Hunan

| Hunan Province 湖南省 | |

|---|---|

| Province | |

| Name transcription(s) | |

| • Chinese | 湖南省 (Húnán Shěng) |

| • Abbreviation | HN / 湘 (pinyin: Xiāng) |

.svg.png) Map showing the location of Hunan Province | |

| Coordinates: 27°24′N 111°48′E / 27.4°N 111.8°ECoordinates: 27°24′N 111°48′E / 27.4°N 111.8°E | |

| Named for |

湖 hú – lake 南 nán – south "south of the lake" |

| Capital (and largest city) | Changsha |

| Divisions | 14 prefectures, 122 counties, 2576 townships |

| Government | |

| • Secretary | Du Jiahao |

| • Governor | Xu Dazhe (acting) |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 210,000 km2 (80,000 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 10th |

| Population (2014)[2] | |

| • Total | 67,370,000 |

| • Rank | 7th |

| • Density | 320/km2 (830/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | 13th |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic composition |

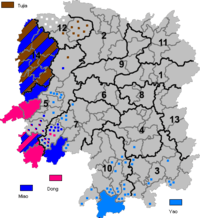

Han – 90% Tujia – 4% Miao – 3% Dong – 1% Yao – 1% Other peoples – 1% |

| • Languages and dialects |

Chinese varieties: Xiang, Gan, Southwestern Mandarin, Xiangnan Tuhua, Waxiang, Hakka. Non-Chinese languages: Xong, Tujia, Mien, Gam |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-43 |

| GDP (2016) |

CNY 3.12 trillion USD 470 billion (10th) |

| • per capita |

CNY 46,033 USD 6,932 (20th) |

| HDI (2014) | 0.735[3] (high) (20th) |

| Website |

www |

| Hunan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Hunan" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 湖南 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiang | ɣu13 nia13 (fu-lã) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "South of the Lake (Dòngtíng)" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hunan Province (Chinese: 湖南; pinyin: ![]() Húnán; Hunanese: Shuangfeng, [ɣəu˩˧læ̃˩˧]; Changsha, [fu˩˧lã˩˧]) is the 7th most populous province of China and the 10th most extensive by area. Its capital is Changsha.

Húnán; Hunanese: Shuangfeng, [ɣəu˩˧læ̃˩˧]; Changsha, [fu˩˧lã˩˧]) is the 7th most populous province of China and the 10th most extensive by area. Its capital is Changsha.

The name Hunan means "south of Lake Dongting," a lake in the northeast of the province; hu means "lake" while nan means "south."[4] Vehicle license plates from Hunan are marked Xiang (Chinese: 湘), after the Xiang River, which runs from south to north through Hunan and forms part of the largest drainage system for the province.[5]

Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed in South Central China, Hunan is a southern province, bordered to the north by Hubei Province, to the east by Jiangxi Province, to the south by Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces, to the west by Guizhou Province, and to the northwest by Chongqing.

History

Hunan's primeval forests were first occupied by the ancestors of the modern Miao, Tujia, Dong and Yao peoples. It entered the written history of China around 350 BC, when under the kings of the Zhou Dynasty, it became part of the State of Chu. After Qin conquered the Chu heartland in 278 BC, the region came under the control of Qin, and then the Han dynasty. At this time, and for hundreds of years thereafter, it was a magnet for migration of Han Chinese from the north, who displaced or assimilated the indigenous people, cleared forests and began farming rice in the valleys and plains.[6] The agricultural colonization of the lowlands was carried out in part by the Han state, which managed river dikes to protect farmland from floods.[7] To this day many of the small villages in Hunan are named after the Han families who settled there. Migration from the north was especially prevalent during the Eastern Jin Dynasty and the Southern and Northern Dynasties Periods, when nomadic invaders pushed these peoples south.

During the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period, Hunan was home to its own independent regime, Ma Chu.

Hunan and Hubei became a part of the province of Huguang (湖廣) until the Qing dynasty. Hunan province was created in 1664 from Huguang, renamed to its current name in 1723.

