Hurricane John (2006)

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

John as a Category 2 hurricane off Jalisco on August 31 | |

| Formed | August 28, 2006 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 4, 2006 |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 130 mph (215 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 948 mbar (hPa); 27.99 inHg |

| Fatalities | 5 direct |

| Damage | $60.9 million (2006 USD) |

| Areas affected | Guerrero, Michoacán, Baja California Sur, Arizona, California, New Mexico, Texas |

| Part of the 2006 Pacific hurricane season | |

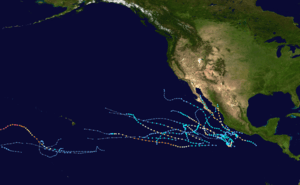

Hurricane John was the eleventh named storm, seventh hurricane, and fifth major hurricane of the 2006 Pacific hurricane season. Hurricane John developed on August 28 from a tropical wave to the south of Mexico. Favorable conditions allowed the storm to intensify quickly, and it attained peak winds of 135 mph (215 km/h) on August 30. Eyewall replacement cycles and land interaction with western Mexico weakened the hurricane, and John made landfall on southeastern Baja California Sur with winds of 110 mph (180 km/h) on September 1. It slowly weakened as it moved northwestward through the Baja California peninsula, and dissipated on September 4. Moisture from the remnants of the storm entered the southwest United States.

The hurricane threatened large portions of the western coastline of Mexico, resulting in the evacuation of tens of thousands of people. In coastal portions of western Mexico, strong winds downed trees, while heavy rain resulted in mudslides. Hurricane John caused moderate damage on the Baja California peninsula, including the destruction of more than 200 houses and thousands of flimsy shacks. The hurricane killed five people in Mexico, and damage totaled $663 million (2006 MXN, $60.8 million 2006 USD). In the southwest United States, moisture from the remnants of John produced heavy rainfall. The rainfall aided drought conditions in portions of northern Texas, although it was detrimental in locations that had received above-normal rainfall throughout the year.

Meteorological history

The tropical wave that would become John moved off the coast of Africa on August 17. It entered the eastern Pacific Ocean on August 24, and quickly showed signs of organization. That night, Dvorak classifications were initiated on the system while it was just west of Costa Rica,[1] and it moved west-northwestward at 10–15 mph (15–25 km/h).[2] Conditions appeared favorable for further development,[3] and convection increased late on August 26 over the area of low pressure.[4] Early on August 27, the system became much better organized about 250 miles (400 km) south-southwest of Guatemala,[5] although convection remained minimal.[6] Early on August 28, banding increased within its organizing convection, and the system developed into Tropical Depression Eleven-E.[7]

Due to low amounts of vertical shear, very warm waters, and abundant moisture, steady intensification was forecast,[7] and the depression strengthened to Tropical Storm John later on August 28.[8] Deep convection continued to develop over the storm,[9] while an eye feature developed within the expanding central dense overcast.[10] The storm continued to intensify, and John attained hurricane status on August 29 while 190 miles (305 km) south-southeast of Acapulco. Banding features continued to increase as the hurricane moved west-northwestward around the southwest periphery of a mid- to upper-level ridge over northern Mexico.[11] The hurricane underwent rapid intensification, and John attained major hurricane status 12 hours after becoming a hurricane.[1] Shortly thereafter, the eye became obscured, and the intensity remained at 115 mph (185 km/h)[12] due to an eyewall replacement cycle. Another eye formed,[13] and based on Reconnaissance data, the hurricane attained Category 4 status on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale on August 30 about 160 miles (260 km) west of Acapulco, or 95 miles (155 km) south of Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán.[14] Hours later, the hurricane underwent another eyewall replacement cycle,[15] and subsequently weakened to Category 3 status as it paralleled the Mexican coastline a short distance offshore.[16]

