Human population planning

|

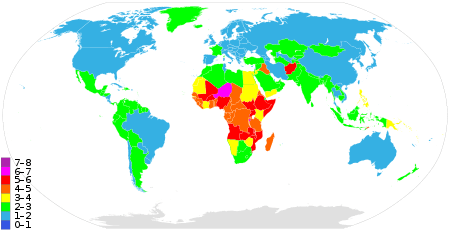

7-8 children

6-7 children

5-6 children

4-5 children

|

3-4 children

2-3 children

1-2 children

0-1 children

|

Human population planning is the practice of intentionally managing the rate of growth of a human population. Historically human population planning has been implemented with the goal of increasing the rate of human population growth. However, in the period from the 1950s to the 1980s, concerns about global population growth and its effects on poverty, environmental degradation and political stability led to efforts to reduce human population growth rates. More recently, some countries, such as Iran and Spain, have begun efforts to increase their birth rates once again.

While population planning can involve measures that improve people's lives by giving them greater control of their reproduction, a few programs, most notably the Chinese government's "one-child policy", have resorted to coercive measures.

Types

Four types of population planning goals pursued by governments can be identified:

- Increasing the overall population growth rate

- Reducing the overall population growth rate

- Decreasing the relative population growth of a less favoured subgroup of a national population or ethnic group, such as people of low intelligence or people with disabilities. This is known as eugenics.

- Instead of trying to control the rate of population growth per se, trying to arrange things so that all population groups of a certain type (e.g. all social classes within a society) have the same average rate of population growth. This is not eugenics, because it does not discriminate, but it is an attempt to avoid a dysgenic outcome.

Methods

While a specific population planning practice may be legal/mandated in one country, it may be illegal or restricted in another, indicative of the controversy surrounding this topic.

Reducing population growth

Population planning that is intended to reduce a population or sub-population's growth rates may promote or enforce one or more of the following practices, although there are other methods as well:

- Higher taxation of parents who have "excess" children

- Contraception

- Abstinence

- Reducing infant mortality so that parents do not need to have many children to ensure at least some survive to adulthood.[1]

- Abortion

- Changing status of women causing departure from traditional sexual division of labour.

- Sterilization

- One-child and Two-child policies, and other policies restricting or discouraging births directly.

- Family planning[2]

- Create small family "role models"[2]

- Tighter immigration restrictions

The method(s) chosen can be strongly influenced by the religious and cultural beliefs of community members. The failure of other methods of population planning can lead to the use of abortion or infanticide as solutions.

Increasing population growth

Population policies that are intended to increase a population or sub-population's growth rates may use practices such as:

- Higher taxation of married couples who have no, or too few, children

- Politicians imploring the populace to have bigger families

- Tax breaks and subsidies for families with children

- Loosening of immigration restrictions, and/or mass recruitment of foreign workers by the government

History

Ancient times through Middle Ages

A number of ancient writers have reflected on the issue of population. At about 300 BC, the Indian political philosopher Chanakya (c. 350-283 BC) considered population a source of political, economic, and military strength. Though a given region can house too many or too few people, he considered the latter possibility to be the greater evil. Chanakya favored the remarriage of widows (which at the time was forbidden in India), opposed taxes encouraging emigration, and believed in restricting asceticism to the aged.[3]

In ancient Greece, Plato (427-347 BC) and Aristotle (384-322 BC) discussed the best population size for Greek city-states such as Sparta, and concluded that cities should be small enough for efficient administration and direct citizen participation in public affairs, but at the same time needed to be large enough to defend themselves against hostile neighbors. In order to maintain a desired population size, the philosophers advised that procreation, and if necessary, immigration, should be encouraged if the population size was too small. Emigration to colonies would be encouraged should the population become too large.[4] Aristotle concluded that a large increase in population would bring, "certain poverty on the citizenry, and poverty is the cause of sedition and evil." To halt rapid population increase, Aristotle advocated the use of abortion and the exposure of newborns (that is, infanticide).[5]

Confucius (551-478 BC) and other Chinese writers cautioned that, "excessive growth may reduce output per worker, repress levels of living for the masses and engender strife." Confucius also observed that, "mortality increases when food supply is insufficient; that premature marriage makes for high infantile mortality rates, that war checks population growth."[4]

Ancient Rome, especially in the time of Augustus (63 BC- AD 14), needed manpower to acquire and administer the vast Roman Empire. A series of laws were instituted to encourage early marriage and frequent childbirth. Lex Julia (18 BC) and the Lex Papia Poppaea (AD 9) are two well known examples of such laws, which among others, provided tax breaks and preferential treatment when applying for public office for those that complied with the laws. Severe limitations were imposed on those who did not. For example, the surviving spouse of a childless couple could only inherit one-tenth of the deceased fortune, while the rest was taken by the state. These laws encountered resistance from the population which led to the disregard of their provisions and to their eventual abolition.[3]

