Hurricane Bill (2009)

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Bill near peak intensity on August 19 | |

| Formed | August 15, 2009 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 26, 2009 |

| (Extratropical after August 24) | |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 130 mph (215 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 943 mbar (hPa); 27.85 inHg |

| Fatalities | 2 direct |

| Damage | $46.2 million (2009 USD) |

| Areas affected | Northeastern Caribbean, United States East Coast, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada, Europe |

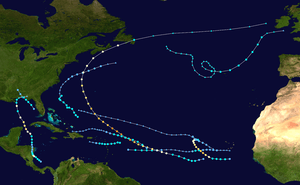

| Part of the 2009 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Bill was a large Atlantic tropical cyclone that brought minor damage across mainly Atlantic Canada and the East Coast of the United States during August 2009. The second named storm, first hurricane, and first major hurricane of the annual hurricane season, Bill originated from a tropical wave in the eastern Atlantic on August 15. Initially a tropical depression, the cyclone intensified within a favorable atmospheric environment, becoming Tropical Storm Bill six hours after formation. Steered west-northwest around the southern periphery of a subtropical ridge to the northeast of the cyclone, Bill passed through the central Atlantic. At 0600 UTC on August 17, the cyclone strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale; within 36 hours, Bill entered a period of rapid deepening and intensified into a major hurricane with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). Passing well northeast of the Lesser Antilles, Bill attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 130 mph (215 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 943 mb (hPa; 27.85 inHg) on August 19 and August 20, respectively. Thereafter, an approaching trough induced higher vertical wind shear across the region, causing slow weakening of the hurricane; this same trough resulted in an accelerated motion and curve northward. As the storm passed Bermuda, it contained sustained winds equal to a Category 2, and ultimately struck Newfoundland as a tropical storm. After moving inland and weakening to a tropical storm, Bill began an extratropical transition; this alteration in structure was completed by 1200 UTC on August 24. Two days later, Bill's remnant low was absorbed into a larger extratropical system over the Northern Atlantic.

Bill caused $46.2 million in damages and two deaths over a nine-day period. As it passed close to Bermuda, the hurricane caused power outages and strong winds, though damage was minor. Despite remaining well offshore of the United States East Coast, the storm's large wind field contributed to strong surf which caused severe beach erosion. Numerous offshore rescue operations occurred as a result of people swept away by the strong waves. All two deaths caused by the hurricane were the result of drownings off the U.S. coast. In some areas of New England, the storm's outer rainbands caused flash flooding. In Atlantic Canada, Bill caused mainly power outages and flooding events. Several roads were flooded in Nova Scotia, and 32,000 people lost power. In Newfoundland, where the hurricane made landfall, strong winds caused minor tree damage. As an extratropical system, Bill dropped light rainfall in the British Isles and Scandinavia.

Meteorological history

A tropical wave moved off the western coast of Africa on August 12, 2009, and entered the Atlantic Ocean. The National Hurricane Center (NHC) remarked upon the possibility for tropical cyclone development, as the wave had already been accompanied by a broad area of shower and thunderstorm activity.[1] The wave quickly organized, and a low pressure system formed to the south of the Cape Verde Islands on August 13.[2] The convection became slightly less organized on August 14,[3] though by early August 15, the NHC reported that a tropical depression was forming.[4] The system was declared Tropical Depression Three later that day.[5]

The newly designated depression continued to intensify, and it was quickly upgraded to Tropical Storm Bill.[6] Numerous rainbands had begun to develop, though the storm lacked deep convection near its center. At this time, Bill was already predicted to become a hurricane.[7] By early on August 16, the storm had developed what NHC forecasters described as a "beautiful" cloud pattern, and environmental conditions favored continued strengthening.[8] Bill intensified to attain Category 1 hurricane status on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale early on August 17.[9]