Due to land interaction and its eyewall replacement cycle, Hurricane John weakened to a 105 mph (170 km/h) hurricane by late on August 31,[1] but restrengthened to a major hurricane shortly after as its eye became better defined.[17] After completing another eyewall replacement cycle, the hurricane again weakened to Category 2 status,[18] and on September 1 it made landfall on Cabo del Este on the southern tip of Baja California Sur with winds of 110 mph (180 km/h).[19] John passed near La Paz as a weakening Category 1 hurricane on September 2,[1] and weakened to a tropical storm shortly thereafter over land.[20] John continued to weaken, and late on September 3 the system deteriorated to a tropical depression while still over land.[21] By September 4, most of the convection decoupled from the circulation towards mainland Mexico, and a clear circulation had not been discernible for 24 hours. Based on the disorganization of the system, the National Hurricane Center issued its last advisory on the system.[22]

Preparations

The Mexican army and emergency services were stationed near the coast, while classes at public schools in and around Acapulco were canceled. Officials in Acapulco advised residents in low-lying areas to be on alert, and also urged fishermen to return to harbor. Authorities in the twin resort cities of Ixtapa and Zihuatanejo closed the port to small ocean craft.[23] Government officials in the state of Jalisco declared a mandatory evacuation for 8,000 citizens in low-lying areas to 900 temporary shelters. Temporary shelters were also set up near Acapulco.[24] The state of Michoacán was on a yellow alert, the middle of a five-level alert system.[25] Carnival Cruise Lines diverted the path of one cruise ship traveling along the Pacific waters off Mexico.[26]

On August 31, the Baja California Sur state government ordered the evacuation of more than 10,000 residents. Those who refused to follow the evacuation order would have been forced to evacuate by the army. Shelters were set up to allow local residents and tourists to ride out the storm.[27] Just weeks after a major flood in the area, officials evacuated hundreds of citizens in Las Presas in northern Mexico area near a dam. All public schools in the area were closed, as well.[28]

The United States' National Weather Service issued flood watches and warnings for portions of Texas and the southern two-thirds of New Mexico.[29]

Impact

Mexico

The powerful winds of Hurricane John produced heavy surf and downed trees near Acapulco. The hurricane produced a 10 foot (3 m) storm surge in Acapulco that flooded coastal roads.[1] In addition, John caused heavy rainfall along the western coast of Mexico, peaking at 12.5 inches (317.5 mm) in Los Planes, Jalisco.[1] The rainfall resulted in mudslides in the Costa Chica region of Guerrero, leaving around 70 communities isolated.[30]

In La Paz, capital of Baja California Sur, the hurricane downed 40 power poles. Authorities cut off the power supply to the city to prevent electrocutions from downed wires. Strong winds downed trees and destroyed many advertisement signs.[31] Heavy rainfall totaling more than 20 inches (500 mm) in isolated areas[29] resulted in ankle-deep flooding, closing many roads in addition to the airport in La Paz.[31] In La Paz, 300 families received damage to their homes, with another 200 families left homeless after their houses were destroyed.[32] The combination of winds and rain destroyed thousands of flimsy houses across the region. The rainfall also destroyed large areas of crops, and also killed many livestock.[33] The rainfall caused the Iguagil dam in Comondú to overflow, isolating 15 towns due to 4 feet (1.5 m) floodwaters.[34] In the coastal city of Mulegé, flash flooding caused widespread damage throughout the town and the death of a United States citizen. More than 250 homes were damaged or destroyed in the town, leaving many people homeless.[32] Severe flooding blocked portions of Federal Highway 1, and damaged an aqueduct in the region.[35]

In all, Hurricane John destroyed hundreds of houses and blew off the roofs of 160 houses on the Baja California peninsula.[36] Five people were killed,[1] and damage in Mexico amounted to $663 million (2006 MXN, $60.8 million 2006 USD).[37]

In Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, across the U.S. border from El Paso, Texas, rainfall from the storm's remnants flooded 20 neighborhoods, downed power lines, and resulted in several traffic accidents.[29] Rainfall from John, combined with continual precipitation during the two weeks before the storm, left thousands of people homeless.[38]