Tertullian, an early Christian author (ca. AD 160-220), was one of the first to describe famine and war as factors that can prevent overpopulation.[3] He wrote: "The strongest witness is the vast population of the earth to which we are a burden and she scarcely can provide for our needs; as our demands grow greater, our complaints against Nature's inadequacy are heard by all. The scourges of pestilence, famine, wars and earthquakes have come to be regarded as a blessing to overcrowded nations, since they serve to prune away the luxuriant growth of the human race."[6]

Ibn Khaldun, a North African Arab polymath (1332–1406), considered population changes to be connected to economic development, linking high birth rates and low death rates to times of economic upswing, and low birth rates and high death rates to economic downswing. Khaldoun concluded that high population density rather than high absolute population numbers were desirable to achieve more efficient division of labour and cheap administration.[6]

During the Middle Ages in Christian Europe, population issues were rarely discussed in isolation. Attitudes were generally pro-natalist in line with the Biblical command, "Be ye fruitful and multiply."[6]

16th and 17th centuries

European cities grew more rapidly than before, and throughout the 16th century and early 17th century discussions on the advantages and disadvantages of population growth were frequent.[7] Niccolò Machiavelli, an Italian Renaissance political philosopher, wrote, "When every province of the world so teems with inhabitants that they can neither subsist where they are nor remove themselves elsewhere... the world will purge itself in one or another of these three ways," listing floods, plague and famine.[8] Martin Luther concluded, "God makes children. He is also going to feed them."[8]

Jean Bodin, a French jurist and political philosopher (1530–1596), argued that larger populations meant more production and more exports, increasing the wealth of a country.[8] Giovanni Botero, an Italian priest and diplomat (1540–1617), emphasized that, "the greatness of a city rests on the multitude of its inhabitants and their power," but pointed out that a population cannot increase beyond its food supply. If this limit was approached, late marriage, emigration, and war would serve to restore the balance.[8]

Richard Hakluyt, an English writer (1527–1616), observed that, "Throughe our longe peace and seldome sickness... wee are growen more populous than ever heretofore;... many thousandes of idle persons are within this realme, which, havinge no way to be sett on worke, be either mutinous and seeke alteration in the state, or at leaste very burdensome to the commonwealthe." Hakluyt believed that this led to crime and full jails and in A Discourse on Western Planting (1584), Hakluyt advocated for the emigration of the surplus population.[7] With the onset of the Thirty Years' War (1618–48), characterized by widespread devastation and deaths brought on by hunger and disease in Europe, concerns about depopulation returned.[9]

Population planning movement

In the 20th century, population planning proponents have drawn from the insights of Thomas Malthus, a British clergyman and economist who published An Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798. Malthus argued that, "Population, when unchecked, increases in a geometrical ratio. Subsistence increases only in an arithmetical ratio." He also outlined the idea of "positive checks" and "preventative checks." "Positive checks", such as diseases, war, disaster, famine, and genocide are factors that Malthus considered to increase the death rate.[10] "Preventative checks" were factors that Malthus believed to affect the birth rate such as moral restraint, abstinence and birth control.[10] He predicted that "positive checks" on exponential population growth would ultimately save humanity from itself and that human misery was an "absolute necessary consequence."[11] Malthus went on to explain why he believed that this misery affected the poor in a disproportionate manner.

There is a constant effort towards an increase in population which tends to subject the lower classes of society to distress and to prevent any great permanent amelioration of their condition…. The way in which these effects are produced seems to be this. We will suppose the means of subsistence in any country just equal to the easy support of its inhabitants. The constant effort towards population... increases the number of people before the means of subsistence are increased. The food, therefore which before supplied seven millions must now be divided among seven millions and half or eight millions. The poor consequently must live much worse, and many of them be reduced to severe distress.[12]

Finally, Malthus advocated for the education of the lower class about the use of "moral restraint" or voluntary abstinence, which he believed would slow the growth rate.[13]

Paul R. Ehrlich, a US biologist and environmentalist, published The Population Bomb in 1968, advocating stringent population planning policies.[14] His central argument on population is as follows:

