Hurricane Irene–Olivia

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Satellite image of Hurricane Olivia near peak intensity on September 25 | |

| Formed | September 11, 1971 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 30, 1971 |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 948 mbar (hPa); 27.99 inHg |

| Fatalities | 3 direct |

| Damage | > $1 million (1971 USD) |

| Areas affected | Lesser Antilles, Leeward Antilles, Central America (Nicaragua landfall), Mexico, Southwest United States |

| Part of the 1971 Atlantic and Pacific hurricane seasons | |

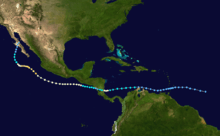

Hurricane Irene–Olivia was the first actively tracked tropical cyclone to move into the eastern Pacific Ocean from the Atlantic basin. It originated as a tropical depression on September 11, 1971, in the tropical Atlantic. The cyclone tracked nearly due westward at a low latitude, passing through the southern Windward Islands and later over northern South America. In the southwest Caribbean Sea, it intensified to a tropical storm and later a hurricane. Irene made landfall on southeastern Nicaragua on September 19, and maintained its circulation as it crossed the low-lying terrain of the country. Restrengthening after reaching the Pacific, Irene was renamed Hurricane Olivia, which ultimately attained peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). Olivia weakened significantly before moving ashore on the Baja California Peninsula on September 30; the next day it dissipated.

In the Atlantic, Irene produced moderate rainfall and winds along its path, although impact was greatest in Nicaragua where it moved ashore as a hurricane. A total of 96 homes were destroyed, and 1,200 people were left homeless. The rainfall resulted in widespread flooding, killing three people in Rivas. In neighboring Costa Rica, Hurricane Irene caused more than $1 million (USD) in damage to the banana crop. Later, the remnants of Hurricane Olivia produced rainfall in the southwest United States. Flooding was reported near Yuma, Arizona, which closed a major highway, and the moisture produced snowfall in higher elevations in the Rocky Mountains.

Meteorological history

The origins of the hurricane were from a tropical wave that exited the west African coast on September 7. It moved rapidly westward, developing into a tropical depression on September 11 about 800 miles (1300 km) east of the Windward Islands.[1] It was one of seven active tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin that day, one of the most active single days on record.[2] It existed at a fairly low latitude and failed to intensify due to the unfavorable combination of Hurricane Ginger and a long trough to its northwest.[1] On September 13, the depression passed just south of Barbados and subsequently entered the Caribbean Sea.[2] Interacting with the terrain of South America, the center became broad and ill-defined, although Curaçao reported winds of near tropical storm force as it crossed the island on September 16. It later moved near or over northern Venezuela and Colombia. As it approached the western Caribbean, the depression was able to organize more, with less influence from landmass or the trough to its north. At 0000 UTC on September 17, it is estimated the depression attained tropical storm status; that day, it was named Irene about 350 miles (560 km) east of San Andrés.[1] Initially, the storm was expected to track west-northwestward toward the northwest Caribbean, similar to the track taken by the destructive Hurricane Edith two weeks prior.[3]

Tropical Storm Irene gradually intensified as it continued across the southwestern Caribbean Sea. Late on September 18, the storm attained hurricane status a short distance off the coast of Central America, with 80 mph (130 km/h) winds, its peak intensity in the Atlantic Ocean.[4] As it strengthened, it developed an eye and spiral rainbands that extended across Panama into the Pacific Ocean.[1] Hurricane Irene weakened slightly as it approached the coast, although its pressure dropped to 989 mbar. On September 19, the hurricane made landfall in the Nicaraguan South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region;[4] it was the first tropical cyclone of hurricane intensity since 1911 to strike Nicaragua south of Bluefields.[1] Irene quickly weakened, deteriorating to tropical depression status within 18 hours of moving ashore.[4] The circulation remained organized over the low-lying terrain of southern Nicaragua, possibly due to it crossing Lake Nicaragua. After reaching the Pacific Ocean on September 20, the depression restrengthened to attain tropical storm status; upon doing so, it was re-designated by a new name, Olivia.[2][5] It was the first time an Atlantic hurricane was tracked as a tropical cyclone while crossing Central America into the Pacific Ocean;[6] subsequent research indicated there were earlier storms that accomplished the feat, although they were not known at the time.[4]

As an Eastern Pacific tropical cyclone, Olivia maintained well-defined outflow and inflow. It gradually intensified as it paralleled the southern Central America coastline. Late on September 21, a Hurricane Hunters flight reported winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and an eye 23 miles (37 km) in diameter; based on the readings, Olivia was upgraded to hurricane status. For several days, Olivia moved west to west-northwestward off the coast of Mexico, although its exact intensity fluctuations were unknown, due to lack of significant observations. On September 25, the eye became very pronounced on satellite imagery, and based on a report from the Hurricane Hunters, it is estimated Olivia reached peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h), about 245 miles (395 km) southwest of Manzanillo, Colima. The Hurricane Hunters also reported a pressure of 948 mbar, which was the lowest reported pressure during the 1971 Pacific hurricane season.[5]

The intensity of Hurricane Olivia fluctuated for two days as it turned westward away from land, due to a blocking ridge over northwestern Mexico. Early on September 26 it weakened to winds of about 105 mph (165 km/h), before it quickly restrengthened to its previous peak intensity. Subsequently, dry air became entrained in the circulation, and Olivia began to weaken as it moved over cooler waters. The eye became disorganized and eventually dissipated. Late on September 28 it weakened to tropical storm status, after beginning a turn to the northwest and later to the north. About 24 hours later, Olivia weakened to tropical depression status as it approached the coastline of the Baja California Peninsula. Most of the thunderstorm activity dissipated by the time the depression moved ashore on September 30; the next day, Olivia dissipated near the border of Baja California and Baja California Sur.[5]

