Hyperdiffusionism in archaeology

Hyperdiffusionism is a hypothesis stating that one civilization or people is the creator of all logical and great things, which are then diffused to less civilized nations. Thus, all great civilizations that share similar cultural practices, such as construction of pyramids, are derived from the same single ancient nation.[1] According to its proponents, examples of hyperdiffusionism can be found in religious practices, cultural technologies, megalithic monuments, and lost ancient civilizations.

Hyperdiffusionism is different in a few ways from trans-cultural diffusion, one being that hyperdiffusionism is usually not testable due its pseudo-scientific nature (Williams 1991, 255-156). Additionally, unlike trans-cultural diffusion, hyperdiffusionism does not use trading and cultural networks to explain the expansion of a society within a single culture; instead, hyperdiffusionists claim that all major cultural innovations and societies derive from one (usually lost) ancient civilization (Williams 1991, 224-232). Ergo, the Tucson artifacts derive from Ancient Rome, carried by the "Romans who came across the Atlantic and then overland to Arizona;" this is believed because the artifacts resembled known ancient Roman artifacts (Williams 1991, 246).

Some key proponents

Charles Hapgood

- In Charles Hapgood's book Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings, he concludes that ancient land formations gave way to hyperdiffusionism and the diffusion "of a true culture."[2] This culture could have been more advanced than that of Egypt or Greece because it was the foundation of a worldwide culture. Hapgood also suggests that the Three-age system of archeology is irrelevant due to primitive cultures co-existing with modern societies (Hapgood 1966, pp. 193–194).

Grafton Elliot Smith

- Heliolithic Culture, as Grafton Elliot Smith refers to it, consists of cultural practices such as megaliths. Similar designs and methods of construction of such pieces have what seem like a linear geographical distribution.[3] These heliolithic cultures can refer to religious customs that share distinctive practices, such as the worship of a Solar Deity. As this trope is seen in numerous belief systems, Smith believes it is diffused from one ancient civilization (Smith 1929, p. 132).

- Early Man Distribution refers to Smith's implication that Man derived from "six well-defined types of mankind," who comprise the sources for Earth's population.[4] The six types of mankind are the Aboriginal Australians, Negros, Mongols, and Mediterranean, Alpine, and the Nordic races (Smith 1931, 15). Recently this classification has been labeled as scientific racism.

Barry Fell

- Mystery Hill,[5] or America's Stonehenge, is the site which Barry Fell refers to as the primary basis of his hypothesis that ancient Celts once populated New England. Mystery Hill, Fell believes, was a place of worship for the Celts and Phoenicia mariners (Fell 1976, 91). These ancient mariners, more commonly known as the Druids, are said to have populated Europe at the same time. He hypothesizes that they were the ancient settlers of North America. Also, he believes that what he describes as inscriptions on stone and tablet artifacts from this site are in an ancient language derived from common sources of the Goidelic languages (Fell 1976, 92).

These three authors describe hyperdiffusionism as the driving force behind the apparent cultural similarities and population distribution among all civilizations. Hapgood's hypothesis states that one specific civilization is responsible for similar cultural practices in all other civilizations. Smith says that religions are proof of hyperdiffusionism, as similar worship ceremonies and symbols recur in geographically separated societies. Also, Smith believes that the Earth's population is made up of six types of humans, who diffused across the Earth's continents by virtue of their skin color (Smith 1931, 47-48). Finally, Fell asserts that ancient mariners, such as Druids and Phoenicians, traveled from Europe and comprised the early population of ancient America.

