Huguenot rebellions

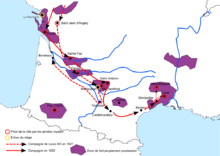

The Huguenot rebellions, sometimes called the Rohan Wars after the Huguenot leader Henri de Rohan, were an event of the 1620s in which French Protestants (Huguenots), mainly located in southwestern France, revolted against royal authority. The uprising occurred a decade following the death of Henry IV, who, himself originally a Huguenot before converting to Catholicism, had protected Protestants through the Edict of Nantes. His successor Louis XIII, under the regency of his Italian Catholic mother Marie de' Medici, became more intolerant of Protestantism. The Huguenots tried to respond by defending themselves, establishing independent political and military structures, establishing diplomatic contacts with foreign powers, and openly revolting against central power. The Huguenot rebellions came after two decades of internal peace under Henry IV, following the intermittent French Wars of Religion of 1562–98.

First Huguenot rebellion (1620–22)

The first Huguenot rebellion was triggered by the re-establishment of Catholic rights in Huguenot Béarn by Louis XIII in 1617, and the military annexation of Béarn to France in 1620, with the occupation of Pau in October 1620. The government was replaced by a French-style parliament in which only Catholics could sit.[1]

Feeling their survival was at stake, the Huguenots gathered in La Rochelle on 25 December 1620. At this Huguenot General Assembly in La Rochelle the decision was taken to forcefully resist the Royal threat, and to establish a "state within the state", with an independent military commandment and independent taxes, under the direction of the Duc de Rohan, an ardent proponent of open conflict with the King.[2] In that period, the Huguenots were very defiant of the Crown, displaying intentions to become independent on the model of the Dutch Republic: "If the citizens, abandoned to their guidance, were threatened in their rights and creeds, they would imitate the Dutch in their resistance to Spain, and defy all the power of the monarchy to reduce them." (Mercure de France)[3]

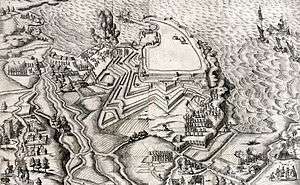

In 1621, Louis XIII moved to eradicate what he considered an open rebellion against his power. He led an army to the south, first succeeding in capturing the Huguenot city of Saumur, and then succeeding in the Siege of Saint-Jean-d'Angély against Rohan's brother Benjamin de Rohan, duc de Soubise on 24 June 1621.[4] A small number of troops attempted to surround La Rochelle under the Count of Soissons in the Blockade of La Rochelle, but Louis XIII then moved south to Montauban, where he exhausted his troops in the Siege of Montauban.

After a lull, combat resumed with numerous atrocities in 1622, with the terrible Siege of Nègrepelisse in which all the population was massacred and the city was burnt to the ground.

In La Rochelle, the fleet of the city under Jean Guiton started to harass royal vessels and bases. The Royal fleet finally met head-to-head with the fleet of La Rochelle in the Naval battle of Saint-Martin-de-Ré on 27 October 1622 in an inconclusive encounter.[5]

Meanwhile, the Treaty of Montpellier was negotiated, putting an end to hostilities. The Huguenot fortresses of Montauban and La Rochelle could be kept, but the fortress of Montpellier had to be dismantled.[6]

The year 1624 saw the arrival of Cardinal Richelieu to power as chief minister, which would mean much harder times ahead for the Protestants.[7]

Second Huguenot rebellion (1625)

Louis XIII did not, however, uphold the terms of the Treaty of Montpellier,[8] sparking renewed Huguenot resentment. Toiras reinforced the fortification of Fort Louis, instead of dismantling it, right under the walls of the Huguenot stronghold of La Rochelle, and as a strong fleet was being prepared in Blavet for the eventuality of a siege of the city.[9] The threat of a future siege on the city of La Rochelle was obvious, both to Soubise and the people of La Rochelle.[10]

In February 1625, Soubise led a second Huguenot revolt against Louis XIII,[11] and, after publishing a manifesto, invaded and occupied the island of Ré, near La Rochelle.[12] From there he sailed up to Brittany where he led a successful attack on the royal fleet in the Battle of Blavet, although he could not take the fort after a three weeks siege. Soubise then returned to Ré with 15 ships and soon occupied the Ile d'Oléron as well, thus giving him command of the Atlantic coast from Nantes to Bordeaux. Through these deeds, he was recognized as the head of the Huguenots, and named himself "Admiral of the Protestant Church".[13] The French Navy on the contrary was now completely depleted, leaving the central government very vulnerable.[14]

The Huguenot city of La Rochelle voted to join Soubise on 8 August 1625. These events would end with the defeat of the fleets of La Rochelle and Soubise, and the full Capture of Ré island by September 1625.