United States

Moisture from the remnants of John combined with an approaching cold front to produce moderate amounts of rainfall across the southwest United States, including a total of 8 inches (200 mm) in Whitharral[39] and more than 3 inches (75 mm) in El Paso, Texas. The rainfall flooded many roads in southwestern Texas,[29] including a ½ mile (800 m) portion of Interstate 10 in El Paso.[40] A slick runway at El Paso International Airport delayed a Continental Airlines jet when its tires were stuck in mud.[29] Rainfall from John in El Paso, combined with an unusually wet year, resulted in twice the normal annual rainfall, and caused 2006 to be the ninth wettest year on record by September.[41] Damage totaled about $100,000 (2006 USD) in the El Paso area from the precipitation.[42] In northern Texas, the rainfall alleviated a severe drought,[28] caused the Double Mountain Fork Brazos River to swell and Lake Alan Henry to overflow.[43] The Texas Department of Transportation closed numerous roads due to flooding from the precipitation, including a portion of U.S. Route 385 near Levelland. Several other roads were washed out.[39]

Moisture derived from John also produced rainfall across southern New Mexico, peaking at 5.25 inches (133 mm) at Ruidoso. The rainfall overflowed rivers, forcing people to evacuate along the Rio Ruidoso.[44] The rainfall also caused isolated road flooding.[29] Rainfall in New Mexico canceled an annual wine festival in Las Cruces and caused muddy conditions at the All American Futurity at the Ruidoso Downs, the biggest day of horse racing in New Mexico.[45] Flooding was severe in Mesquite, Hatch, and Rincon, where many homes experienced 4 feet (1.5 m) of flooding and mud.[46] Some homeowners lost all they owned.[47] Tropical moisture from the storm also produced rainfall in Arizona[29] and Southern California. In California, the rainfall produced eight separate mudslides, trapping 19 vehicles, but caused no injuries.[48]

Aftermath

Branches of the Mexican Red Cross in Guerrero, Oaxaca and Michoacán were put on alert. The organization's national emergency response team was on stand-by to assist the most affected areas.[30] Navy helicopters delivered food and water to remote areas of the Baja California peninsula.[33] The Mexican Red Cross dispatched 2,000 food parcels to the southern tip of Baja California Sur.[49] In the city of Mulegé, gas supply, which was necessary to run generators, was low, drinking water was gone, and the airstrip was covered with mud. Many homeless residents initially stayed with friends or in government-run shelters.[32] Throughout the Baja California peninsula, thousands remained without water or electricity two days after the storm,[35] although a pilot from Phoenix prepared to fly to the disaster area with 100 gallons (380 litres) of water. Other pilots were expected to execute similar flights, as well.[32] The office of Baja California Sur Tourism stated that minimal damage occurred to the tourism infrastructure, with only minimal delays to airports, roads, and maritime facilities.[50] The Episcopal Relief and Development delivered food, clothing, medicine, and transportation to about 100 families, and gave mattresses to about 80 families.[38]

Many residents in Tucson, including more than 50 students, delivered supplies to flood victims in New Mexico, including clothing and other donations.[47]

See also

- List of Category 4 Pacific hurricanes

- List of Arizona hurricanes

- List of Baja California hurricanes

- Timeline of the 2006 Pacific hurricane season

- Other tropical cyclones of the same name

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Richard J. Pasch (2006). "Hurricane John Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2006-11-15.

- ↑ Roberts/Beven (2006). "August 26 Tropical Weather Outlook". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Mainelli/Knabb (2006). "August 26 Tropical Weather Outlook (2)". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Blake/Stewart (2006). "August 26 Tropical Weather Outlook (3)". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Roberts/Pasch (2006). "August 27 Tropical Weather Outlook". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Blake/Rhome/Franklin (2006). "August 27 Tropical Weather Outlook (2)". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- 1 2 Pasch/Landsea (2006). "Tropical Depression Eleven-E Discussion One". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Pasch/Landsea (2006). "Tropical Storm John Discussion Two". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Rhome/Franklin (2006). "Tropical Storm John Discussion Three". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Brown/Stewart (2006). "Tropical Storm John Discussion Four". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Mainelli/Pasch (2006). "Hurricane John Discussion Five". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Rhome/Franklin (2006). "Hurricane John Discussion Seven". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Brown/Stewart (2006). "Hurricane John Discussion Eight". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Mainelli/Franklin (2006). "Hurricane John Discussion Nine". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Mainelli/Pasch (2006). "Hurricane John Discussion Ten". Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Rhome/Beven (2006). "Hurricane John Discussion Eleven". NHC. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Brown/Knabb (2006). "Hurricane John Discussion Sixteen". Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ↑ Blake/Avila (2006). "Hurricane John Discussion Eighteen". NHC. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ↑ Beven (2006). "Hurricane John Discussion Nineteen". NHC. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ↑ Blake/Avila (2006). "Tropical Storm John Discussion 22". NHC. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- ↑ Roberts/Pasch (2006). "Tropical Depression John Public Advisory 26A". NHC. Retrieved 2006-09-03.