Impact and records

As a tropical depression, the cyclone produced a wind gust of 43 mph (69 km/h) in Barbados. The system also dropped 3.35 inches (85.1 mm) of rainfall in Trinidad.[1] Prior to its arrival, officials noted the potential for the depression to bring flash flooding to northern Venezuela, as well as heavy rainfall to the ABC islands.[7] Later as a tropical storm, Irene brushed San Andrés island in the western Caribbean with gale force winds;[1] no major damage was reported there.[8]

Prior to the hurricane's landfall in Nicaragua, the country's army evacuated about 500 people from a settlement near Bluefields, and along the coastline, boats were advised to remain at port.[9] When it moved ashore, the hurricane produced sustained winds of 46 mph (74 km/h) in Bluefields.[1] The winds destroyed 27 houses in the region.[10] Observations were not available in the sparsely populated region near where Irene moved ashore, although winds were believed to have reached hurricane force there.[1] Reconnaissance planes reported heavy structural and tree damage in southeastern Nicaragua.[11] Satellite imagery suggested that heavy rainfall occurred from Panama through Honduras,[1] and one location in Nicaragua reported more than 6.3 inches (160 mm) of precipitation. The rainfall caused flooding in many communities, killing three people in Rivas. At least five rivers reported flooding; along one of the rivers, 35 houses were inundated, and along another, the floodwaters swept away all of the crops and personal belongings of three villages.[10] Across the country, the hurricane destroyed 96 homes,[11] and 1,200 people were left homeless.[10] In Costa Rica, Irene's passage resulted in more than $1 million (USD) in damage to the banana crop.[12]

Late in its duration, Hurricane Olivia brought increased moisture into the southwest United States. More than 2 inches (50 mm) of rainfall were reported across Arizona and New Mexico.[13] Light precipitation was also reported in western Texas and southeastern California.[14][15] The National Weather Service issued flash flood warnings throughout the region.[16] Near Yuma, Arizona, thunderstorms caused three major power outages and produced flooding that resulted in the closure of a portion of U.S. Route 95.[17] In Navajo and Pinal counties, the rainfall damaged roads, bridges, sewers, and homes, which amounted to about $250,000 in repair work for the state of Arizona.[18] The storm's moisture also produced locally heavy snowfall in higher elevations in the Rocky Mountains.[16]

Irene–Olivia is unusual in that it survived passage from the Atlantic to Pacific Ocean. Only nine other named storms are known to have done so.[19] Irene was the first of three Atlantic-to-Pacific crossover tropical cyclones in the 1970s, all three of which took eastern Pacific names starting with the letter O.[20]

See also

- Hurricane Joan–Miriam of 1988

- List of Atlantic–Pacific crossover hurricanes

- List of South America cyclones

- Other tropical cyclones named Irene

- Other tropical cyclones named Olivia

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 R.H. Simpson; John R. Hope (April 1972). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1971" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 100 (04): 256–267. Bibcode:1972MWRv..100..256S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1972)100<0256:AHSO>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- 1 2 3 R.H. Simpson; John R. Hope (April 1972). "Atlantic Tropical Systems of 1971" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 100 (04): 268–275. Bibcode:1972MWRv..100..268F. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1972)100<0268:ATSO>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- ↑ Staff Writer (1971-09-17). "Hurricane Edith on Irene Route". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- 1 2 3 4 National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division (April 11, 2017). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- 1 2 3 William J. Denny (April 1972). "Eastern Pacific hurricane season of 1971" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 100 (04): 276–293. Bibcode:1972MWRv..100..276D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1972)100<0276:EPHSO>2.3.CO;2. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (1971). "Annual Typhoon Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ Staff Writer (1971-09-15). "Edith Threatens Gulf Coast". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2015-12-03. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ↑ Diaz; et al. (April 1996). "Morphology and Marine Habitats of Two Southwestern Caribbean Atolls" (PDF). National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ Staff Writer (1971-09-20). "Storm Irene Loses Blow in Nicaragua". United Press International. Archived from the original on 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- 1 2 3 Dirección General de Meteorología (2008-07-07). "Huracán Irene (1971)" (in Spanish). Instituto Nicaragüense de Estudios Territoiales. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- 1 2 Staff Writer (1971-09-21). "Irene Reforming in Pacific Ocean". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2016-02-01. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ Staff Writer (1971-09-23). "Banana Crop is Hit by Hurricane Irene". The Chillicothe Constitution-Tribune. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ Robert E. Taubensee (December 1971). "Weather and Circulation of September 1971" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 99 (12): 986. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- ↑ Staff Writer (1971-10-01). "Major Weather Change Seen Possible in State". Avalanche-Journal. Archived from the original on 2015-11-26. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ Jack Williams (2005-05-17). "Background: California's tropical storms". USAToday.com. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- 1 2 Staff Writer (September 30, 1971). "Olivia brings rain, snow to western U.S.". United Press International. The Bryan Times. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ↑ Loren Listiak. "Heavy Storm Sneaks Into Town". The Yuma Daily Sun. Archived from the original on 2016-01-13. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- ↑ Pinal County Public Works. "Summary of Historical Hazards Impacting Pinal County Communities" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2009-06-14.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center (2013-06-18). Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2) (TXT) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ↑ Stephen Caparotta; D. Walston; Steven Young; Gary Padgett. "Subject: E15) What tropical storms and hurricanes have moved from the Atlantic to the Northeast Pacific or vice versa?". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

External links