A cancer is an uncontrolled multiplication of cells; the population explosion is an uncontrolled multiplication of people. Treating only the symptoms of cancer may make the victim more comfortable at first, but eventually he dies - often horribly. A similar fate awaits a world with a population explosion if only the symptoms are treated. We must shift our efforts from treatment of the symptoms to the cutting out of the cancer. The operation will demand many apparent brutal and heartless decisions. The pain may be intense. But the disease is so far advanced that only with radical surgery does the patient have a chance to survive.— [15]

In his concluding chapter, Ehrlich offered a partial solution to the "population problem," "[We need] compulsory birth regulation... [through] the addition of temporary sterilants to water supplies or staple food. Doses of the antidote would be carefully rationed by the government to produce the desired family size".[15]

Ehrlich's views came to be accepted by many population planning advocates in the United States and Europe in the 1960s and 1970s.[16] Since Ehrlich introduced his idea of the "population bomb," overpopulation has been blamed for a variety of issues, including increasing poverty, high unemployment rates, environmental degradation, famine and genocide.[11] In a 2004 interview, Ehrlich reviewed the predictions in his book and found that while the specific dates within his predictions may have been wrong, his predictions about climate change and disease were valid. Ehrlich continued to advocate for population planning and co-authored the book The Population Explosion, released in 1990 with his wife Anne Ehrlich.

However, it is controversial as to whether human population stabilization will avert environmental risks.[17][18][19]

Paige Whaley Eager argues that the shift in perception that occurred in the 1960s must be understood in the context of the demographic changes that took place at the time.[20] It was only in the first decade of the 19th century that the world's population reached one billion. The second billion was added in the 1930s, and the next billion in the 1960s. 90 percent of this net increase occurred in developing countries.[20] Eager also argues that, at the time, the United States recognised that these demographic changes could significantly affect global geopolitics. Large increases occurred in China, Mexico and Nigeria, and demographers warned of a "population explosion," particularly in developing countries from the mid-1950s onwards.[21]

In the 1980s, tension grew between population planning advocates and women's health activists who advanced women's reproductive rights as part of a human rights-based approach.[22] Growing opposition to the narrow population planning focus led to a significant change in population planning policies in the early 1990s.[23]

Population planning and economics

Opinions vary among economists about the effects of population change on a nation's economic health. US scientific research in 2009 concluded that the raising of a child cost about $16,000 yearly ($291,570 total for raising the child to its 18th birthday).[24] In the US, the multiplication of this number with the yearly population growth will yield the overall cost of the population growth. Costs for other developed countries are usually of similar order of magnitude.

Some economists, such as Thomas Sowell[25] and Walter E. Williams,[26] have argued that poverty and famine are caused by bad government and bad economic policies, not by overpopulation.

In his book The Ultimate Resource, economist Julian Simon argued that higher population density leads to more specialization and technological innovation, which in turn leads to a higher standard of living. He claimed that human beings are the ultimate resource since we possess "productive and inventive minds that help find creative solutions to man’s problems, thus leaving us better off over the long run".[27] He also claimed that, "Our species is better off in just about every measurable material way."[28]

Simon also claimed that when considering a list of countries ranked in order by population density, there is no correlation between population density and poverty and starvation. Instead, if a list of countries is considered according to corruption within their respective governments, there is a significant correlation between government corruption, poverty and famine.

Views on population planning

Population increase reductions

Support

As early as 1798, Thomas Malthus argued in his Essay on the Principle of Population for implementation of population planning. Around the year 1900, Sir Francis Galton said in his publication Hereditary Improvement: "The unfit could become enemies to the State, if they continue to propagate." In 1968, Paul Ehrlich noted in The Population Bomb, "We must cut the cancer of population growth", and "if this was not done, there would be only one other solution, namely the 'death rate solution' in which we raise the death rate through war-famine-pestilence etc.”

In the same year, another prominent modern advocate for mandatory population planning was Garrett Hardin, who proposed in his landmark 1968 essay Tragedy of the commons, society must relinquish the "freedom to breed" through "mutual coercion, mutually agreed upon." Later on, in 1972, he reaffirmed his support in his new essay "Exploring New Ethics for Survival", by stating, " We are breeding ourselves into oblivion." Many prominent personalities, such as Bertrand Russell, Margaret Sanger (1939), John D. Rockefeller, Frederick Osborn (1952), Isaac Asimov, Arne Næss[29] and Jacques Cousteau have also advocated for population planning. Today, a number of influential people advocate population planning such as these:

- David Attenborough[30]

- Michael E. Arth[31]

- Jonathon Porritt, UK sustainable development commissioner[32]

- Sara Parkin[33]

- Crispin Tickell[34]

- Christian de Duve, Nobel laureate[35]

