Sergius Orata), by William Smith.

- Disputing the priority of Sergius Orata Garrett G. Fagan's paper "Sergius Orata: Inventor of the Hypocaust?" published in Phoenix, Vol. 50, No. 1 (Spring, 1996), pp. 56–66

- Hypocaust