Hull House

|

Hull House | |

.tif.jpg) Hull House in the early 20th century | |

| |

| Location | 800 S. Halsted, Chicago, Illinois |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°52′18″N 87°38′51″W / 41.87167°N 87.64750°WCoordinates: 41°52′18″N 87°38′51″W / 41.87167°N 87.64750°W |

| Area | 1 acre (0.40 ha) |

| Built | building built in 1856, institution founded September 18, 1889 |

| Architect | Pond and Pond |

| Architectural style | Italianate[1] |

| NRHP Reference # | 66000315[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | June 23, 1965[2] |

| Designated CL | June 12, 1974 |

Hull House was a settlement house in the United States that was co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. Located in the Near West Side of Chicago, Illinois, Hull House (named for the home's first owner) opened its doors to recently arrived European immigrants. By 1911, Hull House had grown to 13 buildings. In 1912 the Hull House complex was completed with the addition of a summer camp, the Bowen Country Club.[3][4][5] With its innovative social, educational, and artistic programs, Hull House became the standard bearer for the movement that had grown, by 1920, to almost 500 settlement houses nationally.[6]

Most of the Hull House buildings were demolished for the construction of the University of Illinois-Circle Campus in the mid 1960s. The Hull mansion and several subsequent acquisitions were continuously renovated to accommodate the changing demands of the association. The original building and one additional building (which has been moved 200 yards (182.9 m))[7] survive today. On June 12, 1974, the Hull House building was designated a Chicago Landmark.[8] On June 23, 1965, it was designated as a U.S. National Historic Landmark .[9] On October 15, 1966, which is the day that the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 was enacted, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Hull House was one of the four original members to be listed on both the Chicago Registered Historic Places and the National Register of Historic Places list (along with Chicago Pile-1, Robie House & Lorado Taft Midway Studios).[1] The Hull House Association ceased operations in January 2012, but the Hull mansion and a related dining hall remain open as a museum.

Mission

Addams followed the example of Toynbee Hall, which was founded in 1884 in the East End of London as a center for social reform. She described Toynbee Hall as "a community of university men" who, while living there, held their recreational clubs and social gatherings at the settlement house among the poor people and in the same style they would in their own circle.[10] Addams and Starr established Hull House as a settlement house on September 18, 1889.[11]

In the 19th century a women's movement began to promote education, autonomy, and break into traditionally male dominated occupations for women. Organizations led by women, bonded by sisterhood, were formed for social reform, including settlement houses in working class and poor neighborhoods, like Hull House. To develop "new roles for women, the first generation of New Women wove the traditional ways of their mothers into the heart of their brave new world. The social activists, often single, were led by educated New Women.[12]

Hull House became, at its inception in 1889, "a community of university women" whose main purpose was to provide social and educational opportunities for working class people (many of them recent European immigrants) in the surrounding neighborhood. The "residents" (volunteers at Hull were given this title) held classes in literature, history, art, domestic activities (such as sewing), and many other subjects. Hull House also held concerts that were free to everyone, offered free lectures on current issues, and operated clubs for both children and adults.

In 1892, Addams published her thoughts on what has been described as "the three R's" of the settlement house movement: residence, research, and reform. These involved "close cooperation with the neighborhood people, scientific study of the causes of poverty and dependence, communication of these facts to the public, and persistent pressure for [legislative and social] reform..."[13] Hull House conducted careful studies of the Near West Side, Chicago community, which became known as "The Hull House Neighborhood". These studies enabled the Hull House residents to confront the establishment, eventually partnering with them in the design and implementation of programs intended to enhance and improve the opportunities for success by the largely immigrant population.[14]

According to Christie and Gauvreau (2001), while the Christian settlement houses sought to Christianize, Jane Addams, “had come to epitomize the force of secular humanism.” Her image was, however, “reinvented” by the Christian churches.[15] According to the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum, "Some social settlements were linked to religious institutions. Others, like Hull-House [co-founded by Addams], were secular."[16]

The Hull House neighborhood

One of the first newspaper articles ever written about Hull House[17] quotes the following invitation sent to the residents of the Hull House neighborhood. It begins with: "Mio Carissimo Amico"…and is signed, Le Signorine, Jane Addams and Ellen Starr. That invitation to the community, written during the first year of Hull House's existence, suggests that the inner core of what Addams labeled "The Hull House Neighborhood" was overwhelmingly Italian at that time. "10,000 Italians lived between the river and Halsted Street."[18]