Carl Whiting Bishop

Carl Whiting Bishop in the 1930s and the 1940s produced a series of articles arguing hyperdiffusionism in explaining the expansion of technology into China. Among the scholars influenced by Bishop were Owen Lattimore, who was intrigued by Bishop's emphasis on geography as a shaping factor in Chinese civilization and his emphasis on field work rather than library research.[6]

Popular culture

Atlantis and Lemuria

Lost civilizations of the sea

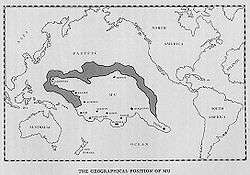

- These are two ancient civilizations that hyperdiffusionists hypothesized to be sources for the diffusion of similar cultural practices between societies on opposite sides of the oceans. Just as the people of Atlantis populated Egypt, according to G. Elliot Smith, Egypt was the source of civilization for Asia, India, China, the Pacific, and eventually America (Smith 1927, 45).

Book map1

Book map1

Mayans

Culture

- According to Hapgood, the pyramids in South America and Mexico may be indicative of cultural practices shared with ancient Egyptian civilization (Hapgood 1966, pp. 200). He theorized that the ancient Maya were strongly influenced by the diffusion of ancient Egyptian social and political cultures,[7] and that they became a civilized culture due to the migration of citizens from Atlantis after that island sank.[8] It is also said the Mayans have a classical culture trait found in their materialistic artifacts that resemble what could possibly be related to that of Greece (Fagan 2006, 147). This plays into Plato's Account for the ancient battle for Atlantis, which led to the downfall of the civilization.

Religion and mythology

Egypt

- Hapgood finds evidence of ancient Egyptian "expression" in writings of Hinduism and Buddhism. He notes that writings, there are also similar deities that are worshiped throughout the world. Furthermore, there are myths and creation stories that are said to have a common origin in Egypt (Hapgood 1966, 204-205).

- Mummification, as believed by G. Elliot Smith, is a prime example of how religious customs prove the diffusion of cultures (Smith 1929, 21). He believes that only an advanced civilization, such as Egypt, could create such a peculiar belief that then spread by way of ancient mariners (Smith 1929, 133-134).

Critiques

Ethnocentrism and racism

Pigeonholes and continuums[9]

- Michael Shermer states that using racial taxonomy in order to make abstract observations of racial superiority is another expression of ethnocentrism (Shermer 2002, 248). He asks, "how can we 'pigeonhole' blacks as permissive or whites as intelligent when such categories...are actually best described as a continuum?" (Shermer 2002, 250). Shermer claims that the belief that one race and/or culture is superior to another defeats the purpose of cultural evolution, and that we cannot dismiss evidence of blending inheritance among all cultures (Shermer 2002, 247-251). Shermer uses The Bell Curve by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray as an example of pigeonholing; Herrnstein and Murray tried to pigeonhole civilization into racial categories based on flawed measures of intelligence (Shermer 2002, 242-244).

Pseudoarchaeology

Fantastic archaeology

- Critical thinker and archaeologist Stephen Williams uses the phrase "Fantastic Archaeology" to describe the archeological theories and discoveries which he defines as "fanciful archaeological interpretations" (Williams 1991, 12). These interpretations usually lack artifacts, data, and testable theories to back up the claims made. True believers in the theory of hyperdiffusionism base their claims of cultural relativism on derivations from ancient cultures. For instance, Hapgood says, "How did the Mayans achieve such precise results...the knowledge may have, of course, been derived by the Babylonians or the Egyptians" (Hapgood 1966, 198).

Hyperdiffusionism versus Independent Invention[10]

Ideology

- Alice Beck Kehoe says that diffusionism is a "grossly racist ideology" (Kehoe 2008, 144). Although she agrees that diffusion of culture can occur through contact and trading, she disagrees with the theory that all civilization came from one superior ancient society (Kehoe 2008, 148). Kehoe explores the "independent invention" of works and techniques using the example of boats. Ancient peoples could have used their boat technology to make contact with new civilizations and exchange ideas. Moreover, the use of boats is a testable theory, which can be evaluated by recreating voyages in certain kinds of vessels, unlike hyperdiffusionism, (Kehoe 2008, 158). Kehoe concludes with the theory of transoceanic contact and makes clear that her argument is not claiming an ancient theory for how cultures diffused and blended, but an argument against the possibility that hyperdiffusionism took place due to alternative testable theories, such as independent inventions and boats (Kehoe 2008, 169).

