Human–animal communication

Human–animal communication is the communication observed between humans and other animals, from non-verbal cues and vocalizations through to, potentially, the use of a sophisticated language.

Introduction

Human–animal communication is easily observed in everyday life. The interactions between pets and their owners, for example, reflect a form of spoken, while not necessarily verbal dialogue. A dog being scolded does not need to understand every word of its admonishment, but is able to grasp the message by interpreting cues such as the owner's stance, tone of voice, and body language. This communication is two-way, as owners can learn to discern the subtle differences between barks and meows, one hardly has to be a professional animal trainer to tell the difference between the bark of an angry dog defending its home and the happy bark of the same animal while playing. While these Pavlovian originating theories may hold true, current nonscientific evidence may point in other directions. Nonetheless, communication (often nonverbal) is also significant in equestrian activities such as dressage.

Word repetition in birds

Although some word repetition skills observed in some birds (most famously parrots) should not be mistaken for linguistic communication, studies have shown that parrots are able to use words meaningfully in linguistic tasks.[1] In particular, the African grey Alex demonstrated that birds may be able to use basic reason and speak creatively.[2] Fictional portrayals of sentient talking parrots and similar birds are common in children's fiction, such as the talking, loud-mouth parrot Iago of Disney's Aladdin. Bruce Thomas Boehner's book Parrot Culture: Our 2,500-Year-Long Fascination with the World's Most Talkative Bird explores this issue thoroughly.

The next level: language

Achieving a deeper level of communication between animals and humans has long been a goal of science. Perhaps the most famous example of recent decades has been Koko, a gorilla who is supposedly able to communicate with humans using a system based on American Sign Language with a "vocabulary" of over 1000 words.

John Lilly and cetacean communication

In the 1960s, John Lilly, M.D., prolific writer and explorer of consciousness via the isolation tank (his invention), and contemporary and associate of Timothy Leary, began experiments in the Virgin Islands aiming to establish meaningful communication between humans and the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus). Lilly financed, mostly personally, a human-dolphin cohabitat, a house on the ocean's shore that contained an area that was partially flooded and allowed a human and dolphin to live together in the same space, sharing meals, play, language lessons, and even sleep.

Two experiments of this sort are explained in detail in Lilly's popular books (see John Lilly for bibliography). The first experiment was more of a test run to check psychological and other strains on the human and cetacean participants, determining the extent of the need for other human contact, dry clothing, time alone, and so on. Despite tensions after several weeks, the experimenter, Margaret Howe Lovatt, agreed to a 2 1⁄2-month experiment, living isolated with a dolphin named Peter.

A basic outline of Peter dolphin's linguistic progress is as follows: early lessons involved mostly noise and interruptions from Peter during English lessons, and a food reward of fish was necessary for him to 'attend class.' After several weeks, a concerted effort by Peter to imitate the instructor's speech was evident, and human-like sounds were apparent, and recorded. More interesting was the dolphin's immediate grasp of basic semantics, such as the different aural indicators for 'ball' and 'doll' and other toys present in the aquarium. Peter was able to perform tasks such as retrieval on the (aurally) indicated object without fail. Later in the project the dolphin's ability to process linguistic syntax was made apparent, in that Peter could distinguish between the commands (e.g., only) "Bring the ball to the doll," and "Bring the doll to the ball." This ability not only demonstrates the bottlenose dolphin's grasp of basic grammar, but also implies the dolphins' own language must include some such syntactical rules. The correlation between length and 'syllables' (bursts of the dolphin's sound) with the instructor's speech also went from essentially zero at the beginning of the session to almost a perfect correlation by its completion. I.e., a sentence spoken by the instructor involving 35 syllables and lasting 8 seconds would be met with an 8-second burst of sound from Peter dolphin involving 35 easily discernible 'syllables' or bursts of sound.

Much later, experiments by Louis Herman, a former collaborator and student of Lilly's, demonstrated the crossmodal perceptual ability of dolphins. Dolphins typically perceive their environment through sound waves generated in the melon of their skulls, through a process known as echolocation (similar to that seen in bats, though the mechanism of production is different). The dolphin's eyesight however is also fairly good, even by human standards, and Herman's research found that any object, even of complex and arbitrary shape, identified either by sight or sound by the dolphin, could later be correctly identified by the dolphin with the alternate sense modality with almost 100 per cent accuracy, in what is classically known in psychology and behaviorism as a match-to-sample test. The only errors noted were presumed to have been a misunderstanding of the task during the first few trials, and not an inability of the dolphin's perceptual apparatus. This capacity is strong evidence for abstract and conceptual thought in the dolphin's brain, wherein an idea of the object is stored and understood not merely by its sensory properties; such abstraction may be argued to be of the same kind as complex language, mathematics, and art, and implies a potentially very great intelligence and conceptual understanding within the brains of tursiops and possibly many other cetaceans. Accordingly, Lilly's interest later shifted to whale song and the possibility of high intelligence in the brains of large whales, and Louis Herman's research at the now misnomered Dolphin Institute in Honolulu, Hawaii, focuses exclusively on the Humpback whale.

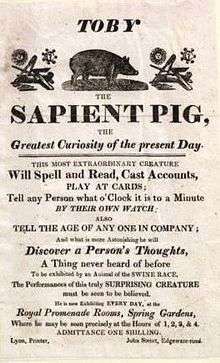

Animal communication as entertainment

Though animal communication has always been a topic of public comment and attention, for a period in history it surpassed this and became sensational popular entertainment. From the late 18th century through the mid 19th century, a succession of "learned pigs" and various other animals were displayed to the public in for-profit performances, boasting the ability to communicate with their owners (often in more than one language), write, solve math problems, and the like. One poster dated 1817 shows a group of "Java sparrows" who are advertised as knowing seven languages, including Chinese and Russian.

BowLingual

One real-world example of a technological means of one-way human–animal communication is BowLingual, a Japanese device which claims to translate barks from dozens of different breeds of dogs, including mixed-breeds. Based largely on Dr. Matsumi Suzuki's Animal Emotion Analysis System developed at Japan Acoustic Laboratory, the device outputs one of 200 phrases (grouped into six different moods), supposedly reflecting "meaning" of the dog's bark. The device was apparently successful enough in Japan to be brought to the American market, and was even named one of 2002's best inventions by Time Magazine. However, reports of the BowLingual's accuracy have been mixed at best, with popular product-review website Epinions giving it a low 1.5 stars average.

See also

- Alex (parrot)

- Animal cognition

- Animal communication

- Animal consciousness

- Animal intelligence

- Clever Hans

- Great ape language

- Talking animal

- Interspecies communication

Bibliography

- Sebeok, Thomas – Essays in Zoosemiotics (1990) ISSN 0838-5858

- Myers, Arthur – Communicating With Animals: The Spiritual Connection Between People and Animals (1997) ISBN 0-8092-3149-2

- Boehner, Bruce Thomas – Parrot Culture: Our 2,500-Year-Long Fascination with the World's Most Talkative Bird (2004) ISBN 0-8122-3793-5

- Summers, Patty – Talking With the Animals (1998) ISBN 1-57174-108-9

- Jay, Ricky – Learned Pigs and Fireproof Women (1987) ISBN 0-446-38590-5

- Gurney, Carol – The Language of Animals: 7 Steps to Communicating with Animals (2001) ISBN 0-440-50912-2

- Grandin, Temple – Animals in Translation: Using the Mysteries of Autism to Decode Animal Behavior (2004) ISBN 0-7432-4769-8