By all accounts, the greater Hull House neighborhood (Chicago's Near West Side) was a mix of various ethnic groups that had immigrated to Chicago. There was no discrimination of race, language, creed, or tradition for those who entered the doors of the Hull House. Every person was treated with respect. The Bethlehem-Howard Neighborhood Center records substantiate that, "Germans and Jews resided south of that inner core (south of twelfth street)…The Greek delta formed by Harrison, Halsted and Blue Island Streets served as a buffer to the Irish residing to the south and the Canadian–French to the northwest. From the river on the east end, on out to the western ends of what came to be known as "Little Italy"—(from Roosevelt Road on the south to the Harrison Street delta on the north)—became the port-of-call for Italians who continued to immigrate to Chicago from the shores of southern Italy until a quota system was implemented in 1924 for most southern Europeans.[4]

The Greektown and Maxwell Street residents, along with the remnants of other immigrant groups living on the outer fringes of the Hull House Neighborhood, disappeared long before the physical demise of Hull House. The exodus of most ethnic groups began shortly after the turn of the twentieth century. Their businesses, e.g. Greektown and Maxwell Street, however, remained. Italian Americans were the only immigrant group that endured as a vibrant on-going community. That community came to be known as "Little Italy". Taylor Street's Little Italy, the inner core of Addams' "Hull House Neighborhood", remained as the laboratory upon which the social and philanthropic groups of Hull House elitists had tested their theories and formulated their challenges to the establishment.[3]

The synergy between Taylor Street’s Little Italy and the Hull House complex; i.e., the settlement house and its summer camp, the Bowen Country Club, is well documented.[3] Alice Hamilton, medical professional and early member of that elite Hull House hierarchy, wrote in her autobiography, "Those Italian women knew what a baby needed, far better than my Ann Arbor professors did." [19] The ancillary literature between, among and about members of Hull House's inner sanctum of sociologists and philanthropists is littered with such comments, reinforcing the relationship that existed between Taylor Street's Little Italy and Hull House. A review of the ethnic composition of those who registered for and utilized the services provided by the Hull House complex, during its 74 years as a tenant of the near-west side, suggests an ethnic bias. Of the 257 known WWII veterans who were alumni of the Bowen Country Club, "virtually all had a vowel at the end of their names...denoting their Italian heritage."[3]

A historic picture, "Meet the Hull House Kids," was taken on a summer day in 1924 by Wallace K. Kirkland Sr., Hull House Director. He later became a top photographer with Life. The twenty Hull House Kids were erroneously described as young boys, of Irish ancestry, posing in the Dante School yard on Forquer Street (now Arthington Street). It circulated the world as a "poster child" of sorts for the Hull House social experiment. On April 5, 1987, over a half century later, the Chicago Sun-Times refuted the contention that the Hull House Boys were of Irish ancestry. In doing so, the Sun-Times article listed the names of each of the young boys.[20] All twenty boys were first-generation Italian-Americans, all with vowels at the end of their names. "They grew up to be lawyers and mechanics, sewer workers and dump truck drivers, a candy shop owner, a boxer and a mob boss."

Because of the immigrants’ loneliness for their homeland, Addams started hosting ethnic evenings at Hull House. This would include ethnic food, dancing, music, and maybe a short lecture on a topic of interest. Some of the themed evenings were Italian, Greek, German, Polish, etc. Ellen Gates Starr described one Italian evening as having the room packed full with people. One of the ladies who attended “recited a patriotic poem with great spirit” and everyone was moved by it.[21]

Accomplishments

Throughout the first two decades, along with thousands of immigrants from the surrounding area, Hull House attracted many female residents who later became prominent and influential reformers at various levels.[6] At the beginning, Addams and Starr volunteered as on-call doctors when the real doctors either didn't show up or weren't available. They acted as midwives, saved babies from neglect, prepared the dead for burial, nursed the sick, and sheltered domestic violence victims. For example, one Italian bride had lost her wedding ring and in turn was beaten by her husband for a week. She sought shelter at the settlement and it was granted to her. Also, a baby born with a cleft palate was unwanted by his mother so he was kept at the Hull House for six weeks after an operation. In another case, a woman was about to give birth to an illegitimate baby, so none of the Irish matrons would touch it. Addams and Starr stepped in and delivered this helpless little one. Finally, a female Italian immigrant was so thrilled about fresh roses at one of the Hull House receptions that she insisted they had come from Italy. She had never seen anything as beautiful in America despite the fact that she lived within ten blocks of a florist shop. Her limited view of America came from the untidy street she lived on and the long struggle to adapt to American ways.[22] The settlement was also gradually drawn into advocating for legislative reforms at the municipal, state and federal levels, addressing issues such as child labor, women's suffrage, healthcare reform and immigration policy. Some claim that the work of the Hull House marked the beginning of what we know today as "Social Welfare".[23]