The head of the UN Millennium Project Jeffrey Sachs is also a strong proponent of decreasing the effects of overpopulation. In 2007, Jeffrey Sachs gave a number of lectures (2007 Reith Lectures) about population planning and overpopulation. In his lectures, called "Bursting at the Seams", he featured an integrated approach that would deal with a number of problems associated with overpopulation and poverty reduction. For example, when criticized for advocating mosquito nets he argued that child survival was, "by far one of the most powerful ways," to achieve fertility reduction, as this would assure poor families that the smaller number of children they had would survive.[36]

Opposition

The Roman Catholic Church has opposed abortion, sterilization, and artificial contraception as a general practice but especially in regard to population planning policies.[37] Pope Benedict XVI has stated, "The extermination of millions of unborn children, in the name of the fight against poverty, actually constitutes the destruction of the poorest of all human beings."[38]

In Protestantism, one particular council with unknown affiliate churches wrote a "Reformed Theology ICCP Document Topic 24 Article 20" which states that "We affirm that human multiplication and filling of the Earth are intrinsically good (Genesis 1:28) and that, in principle, children, lots of them, are a blessing from God to their faithful parents and the rest of the Earth (Psalm 127; 128). We deny that the Earth is overpopulated; that “overpopulation” is even a meaningful term, since it cannot be defined by demographic quantities such as population density, population growth rate, or age distribution; and that godly dominion over the Earth requires population control or “family planning” to limit fertility."[39] The well-known Reformed Theology pastor Dr. Stephen Tong also opposes the planning of human population.[40]

Natalism

The Nation has criticised some white Quiverfull families for having large families motivated by racism and worries about "race suicide".[41]

Pro-natalist policies

In 1946, Poland introduced a tax on childlessness, discontinued in the 1970s, as part of natalist policies in the Communist government. From 1941 to the 1990s, the Soviet Union had a similar tax to replenish the population losses incurred during the Second World War.

The Socialist Republic of Romania under Nicolae Ceaușescu severely repressed abortion, (the most common birth control method at the time) in 1966,[42][43] and forced gynecological revisions and penalties for unmarried women and childless couples. The surge of the birth rate taxed the public services received by the decreţei 770 ("Scions of the Decree 770") generation. The Romanian Revolution of 1989 preceded a fall in population growth.

Balanced birth policies

Nativity in the Western world dropped during the interwar period. Swedish sociologists Alva and Gunnar Myrdal published Crisis in the Population Question in 1934, suggesting an extensive welfare state with universal healthcare and childcare, to increase overall Swedish birth rates, and level the number of children at a reproductive level for all social classes in Sweden. Swedish fertility rose throughout World War II (as Sweden was largely unharmed by the war) and peaked in 1946.

Modern practice by country

Australia

Australia currently offers a $5,000 bonus for every baby plus additional fortnightly payments, a free immunisation scheme, and recently proposed to pay all child care costs for women who want to work.

China

One-child era (1978-2014)

The most significant population planning system in the world was China's one-child policy, in which, with various exceptions, having more than one child was discouraged. Unauthorized births were punished by fines, although there were also allegations of illegal forced abortions and forced sterilization.[44] As part of China's planned birth policy, (work) unit supervisors monitored the fertility of married women and may decide whose turn it is to have a baby.[45]

The Chinese government introduced the policy in 1978 to alleviate the social and environmental problems of China.[46] According to government officials, the policy has helped prevent 400 million births. The success of the policy has been questioned, and reduction in fertility has also been attributed to the modernization of China.[47] The policy is controversial both within and outside of China because of its manner of implementation and because of concerns about negative economic and social consequences e.g. female infanticide. In oriental cultures, the oldest male child has responsibility of caring for the parents in their old age. Therefore, it is common for oriental families to invest most heavily in the oldest male child, such as providing college, steering them into the most lucrative careers, and so on. To these families, having an oldest male child is paramount, so in a one-child policy, a daughter has no economic benefit, so daughters, especially as a first child, is often targeted for abortion or infanticide. China introduced several government reforms to increase retirement payments to coincide with the one-child policy. During that time, couples could request permission to have more than one child.[48]

According to Tibetologist Melvyn Goldstein, natalist feelings run high in China's Tibet Autonomous Region, among both ordinary people and government officials. Seeing population control "as a matter of power and ethnic survival" rather than in terms of ecological sustainability, Tibetans successfully argued for an exemption of Tibetan people from the usual family planning policies in China such as the one-child policy.[49]

Two-child era (2014-)

In November 2014, the Chinese government allowed its people to conceive a second child under the supervision of government regulation.[50]

On October 29, 2015, the ruling Chinese Communist Party announced that all one-child policies would be scrapped, allowing all couples to have two children. The change was needed to allow a better balance of male and female children, and to grow the young population to ease the problem of paying for the aging population.