Culture

The Diffusion Controversy

- Alexander Goldenweiser in Culture: The Diffusion Controversy[11] stated that there are reasons for believing that culture is independent to other cultures that occur simultaneously. In addition, Goldenweiser insists that behavior is primitive and that similar cultures occur together due to the adaptive traits needed to survive. Goldenweiser disagrees with the theory of hyperdiffusionism stating "culture is not contagious" (Goldenweiser 1927, 104) and the data for the theory fails to support it (Goldenweiser 1927. 100-106).

Methods

- Stephen Williams in his chapter "Across The Sea They Came"[12] introduced a few hyperdiffusionists, their discoveries, and how they "tested" artifacts, beginning with Harold S. Gladwin who made his fantastic discoveries at an Arizona Pueblo site, Gila Pueblo Archaeological Foundation. Gladwin favored the diffusion theories which later influenced his methodologies for dating the artifacts at the site. Consequently, this caused him to legitimately ignore the data that was found at the Folsom Site in his chronology as it made his "Man descended from Asia into the New World" theory impossible (Williams 1991, 230).

- The section continues with Cyclone Covey and Thomas W. Bent, specifically their publications on the Tucson Artifacts and Romans traveling to Arizona via hyperdiffusionism theory. Williams pokes fun at this theory in his book Fantastic Archaeology but does state that Covey and Bent failed at hypothesizing exactly how and why these artifacts were found in Arizona; rather, they focused their attention on the artifacts themselves and what makes them like true Roman artifacts (Williams 1991, 240). This gives way to Michael Shermer's fallacy Theory Influences Observation in his book Why People Believe Weird Things and how "theory in part constructs the reality and the reality exists independent of the observer" (Shermer 2002, 46).

- Concluding, Williams points out in the chapter how hyperdiffusionists fail to recognize solid archaeological research methods and/or ignore conflicting data and contextual evidence. They are "tailoring their finds with any similar chronology or in-depth linguistic analysis that fits into their scenarios" (Williams 1991, 255-256).

See also

Notes

- ↑ Fagan, Garrett G., ed. (2006). Archaeological Fantasies. Oxford, England: Routledge. pp. 362–367. ISBN 978-0-415-30593-8.

- ↑ Hapgood, Charles H. (1966). Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings. Philadelphia: Chilton Company. pp. 193–206.

- ↑ Smith, G. Elliot (1929). The Migrations of Early Culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 4–30–132. OCLC 1868131.

- ↑ Smith, G. Elliot (1931). The Evolution of Man. London: Ernest Benn Limited. pp. 13–47. OCLC 637203360.

- ↑ Fell, Barry (1976). Ancient Settlers in the New World. New York: Quadrangle. pp. 81–92. ISBN 0-8129-0624-1.

- ↑ Newman, Robert P. (1992), Owen Lattimore and the 'Loss' of China, University of California Press, p. 24

- ↑ Webster, David (2006), "The Mystique of the Ancient Maya", in Fagan, Garrett G., ed., Archaeological Fantasies, Oxford: Routledge, pp. 129–154, 978-0-415-30593-8

- ↑ Hale, Christopher (2006), "The Atlantean Box", in Fagan, Garrett G., ed., Archaeological Fantasies, Oxford: Routledge, pp. 235–259, ISBN 978-0-415-30593-8

- ↑ Shermer, Michael (2002) [1997]. Why People Believe Weird Things. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-8050-7089-7.

- ↑ Kehoe, Alice Beck (2008). Controversies in Archaeology. California: Left Coast Press, INC. pp. 140–172. ISBN 978-1-59874-062-2.

- ↑ Goldenweiser, Alexander (1927). Culture: The Diffusion Controversy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 99–106. OCLC 1499530.

- ↑ Williams, Stephen (1991). Fantastic Archaeology: The Wild Side of North American Prehistory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 224–257. ISBN 0-8122-1312-2.