At the neighborhood level, Hull House established the city’s first public playground, bathhouse, and public gymnasium (in 1893), pursued educational and political reform, and investigated housing, working, and sanitation issues.[6] The playground opened on May Day in 1893, located on Polk Street. Families dressed in party attire and came to join the celebration that day. Addams became the founder of the National Playground Association and advocated for playgrounds nationwide. She had studied child behavior and painfully concluded that “children robbed of childhood were likely to become dull, sullen men and women working mindless jobs, or criminals for whom the adventure of crime became the only way to break out of the bleakness of their lives” [24] Also, one volunteer, Jenny Dow, started a kindergarten class for children left at the settlement while their mothers worked in the sweatshops. Within three weeks, Dow had 24 registered kindergartners and 70 on a waiting list.[25] At the municipal level, their pursuit of legal reforms led to the first juvenile court in the United States, and their work influenced urban planning and the transition to a branch library system.[6] At the state level Hull House influenced legislation on child labor laws, occupational safety and health provisions, compulsory education, immigrant rights, and pension laws.[6] These experiences translated to success at the federal level, working with the settlement house network to champion national child labor laws, women’s suffrage, a children’s bureau, unemployment compensation, workers' compensation, and other elements of the Progressive agenda during the first two decades of the twentieth century.[6]

Teachings

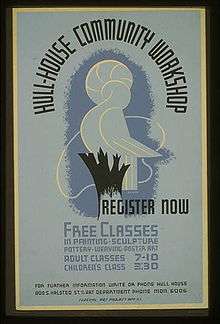

Later, the settlement branched out and offered services to ameliorate some of the effects of poverty. A public dispensary provided nutritious food for the sick as well as a daycare center and public baths. Among the courses Hull House offered was a bookbinding course, which was timely — given the employment opportunities in the growing printing trade.[26] Hull House was well known for its success in aiding American assimilation, especially with immigrant youth.[27] Hull House became the center of the movement to promote hand workmanship as a moral regenerative force.[28] Under the direction of Laura Dainty Pelham their theater group performed the Chicago premiers of several plays by John Galsworthy, Henrik Ibsen, and George Bernard Shaw, and was given credit for founding the American Little Theatre Movement.[29] The success of Hull House led Paul Kellogg to refer to the group as the "Great Ladies of Halsted Street".[30]

The objective of Hull House, as stated in its charter, was: "To provide a center for a higher civic and social life; to institute and maintain educational and philanthropic enterprises, and to investigate and improve the conditions in the industrial districts of Chicago."[31]

The building and museum

Hull House was located in Chicago, Illinois, and took its name from the Italianate mansion built by real estate magnate Charles Jerald Hull (1820-1889) at 800 South Halsted Street in 1856. The building was located in what had once been a fashionable part of town, but by 1889, when Addams was searching for a location for her experiment, it had descended into squalor. This was partly due to the rapid and overwhelming influx of immigrants into the Near West Side neighborhood. Charles Hull granted his former home to his niece Helen Culver, who in turn granted it to Addams on a 25-year rent-free lease. By 1907, Addams had acquired 13 buildings surrounding Hull's mansion. Between 1889 and 1935, Addams and Ellen Gates Starr continuously redeveloped the building.[7] In 1912, the Bowen Country Club summer camp was added to complete the Hull House complex. The facility remained at the original location until it was purchased in 1963 by what was then called the University of Illinois-Circle Campus.[32] The development of University of Illinois-Circle Campus required the demolition of most of the Hull House buildings[7] and the 1967 restoration to the original building by Frazier, Raftery, Orr and Fairbank removed Addams's third floor addition. In addition to the mansion, of the dozen additional buildings only the craftsman style dining hall (built in 1905 and designed by Pond & Pond) survives and it was moved 200 yards (182.9 m) from its original site to be next to the mansion.[7][33]

