Humerus fracture

| Humerus fracture | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Comminuted midshaft humerus fracture with callus formation | |

| ICD-10 | S42.2-S42.4 |

| AO | 11A1-13C3 |

| eMedicine | 1239985, 1261320 |

| MeSH | 68006810 |

A humerus fracture is a bone fracture of the bone of the upper arm, the humerus. Fractures of the humerus may be classified by the location of the fracture and divided into fractures of the proximal region, which is near the shoulder, the middle region, which is the shaft of the humerus, and the distal region, which is near the elbow. These locations can further be divided based on the extent of the fracture and the specific areas of each of the three regions affected. Humerus fractures usually occur after physical trauma, falls, excess physical stress, or pathological conditions. Falls are the most common cause of proximal and shaft fractures, and those who experience a fracture from a fall usually have an underlying risk factor for bone fracture. Distal fractures occur most frequently in children who experience physical trauma to the elbow area.

Symptoms of fracture are pain, swelling, and discoloration of the skin at the site of the fracture. Bruising appears a few days after the fracture. The neurovascular bundle of the arm may be affected in severe cases, which will cause loss of nerve function and diminished blood supply beneath the fracture. Proximal and distal fractures will often cause a loss of shoulder or elbow function. Displaced shaft and distal fractures may cause deformity, and such shaft fractures will often shorten the length of the upper arm. Most humerus fractures are nondisplaced and will heal within a few weeks if the arm is immobilized. Severe displaced humerus fractures and complications often require surgical intervention. In most cases, normal function to the arm returns after the fracture is healed. In severe cases, however, function of the arm may be diminished after recovery.

Classification

Fractures of the humerus are classified based on the location of the fracture and then by the type of fracture. There are three locations that humerus fractures occur: at the proximal location, which is the top of the humerus near the shoulder, in the middle, which is at the shaft of the humerus, and the distal location, which is the bottom of the humerus near the elbow.[1] Proximal fractures are classified into one of four types of fractures based on the displacement of the greater tubercle, the lesser tubercle, the surgical neck, and the anatomical neck, which are the four parts of the proximal humerus, with fracture displacement being defined as at least one centimeter of separation or an angulation greater than 45 degrees. One-part fractures involve no displacement of any parts of the humerus, two-part fractures have one part displaced relative to the other three; three-part fractures have two displaced fragments, and four-part fractures have all fragments displaced from each other.[2][3][4] Fractures of the humerus shaft are subdivided into transverse fractures, spiral fractures, "butterfly" fractures, which are a combination of transverse and spiral fractures, and pathological fractures, which are fractures caused by medical conditions.[5] Distal fractures are split between supracondylar fractures, which are transverse fractures above the two condyles at the bottom of the humerus, and intercondylar fractures, which involve a T- or Y-shaped fracture that splits the condyles.[6]

Causes

Humerus fractures usually occur after physical trauma, falls, excess physical stress, or pathological conditions. Proximal humerus fractures most often occur among elderly patients with osteoporosis who fall on an outstretched arm.[1] Less frequently, proximal fractures occur from motor vehicle accidents, gunshots, and violent muscle contractions from an electric shock or seizure.[7][8] Other risk factors for proximal fractures include having a low bone mineral density, having impaired vision and balance, and tobacco smoking.[9] A stress fracture of the proximal and shaft regions can occur after an excessive amount of throwing, such as pitching in baseball.[10] Middle fractures are usually caused by either physical trauma or falls. Physical trauma to the humerus shaft tends to produce transverse fractures whereas falls tend to produce spiral fractures. Metastatic breast cancer may also cause fractures in the humerus shaft.[5] Long spiral fractures of the shaft that are present in children may indicate physical abuse.[8] Distal fractures usually occur as a result of physical trauma to the elbow region. If the elbow is bent during the trauma, then the olecranon is driven upward, producing a T- or Y-shaped fracture or displacing one of the condyles.[6] Falls that produce humerus fractures among the elderly are usually accompanied by a preexisting risk factor for bone fracture, such as osteoporosis, a low bone density, or vitamin B deficiency.[11]

Symptoms

After a humerus fracture, pain is immediate, enduring, and exacerbated with the slightest movements. The affected region swells, with bruising appearing a day or two after the fracture. The fracture is typically accompanied by a discoloration of the skin at the site of the fracture.[4][12] A crackling or rattling sound may also be present, caused by the fractured humerus pressing against itself.[8] In cases in which the nerves are affected, then there will be a loss of control or sensation in the arm below the fracture.[10][12] If the fracture affects the blood supply, then the patient will have a diminished pulse at the wrist.[10] Displaced fractures of the humerus shaft will often cause deformity and a shortening of the length of the upper arm.[8] Distal fractures may also cause deformity, and they typically limit the ability to flex the elbow.[6]