After long negotiations, a peace agreement, the Treaty of Paris, was finally signed between the city of La Rochelle and king Louis XIII on 5 February 1626, preserving religious freedom but imposing some guaranties against possible future upheavals: in particular, La Rochelle was prohibited from keeping a naval fleet.[15]

Third Huguenot rebellion (1627–28)

The third and last Huguenot rebellion started with an English military intervention aimed at encouraging an upheaval against the French king. The rebels had received the backing of the English king Charles I, who sent his favourite George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham with a fleet of 80 ships. In June 1627 Buckingham organised a landing on the nearby island of Île de Ré with 6,000 men in order to help the Huguenots, thus starting an Anglo-French War (1627–29), with the objective of controlling the approaches to La Rochelle, and of encouraging the rebellion in the city. Buckingham ultimately ran out of money and support, and his army was weakened by diseases. The English intervention ended with the unsuccessful Siege of Saint-Martin-de-Ré (1627). After a last attack on Saint-Martin they were repulsed with heavy casualties, and left in their ships.[16]

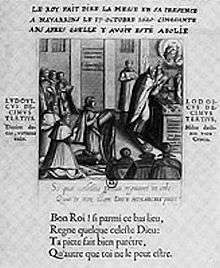

The English intervention was followed by the Siege of La Rochelle.[17] Cardinal Richelieu acted as the commander of the besieging troops (during those times when the King was absent).[18] Residents of La Rochelle resisted for 14 months, under the leadership of the mayor Jean Guiton and with gradually diminishing help from England. During the siege, the population of La Rochelle decreased from 27,000 to 5,000 due to casualties, famine and disease. Surrender was unconditional.

Rohan continued to resist in Southern France, where the forces of Louis XIII continued to intervene in 1629. In the Siege of Privas, the inhabitants were massacred or expelled, and the city was burnt to the ground. Louis XIII finally captures Alès, in the Siege of Alès in June 1629, and Rohan submitted.

By the terms of the Peace of Alais, the Huguenots lost their territorial, political and military rights, but retained the religious freedom granted by the Edict of Nantes. However, they were left at the mercy of the monarchy, unable to resist when the next king, Louis XIV, embarked on active persecution in the 1670s, and finally revoked the Edict of Nantes altogether in 1685.

Aftermath

The Huguenot rebellions were implacably suppressed by the French Crown. As a consequence, the Huguenots lost their political power, and ultimately their religious freedom in the Kingdom of France with the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. These events were one of the factors affecting an unusually strong Absolutist central government in France, which would have a decisive influence on French history over the ensuing centuries.

Notes

- ↑ Fractured Europe, 1600-1721 by David J. Sturdy, p.125

- ↑ Fractured Europe, 1600-1721 by David J. Sturdy, p.125

- ↑ Quoted in The history of France Eyre Evans Crowe, p.454

- ↑ Siege warfare by Christopher Duffy, p.118

- ↑ Huguenot warrior by Jack Alden Clarke p.108

- ↑ Siege warfare by Christopher Duffy, p.118

- ↑ Siege warfare by Christopher Duffy, p.118

- ↑ The history of France Eyre Evans Crowe, p.454

- ↑ The history of France Eyre Evans Crowe, p.454

- ↑ The history of France Eyre Evans Crowe, p.454

- ↑ Dictionary of Battles and Sieges by Tony Jaques p.572

- ↑ The French Wars of Religion, 1562-1629 - Page xiii by Mack P. Holt - History - 2005 p.13

- ↑ Penny cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge Page 268

- ↑ Champlain by Denis Vaugeois, p.22

- ↑ Europe's physician by Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper p.289

- ↑ Siege warfare by Christopher Duffy, p.118

- ↑ Dictionary of Battles and Sieges by Tony Jaques p.572

- ↑ Siege warfare by Christopher Duffy, p.118

References

- Christopher Duffy Siege warfare: the fortress in the early modern world, 1494-1660 Routledge, 1979 ISBN 0-7100-8871-X

- Jack Alden Clarke Huguenot warrior: the life and times of Henri de Rohan, 1579-1638 Springer, 1967 ISBN 90-247-0193-7

- Tony Jaques Dictionary of Battles and Sieges Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007 ISBN 0-313-33538-9

- Mack P. Holt The French wars of religion, 1562-1629 Cambridge University Press, 2005 ISBN 0-521-83872-X