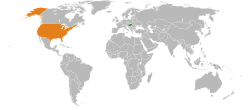

Hungary–United States relations

| |

Hungary |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic Mission | |

| Hungarian Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Budapest |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Réka Szemerkényi | Vacant |

Hungary – United States relations are bilateral relations between Hungary and the United States.

According to the 2012 U.S. Global Leadership Report, 38% of Hungarians approve of U.S. leadership, with 20% disapproving and 42% uncertain, a decrease from 53% approval in 2011.[1]

Country comparison

| Name | Hungary | United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official name | Hungary (Magyarország) | United States of America | ||

| Coat of Arms |  |

.svg.png) | ||

| Flag |  |

| ||

| Population | 9,830,485 | 324,720,797 | ||

| Area | 93,028 km2 (35,919 sq mi) | 9,525,067 km2 (3,677,649 sq mi) | ||

| Population Density | 105.9/km2 (274.3/sq mi) | 35/km2 (90.6/sq mi) | ||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic | Federal presidential constitutional republic | ||

| Capital | Budapest – 1,759,407 (2,524,697 Metro) | Washington, D.C. | ||

| Largest City | New York City – 8,550,405 (20,182,305 Metro) | |||

| Official language | Hungarian (de facto and de jure) | None (English de facto) | ||

| Main religions | 38.9% Catholicism (Roman, Greek), 13.8% Protestantism (Reformed, Evangelical), 0.2% Orthodox, 0.1% Jewish, 1.7% other, 16.7% Non-religious, 1.5% Atheism, 27.2% undeclared | 70.6% Christian, 1.9% Jewish, 0.9% Islam, 0.7% Buddhist, 2.5% other faiths; 22.8% Irreligious | ||

| Ethnic groups | 83.7% Hungarian, 3.1% Roma, 1.3% German; 14.7% not declared | 72.4% White, 12.6% Black, 9.1% Multiracial/Other, 4.8% Asian, 0.9% Native, 0.2% Islanders | ||

| GDP (nominal) | $132.683 billion, $13,487 per capita | $18,558.000 billion, $57,220 per capita | ||

| External debt (nominal) | $202.000 billion (2012 Q4) – 115 % of GDP | $17,910.859 billion (2016 Q1) – 96 % of GDP | ||

| GDP (PPP) | $265.037 billion, $26,941 per capita | $18,558.000 billion, $57,220 per capita | ||

| Currency | Hungarian forint (Ft) – HUF | United States dollar ($) – USD | ||

| Human Development Index | 0.828 (very high) | 0.915 (very high) | ||

| Expatriate populations | ? | 1,563,081 persons of Hungarian ancestry lived in the USA |

History

Until 1867 the Kingdom of Hungary had been a part of the Austrian Empire and from 1867 to 1918 of the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. United States diplomatic relations with Hungary were conducted through the United States Ambassador to Austria in Vienna. After the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire following World War I, Hungary and the United States established bilateral relations through a legation in Budapest established in 1921. The first American ambassador to Hungary (Theodore Brentano) was appointed on February 10, 1922.

Diplomatic relations were interrupted at the outbreak of World War II. Hungary severed relations with the U.S. on December 11, 1941, when the United States declared war on Germany. Two days later, on December 13, Hungary declared war on the United States. The embassy was closed and diplomatic personnel returned to the U.S.

Normal bilateral relations between Hungary and the U.S. were resumed in December 1945 when a U.S. ambassador was appointed and the embassy was reopened.

Relations between the United States and Hungary following World War II were affected by the Soviet armed forces' occupation of Hungary. Full diplomatic relations were established at the legation level on October 12, 1945, before the signing of the Hungarian peace treaty on February 10, 1947. After the communist takeover in 1947-48, relations with Hungary became increasingly strained by the nationalization of U.S.-owned property and what the United States considered unacceptable treatment of U.S. citizens and personnel. As well as restrictions on the operations of the American legation. Though relations deteriorated further after the suppression of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, an exchange of ambassadors in 1966 inaugurated an era of improving relations. In 1972, a consular convention was concluded to provide consular protection to U.S. citizens in Hungary.

In 1973, a bilateral agreement was reached under which Hungary settled the nationalization claims of American citizens. On 6 January 1978, the United States returned the Holy Crown of Hungary, which had been safeguarded by the United States since the end of World War II. Symbolically and actually, this event marked the beginning of excellent relations between the two countries. A 1978 bilateral trade agreement included extension of most-favored-nation status to Hungary. Cultural and scientific exchanges were expanded. As Hungary began to pull away from the Soviet orbit, the United States offered assistance and expertise to help establish a constitution, a democratic political system, and a plan for a free market economy.