The haunting of Hull House

Addams noted upon moving in that the building had a "half skeptical reputation for a haunted attic."[34] Over the years, numerous stories of ghosts and hauntings have surrounded Hull House, making it a stop on many of the "ghosts in Chicago" tours. Charles Hull's wife had died in the house in 1860, and is sometimes thought to haunt it.[35] Other candidates for resident ghosts include the many people who died there of natural causes in the 1870s when it was used as a home for the aged by the Little Sisters of the Poor.[35]

In 1913, another Hull House ghost story began circulating. According to this legend, after a man claimed that he would rather have the Devil in his house than a picture of The Virgin Mary, his child was born with pointed ears, horns, scale-covered skin, and a tail. The mother was said to have taken the baby to Hull House, where Addams was said to have attempted to have it baptized and wound up locking it in the attic.[36] While initially annoyed about the story, which had no basis in fact, Addams became fascinated by the effect the episode had on old women in the neighborhood and used the episode as a basis for her book, The Long Road of Woman's Memory.[37]

While a great many erroneous stories have circulated about the building, Addams is known to have spoken to several friends about one of the front bedrooms on the second floor being haunted - she and a friend once thought they saw a "woman in white" ghost there, and the same ghost was later seen by a group of girls when the room was used as a dressing room for the adjacent theater. Though Addams called it "haunted," she seems to have been more amused than frightened by it.[35]

Theater

Addams felt that the community benefits from theater plays and thus established an amateur theater in the Hull House in 1899.[38] “The neighborhood Greeks performed the classic plays of antiquity in their own language and the children of European immigrants produced Shakespeare” as well as others.[39] Early one December, the Greeks performed Odysseus in Chicago. The auditorium was filled with a multi-ethnic crowd and packed too close for comfort. The audience was very eager and gave the performers “rapt attention."[40] They watched neighbors and co-workers execute this primitive play, but it was very powerful, plausible, and personal. The actors seemed to pay “tribute to a noble ancestry” and plea for the respect of the audience.[40] Indeed, they did gain this respect because it was said that not even trained college students could give the same play with as much zeal and patriotism.[40] In 1963, when road tours of Broadway productions became common, the Hull House Theater in the Jane Addams Center at 3212 North Broadway fostered the development of Chicago Theater companies for the rest of the century.[38] Founder Bob Sickinger created an environment to nourish young talent with professionalism.[41] Chicago's noted improvisational theatre scene has roots in Hull House, as Viola Spolin, noted improvisational techniques instructor, taught classes at Hull House.[42]

1930s to 2012

Addams ran Hull House as head resident until her death in 1935. Hull House continued to serve the community surrounding the Halsted location until it was displaced by the urban branch campus of the University of Illinois in the 1960s. Until 2012, the social service center role was performed throughout the city at various locations under an umbrella organization, the Jane Addams Hull House Association.[6] The original Hull House building itself is a museum, part of the College of Architecture and the Arts at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and is open to the public.

The Jane Addams Hull House Association was one of Chicago’s largest nonprofit social welfare organizations. Its mission was to improve social conditions for underserved people and communities by providing creative, innovative programs and by advocating for related public policy reforms. The Association had more than 50 programs at over 40 sites throughout Chicago and served approximately 60,000 individuals, families, and community members every year.[43]

The Jane Addams Hull-House Museum is part of the College of Architecture and the Arts at the University of Illinois at Chicago and serves as a memorial to Addams and other resident social reformers, whose work influenced the lives of their immigrant neighbors, as well as national and international public policy. The museum and its programs connect the work of Hull House residents to important contemporary social issues. The Museum's collection includes over 1,100 artifacts related to Hull House history and over 100 oral interviews conducted with people who have shared their stories about Hull House and the surrounding neighborhood.[44]

Hull House Association closure

On January 19, 2012, it was announced that Jane Addams Hull House Association would close in the spring of 2012 and file for bankruptcy due to financial difficulties, after 122 years.[45] On Friday, January 27, 2012, Hull House closed unexpectedly and all employees received their final paychecks.[46] Employees learned at time of closing that they would not receive severance pay or earned vacation pay or healthcare coverage.[47] Union officials said that the agency closed while owing employees more than $27,000 in unpaid expense reimbursement claims.[48] The University of Illinois at Chicago's Jane Addams Hull-House Museum (unaffiliated with the agency), however, will remain open.[49]

Selected notable residents

- Edith Abbott

- Grace Abbott

- Jane Addams

- Ethel Percy Andrus

- Viola Spolin

- Neva Boyd

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- Sophonisba Breckinridge

- Edward L Burchard, the first male resident

- Dorothy Detzer

- Pauline Gibling Schindler

- Henry Standing Bear

- Alice Hamilton

- Florence Kelley

- Mary Kenney O'Sullivan

- Julia Lathrop

- Mary McDowell

- Ernest Carroll Moore, founder and first provost of UCLA.