Hunan became an important communications center due to its position on the Yangzi River. It was an important centre of scholarly activity and Confucian thought, particularly in the Yuelu Academy in Changsha. It was also on the Imperial Highway constructed between northern and southern China. The land produced grain so abundantly that it fed many parts of China with its surpluses. The population continued to climb until, by the nineteenth century, Hunan became overcrowded and prone to peasant uprisings. Some of the uprisings, such as the ten-year Miao Rebellion of 1795–1806, were caused by ethnic tensions. The Taiping Rebellion began in the south in Guangxi Province in 1850. The rebellion spread into Hunan and then further eastward along the Yangzi River valley. Ultimately, it was a Hunanese army under Zeng Guofan who marched into Nanjing to put down the uprising in 1864.

Hunan was relatively quiet until 1910 when there were uprisings against the crumbling Qing dynasty, which were followed by the Communist's Autumn Harvest Uprising of 1927. It was led by Hunanese native Mao Zedong, and established a short-lived Hunan Soviet in 1927. The Communists maintained a guerrilla army in the mountains along the Hunan-Jiangxi border until 1934. Under pressure from the Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) forces, they began the Long March to bases in Shaanxi Province. After the departure of the Communists, the KMT army fought against the Japanese in the second Sino-Japanese war. They defended the Changsha until it fell in 1944. Japan launched Operation Ichigo, a plan to control the railroad from Wuchang to Guangzhou (Yuehan Railway). Hunan was relatively unscathed by the civil war that followed the defeat of the Japanese in 1945. In 1949, the Communists returned once more as the Nationalists retreated southward.

As Mao Zedong's home province, Hunan supported the Cultural Revolution of 1966–1976. However, it was slower than most provinces in adopting the reforms implemented by Deng Xiaoping in the years that followed Mao's death in 1976.

Former Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji is also Hunanese, as are the late President Liu Shaoqi and the late Marshal Peng Dehuai.

Geography

Hunan is located on the south bank of the Yangtze River, about half way along its length, situated between 108° 47'–114° 16' east longitude and 24° 37'–30° 08' north latitude. It covers an area of 211,800 square kilometres (81,800 square miles), making it the 10th largest provincial-level division. The east, south and west sides of the province are surrounded by mountains and hills, such as the Wuling Mountains to the northwest, the Xuefeng Mountains to the west, the Nanling Mountains to the south, and the Luoxiao Mountains to the east. The mountains and hills occupy more than 80% of the area and plains comprises less than 20% of the whole province.

The Xiang, the Zi, the Yuan and the Lishui Rivers converge on the Yangtze River at Lake Dongting in the north of Hunan. The center and northern parts are somewhat low and a U-shaped basin, open in the north and with Lake Dongting as its center. Most of Hunan lies in the basins of four major tributaries of the Yangtze River.

Lake Dongting is the largest lake in the province and the second largest freshwater lake of China.

The Xiaoxiang area and Lake Dongting figure prominently in Chinese poetry and paintings, particularly during the Song Dynasty when they were associated with officials who had been unjustly dismissed.[8]

Changsha (which means "long sands") was an active ceramics district during the Tang Dynasty, its tea bowls, ewers and other products mass-produced and shipped to China's coastal cities for export abroad. An Arab dhow dated to the 830s and today known as the Belitung Shipwreck was discovered off the small island of Belitung, Indonesia with more than 60,000 pieces in its cargo. The salvaged cargo is today housed in nearby Singapore.

Hunan's climate is subtropical, and, under the Köppen climate classification, is classified as being humid subtropical (Köppen Cfa), with short, cool, damp winters, very hot and humid summers, and plenty of rainfall. January temperatures average 3 to 8 °C (37 to 46 °F) while July temperatures average around 27 to 30 °C (81 to 86 °F). Average annual precipitation is 1,200 to 1,700 millimetres (47 to 67 in).