Between 1989 and 1993, the Support for East European Democracy (SEED) Act provided more than $136 million for economic restructuring and private-sector development. The Hungarian-American Enterprise Fund has offered loans, equity capital, and technical assistance to promote private-sector development. The U.S. Government has provided expert and financial assistance for the development of modern and Western institutions in many policy areas, including national security, law enforcement, free media, environmental regulations, education, and health care. American direct investment has had a direct, positive impact on the Hungarian economy and on continued good bilateral relations. When Hungary acceded to NATO in April 1999, it became a formal ally of the United States. This move has been consistently supported by the 1.5 million-strong Hungarian-American community. The U.S. government supported Hungarian accession to the European Union in 2004, and continues to work with Hungary as a valued partner in the Transatlantic relationship. Hungary joined the Visa Waiver Program in 2008.

High-level mutual visits

Visits from Hungary to the United States

- Prime Minister József Antall (1990)

- Prime Minister Gyula Horn (1995)

- Prime Minister Viktor Orbán (2001)

- Prime Minister Péter Medgyessy (2004)

- Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány (2005)

- Prime Minister Gordon Bajnai (2009)

- President László Sólyom (2006)

Visits from the United States to Hungary

- President George H. W. Bush (1989)

- President Bill Clinton (1994, 1996)

- President George W. Bush (2006)

Resident diplomatic missions

- of Hungary in the United States

- Embassy[2] (1): Washington, D.C.

- Consulate General (3): Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City

- Honorary Consulate General (1): Atlanta

- Consulate Honorary (18): Boston, Cleveland, Denver, Hampden, Honolulu, Houston, Mayagüez, Mercer Island, Miami, New Orleans, Portland, Sacramento, St. Louis, St. Louis Park, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, Sarasota, Charlotte

- of the United States in Hungary

Sister-Twinning cities

- Budapest and

New York City, New York

New York City, New York - Miskolc and

Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland, Ohio - Pécs and

Seattle, Washington /

Seattle, Washington /  Tucson, Arizona

Tucson, Arizona - Siófok and

Walnut Creek, California

Walnut Creek, California - Szeged and

Toledo, Ohio

Toledo, Ohio - Tatabánya and

Fairfield, Connecticut

Fairfield, Connecticut - Tokaj and

Sonoma, California

Sonoma, California

See also

References

- ↑ U.S. Global Leadership Project Report - 2012 Gallup

- ↑ Embassy of Hungary in Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Embassy of United States in Budapest

Further reading

- Borhi, László, "In the Power Arena: U.S.-Hungarian Relations, 1942–1989," The Hungarian Quarterly (Budapest), 51 (Summer 2010), pp 67–81.

- Borhi, László. Hungary in the Cold War, 1945-1956: Between the United States and the Soviet Union (2004) online

- Frank, Tibor. Ethnicity, Propaganda, Myth-Making: Studies in Hungarian Connections to Britain and America, 1848–1945 (Budapest, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1999).

- Gati, Charles. Hungary and the Soviet Bloc (Duke University Press, 1986).

- Glant, Tibor, "Ninety Years of United States-Hungarian Relations," Eger Journal of American Studies, 13 (2012), 163–83.

- Glant, Tibor, "The Myth and History of Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points in Hungary," Eger Journal of American Studies (Eger), 12 (2010), 301–22.

- Horcicka, Václav, "Austria-Hungary, Unrestricted Submarine Warfare, and the United States' Entrance into the First World War," International History Review (Burnaby), 34 (June 2012), 245–69.

- Lévai, Csaba, "Henry Clay and Lajos Kossuth's Visit in the United States, 1851–1852," Eger Journal of American Studies (Eger), 13 (2012), pp 219–41.

- Max, Stanley. The Anglo-American Response to the Sovietization of Hungary, 1945– 1948 (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1990).

- Peterecz, Zoltán, "'A Certain Amount of Tactful Undermining': Herbert C. Pell and Hungary in 1941," The Hungarian Quarterly (Budapest), 52 (Spring–Summer 2011), pp 124–37.

- Peterecz, Zoltán, "American Foreign Policy and American Financial Controllers in Europe in the 1920s," Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (Debrecen), 18 (2012), pp 457–85.

- Peterecz, Zoltán, "Money Has No Smell: Anti-Semitism in Hungary and the Anglo-Saxon World, and the Launching of the International Reconstruction Loan for Hungary in 1924," Eger Journal of American Studies (Eger), 13 (2012), pp 273–90.

- Peterecz, Zoltán, "The Fight for a Yankee over Here: Attempts to Secure an American for an Official League of Nations Post in the Postwar Central European Financial Reconstruction Era of the 1920s," Eger Journal of American Studies (Eger), 12 (2010), pp 465–88.

- Radvanyi, Janos. Hungary and the Superpowers, The 1956 Revolution and Realpolitik (Stanford University Press, 1972).

- Romsics, Ignác, ed. Twentieth Century Hungary and the Great Powers (Boulder: East European Monographs, 1996).

- Sakmyster, Thomas L. (1994). Hungary's Admiral on Horseback: Miklós Horthy, 1918–1944. Boulder: East European Monographs.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of State website http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/index.htm (Background Notes).

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of State website http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/index.htm (Background Notes).