India

Only those with two or fewer children are eligible for election to a gram panchayat, or local government.

We two, our two ("Hum do, hamare do" in Hindi) is a slogan meaning one family, two children and is intended to reinforce the message of family planning thereby aiding population planning.

Facilities offered by government to its employees are limited to two children. The government offers incentives for families accepted for sterilization. Moreover, India was the first country to take measures for family planning back in 1951.

| “ | In the south west of India lies the long narrow coastal state of Kerala. Most of its thirty-two million inhabitants live off the land and the ocean, a rich tropical ecosystem watered by two monsoons a year. It's also one of India's most crowded states - but the population is stable because nearly everybody has small families.... At the root of it all is education. Thanks to a long tradition of compulsory schooling for boys and girls Kerala has one of the highest literacy rates in the World. Where women are well educated they tend to choose to have smaller families.... What Kerala shows is that you don't need aggressive policies or government incentives for birthrates to fall. Everywhere in the world where women have access to education and have the freedom to run their own lives, on the whole they and their partners have been choosing to have smaller families than their parents. But reducing birthrates is very difficult to achieve without a simple piece of medical technology, contraception. | ” |

| — BBC Horizon (2009), How Many People Can Live on Planet Earth | ||

Iran

After the Iran–Iraq War, Iran encouraged married couples to produce as many children as possible to replace population lost to the war.[51]

Iran succeeded in sharply reducing its birth rate from the late 1980s to 2010. Mandatory contraceptive courses are required for both males and females before a marriage license can be obtained, and the government emphasized the benefits of smaller families and the use of contraception.[52] This changed in 2012, when a major policy shift back towards increasing birth rates and against population planning was announced. In 2014, permanent contraception and advertising of birth control are to be outlawed.[53]

Israel

In Israel, Haredi families with many children receive economic support through generous governmental child allowances, government assistance in housing young religious couples, as well as specific funds by their own community institutions.[54] Haredi women have an average of 6.7 children while the average Jewish Israeli woman has 3 children.[55]

Japan

Japan has experienced a shrinking population for many years.[56] The government is trying to encourage women to have children or to have more children - many Japanese women do not have children, or even remain single. The population is culturally opposed to immigration.

Some Japanese localities, facing significant population loss, are offering economic incentives. Yamatsuri, a town of 7,000 just north of Tokyo, offers parents $4,600 for the birth of a child and $460 a year for 10 years.

Myanmar

In Myanmar, the Population planning Health Care Bill requires some parents to space each child three years apart.[57] The measure is expected to be used against the persecuted Muslim Rohingyas minority.[58]

Russia

Russian President Vladimir Putin directed Parliament in 2006 to adopt a 10-year program to stop the sharp decline in Russia's population, principally by offering financial incentives and subsidies to encourage women to have children.[59]

Singapore

Singapore has undergone two major phases in its population planning: first to slow and reverse the baby boom in the Post-World War II era; then from the 1980s onwards to encourage couples to have more children as the birth rate had fallen below the replacement-level fertility. In addition, during the interim period, eugenics policies were adopted.[60]

The anti-natalist policies flourished in the 1960s and 1970s: initiatives advocating small families were launched and developed into the Stop at Two programme, pushing for two-children families and promoting sterilisation. In 1984, the government announced the Graduate Mothers' Scheme, which favoured children of more well-educated mothers;[61] the policy was however soon abandoned due to the outcry in the general election of the same year.[62] Eventually, the government became pro-natalist in the late 1980s, marked by its Have Three or More plan in 1987.[63] Singapore pays $3,000 for the first child, $9,000 in cash and savings for the second; and up to $18,000 each for the third and fourth.[59]

Spain

In 2017, the government of Spain appointed a "minister for sex", in a pro-natalist attempt to reverse a negative population growth rate.[64]

Turkey

In May 2012, Turkey's Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan argued that abortion is murder and announced that legislative preparations to severely limit the practice are underway. Erdogan also argued that abortion and C-section deliveries are plots to stall Turkey's economic growth. Prior to this move, Erdogan had repeatedly demanded that each couple have at least three children.[65]

In 2017, he publicly advocated for Turks living in Europe to have at least 5 children, and also at the same time said they should drive the best cars, live in the best houses and consider their new countries their home – probably to annoy Europeans as revenge for some European governments banning pro-Erdogan referendum rallies organised by the Turkish government.