The Furongian Epoch in the Cambrian Period of geological time is named for Hunan. (Furong (芙蓉) means "lotus" in Mandarin and refers to Hunan which is known as the "lotus state").[9]

Administrative divisions

Hunan is divided into fourteen prefecture-level divisions: thirteen prefecture-level cities and an autonomous prefecture:

| Administrative divisions of Hunan | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| № | Division code[10] | English name | Chinese | Pinyin | Area in km2[11] | Population 2010[12] | Seat | Divisions[13] | |||

| Districts | Counties | Aut. counties | CL cities | ||||||||

| 430000 | Hunan | 湖南省 | Húnán Shěng | 210000.00 | 65,683,722 | Changsha | 35 | 64 | 7 | 16 | |

| 1 | 430100 | Changsha | 长沙市 | Chángshā Shì | 11,819.46 | 7,044,118 | Yuelu District | 6 | 2 | 1 | |

| 13 | 430200 | Zhuzhou | 株洲市 | Zhūzhōu Shì | 11,262.20 | 3,855,609 | Tianyuan District | 4 | 4 | 1 | |

| 8 | 430300 | Xiangtan | 湘潭市 | Xiāngtán Shì | 5,006.46 | 2,748,552 | Yuetang District | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| 4 | 430400 | Hengyang | 衡阳市 | Héngyáng Shì | 15,302.78 | 7,141,462 | Zhengxiang District | 5 | 5 | 2 | |

| 7 | 430500 | Shaoyang | 邵阳市 | Shàoyáng Shì | 20,829.63 | 7,071,826 | Daxiang District | 3 | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | 430600 | Yueyang | 岳阳市 | Yuèyáng Shì | 14,897.88 | 5,477,911 | Yueyanglou District | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| 2 | 430700 | Changde | 常德市 | Chángdé Shì | 18,177.18 | 5,747,218 | Wuling District | 2 | 6 | 1 | |

| 12 | 430800 | Zhangjiajie | 张家界市 | Zhāngjiājiè Shì | 9,516.03 | 1,476,521 | Yongding District | 2 | 2 | ||

| 9 | 430900 | Yiyang | 益阳市 | Yìyáng Shì | 12,325.16 | 4,313,084 | Heshan District | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| 3 | 431000 | Chenzhou | 郴州市 | Chēnzhōu Shì | 19,317.33 | 4,581,778 | Beihu District | 2 | 8 | 1 | |

| 10 | 431100 | Yongzhou | 永州市 | Yǒngzhōu Shì | 22,255.31 | 5,180,235 | Lengshuitan District | 2 | 8 | 1 | |

| 5 | 431200 | Huaihua | 怀化市 | Huáihuà Shì | 27,562.72 | 4,741,948 | Hecheng District | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| 6 | 431300 | Loudi | 娄底市 | Lóudǐ Shì | 8,107.61 | 3,785,627 | Louxing District | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| 14 | 433100 | Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture |

湘西土家族苗族自治州 | Xiāngxī Tǔjiāzú Miáozú Zìzhìzhōu | 15,462.30 | 2,547,833 | Jishou | 7 | 1 | ||

The fourteen prefecture-level divisions of Hunan are subdivided into 122 county-level divisions (35 districts, 16 county-level cities, 64 counties, 7 autonomous counties). Those are in turn divided into 2587 township-level divisions (1098 towns, 1158 townships, 98 ethnic townships, 225 subdistricts, and eight district public offices).

Politics

The politics of Hunan is structured in a dual party-government system like all other governing institutions in mainland China.

The Governor of Hunan is the highest-ranking official in the People's Government of Hunan. However, in the province's dual party-government governing system, the Governor has less power than the Hunan Communist Party of China Provincial Committee Secretary, colloquially termed the "Hunan CPC Party Chief".

Economy

As of the mid 19th century, Hunan exported rhubarb, musk, honey, tobacco, hemp, and birds.[14] The Lake Dongting area is an important center of ramie production, and Hunan is also an important center of tea cultivation. Aside from agricultural products, in recent years Hunan has grown to become an important center for steel, machinery and electronics production, especially as China's manufacturing sector moves away from coastal provinces such as Guangdong and Zhejiang.[15]

The Lengshuijiang area is noted for its stibnite mines, and is one of the major centers of antimony extraction in China.