By late August 17, satellite imagery indicated that an eye feature may have been developing.[10] Bill sustained deep convection and well-established upper-level outflow;[11] it was upgraded to Category 2 status shortly before undergoing an eyewall replacement cycle.[12] Early August 18, the storm had established a very symmetric and well-organized appearance on satellite imagery, and a large, pronounced eye. The storm was moving west-northwestward under the steering currents of a subtropical ridge to the north.[13] Information derived from Hurricane Hunter reports and satellite imagery indicated that the storm had strengthened and reached Category 3 intensity on August 18, making it a major hurricane.[14] Despite some wind shear, Bill was upgraded further to Category 4 intensity on August 19 and reached maximum size with hurricane-force winds extending 115 miles (185 km) and tropical storm force winds extending 290 miles (470 km) from the center[15]

On August 20, the storm began to weaken, being downgraded to a Category 3, as convection associated with it diminished somewhat.[16] The storm's eyewall also weakened, with a portion of it dissipating later that day. Shear also deteriorated the structure of the storm, with clouds being displaced from the main circulation.[17] However, shortly after, the eye became much better defined and developed several mesovortices, a feature typical of intense hurricanes.[18] On August 21, Bill was downgraded to a Category 2 hurricane as the structure of the storm deteriorated; however, the atmospheric pressure in the eye was 954 mbar (hPa) at that time, equivalent to a strong Category 3 storm.[19] By the morning of August 22, the hurricane completed an eyewall replacement cycle and featured a 55 mi (89 km) wide eye.[20]

Later on August 22, the storm weakened to a Category 1 hurricane as Bill tracked over cooler waters.[21] The storm maintained its intensity through August 23 as it retained its cloud-filled eye and tracked at a quick pace to the north-northeast producing 26.4 m (87 ft) waves at La Have Bank Buoy (station 44142) 42°30′N 64°01′W / 42.5°N 64.02°W[22] and 16 ft surge on coastlines in New England and Nova Scotia.[23] The storm then made landfall shortly before midnight local time, at Point Rosie, on the Burin Peninsula of Newfoundland as 70 mph (110 km/h) tropical storm.[24] Shortly after this it was downgraded to a tropical storm, and then lost tropical characteristics.[25] The remnants of Bill crossed the Atlantic Ocean as an extratropical storm and later impacted the United Kingdom with heavy rain and surf.[26] On August 26, the remnants of Hurricane Bill were absorbed by a larger extratropical cyclone, near the British Isles.[24]

Preparations

Bermuda

On August 18, the Emergency Measures Organisation (EMO) of Bermuda advised the public to begin preparing for Hurricane Bill. Derrick Binns, Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Labour, Home Affairs and Housing, reported that "We have been following the storm closely since its inception, and today we reviewed our planning and procedures to ensure all are in sync. While we have not as yet issued hurricane warnings, I think it is important to advise residents to check their emergency kits to be sure supplies are adequate."[27] Residents on the island were instructed to review their emergency supplies, while boat owners were urged to secure their watercrafts.[28] By August 20, preparations had expanded as the projected path of Bill was to pass 200 miles west-southwest of the British overseas territory early on August 22.[29] Late on August 21, The Causeway bridge linking the eastern parish of St. Georges was closed as well as L.F. Wade International Airport. Ferry service was cancelled until August 23.[30] Late on August 21, tropical storm force winds were observed in Bermuda with some gusts above hurricane force.[31]

United States

In response to predictions of rough surf and rip currents, the Atlantic Beach, North Carolina fire department planned to increase the number of on-duty lifeguards.[32] On Long Island, New York, local officials began tracking Hurricane Bill and initiating preparations.[33] Local crew workers trimmed trees to reduce the amount of airborne debris. On August 17, the United States Army assessed 30 key buildings for power needs. Residents were urged to stock up on food and emergency supplies as officials estimated that in the event of a hurricane emergency, nearly 650,000 people would not have access to shelter. The Suffolk County Red Cross began organizing catering agencies to prepare meals to supply shelters.[33] The Long Island Power Authority also took preventative measures.[34]

On August 20, the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency made several conference calls with the National Weather Service about possible impacts from the storm in the state, particularly in Cape Cod.[35] Bill came close enough to the region to warrant a tropical storm warning for a while.[20]