United States

Enacted in 1970, Title X of the Public Health Service Act provides access to contraceptive services, supplies and information to those in need. Priority for services is given to people with low incomes. The Title X Family Planning program is administered through the Office of Population Affairs under the Office of Public Health and Science. It is directed by the Office of Family Planning.[66] In 2007, Congress appropriated roughly $283 million for family planning under Title X, at least 90 percent of which was used for services in family planning clinics.[66] Title X is a vital source of funding for family planning clinics throughout the nation,[67] which provide reproductive health care.

The education and services supplied by the Title X-funded clinics support young individuals and low-income families. The goals of developing healthy families are accomplished by helping individuals and couples decide whether to have children and when the appropriate time to do so would be.[67]

Title X has made the prevention of unintended pregnancies possible.[67] It has allowed millions of American women to receive necessary reproductive health care, plan their pregnancies and prevent abortions. Title X is dedicated exclusively to funding family planning and reproductive health care services.[66]

Title X as a percentage of total public funding to family planning client services has steadily declined from 44% of total expenditures in 1980 to 12% in 2006. Medicaid has increased from 20% to 71% in the same time. In 2006, Medicaid contributed $1.3 billion to public family planning.[68]

Natalism in the United States

In a 2004 editorial in The New York Times, David Brooks expressed the opinion that the relatively high birthrate of the United States in comparison to Europe could be attributed to social groups with "natalist" attitudes.[69] The article is referred to in an analysis of the Quiverfull movement.[70] However, the figures identified for the demographic are extremely low.

Former US Senator Rick Santorum made natalism part of his platform for his 2012 presidential campaign.[71] This is not an isolated case. Many of those categorized in the General Social Survey as "Fundamentalist Protestant" are more or less natalist, and have a higher birth rate than "Moderate" and "Liberal" Protestants.[72] However, Rick Santorum is not a Protestant but a practicing Catholic.

Uzbekistan

It is reported that Uzbekistan has been pursuing a policy of forced sterilizations, hysterectomies and IUD insertions since the late 1990s in order to impose population planning.[73][74][75][76][77][78][79]

See also

- Birth control

- Birth credit

- Eugenics

- Human overpopulation

- List of population concern organizations

- Malthus' Dismal Theorem

- Overpopulation

- Steady-state economy

- Pledge two or fewer (campaign for small families)

- Voluntary Human Extinction Movement

Fiction

References

- ↑ Lifeblood: How to Change the World One Dead Mosquito at a Time, Alex Perry p9

- 1 2 Ryerson, William N. (2010). The Post Carbon Reader: Managing the 21st Century's Sustainability Crises, "Ch.12: Population: The Multiplier of Everything Else". Healdsburg, Calif.: Watershed Media. pp. 153–174. ISBN 978-0970950062.

- 1 2 3 Neurath, Paul (1994). From Malthus to the Club of Rome and Back. M.E. Sharpe. p. 7. ISBN 9781563244070.

- 1 2 Neurath, Paul (1994). From Malthus to the Club of Rome and Back. M.E. Sharpe. p. 6. ISBN 9781563244070.

- ↑ Neurath, Paul (1994). From Malthus to the Club of Rome and Back. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9781563244070.

- 1 2 3 Neurath, Paul (1994). From Malthus to the Club of Rome and Back. M.E. Sharpe. p. 8. ISBN 9781563244070.

- 1 2 Neurath, Paul (1994). From Malthus to the Club of Rome and Back. M.E. Sharpe. p. 10. ISBN 9781563244070.

- 1 2 3 4 Neurath, Paul (1994). From Malthus to the Club of Rome and Back. M.E. Sharpe. p. 9. ISBN 9781563244070.

- ↑ Neurath, Paul (1994). From Malthus to the Club of Rome and Back. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9781563244070.

- 1 2 Rosenberg, M. (2007, September 09)3-2. Thomas Malthus on Population. Retrieved June 20, 2009, from About.com "Geography Web site"

- 1 2 Knudsen, Lara (2006). Reproductive Rights in a Global Context. Vanderbilt University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780826515285.

- ↑ Bleier, R. The Home Page of the International Society of Malthus. Retrieved June 20, 2009, from The International Society of Malthus Web site: http://desip.igc.org/malthus/principles.html

- ↑ Thomas Robert Malthus, 1766-1834. Retrieved June 20, 2009, from The History of Economic Thought Website

- ↑ Knudsen, Lara (2006). Reproductive Rights in a Global Context. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780826515285.

- 1 2 Knudsen, Lara (2006). Reproductive Rights in a Global Context. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780826515285.

- ↑ Knudsen, Lara (2006). Reproductive Rights in a Global Context. Vanderbilt University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780826515285.