Hunan is also well known for a few international makers of construction equipments such as concrete pumps, cranes, etc. These companies include Sany Group, Zoomlion and Sunward. Sany is one of the major players in the world. Liuyang is the major maker of fireworks in the world. [16] [17]

Its nominal GDP for 2011 was 1.90 trillion yuan (US$300 billion). Its per capita GDP was 20,226 yuan (US$2,961).[18]

Economic and technological development zones

- Changsha National Economic and Technical Development Zone

The Changsha National Economic and Technology Development Zone was founded in 1992. It is located east of Changsha. The total planned area is 38.6 km2 (14.9 sq mi) and the current area is 14 km2 (5.4 sq mi). Near the zone is National Highways G319 and G107 as well as Jingzhu Highway. Besides that, it is very close to the downtown and the railway station. The distance between the zone and the airport is 8 km (5.0 mi). The major industries in the zone include high-tech industry, biology project technology and new material industry.[19]

- Changsha National New & Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone

- Chenzhou Export Processing Zone

Approved by the State Council, Chenzhou Export processing Zone (CEPZ) was established in 2005 and is the only export processing zone in Hunan province. The scheduled production area of CEPZ covers 3km2. The industrial positioning of CEPZ is to concentrate on developing export-oriented hi-tech industries, including electronic information, precision machinery, and new-type materials. The zone has good infrastructure, and the enterprises inside could enjoy the preferential policies of tax-exemption, tax-guarantee and tax-refunding. By the end of the “Eleventh Five-Year Plan”, the CEPZ achieved a total export and import volume of over US$1 billion and provided more than 50,000 jobs. It aimed to be one of the first-class export processing zones in China.[20]

- Zhuzhou National New & Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone

Zhuzhou Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone was founded in 1992. Its total planned area is 35 km2 (14 sq mi). It is very close to National Highway G320. The major industries in the zone include biotechnology, food processing and heavy industry. In 2007, the park signed a cooperation contract with Beijing Automobile Industry, one of the largest auto makers in China, which will set up a manufacturing base in Zhuzhou HTP.[21]

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1912[22] | 27,617,000 | — |

| 1928[23] | 31,501,000 | +14.1% |

| 1936-37[24] | 28,294,000 | −10.2% |

| 1947[25] | 25,558,000 | −9.7% |

| 1954[26] | 33,226,954 | +30.0% |

| 1964[27] | 37,182,286 | +11.9% |

| 1982[28] | 54,008,851 | +45.3% |

| 1990[29] | 60,659,754 | +12.3% |

| 2000[30] | 63,274,173 | +4.3% |

| 2010[31] | 65,683,722 | +3.8% |

As of the 2000 census, the population of Hunan is 64,400,700 consisting of forty-one ethnic groups. Its population grew 6.17% (3,742,700) from its 1990 levels. According to the census, 89.79% (57,540,000) identified themselves as Han people, 10.21% (6,575,300) as minority groups. The minority groups are Tujia, Miao, Dong, Yao, Bai, Hui, Zhuang, Uyghurs and so on.

In Hunan, ethnic minority languages are spoken in the following prefectures.

- Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture: Qo Xiong language, Tujia language

- Huaihua: Qo Xiong language, Dong language, Hm Nai language, Hmu language

- Shaoyang: Maojia language, Hm Nai language, Pa-Hng language

- Yongzhou: Mien language, Biao Min language

- Chenzhou: Dzao Min language

Hunanese Uyghurs

Around 5,000 Uyghurs live around Taoyuan County and other parts of Changde.[33][34][35][36] Hui and Uyghurs have intermarried in this area.[37][38][39] In addition to eating pork, the Uygurs of Changde practice other Han Chinese customs, like ancestor worship at graves. Some Uyghurs from Xinjiang visit the Hunan Uyghurs out of curiosity or interest.[40] Also, the Uyghurs of Hunan do not speak the Uyghur language, instead, they speak Chinese as their native language.[41]

