Hurricane Greta–Olivia

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

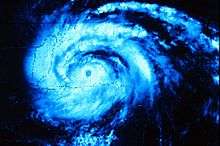

Hurricane Greta near peak intensity in the Gulf of Honduras on October 17 | |

| Formed | September 13, 1978 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 23, 1978 |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 130 mph (215 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 947 mbar (hPa); 27.96 inHg |

| Fatalities | 5 direct |

| Damage | $26 million (1978 USD) |

| Areas affected | Windward Islands, Central America (particularly Honduras), Belize, Mexico |

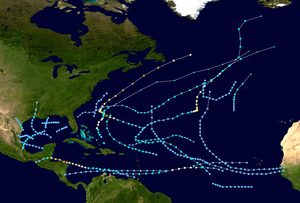

| Part of the 1978 Atlantic and Pacific hurricane seasons | |

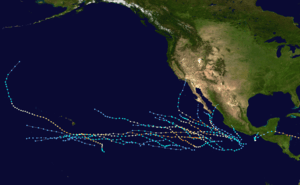

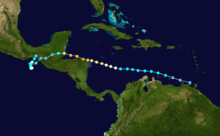

Hurricane Greta–Olivia was one of ten named Atlantic hurricanes to cross over Central America into the eastern Pacific while remaining a tropical cyclone. The seventh named storm of the 1978 Atlantic hurricane season, Greta formed from a tropical wave just northwest of Trinidad on September 13, and despite being in a climatologically unfavorable area, gradually intensified while moving west-northwestward. On September 16, it became a hurricane south of Jamaica. Two days later, the well-defined eye approached northeastern Honduras but veered to the northwest. After reaching peak winds of 130 mph (215 km/h) that day, Greta weakened while paralleling the northern Honduras coast just offshore. On September 19, it made landfall on Belize near Dangriga and quickly weakened into a tropical depression while crossing Guatemala and southeastern Mexico. After entering the eastern Pacific, the system re-intensified into a hurricane and was renamed Olivia, which weakened before dissipating over Chiapas on September 23.

Taking a similar path to Hurricane Fifi four years prior, Greta threatened to reproduce the devastating effects of the catastrophic storm; however, damage and loss of life was significantly less than feared. In Honduras, about 1,200 homes were damaged, about half of which in towns along the coastline. The storm damaged about 75% of the houses on Roatán along the offshore Bay Islands, and there was one death in the country. In the Belize Barrier Reef, Greta downed trees and produced high waves, while on the mainland, there was minimal flooding despite a high storm surge. In Dangriga where it made landfall, the hurricane damaged or destroyed 125 houses and the primary hospital. In Belize City, a tornado flipped over a truck and damaged four houses. Damage in Belize was estimated at $25 million (1978 USD), and there were four deaths.

Meteorological history

A tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa near Dakar, Senegal on September 7. Moving westward across the Atlantic Ocean, the wave spawned an area of convection three days later, which gradually organized. On September 13, the wave moved through the Windward Islands, producing wind gusts of 50 mph (85 km/h) on Barbados. Later that day, it is estimated the system developed into a tropical depression about 75 mi (120 km) west-northwest of Trinidad, based on ship and land reports. Though located in a climatologically unfavorable area, the depression intensified and continued to develop. A Hurricane Hunters flight on September 14 indicated that the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Greta to the north of the Netherlands Antilles.[1]

After becoming a tropical storm, Greta intensified slowly due to a strong trough to the northwest,[1] and with the South American coastline located to the south, the southerly inflow was disrupted.[2] With a ridge to the north along the 30th parallel, the storm moved quickly west-northwestward across the Caribbean.[3] On September 16, Greta intensified into a hurricane about 275 mi (443 km) south of Jamaica.[1] Shortly thereafter, the trough to the northwest weakened, which had been preventing the storm's intensification.[1] An increasingly well-defined eye developed while approaching the coast of Honduras as the barometric pressure quickly dropped.[4] Early on September 18, the eyewall passed just offshore Cabo Gracias a Dios, the sparsely populated border between Honduras and Nicaragua[4][5] The NHC described the eye as having "literally ricocheted off of the protruding northeast coast of Honduras", thus sparing much of the country from the strongest winds. At 0710 UTC on September 18, the Hurricane hunters observed a minimum pressure of 947 mbar (28.0 inHg) just off the northern Honduras coast, which was the basis for the estimated peak intensity of 130 mph (215 km/h).[4] This made it a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale.[6]