- ↑ Franklin (2006). "Tropical Depression John Discussion 29". NHC. Retrieved 2006-09-04.

- ↑ "Hurricane John grows to a Category 4 storm along Mexico's Pacific coast". Deseret News. Associated Press. 2006-08-30. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ↑ "Hurricane John Weakens To Category 3". CBS News. Associated Press. 2006-08-31. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ↑ Margot Habiby (2006-08-30). "Hurricane John Strengthens Off Mexico's Pacific Coast". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ↑ Melissa Baldwin (2006-08-30). "Hurricane John Threatens Mexican Riviera". Cruise Critic News. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ↑ Daniel Aguilar (2006). "Mexico orders evacuations as Hurricane John nears". Reuters. Retrieved 2006-08-31.

- 1 2 Steve Quinn (2006). "Remnants of Hurricane John douse El Paso". Associated Press. Retrieved 2006-09-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Associated Press (2006-09-05). "Hurricane John's remnants soak southern Texas and New Mexico, flooding roads as storm weakens". Archived from the original on 2013-02-10. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- 1 2 International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies (2006-08-30). "Mexico: Hurricane John Information Bulletin No. 1". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- 1 2 Antonio Alcantar (2006). "Hurricane John whips Mexico's Baja, power cut". Reuters. Retrieved 2006-09-02.

- 1 2 3 4 Sandra Dibble (2006). "200 families say homes destroyed by flooding". San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 2008-11-21. Retrieved 2006-09-08.

- 1 2 Malaysian Sun (2006). "Remnants of John could soak U.S. southwest". Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (2006). "Hurricane John leaves four dead, two missing in Mexico". Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- 1 2 Sandra Dibble (2006). "Baja towns still without utilities after tropical storm; three dead". San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 2013-02-02. Retrieved 2006-09-08.

- ↑ Associated Press (2006-09-16). "Hurricane Lane roars toward Baja". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ↑ Fabiola Martinez (2006). "Seis muertos y 2 desaparecidos por las lluvias en Durango y Tamaulipas" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2006-09-23.

- 1 2 Episcopal Relief and Development (2006). "ERD assists people affected by disasters in Mexico, Brazil and Ecuador". Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- 1 2 National Climatic Data Center (2006). "Event Report for Texas". Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ↑ Associated Press (2006-09-04). "After-Effects of Hurricane John Soak Texas, New Mexico". Fox News. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ↑ Alicia A. Caldwell (2006). "Continued rain soaks El Paso, nears record levels". Associated Press. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2006). "Event Report for Texas (2)". Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ↑ Lubbolk, TX National Weather Service (2006). "Labor Day Weekend is a wet one". Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ Albuquerque National Weather Service (2006). "A wet start to September 2006". Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ Associated Press (2006). "Hurricane John's remnants soak Texas, New Mexico". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ↑ Church World Service (2006). "Emergency Appeal: 2006 Summer Storms". Retrieved 2006-09-08.

- 1 2 David Marion (2006). "Tucsonans aid New Mexico flood victims". KVOA Tucson. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ↑ Associated Press (2006). "Hurricane leftovers cause minor flooding". Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- ↑ International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies (2006). "Mexico: Hurricane John Information Bulletin". Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- ↑ Baja California Sur (2006). "Baja California Sur Tourism Infrastructure Fully Operational After Hurricane John". Retrieved 2006-09-08.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane John (2006). |

- The NHC's archive on Hurricane John.