Religion

The predominant religions in Hunan are Chinese folk religions, Taoist traditions and Chinese Buddhism. According to surveys conducted in 2007 and 2009, 20.19% of the population believes and is involved in ancestor veneration, while 0.77% of the population identifies as Christian.[32] The reports didn't give figures for other types of religion; 79.04% of the population may be either irreligious or involved in worship of nature deities, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, folk religious sects.

|

Culture

Xiang Chinese (湘語) is the biggest native language to Hunan province, and it is also a group of Chinese dialects spoken in most parts of Hunan and in a few adjacent areas.

Hunanese cuisine is noted for its use of chili peppers.

Huaguxi is a local form of Chinese opera that is very popular in Hunan province.

Nü shu is a writing system that was used exclusively among women in Jiangyong County.

Hunan's culture industry generated 87 billion yuan (US$11.76 billion) in economic value in 2007,[42] a major contributor to the province's economic growth. The industry accounts for 7.5 percent of the region's GDP - 0.9 percentage points higher than the previous year.

Tourism

Located in the south central part of the Chinese mainland, Hunan has long been known for its natural beauty. It is surrounded by mountains on the east, west, and south, and by the Yangtze River on the north. Its mixture of mountains and water makes it among the most beautiful provinces in China. For thousands of years, the region has been a major center of agriculture, growing rice, tea, and oranges. China's first all glass suspension bridge was also opened in Hunan, in Shiniuzhai National Geological Park.[43]

- Shaoshan, the village where Mao Zedong was born

- Wulingyuan Scenic and Historic Interest Area (World Heritage Site)

- Yueyang Tower in Yueyang

- Mount Heng in Hengyang

- Zhangjiajie

- Fenghuang County in Xiangxi Prefecture

- Hong Jiang

Education

See List of universities and colleges in Hunan

Sports

Professional sports teams in Hunan include:

See also

- Major national historical and cultural sites in Hunan

- Xiaoxiang, the "lakes and rivers" region of south-central China

- State of Chu, ancient Chinese state partly in modern-day Hunan

Notes

- ↑ The data was collected by the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) of 2009 and by the Chinese Spiritual Life Survey (CSLS) of 2007, reported and assembled by Xiuhua Wang (2015)[32] in order to confront the proportion of people identifying with two similar social structures: ① Christian churches, and ② the traditional Chinese religion of the lineage (i. e. people believing and worshipping ancestral deities often organised into lineage "churches" and ancestral shrines). Data for other religions with a significant presence in China (deity cults, Buddhism, Taoism, folk religious sects, Islam, et. al.) was not reported by Wang.

- ↑ This may include:

- Buddhists;

- Confucians;

- Deity worshippers;

- Taoists;

- Members of folk religious sects;

- Small minorities of Muslims;

- And people not bounded to, nor practicing any, institutional or diffuse religion.

Notes

- ↑ "Doing Business in China – Survey". Ministry Of Commerce – People's Republic Of China. Archived from the original on 5 August 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ "National Data: Annual by Province". National Bureau of Statistics of China. 29 April 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ↑ List of administrative divisions of Greater China by Human Development Index

- ↑ (in Chinese) Origin of the Names of China's Provinces, People's Daily Online.

- ↑ 湖南被誉为三湘四水的由来

- ↑ Harold Wiens. Han Expansion in South China. (Shoe String Press, 1967).

- ↑ Brian Lander. State Management of River Dikes in Early China: New Sources on the Environmental History of the Central Yangzi Region . T'oung Pao 100.4-5 (2014): 325–362

- ↑ Alfreda Murck (2000). Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent. Harvard Univ Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-00782-6.