Despite the proximity to land, Greta initially maintained a well-defined structure. The hurricane continued generally west-northwestward due to the ridge to the north, and initially was expected to enter the Bay of Campeche.[7] After passing through the Bay Islands off northern Honduras,[5] Greta weakened slightly while approaching Belize, and made landfall near Dangriga at 0000 UTC on September 19,[4] with winds of about 110 mph (175 km/h).[6] The calm of the eye was reported for three to five minutes there.[8] Rapidly weakening over land, the hurricane deteriorated to tropical depression status over Guatemala within 12 hours of landfall. A large high pressure area from the Carolinas to the central Gulf of Mexico turned Greta southwestward toward the eastern Pacific Ocean.[9] At 0000 UTC on September 20, the Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center (EPHC) took over responsibility for issuing advisories while Greta was 30 mi (50 km) from the coast. Soon after, the depression emerged over the warm waters of the eastern Pacific and re-intensified. At 0600 UTC, the depression re-attained tropical storm status and named Olivia by the EPHC. After initially moving to the north, Olivia began executing a slow counterclockwise loop. Based on observations from nearby ships and radar, it is estimated Olivia attained hurricane status early on September 22. While tracking towards the Mexican coastline, the system weakened below hurricane threshold; between 1900 and 2000 UTC, Olivia made landfall about 60 mi (95 km) east of Salina Cruz. Early on September 23, Olivia dissipated over the Mexican state of Chiapas.[10]

Hurricane Greta–Olivia was a rare crossover storm from the Atlantic to the Pacific, one of ten named storms to maintain tropical cyclone status during the crossing.[6][11]

Impact

Early in its duration, Greta produced heavy rainfall in the Netherlands Antilles, but the strongest winds remained north of the island.[1]

Late on September 17 when Greta's eye was just offshore Honduras, the country's government issued a hurricane warning for the eastern coastline. Around the same time, the Mexican government issued a hurricane warning for the eastern Yucatán peninsula,[12] and on September 18 a hurricane warning was issued for the Belize and Guatemala coastlines.[13] These advanced warnings helped reduce fatalities.[9] In Puerto Castilla, Honduras, about 2,000 people were evacuated in advance of the storm.[14] The Honduran government put its military, police, and Red Cross on standby in advance of the storm, due to fears of a repeat of Hurricane Fifi in 1974.[15] However, unlike Fifi, which caused deadly floods in the region four years prior and took a similar track, Greta did not cause as significant river flooding in Honduras.[4][5]

Across much of Greta's track in Central America, the hurricane dropped locally heavy rainfall.[9] When Greta passed just offshore northeastern Honduras, it produced sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) in Puerto Lempira, with gusts to 115 mph (185 km/h). Winds along the northern Honduras coast were diminished due to the eyewall passing to the north.[4] In Honduras, meteorologists estimated that upwards of 15 in (380 mm) of rain fell in mountainous regions. Many villages were isolated and communication with them was severely hampered.[16] In Puerto Lempira, roughly 1,500 of the town's 7,000 residents sought refuge in five large structures during the storm.[17] In twelve communities along the coastline, military officials reported that 656 homes were destroyed, of which 278 were in Punta Potuca.[18] In the offshore Bay Islands, the hurricane destroyed 26 houses on Guanaja, where many roofs were lost and several boats were destroyed. On nearby Roatán, about 75% of the houses lost their roofs after experiencing wind gusts of 80 mph (130 km/h).[19] There was one death in Honduras,[9] and nationwide, the hurricane damaged about 1,200 homes, washed out roads and bridges, and wrecked coconut and rice crops.[20]

At Greta's final landfall in Belize, the highest sustained winds were 55 mph (89 km/h) in Belize City,[9] with gusts to 115 mph (185 km/h) at Dangriga near the landfall location.[21] On the offshore Ambergris Caye, winds reached 60 mph (97 km/h), and there was heavy rainfall.[22] On Half Moon Caye, the hurricane damaged the base of a lighthouse and knocked over several coconut trees.[23] Along the Belize Barrier Reef, the hurricane downed palm trees and produced high waves, with significant wave heights of about 33 ft (10 m) along Carrie Bow Caye.[24] On the mainland, storm tides in Dangriga were 6 to 7 ft (1.8 to 2.1 m) above normal, which did not cause much flooding.[9] The strong winds destroyed 50 houses there and unroofed a further 75,[8] including damage to the hospital. There were also disruptions to power and water service. About 90% of the grapefruit crop was destroyed, and 50% of the orange crop was lost.[25] Tides were 2 to 4 ft (0.61 to 1.22 m) above normal in Belize City,[9] which caused flooding in conjunction with swollen rivers.[25] The United States embassy was flooded with about one foot of mud.[26] There was little damage in the city,[25] although a tornado in Belize City that damaged four houses and flipped over a truck.[27] During the storm, the Belize International Airport was closed.[28] Farther inland, strong winds caused heavy damage at Guanacaste National Park.[23] Damage throughout Belize was estimated at $25 million (1978 USD), and there were four deaths.[9] Three of the deaths were on offshore islands in areas without radios, and the other was due to electrocution.[29]