Canada

Peter Bowyer, Program Supervisor of the Canadian Hurricane Centre, advised Nova Scotia residents to monitor the storm's progress and take necessary precautions. He said it is "almost inevitable that the storm will find some part of Eastern Canada. Whether that’s the marine areas or the land district, it's still too far to say."[36] Dozens of flights were canceled ahead of the storm at Halifax Stanfield International Airport and ferry service between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland was temporarily canceled.[37] Offshore, the Exxon Mobil corporation evacuated nearly 200 personnel from a project near Nova Scotia as a precaution.[38] On August 22, officials announced that all parks in Nova Scotia would be closed for the duration of Hurricane Bill.[39]

On August 22, Environment Canada, the meteorological agency of Canada, issued a tropical storm warning from Charlesville in Shelburne County, Nova Scotia eastward to Ecum Secum in the Halifax Regional Municipality. A hurricane watch was issued for areas between Ecum Secum eastward to Point Aconi. The remaining north coast of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and western Newfoundland were placed under a tropical storm watch.[40] Several hours later, the tropical storm warning was extended to include the areas under a hurricane watch and most of Newfoundland was placed under a tropical storm watch.[41] Early on August 23, a tropical storm warning was issued in Newfoundland for areas between Stone's Cove and Cape Bonavista.[42] About 150 people were evacuated from two senior homes in Newfoundland and the town of Placentia was put under a state of emergency in fears of storm surge damage.[43]

Republic of Ireland and United Kingdom

On August 25, Met Éireann issued gale warnings across the south of Ireland, and advised small boats not to go out to sea until the system had passed. They also forecast up to 1 in (25 mm) of rain across Ireland.[44] The Met Office in the UK issued severe weather warnings in preparation for the arrival of the storm.

Impact

On August 19, Peter Bray, a British rower attempting to break the record for the quickest solo crossing of the Atlantic was forced to abandon his boat and board the RRS James Cook due to being in the path of Hurricane Bill.[45] Large, life-threatening swells produced by the storm impacted north-facing coastlines of Puerto Rico and Hispaniola as Hurricane Bill approached Bermuda.[46][47]

United States

In Massachusetts, outer bands of Hurricane Bill produced significant amounts of rainfall, peaking at 3.74 in (95 mm) in Kingston, Massachusetts. Most areas along the eastern portion of the state received rain during the night of August 22 into the morning of August 23, with several areas exceeding 2 in (51 mm).[48] On Long Island, beach damage was severe; in some areas the damage was the worst since Hurricane Gloria in 1985. Along the coasts of North Carolina, waves averaging 10 ft (3.0 m) in height impacted beaches. In Wrightsville Beach, up to 30 rescues were made due to strong rip currents and large swells; however, only one incident resulted in hospitalization. Severe beach erosion took place at Bald Head Island, where 150 ft (46 m) of beach was washed away, resulting in the loss of the remaining sea turtle nests.[49]

Along the coastlines of Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware, waves were estimated to have reached 8 ft (2.4 m) at the height of the event.[50] Beaches along the Georgia coastline, located nearly 600 mi (970 km) from Bill, recorded large swells from the storm and strong rip currents.[51] In Delaware, waves peaked near 10 ft (3.0 m), resulting in one serious injury after a man was tossed by a wave and thrown face-first into the sand.[52]

Waves along the Georgia coast averaged 5 to 6 ft (1.5 to 1.8 m) in height with some reaching 8 ft (2.4 m). This resulted in numerous lifeguard rescues and some minor coastal flooding.[53] Beaches along Long Island were closed after waves up to 12 ft (3.7 m) began to cause coastal flooding and beach erosion.[54] All beaches around New York City were closed due to the risk of strong rip currents and waves up to 20 ft (6.1 m).[55] In southern New York, a cold front stalled by Hurricane Bill produced torrential rainfall, amounting to at least 2 in (51 mm) in a few hours, causing flash flooding and a tornado in Maine. Lightning produced by severe thunderstorms also left 5,000 residences without power.[56]