- ↑ Peng, Shanchi; Babcock, Loren; Robison, Richard; Lin, Huanling; Rees, Margaret; Saltzman, Matthew (30 November 2004). "Global Standard Stratotype-section and Point (GSSP) of the Furongian Series and Paibian Stage (Cambrian)" (PDF). Lethaia. 37 (4): 365–379. doi:10.1080/00241160410002081. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ↑ "中华人民共和国县以上行政区划代码". 中华人民共和国民政部.

- ↑ 深圳市统计局. 《深圳统计年鉴2014》. 深圳统计网. 中国统计出版社. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

- ↑ shi, Guo wu yuan ren kou pu cha ban gong; council, Guo jia tong ji ju ren kou he jiu ye tong ji si bian = Tabulation on the 2010 population census of the people's republic of China by township / compiled by Population census office under the state; population, Department of; statistics, employment statistics national bureau of (2012). Zhongguo 2010 nian ren kou pu cha fen xiang, zhen, jie dao zi liao (Di 1 ban. ed.). Beijing Shi: Zhongguo tong ji chu ban she. ISBN 978-7-5037-6660-2.

- ↑ 中华人民共和国民政部 (August 2014). 《中国民政统计年鉴2014》. 中国统计出版社. ISBN 978-7-5037-7130-9.

- ↑ Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 123.

- ↑ http://www.thechinaperspective.com/topics/province/hunan-province/

- ↑ http://www.enghunan.gov.cn/

- ↑ http://www.baike.com/wiki/%E6%B9%96%E5%8D%97%E7%9C%81

- ↑ http://www.stats.gov.cn/was40/gjtjj_detail.jsp?channelid=4362&record=14

- ↑ RightSite.asia | Changsha National Economic and Technology Development Zone

- ↑ RightSite.asia | Chenzhou Export Processing Zone

- ↑ RightSite.asia | Zhuzhou Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone

- ↑ "1912年中国人口". Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "1928年中国人口". Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "1936-37年中国人口". Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "1947年全国人口". Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "中华人民共和国国家统计局关于第一次全国人口调查登记结果的公报". National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on August 5, 2009.

- ↑ "第二次全国人口普查结果的几项主要统计数字". National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012.

- ↑ "中华人民共和国国家统计局关于一九八二年人口普查主要数字的公报". National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012.

- ↑ "中华人民共和国国家统计局关于一九九〇年人口普查主要数据的公报". National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on June 19, 2012.

- ↑ "现将2000年第五次全国人口普查快速汇总的人口地区分布数据公布如下". National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Communiqué of the National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China on Major Figures of the 2010 Population Census". National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on July 27, 2013.

- 1 2 3 China General Social Survey 2009, Chinese Spiritual Life Survey (CSLS) 2007. Report by: Xiuhua Wang (2015, p. 15) Archived September 25, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ stin Jon Rudelson, Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson (1992). Bones in the sand: the struggle to create Uighur nationalist ideologies in Xinjiang, China. Harvard University. p. 30. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Ingvar Svanberg (1988). The Altaic-speakers of China: numbers and distribution. Centre for Mult[i]ethnic Research, Uppsala University, Faculty of Arts. p. 7. ISBN 91-86624-20-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Ingvar Svanberg (1988). The Altaic-speakers of China: numbers and distribution. Centre for Mult[i]ethnic Research, Uppsala University, Faculty of Arts. p. 7. ISBN 91-86624-20-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Kathryn M. Coughlin (2006). Muslim cultures today: a reference guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 220. ISBN 0-313-32386-0. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press,. p. 133. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press,. p. 137. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press,. p. 138. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press,. p. 136. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Chih-yu Shih, Zhiyu Shi (2002). Negotiating ethnicity in China: citizenship as a response to the state. Psychology Press,. p. 133. ISBN 0-415-28372-8. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ according to Hunan Provincial Bureau of Statistics

- ↑ "China's first glass-bottom bridge opens - CNN.com". CNN. Retrieved 2015-09-29.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hunan. |

Hunan travel guide from Wikivoyage

Hunan travel guide from Wikivoyage- Hunan Government website

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hu-nan". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hu-nan". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

.svg.png)