- ↑ Bradshaw, Corey J. A. (2014). "Human population reduction is not a quick fix for environmental problems". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (46): 16610–16615. doi:10.1073/pnas.1410465111. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- ↑ Spears, Dean. "Smaller human population in 2100 could importantly reduce the risk of climate catastrophe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (18): E2270. PMC 4426416

. PMID 25848063. doi:10.1073/pnas.1501763112. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

. PMID 25848063. doi:10.1073/pnas.1501763112. Retrieved May 8, 2016. - ↑ McGrath, Matt (October 27, 2014). "Population controls 'will not solve environment issues'". BBC. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- 1 2 Whaley Eager, Paige (2004). Global Population Policy. Ashgate Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 9780754641629.

- ↑ Whaley Eager, Paige (2004). Global Population Policy. Ashgate Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 9780754641629.

- ↑ Knudsen, Lara (2006). Reproductive Rights in a Global Context. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 2. ISBN 9780826515285.

- ↑ Knudsen, Lara (2006). Reproductive Rights in a Global Context. Vanderbilt University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9780826515285.

- ↑ Abbott, Charles (August 4, 2009). "Pricetag to raise a child -- $291,570, says U.S". Reuters.

- ↑ Thomas Sowell Julian Simon, combatant in a 200-year war Thomas Sowell, February 12, 1998

- ↑ Population control nonsense Walter Williams, February 24, 1999

- ↑ Moore, S. (1998, March/April). Julian Simon Remembered: it's a Wonderful Life. Retrieved June 25, 2009, from CATO Institute Web site

- ↑ Regis, E. (1997, February). The Doomslayer. Retrieved June 20, 2009, from Wired.com site

- ↑ Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke (1998). Hitler's Priestess: Savitri Devi, the Hindu-Aryan Myth, and Neo-Nazism. NY: New York University Press, ISBN 0-8147-3110-4

- ↑ Leake, Jonathan (August 3, 2003). "Attenborough cut population by half". The Times. London.

- ↑ Corrupt.org, Interview with Michael E. Arth

- ↑ Schwarz, Walter (September 1, 2004). "Crowd control". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ Local to Global: Kingston University

- ↑ The green diplomat: Sir Crispin Tickell

- ↑ Lloyd, Robin (30 June 2011) Laureate urges next generation to address population control as central issue Scientific Americain, Retrieved 9 April 2012

- ↑ BBC.co.uk Bursting at the Seams

- ↑ Saunders, William. "Church Has Always Condemned Abortion". Catholic News Agency. Arlington Catholic Herald. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- ↑ Vatican.va

- ↑ Concerning The Biblical Perspective of Environmental Stewardship

- ↑ https://ww123.net/redirect.php?tid=4862770&goto=lastpost 唐崇荣牧师 圣经难解经文 第二十九讲 诺亚咒诅迦南, Retrieved 22 Mar 2017.

- ↑ Kathryn Joyce (9 November 2006). "Arrows for the War". The Nation. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ↑ Scarlat, Sandra (May 17, 2005), "'Decreţeii': produsele unei epoci care a îmbolnăvit România" [Scions of the Decree': Products of an Era that Sickened Romania], Evenimentul Zilei (in Romanian).

- ↑ Kligman, Gail (1998), The Politics of Duplicity. Controlling Reproduction in Ceausescu's Romania, Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- ↑ Arthur E. Dewey, Assistant Secretary for Population, Refugees and Migration Testimony before the House International Relations Committee Washington, DC December 14, 2004 http://statelists.state.gov/scripts/wa.exe?A2=ind0412c&L=dossdo&P=401

- ↑ http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+cn0081)

- ↑ Pascal Rocha da Silva, "La politique de l'enfant unique en République Populaire de Chine", 2006, Université de Genève, p. 22-28., cf. Sinoptic.ch Archived 2007-11-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Has China's one-child policy worked?". BBC News. September 20, 2007.

- ↑ Fisher, Max (November 16, 2013). "China’s rules for when families can and can’t have more than one child". Washington Post. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- ↑ Goldstein, Melvyn; Cynthia, Beall (March 1991). "China's Birth Control Policy in the Tibet Autonomous Region". Asian Survey. 31 (3): 285–303. doi:10.1525/as.1991.31.3.00p0043x.

- ↑ "Why China's Second-Baby Boom Might Not Happen". Bloomberg.

- ↑ Beaugé, Florence (2 February 2016). "‘Get back to your washing machine’: Iran’s ambitious women". mondediplo.com. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Iran's Birth Rate Plummeting at Record Pace

- ↑ Iran to ban permanent contraception after Islamic cleric's edict to increase population

- ↑ Dov Friedlander (2002). "Fertility in Israel: Is the Transition to Replacement Level in Sight?