A 54-year-old man drowned at New Smyrna Beach, Volusia County, Florida due to the heavy surf.[57] In New York, severe beach erosion caused by the storm resulted in over $35.5 million in losses.[58] A 7-year-old girl drowned after she, her father, and a 12-year-old girl were swept off a rocky ledge near Acadia National Park in Maine on August 23.[59] The three were part of an early afternoon crowd of thousands who lined the Maine's national park's rocky shoreline to watch the high surf and crashing waves. Authorities said that about 20 people were swept away, but 17 of them made back to shore safely. Eleven were sent to area hospitals for spinal cord injuries.[60]

Two lifeguards at Mecox Beach in Watermill, New York accompanied endurance artist David Blaine back to shore after he was allegedly caught in a rip current after ignoring signs and verbal warnings not to swim in the ocean on August 23. Blaine said he was not in trouble and did not need the rescue.[61][62][63]

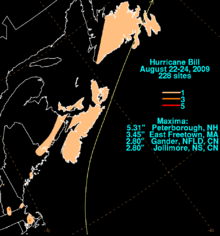

Further inland, a band of heavy rain fueled by tropical moisture from Bill produced upwards of 5 in (130 mm) in southern New Hampshire during an eight-hour span. The intense rainfall led to significant flash flooding that covered several roads and inundated homes.[64] Mudslides also closed roads in portions of the state as hillsides collapsed. Seven people required water rescue after their cars stalled in floodwaters. Overall, the floods left roughly $700,000 in damages in New Hampshire but no fatalities or injuries.[64][65][66]

Bermuda and Atlantic Canada

The hurricane had little impact in Bermuda. A public high school was designated as an emergency shelter, into which The Salvation Army took six homeless people. Some 3,700 households experienced power outages at some point during the storm, and in some instances cable television and internet services were also interrupted, particularly in the central Spanish Point headland. During the daytime on Saturday, public works crews performed cleanup of light debris, mostly discarded garbage unveiled by the storm.[67]

By the afternoon of August 23, up to 2.3 in (58 mm) of rain had fallen in southern Nova Scotia.[68] At least 32,000 residences in Nova Scotia had lost power due to the storm.[69] At the height of the storm, 45,000 people were without power and rainfall rates reached 1.2 in/h (30 mm/h). Several roads were flooded and overall damage was considered minor. Three people were injured by large waves and a gift shop and a home were badly damaged while a fish shed and breakwater were destroyed at Peggys Cove after being washed away by a 33 ft (10 m) wave.[70] Offshore, a buoy measured waves up to 85 ft (26 m).[71] Winds in Nova Scotia were recorded up to 50 mph (85 km/h) with higher gusts.[72]

In Newfoundland, the Avalon Peninsula experienced the highest winds from Hurricane Bill. A wind gust of 80 mph (130 km/h) was recorded in Cape Race. In St. John's, trees were blown down by the strong winds. However, rains from Bill mostly affected central areas of the island, where rainfall peaked at 2.75 in (70 mm) in Gander.[73] Rains washed out roads, and was responsible for some localized freshwater flooding.[74] Other areas of the central and southern coasts also received rain.[73] Damage from the storm throughout Atlantic Canada reached $10 million.[75]

British Isles and Scandinavia

Throughout the British Isles, the remnants of Bill produced high winds and heavy rains. All of Ireland and most of the United Kingdom was affected by the storm in some way. Rainfall in the United Kingdom peaked at 31 mm (1.2 in) in Shap.[76] After passing through the British Isles, the remnant system affected parts of Scandinavia before dissipating.[77]

See also

- Tropical cyclone effects in Europe

- Hurricane Earl (2010)

- Hurricane Edouard (1996)