Aftermath

Following the storm damage in Honduras, the country requested help from the United States. The Tactical Air Command had sent two squadrons to Central America in the middle of 1978, and in response to the request from Honduras, two aircraft delivered over 100,000 lb (45,000 kg) of cots, water, and generators; the units also deployed a 13–person crew who specialized in disaster relief. The aid was distributed by the Military of Honduras.[20]

In late October 1978, the United Methodist Church sent books and other supplies via aircraft to Belize, after a youth group rode out the storm there and desired to help residents.[30] Despite the hurricane damage, the economy of Belize continued to grow after Greta struck, including an increase in banana production.[31]

Although the National Hurricane Center does not consider it retired,[32] the World Meteorological Organization lists Greta in its retired hurricane name list.[33]

See also

- Other storms named Greta

- Other storms named Olivia

- List of Atlantic–Pacific crossover hurricanes

- Hurricane Edith (1971) - another hurricane that rapidly intensified while approaching Cape Gracias a Dios

- Hurricane Fifi-Orlene - hurricane in 1974 that caused catastrophic flooding in Honduras, before crossing into the Pacific and regenerating into a hurricane

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hurricane Greta and Hurricane Olivia Preliminary Report (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved 2013-12-17.

- ↑ John Hope (1978-09-14). Tropical Cyclone Discussion Tropical Storm Greta (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ↑ Paul Hebert (1978-09-15). Tropical Cyclone Discussion Tropical Storm Greta (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hurricane Greta and Hurricane Olivia Preliminary Report (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- 1 2 3 Miles B. Lawrence (January 1978). "North Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1978". Climatological Data: National Summary. 29. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- 1 2 3 National Hurricane Center (2013-06-18). Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2) (TXT) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ↑ John Hope (1978-09-20). Tropical Cyclone Discussion Hurricane Greta (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- 1 2 Alvin (1978-09-19). HWDamage (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hurricane Greta and Hurricane Olivia Preliminary Report (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ↑ Emil B. Gunther, Eastern Pacific Hurricane Center (July 1979). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1978" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society: 925–926. Bibcode:1979MWRv..107..911G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1979)107<0911:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ↑ Stephen Caparotta; et al. (2011-05-31). "Subject: E15) What tropical storms and hurricanes have moved from the Atlantic to the Northeast Pacific or vice versa?". Frequently Asked Questions. Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ↑ Paul Hebert (1978-09-17). Hurricane Greta Intermediate Advisory (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

- ↑ Joe Pelissier (1978-09-18). Hurricane Greta Intermediate Advisory (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

- ↑ "Hurricane Greta Loses Strength, Hits Belize on Journey Inland". The Evening Independent. Associated Press. 1978-09-19. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- ↑ "Hurricane Greta Pounds Honduras Coast". Kingman Daily Miner. Associated Press. 1978-09-18. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- ↑ Associated Press (1978-09-18). "Greta Downgraded to Tropical Storm". Spokane Daily Chronicle. p. 40. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ Associated Press (1978-09-17). "Winds, Rain Pound Honduras As Greta Hits Coast". Toledo Blade. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Associated Press (1978-09-19). "Hurricane Greta subsides after lashing two nations". Eugene Register-Guard. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ George Singer (1978-09-18). HWDamage7 (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-25.

- 1 2 "Bundles for Bolivia" (PDF). The Patriot. 439th Tactical Airlift Wing. 5 (12). December 1978. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-27. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- ↑ Miles B. Lawrence (1978-09-19). Report from Belize Weather Service (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ↑ George Singer (1978-09-18). HWDamage (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- 1 2 Lydia Waight; Judy Lumb (1999-02-20). The First Thirty Years (PDF) (Report). Belize Audubon Society. p. 44, 47. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- ↑ B. Kjerfve; S. P. Dinnel (May 1983). "Hindcast hurricane characteristics on the Belize barrier reef". Coral Reefs. 1 (4): 203. Bibcode:1983CorRe...1..203K. doi:10.1007/bf00304416. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- 1 2 3 George Singer (1978-09-19). HWDamage7 (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-25.

- ↑ "A Farewell to Charms" (PDF). U.S. Department of State Magazine. United States Department of State: 6. March 2007. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- ↑ George Singer (1978-09-18). HWDamage (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ↑ George Singer (1978-09-19). HWDamage (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ↑ Miles Lawrence (1978-09-23). HWDamage (JPG) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ↑ Ann Weldon (1978-11-11). "Mission of Mercy". The Evening Independent. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- ↑ Christine Vellos; Nigeli Sosa (October 1996). The Development of the Financial System of Belize (1970-1995) (PDF) (Report). Central Bank of Belize. p. 4. Retrieved 2013-12-26.

- ↑ Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names (Report). National Hurricane Center. 2013-04-11. Retrieved 2013-12-20.

- ↑ RA IV Hurricane Committee (2013-05-30). "Chapter 9: Tropical Cyclone Names". Regional Association IV: Hurricane Operational Plan 2013 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. pp. 98–99. Retrieved 2013-12-20.