Hundred Years' War (1369–89)

| Hundred Years' War (1369-1389) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Hundred Years' War | |||||||

The Battle of Pontvallain | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The Caroline War was the second phase of the Hundred Years' War between France and England, following the Edwardian War. It was so-named after Charles V of France, who resumed the war nine years after the Treaty of Brétigny (signed 1360).

In May 1369, the Black Prince, son of Edward III of England, received summons from the French king demanding his presence in Paris. The prince refused, and Charles responded by declaring war. He immediately set out to reverse the territorial losses imposed at Brétigny and he was largely successful in his lifetime. His successor, Charles VI, made peace with the son of the Black Prince, Richard II, in 1389. This truce was extended many times until the war was resumed in 1415.

Background

In the Treaty of Brétigny, Edward III renounced his claim to the French throne in exchange for the duchy of Aquitaine in full sovereignty. Between the nine years of formal peace between the two kingdoms, the English and French clashed in Brittany and Castile.

In the War of the Breton Succession, the English backed the heir male, the House of Montfort (a cadet of the House of Dreux, itself a cadet of the Capetian dynasty) while the French backed the heir general, the House of Blois. Since Brittany allowed female succession, the French considered the Blois side to be the rightful heir. The war began in 1341, but the English continued backing the Montforts even after the Peace of Brétigny. The English-supported claimant John of Montfort defeated and killed the French claimant, Charles of Blois, at the Battle of Auray in 1364. By that time, however, Edward III no longer had a claim to the throne of France, so John had to accept the suzerainty of the French king in order to hold his duchy in peace. Thus, the English derived no benefit from their victory. In fact, the French received the benefit of improved generalship in the person of the Breton commander Bertrand du Guesclin, who, leaving Brittany, entered the service of Charles and became one of his most successful generals.

With peace in France, the mercenaries and soldiers lately employed in the war became unemployed, and turned to plundering. Charles V also had a score to settle with Pedro the Cruel, King of Castile, who married his sister-in-law, Blanche of Bourbon, and had her poisoned. Charles V ordered Du Guesclin to lead these bands to Castile to depose Pedro the Cruel. The Castilian Civil War ensued. Du Guesclin succeeded in his object; Henry of Trastámara was placed on the Castilian throne.

Having been opposed by the French, Pedro appealed to the Black Prince for aid, promising rewards. The Black Prince succeeded in restoring Pedro following the Battle of Nájera. But Pedro refused to make payments, to the chagrin of this English and Navarrese allies. Without them, Pedro was once more deposed, and lost his life. Again the English gained nothing from their intervention, except the enmity of the new king of Castile, who allied himself with France.

The Black Prince's intervention in the Castilian Civil War, and the failure of Pedro to reward his services, depleted the prince's treasury. He resolved to recover his losses by raising the taxes in Aquitaine. The Gascons, unaccustomed to such taxes, complained. Unheeded, they turned to the King of France as their feudal overlord. But by the Treaty of Brétigny the King of France had lost his suzerainty over Aquitaine. After reflecting on the matter, it was asserted that Edward III's renunciation of France had been imperfect. In consequence, the King of France retained his suzerainty over Aquitaine. Charles V summoned the Black Prince to answer the complaints of his vassals but Edward refused. The Caroline phase of the Hundred Years' War began.

French Recovery

Charles V resumed the war in favorable conditions. France, after all, was still the foremost kingdom in Western Europe; England had also lost its most capable military leaders — Edward III was too old, while the Black Prince was languishing in sickness.

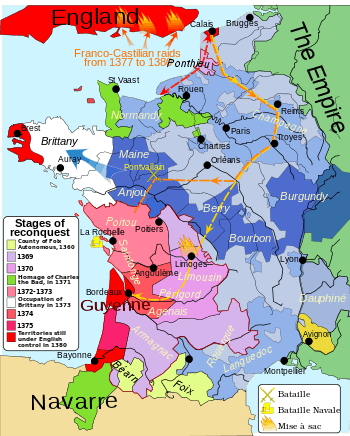

Just before New Year's Day 1370, the English seneschal of Poitou, John Chandos, was killed at the bridge at Lussac-les-Châteaux. The loss of this commander was a significant blow to the English. Jean III de Grailly, the captal de Buch, was also captured and locked up by Charles, who did not feel bound by "outdated" chivalry. Du Guesclin continued a series of careful campaigns, avoiding major English field forces, but capturing town after town, including Poitiers in 1372 and Bergerac in 1377. Du Guesclin, who according to chronicler Jean Froissart, had advised the French king not to engage the English in the field, was successful in these Fabian tactics, though in the only two major battles in which he fought, Auray (1364) and Nájera (1367), he was on the losing side and was captured but released for ransom. The English response to du Guesclin was to launch a series of destructive military expeditions, called chevauchées, in an effort at total war to destroy the countryside and the productivity of the land. But du Guesclin refused to be drawn into open battle. He continued his successful command of the French armies until his death in 1380.

In 1372, English command of the sea, which had been kept since the Battle of Sluys, came to and end by their disastrous defeat by a joint Franco-Castilian fleet at the Battle of La Rochelle in the Bay of Biscay. This defeat undermined English seaborne trade and supplies and isolated their Gascon possessions.