- Hurricane Katia

- List of Canada hurricanes

- List of New England hurricanes

- List of Category 4 Atlantic hurricanes

References

- ↑ Blake (August 12, 2009). "August 12, 2009 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ↑ Avila (August 13, 2009). "August 13, 2009 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ↑ Beven (August 14, 2009). "August 14, 2009 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ↑ Blake (August 15, 2009). "August 15, 2009 Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ↑ Beven (August 15, 2009). "Tropical Depression Three Advisory Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ↑ Avila (August 15, 2009). "Tropical Storm Bill Advisory Number 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ↑ Avila (August 15, 2009). "Tropical Storm Bill Advisory Number 3". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ↑ Blake (August 16, 2009). "Tropical Storm Bill Advisory Number 5". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ↑ Kimberlain (August 17, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Advisory Number 8". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ↑ Brennan/Roberts (August 17, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Advisory Number 10". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ↑ Kimberlain/Pasch (August 17, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Advisory Number 11". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ↑ Beven (August 18, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Advisory Number 12". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ↑ Brown/Cangialosi (August 18, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Advisory Number 13". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ↑ Kimberlain/Pasch (August 18, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Advisory Number 15". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ↑ Beven (August 19, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Advisory Number 16". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ↑ Jack Beven (August 20, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Discussion Twenty". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (August 20, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Discussion 21". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila and Eric Blake (August 20, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Discussion 22". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (August 21, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Discussion 26". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- 1 2 Jack Beven (August 22, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Discussion 28". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (August 22, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Discussion 30". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ↑ End/Nickerson/Fogarty/Mercer (August 23, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Intermediate Information Statement". Canadian Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ↑ Dan Brown (August 23, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Discussion 32". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- 1 2 http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL032009_Bill.pdf

- ↑ Brown/Roberts (August 24, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Discussion 36". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ↑ "British Isles: Infrared satellite". metoffice.gov.uk. Retrieved 2009-08-25.

- ↑ "People urged to prepare for Hurricane Bill today". The Royal Gazette. August 18, 2009. Archived from the original on September 4, 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ↑ Nadia Arandjelovic (August 19, 2009). "EMO reports it's taking Hurricane Bill 'very seriously'". The Royal Gazette. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ↑ Owain Johnston-Barnes (August 21, 2009). "Island prepares for Hurricane Bill". The Royal Gazette. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ↑ Dale, Amanda (August 21, 2009). "Hurricane Bill disrupts airport and ferry services". The Royal Gazette. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ↑ Brennan (August 21, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Advisory Number 27". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2010-06-25.

- ↑ Christine Kennedy (August 18, 2009). "Hurricane Bill = Strong Rip Currents". WITN. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- 1 2 Mitchell Freedman and Deborah S. Morris (August 17, 2009). "Long Island officials prepare for hurricane season". NewsDay. Archived from the original on August 19, 2009. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- ↑ Claude Solnik (August 18, 2009). "LIPA preps for potential hurricane hit". Long Island Business News. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ↑ Staff Writer (August 20, 2009). "WBURMass. Officials Prepare For Hurricane Bill Impact". WBUR. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ↑ Hilary Beaumont (August 19, 2009). "Hurricane centre warns Nova Scotians to 'get ready'". Metro Halifax. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ↑ Staff Writer (August 23, 2009). "Bill marches into Atlantic Canada". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Christopher Martin (August 21, 2009). "Exxon Mobil Evacuating Sable Gas Field Ahead of Hurricane Bill". Bloomberg News.

- ↑ Kevin Jess (August 22, 2009). "article imageHurricane Bill closes Nova Scotia Parks". Digital Journal. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (August 22, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Public Advisory 29". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila and Michael Brennan (August 22, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Public Advisory 30". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Dan Brown and David Roberts (August 23, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Public Advisory 32". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Michael MacDonald (August 24, 2009). "Bill all bluster, no bite". The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on August 24, 2009. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ↑ Alex Morales (August 25, 2009). "Hurricane Bill’s Remnants Prompt Irish, British Gale Warnings". Bloomberg News.