- Frances Perkins

- Gerard Swope, General Electric Company (1922-1939)[50]

- Alzina Stevens

- Cornelia De Bey

- Eleanor Clarke Slagle, founder of occupational therapy

- Victor Yarros and Rachelle Yarros

- Enella Benedict

- Emily Edwards(de Cantabrana)

- Willard Motley, author: Knock on Any Door. Resident writer at Hull House, Willard Motley used the Hull House Neighborhood, Taylor Street's Little Italy, and its people for the setting of his 1949 best seller. Taylor Street Archives

Selected notable alumni

See also

- Jane Addams Burial Site

- John H. Addams

- John H. Addams Homestead

- History of social work

- Hull House Music School

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Hull House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Taylor Street Archives

- 1 2 Hull House Museum

- ↑ Jane Addams, Twenty Years at Hull House

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Johnson, Mary Ann (2004). Grossman, James R., Keating, Ann Durkin, and Reiff, Janice L., eds. "Hull House". The Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society.

- 1 2 3 4 Schulte, Franz and Kevin Harrington, Chicago's Famous Buildings, fifth edition, University of Chicago Press, 2004, pp. 212-3, ISBN 0-226-74066-8.

- ↑ "Jane Addams' Hull House". City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development, Landmarks Division. 2003. Retrieved March 6, 2007.

- ↑ "Hull House". National Park Service. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ↑ Polikoff, Barbara Garland. With One Bold Act : The Story of Jane Addams, p. 55, New York: Boswell Books, 1999.

- ↑ Johnson, Mary Ann. "Hull House". Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

- ↑ Carroll Smith-Rosenberg. Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in Victorian America. Oxford University Press; 1986. ISBN 978-0-19-504039-5. p. 255.

- ↑ Wade. Louise C. (Winter 1967). "The Heritage from Chicago's Early Settlement Houses". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 60 (4): 411–441, 414. JSTOR 40190170.

- ↑ "Hull-House Maps Its Neighborhood". The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. 2005. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ Christie, C., Gauvreau, M. (2001). A Full-Orbed Christianity: The Protestant Churches and Social Welfare in Canada, 1900-1940 McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, January 19, 2001 pg 107

- ↑ Jane Addams Hull-House Museum

- ↑ Chicago Tribune, May 19, 1890.

- ↑ Jane Addams, Images of Hull House, p. 10.

- ↑ Hamilton, Alice (1943). Exploring the Dangerous Trades – The Autobiography of Alice Hamilton, M.D. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. p. 69.

- ↑ Michael Cordts, "Meet the 'Hull House Kids'", Chicago Sun-Times, Sunday, April 5, 1987, page 6.

- ↑ Polikoff, Barbara Garland. With One Bold Act : The Story of Jane Addams, p. 76, New York: Boswell Books, 1999.

- ↑ Addams, Jane, and Ruth W. Messinger. Twenty Years at Hull-House, p. 72-73, New York: Signet Classics, 1999.

- ↑ Jackson, Shannon. "Theorizing: 'The Scaffolding'." Lines of Activity Performance, Historiography, Hull House Domesticity. Ann Arbor: the University of Michigan Press, 2001 as cited at http://louisville.edu/a-s/english/haymarket/stanton/bibpage.html on March 28, 2007.

- ↑ Polikoff, Barbara Garland. With One Bold Act : The Story of Jane Addams, p. 124-126, New York: Boswell Books, 1999.

- ↑ Polikoff, Barbara Garland. With One Bold Act : The Story of Jane Addams, p. 74, New York: Boswell Books, 1999.

- ↑ Gehl, Paul F. (2004). Grossman, James R.; Keating, Ann Durkin; Reiff, Janice L., eds. "Book Arts". The Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society.