Treaty of Bruges

The Treaty of Bruges was a treaty signed in 1375 between France and England in Bruges, present-day Belgium. The conference leading to the treaty was called at the instigation of Pope Gregory XI.[1] France was represented in the negotiations by Philip II, Duke of Burgundy and England by John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster. Negotiations broke down over the issue of sovereignty over the Aquitaine. The English wanted full sovereignty over Edward's territories, while the French insisted that the House of Valois retain sovereignty of any Plantagenet provinces. Despite attempts by the Pope to broker a compromise, agreement could be reached and the war resumed in 1377. [2]

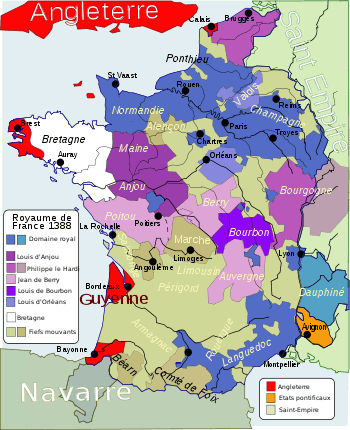

In 1376, the Black Prince died, and in April 1377, Edward III of England sent his Chancellor, Adam Houghton, to negotiate for peace with Charles, but when in June Edward himself died, Houghton was called home.[3] The underaged Richard of Bordeaux succeeded to the throne of England. It was not until Richard had been deposed by his cousin Henry Bolingbroke that the English, under the House of Lancaster, could forcefully revive their claim to the French throne. The war nonetheless continued until the first of a series of truces was signed in 1389.

Charles V died in September 1380 and was succeeded by his underage son, Charles VI, who was placed under the joint regency of his three uncles. With his successes, Charles may have believed that the end of the war was at hand. On his deathbed Charles V repealed the royal taxation necessary to fund the war effort. As the regents attempted to reimpose the taxation a popular revolt known as the Harelle broke out in Rouen. As tax collectors arrived at other French cities the revolt spread and violence broke out in Paris and most of France's other northern cities. The regency was forced to repeal the taxes to calm the situation.

John of Gaunt's Great Chevauchée

In 1373 John of Gaunt commanded what historians call the Great Chevauchée. It was launched between two epidemics of the Black Death in 1369 and 1375. The economic impact of the Black Death was devasating, and John of Gaunt was having difficulty financing his French campaign .[4] According to chronicler Jean Froissart the Chevauchée had been planned for three years. [5]

English armies were known for their devastating capability in chevauchée warfare.[6] The chevauchée or "war-ride" involved leading an army through enemy territory and burning manors, mills and villages. This wore away the enemy's tax revenues and undermined political support. Using this tactic, the English could strike and withdraw before the enemy could respond. This tactic had helped Edward III and his son, The Black Prince, force a surrender in the Edwardian Wars.[7]

The English forces were ambushed by one of France's most effective commanders, Olivier de Clisson. In the frontier lands between King Charles V's domains and the Duchy of Burgundy, 600 English and Bretons were killed and many others were taken prisoner.[8] When the English tried to cross the rivers Loire and Allier in October, they lost most of their baggage train and transport. According to the Grandes Chroniques de France the English had little provisions, and had lost many men and most of their horses. .[9] Even after the chevauchée had left Burgundian territory The Duke of Burgunday continued to watch their movements closely, and there was fierce fighting between French and English forces.

When John of Gaunt's forces finally reached Bordeaux on Christmas Eve in 1373, they were half-starved and weary. Grandes Chroniques de France says the chevauchée had lost most of their men and many knights had lost their armors because they were unable to carry them.[10] The Great Chevauchée was over.

The Great Chevauchée's defeat caused tremendous anger and resentment in Britain. John of Gaunt continued to be a powerful political player, but he was not popular and his efforts to promote peace with France were unsuccessful.[11]

The Great Schism

In 1378 Charles V's support for the election of the Avignon Pope Clement VII started the Great Schism.[12] This event split the Church for almost four decades and thwarted papal efforts to prevent or end the Hundred Years' War. The disputed papal succession resulted in several lines of popes competing for the support of national rulers, which exacerbated the political divisions of the war. Despite papal involvement in peace conferences throughout the 14th century, no settlement was ever reached, in part because the papacy was not influential enough to impose one. [13]

Bibliography

- Cannon, J. A. (2002). "Bruges, treaty of". The Oxford Companion to British History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 97-8019-86051-40.

- Nicolle, David (2011). The Great Chevauchée: John of Gaunt's Raid on France 1373. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1849082471.

- Rogers, Clifford (2006). "Chevauchée". International Encyclopedia of Military History. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415936613.

- Wagner, John A (2006). Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War. Westport CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32736-X.

- Ormrod, W., (2002). Edward III. History Today. Vol. 52(6), 20 pgs.

- Ayton, A., (1992). War and the English Gentry under Edward III. History Today. Vol. 42(3), 17 pgs.

- Harari, Y., (2000). Strategy and Supply in Fourteenth Century Western European Invasion *Campaigns. Journal of Military History. Vol. 64(2), 37 pgs.

- Saul, N., (1999). Richard II. History Today. Vol. 49(9), 5 pgs.

- Jones, W.R., (1979). The English Church and Royal Propaganda during the Hundred Years' War. The Journal of British Studies, Vol. 19(1), 12 pages.

- Perroy, E., (1951). The Hundred Years' War. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Notes

- ↑ Cannon. Treaty of Bruges 1375. The Oxford Companion to British History

- ↑ Wagner 2006, p. 63-64.

- ↑ Glanmor Williams, ‘Houghton, Adam (died 1389) ’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004), online edition, May 2008 (subscription required), accessed 4 December 2010

- ↑ Nicolle 2011, p. 4-5.

- ↑ Nicolle 2011, p. 14.

- ↑ Nicolle 2011, p. 15.

- ↑ Rogers 2006.

- ↑ Nicolle 2011, p. 58.

- ↑ Nicolle 2011, p. 59.

- ↑ Nicolle 2011, p. 68.

- ↑ Nicolle 2011, p. 76.

- ↑ Wagner 2006.

- ↑ Wagner 2006, p. 238.