- ↑ "Hurricane forces rower to abandon Atlantic crossing". CBC News. August 19, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (August 22, 2009). "Bermuda placed on alert as Hurricane Bill advances". Taiwan News. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Names". National Hurricane Center. 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-12-07. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ↑ National Weather Service (August 23, 2009). "Public Information Statement: Hurricane Bill Rainfall". Weather Underground. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Shelby Sebens (August 22, 2009). "No deaths or major damage as hurricane Bill passes". Star News. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Emma Brown (August 22, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Whips Up Waves Along Local Coastlines". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Justin Burrows (August 22, 2009). "Hurricane Bill makes waves off Tybee". WTOC11. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Beth Miller (August 22, 2009). "Wave surges pound Rehoboth Beach". The News Journal. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Sheila Parker (August 22, 2009). "Dangerous Conditions At Tybee". WSAV3. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Staff Writer (August 22, 2009). "Hurricane Bill Closes Southampton Town Beaches". The Sag Harbor Express'. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Adam Lisberg and Rich Schaprio (August 21, 2009). "Hurricane Bill forces city to close beaches in Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Ken Valenti (August 23, 2009). "Cold front stalled by Hurricane Bill floods roadways". 'Lower Hudson News. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Rough Waves, Rip Currents Make For Dangerous Beaches". American Broadcasting Company. WFTV. August 23, 2009. Archived from the original on August 26, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ↑ Russell Drumm (December 3, 2009). "Federal, State Funds Sought for Damage". The East Hampton Star. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ↑ "7-year-old girl dies after being swept away.". AP. August 23, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ↑ Bronis, Jason (August 23, 2009). "Coast Guard says girl swept to sea by wave dies". The Associated Press. The Associated Press via Google News. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ↑ Jordan, Sarah; Fasick, Kevin; Algar, Selim (September 2, 2009). "Livid Long I. Lifeguards Blast Houdummy Blaine". New York Post. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ↑ DAVID BLAINE: RESCUE TALK ALL WET - New York Post - August 25, 2009

- ↑ Johnson, Richard; Steindler, Corynne; Neel Shah (September 2, 2012). "David Blaine: Rescue Talk All Wet". New York Post. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- 1 2 Stuart Hinson (2009). "New Hampshire Event Report: Flood". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ↑ Stuart Hinson (2009). "New Hampshire Event Report: Flash Flood". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ↑ Stuart Hinson (2009). "New Hampshire Event Report: Flash Flood". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Breaking News WITH VIDEO: Flights affected, Causeway open, buses back, power being restored". The Royal Gazette. August 22, 2009. Archived from the original on August 27, 2009. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ↑ Staff Writer (August 23, 2009). "N.S. under heavy downpour as hurricane Bill marches into Atlantic Canada". The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ The Canadian Press (August 23, 2009). "Hurricane Bill knocks out power as it marches through Atlantic Canada". The Canadian Press. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Hurricane Bill Weakens in Newfoundland" CBC Radio August 24, 2009

- ↑ Staff Writer (August 24, 2009). "Nova Scotia 'lucky' after Hurricane Bill: EMO minister". CBC News. Archived from the original on August 24, 2009. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ↑ Michael Macdonald (August 23, 2009). "L'ouragan Bill n'a pas occasionné autant de dommages que prévu en N.-E." (in French). La Presse Canadienne. Archived from the original on August 31, 2009. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- 1 2 "Tropical storm Bill soaks Newfoundland". CBC News. August 25, 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion A. (October 21, 2--0). "Hurricane Bill" (PDF). Tropical Cyclone Report. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 December 2012. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Glenn McGillivary (January 2010). "Annus Horriblis, The Sequel" (PDF). Institute for Catastrophe Loss Reduction. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ↑ Laura Harding (August 27, 2009). "More rain expected in parts of UK". The Independent. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ↑ "Rain storms as Hurricane Bill hits Britain". Metro. August 27, 2009. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

External links

| Wikinews has related news: Hurricane Bill now a Category 4 storm |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Bill (2009). |

- Canadian Hurricane Center of the Meteorological Service of Canada

- Others

- Near Real Time and Composite Satellite Imagery for Bill by Earth Snapshot

- Latest satellite imagery of a tropical system by NOAA