Part of: Completing the Fertility Transition." (PDF). United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. - ↑ Paul Morland (April 7, 2014). "Israeli women do it by the numbers". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ "Japan's demography: the incredible shrinking country". The Economist. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ↑ "Myanmar president signs off on contested population law". London: Associated Press via Daily Mail). 24 May 2015.

- ↑ "Rohingyas: Still in peril: Myanmar’s repression of Rohingyas continues apace". The Economist. SINGAPORE. 6 June 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

This measure grants local authorities the power to mandate that mothers in areas deemed to have high rates of population growth have children no fewer than three years apart. Buddhist chauvinists in Myanmar have fomented fears of high birth rates among Muslims; this measure is likely to be used against Rohingyas.

- 1 2 C. J. Chivers (May 11, 2006). "Putin Urges Plan to Reverse Slide in the Birth Rate". New York Times.

- ↑ Theresa Wong and Brenda S.A. Yeoh (June 2003), Fertility and the Family: An Overview of Pro-natalist Population Policies in Singapore (PDF), Asian MetaCentre Research Paper Series (12)

- ↑ Pekka Louhiala (2004). Preventing intellectual disability: ethical and clinical issues. Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-521-53371-3.

- ↑ Quah, Jon (1985). "Singapore in 1984: Leadership Transition in an Election Year". Asian Survey. 25: 225. JSTOR 2644306. doi:10.1525/as.1985.25.2.01p0247v.

- ↑ "Singapore: Population Control Policies". Library of Congress Country Studies (1989). Library of Congress. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- ↑ "Spain appoints 'sex tsar' in bid to boost declining population". The Independent. 25 February 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ↑ "US, Turkey: abortion" (article). Reuters. 2012-06-03.

- 1 2 3 Office of Population Affairs

- 1 2 3 Planned Parenthood, Title X

- ↑ Sonfield A, Alrich C and Gold RB, Public funding for family planning(in terms of children per family), sterilization and abortion services, FY 1980–2006, Occasional Report, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2008, No. 38.

- ↑ Brooks, David (2004-12-07), "The New Red-Diaper Babies", The New York Times, retrieved 21 Jan 2006.

- ↑ Joyce, Kathryn (27 November 2006), "'Arrows for the War'", The Nation, retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ Seung Min Kim (15 January 2012). "Santorum: More babies, please!". Politico.

- ↑ "Modern Protestant Natalism". Dialog. Wiley. 49: 133–140. 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6385.2010.00517.x.

- ↑ Birth Control by Decree in Uzbekistan IWPR Institute for War & Peace Reporting, published 2005-11-18, accessed 2012-04-12

- ↑ BBC News: Uzbekistan's policy of secretly sterilising women BBC, published 2012-04-12, accessed 2012-04-12

- ↑ Crossing Continents: Forced Sterilisation in Uzbekistan BBC, published 2012-04-12, accessed 2012-04-12

- ↑ Uzbeks Face Forced Sterilization The Moscow Times published 2010-03-10, accessed 2012-04-12

- ↑ Shadow Report: UN Committee Against Torture United Nations, authors Rapid Response Group and OMCT, published November 2007, accessed 2012-04-12

- ↑ Antelava, Natalia (12 April 2012). "Uzbekistan's policy of secretly sterilising women". BBC World Service.

- ↑ Antelava, Natalia (12 April 2012). "Uzbekistan's policy of secretly sterilising women". BBC World Service.

Further reading

- Mandani, Mahmood (1972). The Myth of Population Control: Family, Caste, and Class in an Indian Village, in series, Modern Reader. First Modern Reader Pbk. ed. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1973, cop. 1972. 173 p. SBN 85345-284-9

- Warren C. Robinson; John A. Ross (2007). The global family planning revolution: three decades of population policies and programs. World Bank Publications. ISBN 978-0-8213-6951-7.

- Thomlinson, R. 1975. Demographic Problems: Controversy over Population Control. 2nd ed. Encino, CA: Dickenson.

External links

- The Environmental Politics of Population and Overpopulation A University of California, Berkeley summary of historical, contemporary and environmental concerns involving overpopulation

- UNmilleniumProject.org, UN Millennium Project, retrieved June 20, 2009.

- YAN Kun(2011). The tendency equation of the population and its limit value in the United Kingdom (Brief annotation of the connection equation(R), p3-p5), Xi'an: Xi'an Modern Nonlinear Science Applying Institute.