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of humerus fractures is typically made through radiographic imaging. For proximal fractures, X-rays can be taken from a scapular anteroposterior (AP) view, which takes an image of the front of the shoulder region from an angle, a scapular Y view, which takes an image of the back of the shoulder region from an angle, and an axillar lateral view, which has the patient lie on his or her back, lift the bottom half of the arm up to the side, and have an image taken of the axilla region underneath the shoulder.[1] Fractures of the humerus shaft are usually correctly identified with radiographic images taken from the AP and lateral viewpoints.[5] Damage to the radial nerve from a shaft fracture can be identified by an inability to bend the hand backwards or by decreased sensation in the back of the hand.[8] Images of the distal region are often of poor quality due to the patient being unable to extend the elbow because of pain. If a severe distal fracture is supected, then a computed tomography (CT) scan can provide greater detail of the fracture. Nondisplaced distal fractures may not be directly visible; they may only be visible due to fat being displaced because of internal bleeding in the elbow.[6]

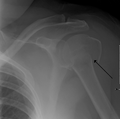

A fracture of the greater tubercle as seen on AP X ray

A fracture of the greater tubercle as seen on AP X ray A fracture of the greater tubercle of the humerus

A fracture of the greater tubercle of the humerus Fracture of the greater tubercle of the humerus

Fracture of the greater tubercle of the humerus Fracture of the proximal humerus with involvement of the greater tubercle

Fracture of the proximal humerus with involvement of the greater tubercle Proximal humerus fracture

Proximal humerus fracture A transverse fracture of the humerus shaft

A transverse fracture of the humerus shaft A spiral fracture of the humerus shaft

A spiral fracture of the humerus shaft- A displaced supracondylar fracture

Treatment

The aim of treatment is to minimize pain and to restore as much normal function as possible. Most humerus fractures do not require surgical intervention.[12] One-part and two-part proximal fractures can be treated with a collar and cuff sling, adequate pain medicine, and follow up therapy. Two-part proximal fractures may require open or closed reduction depending on neurovascular injury, rotator cuff injury, dislocation, likelihood of union, and function. For three- and four-part proximal fractures, standard practice is to have open reduction and internal fixation to realign the separate parts of the proximal humerus. A humeral hemiarthroplasty may be required in proximal cases in which the blood supply to the region is compromised.[13] Fractures of the humerus shaft and distal part of the humerus are most often uncomplicated, closed fractures that require nothing more than pain medicine and wearing a cast or sling for a few weeks. In shaft and distal cases in which complications such as damage to the neurovascular bundle exist, then surgical repair is required.[14]

Prognosis

In most cases, patients are discharged from an emergency department with pain medicine and a cast or sling. These fractures are typically minor and heal naturally over the course of a few weeks.[12] Fractures of the proximal region, especially among elderly patients, may limit future shoulder activity.[15][16] Severe fractures are usually resolved with surgical intervention, followed by a period of healing using a cast or sling.[9] Severe fractures often cause long-term loss of physical ability.[17] Complications in the recovery process of severe fractures include osteonecrosis, malunion or nonunion of the fracture, stiffness, and rotator cuff dysfunction, which require additional intervention in order for the patient to fully recover.[17]

Epidemiology

Humerus fractures are among the most common of fractures. Proximal fractures make up 5% of all fractures and 25% of humerus fractures,[1] middle fractures about 60% of humerus fractures (12% of all fractures),[5] and distal fractures the remainder. Among proximal fractures, 80% are one-part, 10% are two-part, and the remaining 10% are three- and four-part.[18] The most common location of proximal fractures is at the surgical neck of the humerus.[4] Incidence of proximal fractures increases with age, with about 75% of cases occurring among people over the age of 60.[9] In this age group, about three times as many women than men experience a proximal fracture.[19] Middle fractures are also common among the elderly, but they frequently occur among physically active young adult men who experience physical trauma to the humerus.[5] Distal fractures are rare among adults, occurring primarily in children who experience physical trauma to the elbow region.[6]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 167

- ↑ Cameron, et al., 2014, pp. 167–168

- ↑ Crosby, et al., 2014, pp. 11–19

- 1 2 3 Cuccurullo, 2014, p. 177

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 169

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 170

- ↑ Crosby, et al., 2014, p. 4

- 1 2 3 4 5 Auth, 2012, p. 167

- 1 2 3 Crosby, et al., 2014, p. 23

- 1 2 3 Cuccurullo, 2014, p. 178

- ↑ Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 167, 169

- 1 2 3 4 Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 167–170

- ↑ Cameron, et al., 2014, pp. 168–169

- ↑ Cameron, et al., 2014, pp. 169–170

- ↑ Malhotra, 2013, p. 47

- ↑ Crosby, et al., 2014, p. 31

- 1 2 Crosby, et al., 2014, p. 35

- ↑ Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 168

- ↑ Crosby, et al., 2014, p. 1

Bibliography

- Auth, P. C. (30 July 2012). Physician Assistant Review. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 167. ISBN 9781451171297. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Malhotra, R. (15 December 2013). Mastering Orthopedic Techniques: Intra-articular Fractures. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 47–62. ISBN 9789350908266. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Cameron, P.; Jelinek, G.; Kelly, A. M.; Brown, A. F. T.; Little, M. (1 April 2014). Textbook of Adult Emergency Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 167–170. ISBN 9780702054389. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Crosby, L.; Neviaser, R. (28 October 2014). Proximal Humerus Fractures: Evaluation and Management. Springer. ISBN 9783319089515. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Cuccurullo, S. J. (25 November 2014). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Board Review, Third Edition. Demos Medical Publishing. p. 177–178. ISBN 9781617052019. Retrieved 25 August 2016.