- ↑ Gems, Gerald R. (2004). Grossman, James R.; Keating, Ann Durkin; Reiff, Janice L., eds. "Clubs: Youth Clubs". The Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society.

- ↑ Darling, Sharon S. (2004). Grossman, James R.; Keating, Ann Durkin; Reiff, Janice L., eds. "Arts and Crafts Movement". The Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society.

- ↑ Peggy Glowacki and Julia Hendry, Images of America: Hull-House, Arcadia Publishing, Chicago, Illinois, 2004 p. 34, ISBN 0-7385-3351-3

- ↑ McMillen, Wayne (2007). "SSA Tour: Edith Abbott". The University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration. Archived from the original on December 30, 2006. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- ↑ All ACUA Staff (2007). "Hull House Settlement House Questionnaire, 1893". The Catholic University Of America. Archived from the original on November 30, 2006. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ↑ "Jane Addams' Hull House". City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development, Landmarks Division. 2003. Retrieved January 3, 2007.

- ↑ Sinkevitch, Alice, AIA Guide To Chicago, second edition, A Harcourt Original, 2004, pp. 301-2, ISBN 0-15-222900-0.

- ↑ J. Addams, Twenty Years at Hull House, (New York: MacMillan & Co., 1910), ch.5.

- 1 2 3 "Ghosts of Hull House: Mysteries and Myths. New ebook and podcast!". The Chicago Unbelievable Blog. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ↑ J. Addams, "The Long Road of Woman's Memory," (NewYork, MacMillan & Co., 1917, ch.1

- ↑ "Weird Chicago Blog: The Devil Baby of Hull House". Adam Selzer. 2008.

- 1 2 Christiansen, Richard (2004). Grossman, James R.; Keating, Ann Durkin; Reiff, Janice L., eds. "Theater Companies". The Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society.

- ↑ Haldeman-Julius, Marcet. Jane Addams As I Knew Her (Grand Rapids: Kessinger, LLC, 1999 [1934]), p. 4.

- 1 2 3 "Hull-House Retrospect", Hull-House Bulletin IV, no. 1 (1900), n.p. Urban Experience In Chicago: Hull-House and Its Neighborhoods. 25 Apr. 2006. University of Illinois at Chicago. Fall 2008 <http://www.uic.edu/jaddams/hull/urbanexp/contents.htm>.

- ↑ Telli, Andrea; Richard Pettengill (2004). Grossman, James R.; Keating, Ann Durkin; Reiff, Janice L., eds. "Acting, Ensemble". The Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society.

- ↑ Richard Sisson; Christian K. Zacher; Andrew Robert Lee Cayton. The American Midwest.

- ↑ "Who We Serve". Jane Addams Hull House Association. 2008. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Jane Addams Hull House Museum". University of Illinois at Chicago. Retrieved October 22, 2008.

- ↑ Thayer, Kate (January 19, 2012). "Jane Addams Hull House to close". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Hull House closes after more than 120 years". Fort Wayne News-Sentinel. January 28, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Jane Addams Hull House closing doors". ABC News Chicago website. January 27, 2012. Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- ↑ "Hull House closing Friday". Chicago Tribune website. January 25, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ↑ Webber, Tammy (January 27, 2012). "Hull House Closes Doors After More Than 120 Years". ABC News. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ↑ Mary Hill Swope Papers, University of Illinois Chicago - Richard J. Daley Library Special Collections and University Archives http://www.uic.edu/depts/lib/specialcoll/services/rjd/findingaids/MSwopef.html .

- ↑ "Biographies: Benny Goodman". PBS. Retrieved August 27, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hull House (Chicago). |

- Jane Addams Hull-House Museum

- Jane Addams Hull House Association

- Twenty Years at Hull House, by Jane Addams, New York: The MacMillan Company, 1912 (c.1910) at A Celebration of Women Writers

- Twenty Years at Hull House, by Jane Addams, MacMillan & Co, 1910, at Project Gutenberg

-

Twenty Years at Hull House public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Twenty Years at Hull House public domain audiobook at LibriVox - The Pots of Promise Exhibit

- Urban Experience In Chicago: Hull-House and Its Neighborhoods, 1889-1963

- Hull House Jubilee Article

- Taylor Street Archives: UIC: Flawed History

- Bowen Country Club - digital images from the UIC Library collections

- Hull-House Yearbook - digital images from the UIC Library collections

- Closing of Hull House

- Staff Interview on Closing of Hull House